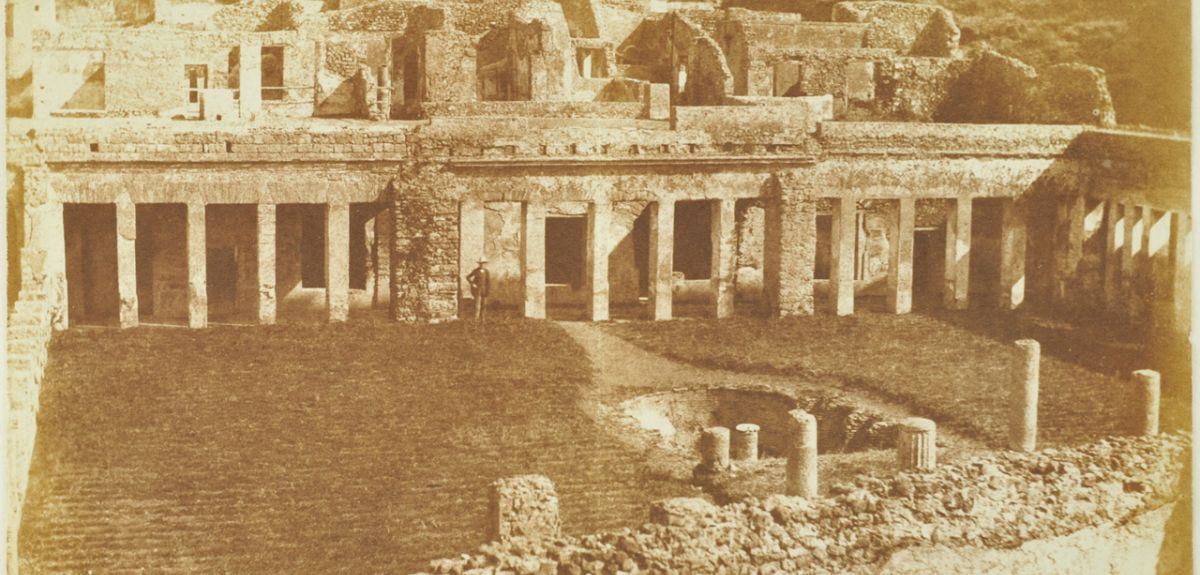

Credit: Fox Talbot Archive, courtesy of Hans P. Kraus Jr.

The Victorian photographer who tried to decipher Assyrian tablets

William Henry Fox Talbot is best-known today as a Victorian pioneer of photography. But an Oxford researcher has revealed that, for Talbot, photography was a means to an end in deciphering some of the oldest writing in human history.

Talbot's "calotype" process is a direct ancestor of modern imaging technology, and his family archive was acquired by the Bodleian Library last year.

"What's not so well-known about Talbot is that he only photographed for about ten years of his life," said Dr Mirjam Brusius, of the Department of the History of Art at Oxford University. "He worked in optics, botany, politics and other areas. In fact, he developed his photographic process in part to help decipher Mesopotamian artefacts.

"He was drawn to what was difficult and obscure. When he worked in botany, he was interested in mosses, because they're very hard to classify and identify. When he first became interested in antiquity, he worked briefly on Egyptian hieroglyphs - but they were too easy, they had already been largely deciphered, so he moved on to Assyrian tablets, and the cuneiform which was not so well understood. Talbot saw the tablets as a kind of mathematical exercise. He wasn't so interested in their content."

Cuneiform is one of the most ancient writing systems to survive in the world, dating back as far as 3000 BC. Knowledge of the system was completely lost until 19th-century Western archaeologists began to uncover clay tablets while excavating in the Middle East.

"Talbot spent a lot of time trying to propagate interest in photography as a tool for archaeological research," said Dr Brusius. "He put in a huge amount of energy but people were happy to use their existing tools, such as drawing. He did his best to convince the British Museum to take a camera on their expeditions, but the chemicals, the heavy equipment and changeable conditions meant they were not keen.

"Even in 1852, ten years after his invention of the calotype, he was still trying to persuade them to use a camera in the museum, to record the artefacts. He was lucky enough to know Lord Rosse [whom we've covered in a previous Arts Blog]. Rosse was a trustee at the British Museum and put in a good word for him, and the museum eventually hired a freelance photographer. The cuneiform collection was photographed, and Talbot hoped to use the resulting images in his research.

"Unfortunately for him, there was a certain amount of rivalry between him and the professional Assyriologists. Talbot was a wealthy gentleman who did not need to work and they considered him an amateur. Henry Rawlinson, a diplomat, was a major figure in the field. He worked out that Talbot was quite good, and didn't want him to be the first to decipher the inscriptions. Rawlinson's Assyriology was essentially a political enterprise, and there were British imperialist interests at play in the Middle East which were somewhat at odds with Talbot's 'armchair science'. So Talbot did not get the photos at first.

"These were inscriptions which could confirm or disprove the historical accuracy of the Bible. Artefacts might be suppressed if they challenged the prevailing narrative: one tablet contained an account of a flood which was at odds with the biblical story. The authority of the Bible as a historical source was seriously contested, and at a time when religious authority was being challenged in a variety of ways by natural science, this was very significant.

"Working in the Talbot archive at the British Library, I found his handwriting on one of the British Museum photographs. It seems that after another nine years, in about the early 1860s, Talbot finally received the photographs. His relationship with the professional Assyriologists gradually improved, along with his reputation and respect, and he was a founding member of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. They had perhaps come to realise that they needed people like Talbot, as much as he needed their contacts and equipment."