Features

This weekend the Thames hosted an historic Boat Race, with the women's crew racing on the same course as the men for the first time. Professor Sally Shuttleworth, a historian at Oxford, leads 'Diseases of Modern Life', a project which explores the medical, literary and cultural responses in the Victorian age to the perceived problems of stress and overwork.

In a guest post for Arts Blog, Professor Shuttleworth compares yesterday's Boat Race to the race of 1863.

With the crowds, the launches, and the world's media watching, the Oxford and Cambridge boat race seems a fairly riotous occasion. Such disruption as we see, however, including Trenton Oldfield's protest in 2012, is as nothing compared to the experience in the mid-nineteenth century.

In 1863, the medical reformer Dr Benjamin Ward Richardson depicted the scenes on the banks of the Thames on the day of the boat race, with maniac equestrians charging through the crowds, cannons firing and blowing off fingers, and even noses: ‘Women screaming from balconies and windows: children falling from garden-walls, or rolling into the stream to be fished out by dogs, half drowned or dead’.

On the river itself, following the rowing boats, were ‘heavy, black, roaring, filibustering steamers, calling themselves “Citizens,” and so weighted with human yelling craft that one side is in the water and the helmsman thinks it a consolation that it could not possibly be a worse fate to go over altogether’.

How sedate we seem now, with our mildly drunken crowds, and carefully managed flotilla of launches, carrying media-men, and a few lucky university members. No lost fingers or noses, no half-drowned children; no black steamers freighted with yelling hordes.

Even the finish, with our excited television announcers proclaiming the results to the world, seems tame by comparison with the Victorian experience: ‘Pandemonium let loose, in such a burst of human throat, cannon throat, steam throat, as charges the very clouds with thunder, and telegraphs to Hercules the news that “Oxford has won”’.

This is the age of the telegraph, but Richardson depicts a wonderful mix of modes of communication: horses instantly dash off in all directions carrying the news, whilst the air is filled with pigeons, ‘ticketed “Oxford has won”’, flying away at sixty miles an hour, and that instrument of modernity, the telegraph, ‘dins every station in the kingdom’ with the news of Oxford’s victory.

Richardson's own interest in this scene of mayhem lies not so much in the spectacle itself, as in its implications for health. The above descriptions come from an article in the newly-founded Social Science Review on the consequences of physical overwork.

The Victorians, as many historians have noted, were deeply concerned about the possibilities of over-pressure on the brain from new modes of work, but less attention has been paid to their concerns with its physical correlate, over-pressure on the body.

Richardson is in favour of exercise, but in moderation. He warns of the dangers of the ‘competitive animal physics’ exhibited in the boat race. His verdict on the triumphant crew is alarming: there is not one 'who will not die so many years sooner by so much effort performed beyond his natural power'. Although extreme in its rhetoric, his argument chimes with current popular and medical concerns about excessive exercise.

In an interesting parallel with contemporary tales of individuals who move from sedentary lifestyles to over-active gym memberships, with fatal results, Richardson recounts the story of men who have ‘waxed fat’ and have joined the Volunteer force (the equivalent of our Territorial Army) "to work themselves down”, and have instead destroyed their health, and worse.

In opposition to the tenets of muscular Christianity, and the supreme faith placed in physical exercise and drill as training for the imperial mission, Richardson suggests that the Volunteer system, 'instead of imparting national strength, … is elaborating national weakness, by enforcing in excess exertion which, in moderation, would be most useful'.

Over the next decades, the Oxford and Cambridge boat race became the focus of repeated medical investigations in an attempt to determine whether placing such a strain on the body did indeed injure health.

Richardson, founder and President of the National Cycling Society, was strongly in favour of exercise, but retained a healthy scepticism towards the benefits derived from the boat race itself: 'Two boats holding crews half naked, said crews tugging might and main to gain a ridiculous staff, opposite and belonging to a “public” house.'

Would he have been surprised to learn that the tradition (with minor modifications) continues unabated to this day?

Diseases of Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives is a five year research project, led by Professor Sally Shuttleworth, and funded by the European Research Council.

An exhibition about the effects of Alzheimer's co-organised by The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) and the O3 Gallery opens in Oxford on Saturday.

'That Other Place' will be shown at the O3 Gallery in Oxford Castle Quarter from 4 to 24 April. The exhibition explores Alzheimer's disease from the perspectives of both sufferer and carer.

The collaboration is part of TORCH’s Humanities and Science series. It follows a TORCH seminar earlier this year, when an interdisciplinary panel of scholars explored the potential opportunities, and challenges, of engagement between the humanities and mental health.

The discussion was led by Professor John Geddes, Head of the Department of Psychiatry at Oxford. Professor Geddes said: 'Deep engagement between humanities and mental health may lead to better treatments. It may also enhance people’s experience of health services and lead to greater public engagement with the challenge of mental illness.'

Highlights of the exhibition include Fausto Podovini’s photographic series MIRELLA, which won the World Press Photo contest in 2013. These images chart the decline of the Mirella’s husband, Luigi, who began to show symptoms of Alzheimer’s aged 65. Mirella cared for Luigi for six years, including during the final year of his life when Luigi no longer recognised his wife.

Hayley Morris's stop-motion film UNDONE, winner of the Slamdance Award 2009, evokes the progressive loss of memory and identity in an Alzheimer’s sufferer.

Stephen Tuck, Director of TORCH, said: 'The Humanities and Science series builds on a longstanding tradition of interdisciplinary work at Oxford, by bringing unexpected disciplines together to address new research questions. One focus of the series has been mental health, which is a growing concern, and one which Oxford is particularly well placed to address.'

'Collaboration with museums and galleries is an integral part of TORCH’s mission,’ says Victoria McGuinness, Business Manager at TORCH. ‘Over the past year we have worked with the Ashmolean, the Museum of Natural History, the Museum of the History of Science and Compton Verney to organise research activity and events that enable exchange between researchers and the public. We are delighted to be staging our first exhibition with the O3 Gallery.'

Helen Statham, Director of the O3 Gallery, said: 'We are delighted to use this opportunity to bring together the artistic and academic life of the city to explore one of the most pressing issues of our time.'

Two new exhibitions have opened at the Ashmolean Museum.

Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray and Great British Drawings will be on display until 21 June and 31 August respectively.

Love Bites marks the 200th anniversary of the death of British caricaturist James Gillray. Visitors can see more than 60 of Gillray’s finest caricatures from the collection of New College, Oxford.

'We are accustomed to seeing caricatures that divide the world along political and personal lines,’ says Professor Todd Porterfield, exhibition curator.

'In this exhibition I hope to emphasise a previously under-explored theme in James Gillray’s work: love, friendship and alliances; and by doing so to provoke fresh insights into his work and to show that Gillray was a substantial figure of his time and an enduringly great artist.'

Great British Drawings showcases the Ashmolean’s collection of British drawings and watercolours, which is considered one of the most important in the world. The exhibition comprises more than 100 words by some of the country’s greatest artists and many of them are on display for the first time.

The exhibition includes work from Flemish artists working in Britain in the sixteenth and seventh centuries and experiments in modernism instigated on the Continent and enthusiastically taken up by the British after the First World War.

'The exhibition of Great British Drawings can only scratch the surface of the extraordinary riches of the Ashmolean’s collections,' says Colin Harrison, Senior Curator of European Art at the Ashmolean Museum.

'It will provide the visitor with an unparalleled opportunity to explore the amazing variety of drawing in Britain, from the rapid sketch in pencil or pen, to the most highly wrought watercolour.'

Ashmolean staff hanging a James Gillray caricature

Ashmolean staff hanging a James Gillray caricatureAshmolean Museum

The remains of Richard III were reinterred at Leicester Cathedral today (26 March 2015).

Dr Alexandra Buckle, an expert in medieval music at Oxford University, has been on the Liturgy Committee for the Reinterment of King Richard III for nearly two years, after finding the only known manuscript to document what a medieval reburial service involved.

Over the last two years, Dr Buckle has been working on the context of medieval reburials, looking at why they happened, who organised them and who received them. She has managed to compile a long list of the great, the good and the not-so-good of the 1400s, involving most kings, dukes and earls.

She said: 'Medieval reburials were far more common than I envisaged. They happened for many reasons – this was an age of active warfare – many who fell in battle were buried cloe to where they fell, only to be moved by family members to a place with family associations 10-30 years later.

'Other reasons include political, status and, always, a desire to keep the dead in the memory of the living. Richard III was involved in two reburial ceremonies (for his father, Richard, duke of York and for Henry VI) so he would have not been unfamiliar with the medieval document of reburial I found, which dates from his life time.'

Dr Buckle's discovery has formed the basis for the ceremony in Leicester Cathedral.

She said: ' The manuscript I found in the British Library has really guided the process: the opening and closing prayers are taken from this, as well as much in between.

'The manuscript includes two unique prayers, not known to survive in any other liturgy, and these have become a real feature of the service. They draw on passages in the bible which feature bones – the famous ‘dry bones’ passage from Ezekiel and the carrying of Joseph’s bones from Egypt to Canaan.

'The document has also influenced the music – although the medieval chant of this service will not be the only music heard, the same items of music will be used. For example, where the document asks for Psalm 150, the chant will not be used but a modern setting of this will be heard instead, in this case a setting, which has been revised for this occasion.

'The manuscript called for a lengthy service, running over two days so some of the material has had to be cut, namely the prayers which draw heavily on the doctrine of Purgatory and are, therefore, not appropriate in a modern, Church of England service. In addition, some modern elements (such as hymns, commissions and The National Anthem) have had to be added to make this service intelligible to the congregation and those watching the broadcast at home but much remains from the medieval rite.'

Dr Buckle said the ceremony gives a dignity to Richard III's memory that would have been missing from his original burial.

'When I started work on this manuscript, I never envisaged it would influence a service of national importance and that some of the prayers I unearthed would end up in the mouth of The Archbishop of Canterbury. The team at Leicester have had a hard task but I think they have managed to blend the medieval and modern sensitively. Richard III’s funeral was notoriously plain and hasty: he did not have a coffin, his grave was too small and he only had the most basic of funerary masses. The overriding concern of the team at Leicester has been to bury Richard, this time around, with dignity and honour, and it has been very special to be involved with this process.'

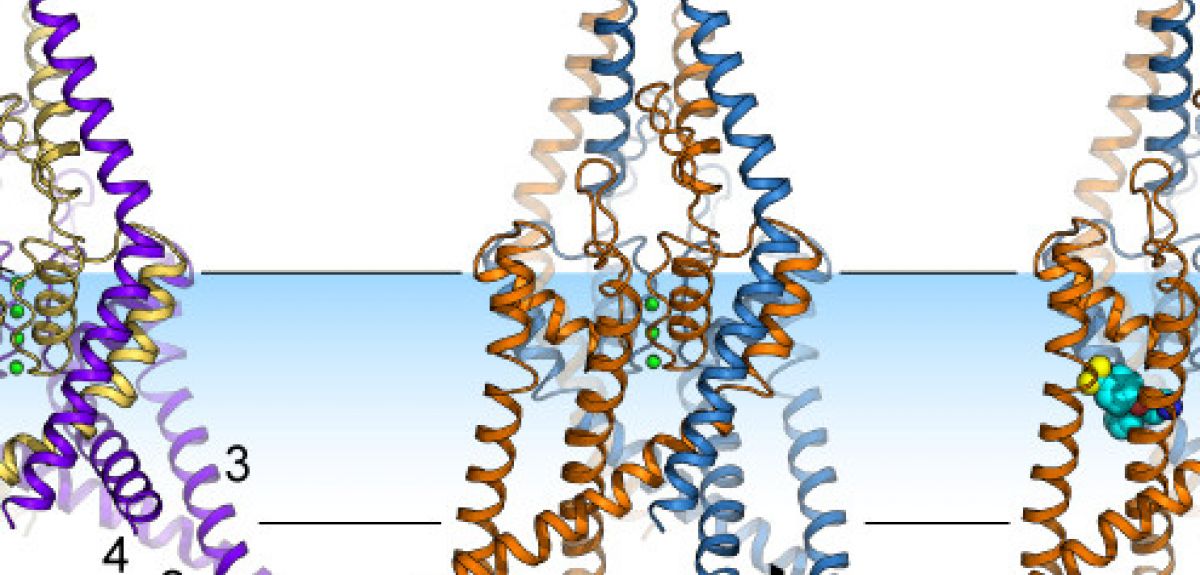

The electrical impulse that powers the workings of the brain and the heart begins with charged particles passing through cellular structures known as ion channels. Using the same technique used to decode the structure of DNA, an Oxford University team has been able to catch snapshots of an ion channel in action. Their results, published in Science earlier this month, help explain how neurons respond to a variety of stimuli, from drugs to touch.

I talked to the lead authors, Professor Liz Carpenter from the Structural Genomics Consortium and Professor Stephen Tucker from the Department of Physics, about why it Oxford is a particularly good place to study ion channels.

OxSciBlog: What are ion channels and why are they important?

Stephen Tucker: Ion channels are literally holes in the cell membrane, and they allow electrically charged particles ('ions') to move from one side of the cell membrane to the other. This is the process responsible for conducting the electrical signal via which the brain and the heart work.

So ion channels are important because they control neuron excitability, which in turn controls how different parts of our bodies talk to each other and how we sense the external world.

Liz Carpenter: Cell membranes are what separate the inside of cells from the outside, and ion channels sit right in the cell membrane. When a nerve fires a burst of electricity, charged particles flow through ion channels, acting like a current. This current then triggers other channel opening, and this is how electrical activity flows down the nerve cell.

OSB: You've got many collaborators from pharmaceutical companies as well: why are these cellular structures of particular interest for people interested in drug development?ST: They're many, many different kinds of ion channels, letting in different kinds of charged particles. We're specifically looking at an ion channel called TREK-2 that let in charged potassium ions, and while you find these channels all over the heart and the brain, they're especially concentrated in nerves that sense pain.

And if we can figure out a way to activate these channels, to keep them open, then we can actually silence the cascade of electrical activity through which neurons communicate. This could potentially block the pain signal from getting to the brain.

OSB: So how are these channels activated?

LC: Originally, people thought that these channels just let in charged potassium ions. But since then, researchers have found that they are activated by stretching the cell membrane, by temperature changes, and by a whole range of pharmaceutical compounds. We still don't know how all these ways of modifying the activity of these channels affects the activity of cells in the brain. What we do know is that in a test-tube, you add some drugs to these channels and they open, and other drugs make them close.

The problem was that before our study, the picture that we had for these ion channels was a little square blob: we didn't actually know what their structure looks like, or how they open and close.

So my group has been studying all possible human ion channels (they are 240 of them!). These proteins are very difficult to crystallize (which you need to do in order to study their structure), but the family of ion channels that TREK-2 belongs to are particularly well-behaved. Not only did we manage to crystallize the TREK-2 channel, but just by chance, we actually got crystals of two different states of the channel: we saw a structure that was stretched, and then another structure that was much less stretched.

OSB: What does the structure of these TREK-2 channels look like?

LC: This channel has two protein chains, with each chain made up of a few thousand atoms. Each chain folds up into a series of helices and loops, which come together to form a folded structure with a pore at the centre. This pore acts as a filter: the oxygen atoms in the pore are lined up in such a way that they can only bind potassium ions, so that is the only thing that can pass through these channels.

When we looked at the crystal structure of these ion channels, we found that the helices could either move down into the inside of the cell, or move up, into the cell membrane. This movement is somehow controlling the flow of ions past the oxygen atoms and through these channels.

OSB: How did you discover this structure?

LC: We have to start by persuading a 'reporter' line of insect cells to produce the protein that we're interested in studying: we splice the gene for the specific protein that we're interested in into an insect virus, which then infects the cells, causing them to make large amounts of the protein.

The next problem we have is that these ion channel proteins are water-repellent (hydrophobic) where they interact with the cell membrane, and water-attracting (hydrophilic) where the interact with the inside and outside of the cells. So we can't just pull these ion channels out of their cell membranes by dissolving them in water.

So we add detergent, which is good at dissolving hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecules: it's not quite washing up liquid that we’re using, but it's not far off!

Then we try use a variety of different reagents to try and persuade all these ion channels to line up in orderly arrays next to each other: to make crystals, in other words. Whether this works or not is very much a matter of luck, I'm afraid!

OSB: Why do you need to crystallize these molecules in order to study them?

LC: We work out the structure of molecules from the diffraction pattern that are produced by passing a beam of X-rays (at the Diamond light source in Harwell) through the material: single molecules by themselves aren't big enough to produce a strong enough diffraction pattern that we can study.

But if we line up each of the molecules to make a crystal, the crystal acts as an amplifier, producing a clear diffraction pattern. We rotated the crystal within the X-ray beam to get different diffraction patterns, and then we worked back from the diffraction patterns to figure out where each individual atom sits in the ion channel.

This is the same technique that was used to work out the structure of DNA, another complex protein molecule. But we're finally getting to the point that we can use this method to look at the structure of human proteins, which have been particularly hard to work with: they’re hard to express in reporter cell lines (if we get half a milligram of protein, we’re very happy!), and hard to crystallize.

OSB: What was the next step, once you had the structure worked out?

ST: We were lucky enough to solve more than one protein structure. But we still didn't know which structure corresponded to the open version of the channel and which to the closed version: just looking at two structures, you can't tell which one was open and which was closed, since it looked like ions could get through both forms of the channel.

So we took advantage of the fact that some drugs, such as Prozac, are known to only bind to the TREK-2 channel when it is closed. So when Liz managed to get a crystal of TREK-2 with Prozac bound to it, we knew that this version of TREK-2 had its 'pore' closed, not allowing potassium to travel through it.

LC: We also wanted to track exactly where Prozac binds to the channel. But Prozac itself doesn't show up in the diffraction patterns that we're using, so we used another trick: we attached a molecule of Bromine to the Prozac. Bromine lights up nicely in the diffraction pattern, and lets us see exactly where the Prozac is attaching itself to TREK-2.

So we really needed all sorts of different expertise in order to these experiments: my experience is in decoding protein structures, and Stephen's interest is ion channel function. But we needed the help of our colleagues from the Chemistry Department to do the Bromine tagging experiment, and colleagues at a pharmaceutical company supplied us with the drugs that we used in the experiment.

ST: In Oxford, we're lucky enough to have a huge consortium of people who work on ion channels (the OXION consortium), and I think this study demonstrates why Oxford has become a major international centre for this kind of work. For example, the two images that we got were frozen snapshots, but we think that this channel is likely to exist in many states, rather than just two. Computational modelling from other colleagues (Professor Mark Sansom in the Department of Biochemistry) was also essential to give us an idea of how the protein might actually move in a cell membrane.

OSB: What sort of future work are you planning?

ST: The drug that we looked at, Prozac, binds to a 'window' in the channel that only exists in its closed state. We'd like to look at how some other drugs bind to TREK-2, and we need very high-resolution 'pictures' of the channel in order to do this.

LC: There are other ion channels related to TREK-2 that we'd like to look at: one of them, TRESK, has been linked to migraines for example. We'd like to work out the structure of these channels, especially since many of them have been linked genetically to diseases. We're also trying to get more uniform crystals to increase the resolution of the structure we get.

We're also going to use a fantastic new device called the LINAC Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in Stanford: it is about a billion times more powerful that the light source we've used previously, which means that laser pulses hit the sample hundreds of times every second. What we're going to do here is fire a slurry of small crystals through the LCLS beam. The crystals explode as they hit the beam, but we get our data before the atoms within the crystal have time to move apart. The data we get from the LCLS is going to much higher-resolution, and it will allow us to study ion channels that don’t crystallize into large crystals.

- ‹ previous

- 152 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria