Features

One of the most popular Arts Blog posts this year was a reproduction of the speeches by Marcus du Sautoy and Ben Okri at the launch of the Humanities and Science series at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Since then, there has been an exciting series of events featuring Oxford academics from backgrounds of both arts and sciences.

And this week, TORCH has announced a collaboration with the Science Museum in London to offer a Research Fellowship for an Oxford academic to carry out research on the Museum's collections.

The chosen fellow will contribute to the Museum’s forthcoming exhibition programme, which includes exhibitions on ‘The Wounded’, which marks the centenary of the First World War, and ‘Mathematics’, which tells the stories of mathematicians, their tools and ideas from the 17th century to the present. The fellowship will facilitate exchange by bringing Oxford academics into the Science Museum, and the Museum collection feeding back into the individual’s research.

'Research plays a vital role in deepening understanding of our collections, developing new approaches to our work, and in reaching new audiences,' says Dr Tim Boon, Head of Research & Public History at the Museum. 'We are delighted to be working with TORCH on this new fellowship, which will bring new perspectives to our collections.'

The Science Museum's new Research Centre opens in Autumn 2015 and fellows will be able in 2016 to take advantage of the facilities to consult the collections, library and archival material. Fellows will also be given dedicated space within the centre for their research.

The Humanities and Science series continues apace with three events this week. For more information, keep an eye on the TORCH website.

Social media, the Ebola epidemic, and World War I are just some of the things that have influenced British children's creativity and use of language over the last year, according a report published today by Oxford University Press (OUP).

OUP's analysis of 120,000 short stories that children submitted to the BBC's 500 WORDS competition 2015 revealed a wealth of fascinating insights into the lives of British children and the imaginative ways in which they use English.

Hashtag – and the symbol used to represent it '#' – is unmistakeably the 'Children's Word of the Year', due to its significant shift in usage by children writing in this year's competition.

The symbol is entering children's vocabulary in a new way, as they have extended the use from a simple prefix or a search term on Twitter, to a device for adding a comment in their stories.

The rise of mobile technology and social media is the predominant theme for 2015. Of the top 20 words which have significantly increased in use during the past 12 months, over half are inspired by youngsters' understanding and use of social media – youtube, Zoella, snapchat, selfie, vlog, blog, Instagram, emoji, and Whatsapp.

Young authors also demonstrate a keen interest in the world around them. International current affairs, particularly the more harrowing situations, are reflected in their stories. Ukraine, Syria, Malaysia Airlines, and peacekeepers all feature. However, one global event dominates over all others – the Ebola crisis in countries such as Sierra Leone and Guinea.

Events to mark the centenary of World War I have clearly had a big impact on children. Many historical and contemporary stories hone in on specific events surrounding the Great War, such as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and, for this year, the sinking of the Lusitania (1915).

500 WORDS is the BBC Radio 2 Breakfast Show's short story writing competition for children aged 13 and under. Children were invited to compose an original work of fiction, using no more than 500 words.

OUP's analysis of the submissions was powered by the Oxford Children's Corpus – a large electronic database of real and authentic children’s language – the only one of its kind in the world. It is used by lexicographers and linguists as part of OUP's on-going language research and dictionary compilation programme.

Vineeta Gupta, Head of Children's Dictionaries at Oxford University Press said: 'Language is constantly changing and adapting. Children are true innovators and are using the language of social media to produce some incredibly creative writing. What impresses me most is how children will blend, borrow, and invent words to powerful effect and so enrich their stories.'

When oaks burst into life in spring populations of oak-leaf-eating caterpillars boom: this offers a food bonanza for caterpillar-munching birds looking to raise a family.

But, if you’re a bird, how do you time your breeding to exploit this seasonal food source? Understanding this is essential if scientists are to predict which species will be able to adapt to spring arriving earlier due to climate change.

Amy Hinks, Ella Cole, and Ben Sheldon, of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, looked into this question by studying great tits at Wytham Woods which feed on winter moth caterpillars which, in turn, feed on the newly-emerged leaves of oak trees.

The team monitored the bud development of all oak trees and the timing of egg laying of all great tits across 28-hectares of deciduous woodland. They also measured caterpillar abundance at a sample of oaks throughout spring.

The team report in American Naturalist that the timing of leaf emergence of a given oak is a reliable predictor of when caterpillars are most abundant on its foliage. However, individual oaks have their own sense of timing: when each tree buds is consistent over many years and does not tend to follow average temperature trends.

'We found that the laying date is best predicted by the timing of oak leaf emergence within the immediate vicinity, less than a 50 metre radius, of the nest,' said report author Ella Cole of Oxford's Edward Grey Institute.

'There is evidence to suggest that great tits use large-scale cues such as temperature and day length to time their breeding. The results from this study show that temperature cannot be the whole story: in addition to using these global cues, tits are able to fine-tune their breeding decisions based on information from their local environment.

'It is thought that female tits may be using information on the presence of early-stage caterpillars or the stage of development of tree buds. In early spring tits can be seen closely inspecting, and sometimes even eating, tree buds which may be how they collect this information.'

Although there is evidence from other bird species that vegetation cues are used to time egg laying, experiments on captive great tits that have tried to test this – by providing birds with either leafing or non-leafing branches – have been unable to influence laying date.

'However, as these experiments were done in captivity, it is not clear how much they reflect what birds do in the wild,' Ella tells me. 'Precisely what cues birds are using to synchronise their breeding cycle with their immediate environment remains a bit of a mystery, and we clearly need further work exploring this question.'

Away from the imposing skeletons of dinosaurs and whales and the famous Oxford Dodo the Oxford University Museum of Natural History is home to miniature treasures.

These include the jewel-like bodies of bugs in the Hope Entomological Collections, which feature over 25,000 arthropod types. Pull out one of the drawers displaying a fraction of the five million specimens and you’ll be dazzled: despite many of the specimens having been collected in the 19th Century they still shine with vivid colours.

So why don’t the bright blue and green colours of these bugs fade?

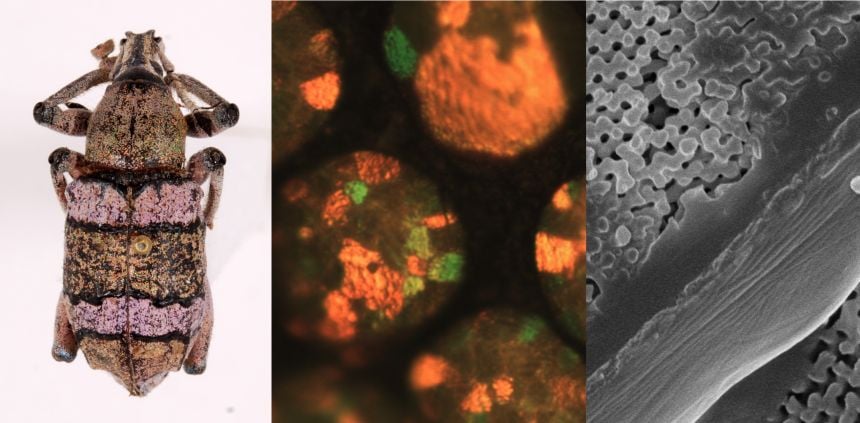

Recent work led by Oxford University and Yale researchers reported in Nano Letters explores how, instead of using perishable pigments, arthropods have evolved ways to create ‘structural colours’ by using tiny structures (100-350 nanometres) that scatter light.

'The most common method to produce vivid and saturated structural colours in insects is using a multilayer or thin-film (like an oil-slick) nanostructure which produces iridescence. Typically, this is formed over the entire surface of the insect, especially the thorax and abdomen (and elytron in the case of beetles),' explains lead author Vinod Saranathan, who undertook the research at Oxford University's Department of Zoology before taking up a new role at the Yale-NUS College in Life Science, Singapore, later this year.

Vinod led the team, which used high energy synchrotron X-rays to examine colour-producing or photonic nanostructures in around 127 species of beetles, weevils, bees, and spiders. They found that diverse groups of these arthropods have independently evolved light-producing or biophotonic nanostructures that are the exact analogues of the complex shapes seen for example, in blends of block-copolymers (large molecules similar to Lego building blocks, having both hydrophilic and hydrophobic ends), but at ten times the sizes usually seen in these synthetic chemical systems.

X-rays reveal the nanostructures the create structural colours

X-rays reveal the nanostructures the create structural coloursHe tells me that OUMNH's Hope collections were vital as: 'a 'one-stop shop' to survey insects and arthropods for structural colour. These historical collections are not only invaluable for my research because of their sheer number (second only to NHM in London) but many of the insects are conveniently organised by the collectors and provide a representative sample of the diversity of insects and other land arthropods. They also have an amazing and growing collection of tarantulas from around the world thanks to Ray Gabriel.'

Whilst, over millions of years, many groups of bugs have evolved to harness structural colours, different arthropod families have come up with their own unique solutions:

'We found in this study that some butterflies, weevils, longhorn beetles, bees, spiders and tarantulas have a very fine covering of scales or hair-like setae (like shingles on a roof) covering the entire surface of the arthropod and these scales (roughly 50-100 microns across) contain a wide variety of colour-producing or photonic nanostructures, from nano-cylinders, -spheres, perforated multi-layers, and complex maze-like, 3D structures such as single gyroid, single diamond, and simple cubic networks,' Vinod tells me. 'However, a given family of insects have evolved to use only one particular type of nanostructure to make colour.

'Despite their diversity, all these photonic nanostructures work on the principle of light interference – as these nanostructures are on the order of visible wavelengths of light, wavelengths that match this periodicity are reinforced and reflected back as the observed colour.'

You might think that these complex nanostructures are confined to complex animals but, Vinod explains, they appear to be innate in the living cells of animals and plants and some of them can be found within the membranes of mitochondria or chloroplasts (they just don’t play a role in making colours): 'Insects and spiders appear to have evolutionarily co-opted this innate ability of cellular membranes to sculpt complex shapes within the cell to make a colour.'

But these nanostructures aren't just of interest to those studying arthropods. Scientists and engineers currently find it very challenging to replicate such complex shapes using chemical polymers at optical length scales and Vinod believes we could learn a lot from colourful arthropods:

'Insects and spiders have been effectively manufacturing these biophotonic nanostructures for millions of years, so we should look to nature to either mimic the same developmental process that gives rise to these nanostructures or use them as direct templates for new photonic technologies and sensors.'

Martin Parr, the renowned documentary photographer, visited the Oxford University Museum of Natural History recently to mark its nomination for The Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year 2015.

One of his images (above) shows children in a primary school workshop getting their hands on a real dinosaur egg.

He was taken around the exhibits by Scott Billings, public engagement officer at the Museum. A photographer himself, Scott snapped a photograph-of-Martin-Parr-taking-a-photograph (above).

He says: 'Having a Magnum photographer visit the Museum for a photoshoot isn’t something that happens every day, so it was a real privilege to take Martin Parr around the building – in the public areas and behind the scenes – and watch the types of things that caught his eye.

'I am a keen photographer myself, with an interest in the history of photography as an art form. I have a few books of Martin Parr’s work, so it was especially exciting to not only meet Martin and watch him work, but also to photograph the process myself too.

'Anyone familiar with Martin Parr's work will know that his speciality is picking out the behaviours, styles and environments that describe not how we would necessarily like to see ourselves but how we are.

'Subjecting the Museum to the same scrutiny was a little daunting, but Martin captured a combination of images, some with his typical forensic observation and others sympathetic to the beauty of the building and its collections.'

The Art Fund is currently running a photography competition for each of the six nominated museums, asking people to send in their best photograph of one of the museums. Martin Parr will help shortlist six photographers – one for each museum – and then a public vote will decide the winner.

Amateur photographers (or even just smartphone owners!) can upload their photo by Sunday 31 May or Tweet or Instagram it with the hashtag #motyphoto and tag @morethanadodo.

- ‹ previous

- 150 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?