Features

The Oxford Changing Character of War Programme, based at Pembroke College, is devoted to the interdisciplinary study of war and armed conflict.

Its co-director, Oxford historian Dr Rob Johnson, says the attacks on Paris by so-called IS militants are a clear example of how the character war has changed. In the following article, he outlines the strategic options open to other countries.

In his declaration that "France is at war", the French president, François Hollande, noted that this could not be a war between civilisations because the Islamic State (IS) movement does not represent a civilisation.

In essence, IS is barbarism. It subverts the Western laws of armed conflict, the ethics of war and international humanitarian law.

It attacks while concealed by the population, does not adhere to the truth in its information operations and has declared that it will mount mass casualty attacks on those who do not conform to its ideas.

Its treatment of prisoners is on a par with the worst atrocities of Nazism and it has no interest in the Western priority of protecting civilians.

The group's recent attacks in Paris show that the character of war has changed and that, therefore, so must our response – as unpalatable as that may be. Beyond the initial sadness and anger, a longer-term strategic approach is needed.

Hollande made it very clear that he believes France, and by extension the rest of the world, is “at war” with terrorists.

There were plenty of critics who argued after 9/11 that the idea of “War on Terror” was a misnomer, as it’s not possible for a state to wage war on a tactic - and the Bush administration indeed struggled to apply the label of war to the processes of guarding against, deterring, detecting and pursuing terrorists.

But the situation now is different. The scale of the attack in Paris and the prospect of repeated attacks on France and French interests fulfils the criteria of an act of war – and similarly, the passionate indignation of the French people and the desire to respond with some gesture or counterstroke has the hallmarks of war.

In the 20th century, Europeans started on a path to try to prevent war by the use of conventions, principles and legal instruments.

After the breakdown of diplomacy between the major powers led to a catastrophic global war in 1914-18, there were efforts to secure global diplomacy by enshrining it in an institution – first the League of Nations and then, after World War II, the United Nations.

The UN is starting to address the actions of terrorists through its Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force (CTITF), but it is revealing that this massive global instrument for dealing with wars between states is foundering when its members are violently confronted by smaller, non-state entities.

Describing IS as a “state” is just as erroneous as misjudging a state’s response to a terrorist organisation. What is required is a careful calibration of policy based on a clear understanding of the character of the war one is confronted with, and the nature of the adversary.

What’s the plan?

The US president, Barack Obama, admitted in the summer of 2015 that his government had "no complete strategy" for defeating IS, in part because it was keen not to be dragged into another Middle Eastern conflict where American interests were not threatened directly.

There was talk of “containment” and airstrikes by manned and unmanned aircraft. Critics pointed out that the goal was unclear.

Hollande has been more specific. His aim is to destroy IS forces so they cannot attack again. The US has reiterated that its ambition is the annihilation of IS as well.

Diplomats have been willing to point out that the military instrument should be used in conjunction with other tools, but they also emphasise again the need for a set of defined ends.

If IS was to be crushed in Syria, what, in fact, would replace it? Whose government and troops would control the space IS occupied? And who would pay for it all?

Sun Tzu advised in the Art of War that one must defeat the enemy’s strategy, rather than his military forces. The trouble with IS is that its strategy is dichotomous. It wants to establish a caliphate, but it also wants to wage war for the sake of it.

What is not not yet clear is whether IS has opened a new front in Europe because it is under intense pressure in Syria and Iraq, or whether it is expanding its strategy because of its successes.

A silver lining

A belligerent state’s interests can be identified, and states tend to be constrained by the rules of statehood, such as economic exchange and diplomatic relations. IS, like al-Qaeda, is not governed by such constraints – and there are few corresponding shared interests.

To defeat the group’s strategy therefore means denying IS is a state. But the more complex goal – preventing IS from waging an indefinite war for the sake of it – is more long-term. That demands a calibrated military effort.

France and its Western allies are labouring under various constraints. They cannot appeal to decency, restraint or rules, as IS is already waging war in contravention of established norms.

They cannot deter, since deterrence only works if an enemy is willing to be deterred through weakness or concern for losses. There are, however, strategic opportunities.

There is plenty of evidence to show that the group lacks popular support across the Muslim world. There needs to be a concerted campaign to cut off what international support it does have through a diplomatic offensive.

Historically there are precedents, such as the demise of the communist campaign against Oman in the 1970s which, when terrorist financing was suddenly severed and the movement’s leaders discredited, led to its collapse.

More important still, the attacks on France have given major states a common cause – and that is the greatest opportunity of all.

Dr Johnson originally wrote this article in The Conservation.

It sounds like – and is – a light-hearted way for DPhil students to share their research with the world. But for Merritt Moore, the international Dance Your PhD contest offered the opportunity to combine two passions and prove that the arts and sciences are not mutually exclusive.

Merritt, a professional ballet dancer who is carrying out a DPhil in atomic and laser physics at Oxford University, won the physics category of the competition, organised each year by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Merritt said: 'When I first found out I'd won, I was excited – this contest is meant as a light-hearted way to let people share their PhDs, but for me it also highlights an issue that I've been pushing against for most of my life.

'I've constantly been told that I can’t pursue my two passions at the same time, but I've worked hard to prove that wrong by continuing both physics and dance. I've danced professionally with Zurich Ballet, Boston Ballet and English National Ballet while graduating in physics at Harvard and pursuing a PhD in atomic and laser physics at Oxford.

'This contest gave me the chance to overlap the two in a way that I rarely get to do, so winning the physics category is just a bonus!'

Merritt's DPhil research involves creating pairs of photons to be used for quantum information experiments. A photon is a particle of light, and by creating controlled pairs of them, scientists can explore exotic and fascinating properties of quantum mechanics, such as entanglement.

Describing her award-winning dance, titled 'EnTANGOed', Merritt said: 'In order to describe how we create pairs of photons through the dance, a powerful laser (represented by the pianist’s hands driving the music) is guided into a non-linear crystal (the laboratory). When the laser interacts with the crystal, pairs of photons (the dancers) are generated – a process known as spontaneous parametric down-conversion.

'The generated photons have half the energy of a laser photon to satisfy energy conservation (hence the lower "red frequency" dress and tie). Even when a photon pair leaves the crystal (the lab), they continue down the same path. It is only when they are separated by a polarizing beam-splitter that the two photons are forced in different directions, because of their different polarizations.

'These photons are generated spontaneously and would otherwise be impossible to measure without destroying them, therefore they are intentionally separated so that one can be detected to herald the existence of the other. We can use the remaining photon as a carrier of quantum information for our various applications.'

1st December each year marks World Aids Day: an opportunity for people worldwide to unite in the fight against HIV, and remember the over 35 million people who have died of HIV or AIDS. This death toll makes AIDS one of the most destructive pandemics in history, and an estimated 37 million people (including over 100,000 in the UK) live with the virus.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) leads to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition where the body’s immune system increasingly begins to fail, leading to life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers. Without treatment, the average survival time after HIV infection is estimated to be 9 to 11 years. Researchers at Oxford University have led the fight against HIV/AIDS for many years, from tracking where the global spread of HIV first began, to leading trials of potential HIV cures.

The Oxford Science Blog caught up with one such researcher, Professor Lucy Dorrell, a scientist and a clinician at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, to ask how her work aims to defeat AIDS.

OxSciBlog: How has the treatment for HIV/AIDS changed over the years?

Lucy Dorrell: I started working with AIDS patients in London in the early 1990s, and back then, we had no effective treatments – all we could offer was palliative care. We had a ward with sick patients, and we tried to make the end of their lives as comfortable as possible. But a few years later, the same ward was practically empty: while we still occasionally get patients where HIV has been diagnosed at quite a late stage, when the patients are already very, very sick, HID/AIDS treatment has been completely transformed.

The main determinants of health for HIV patients are the same as for everybody else: not smoking, eating a healthy diet, exercising, etc. This is a very different message from the early years!

What brought about this transformation is the finding that the HIV virus can be completely blocked from replicating and making more copies of itself, by using a combination of antiretroviral drugs. This allows the immune system to recover, and people then don't get AIDS, even though they still have HIV in their body. It took a while to develop an effective treatment: while the basic finding was uncovered in 1996, the early drugs were really quite unpleasant: they had a lot of side-effects, and people had to take lots of pills each day.

Now, the majority of people just need to take one or two pills a day, and they will be fine – I spend a lot of time as a medical doctor telling patients that they will have a near-normal life span if they take their treatment every day. Instead, the main determinants of health for HIV patients are the same as for everybody else: not smoking, eating a healthy diet, exercising, etc. This is a very different message from the early years!

OSB: How do these drugs work?

LD: Antiretroviral drugs target the key enzymes that HIV uses to make DNA copies of its RNA and to produce the proteins that are then assembled into new viruses. Newer drugs are available that block the virus from inserting the DNA copies it has made into the host cell chromosomes.

The problem with this treatment is that people have to take it for the rest of their lives: it doesn't provide a cure. Once HIV gets into the body, it infects a subset of white blood cells, CD4 T cells, a really key part of the immune system. Once a cell is infected, it might be killed straight away, but it might also start generating new copies of HIV. But most often, HIV just goes into a cell and hides in a dormant form.

This is a big problem, because these cells, carrying HIV's genetic material, can survive in the body for a long time. If that cell is activated – say, by signals to the immune system such as contact with another infection- it will start making new copies of the virus. These new copies then go on to infect more cells, and the cycle repeats. The drugs that we currently have can't clear the body of this form of non-replicating HIV, since they work by targeting enzymes involved in HIV replication.

This dormant form of HIV is invisible to the body’s own immune system.

What is more, this dormant form of HIV is invisible to the body’s own immune system as well: the immune system detects and destroys infected cells by looking for virus-produced proteins on the cell surface. But if the virus is not replicating, it is not making any proteins.

The one silver lining is that in this dormant form, the virus is much less infectious, and therefore much less likely to be passed on. This is another part of the success story of antiretroviral drugs; they not only stop people dying, but they stop the infection being passed on to other people. This is part of the reason that number of new HIV infections is going down globally.

OSB: What is the alternative approach that your research takes?

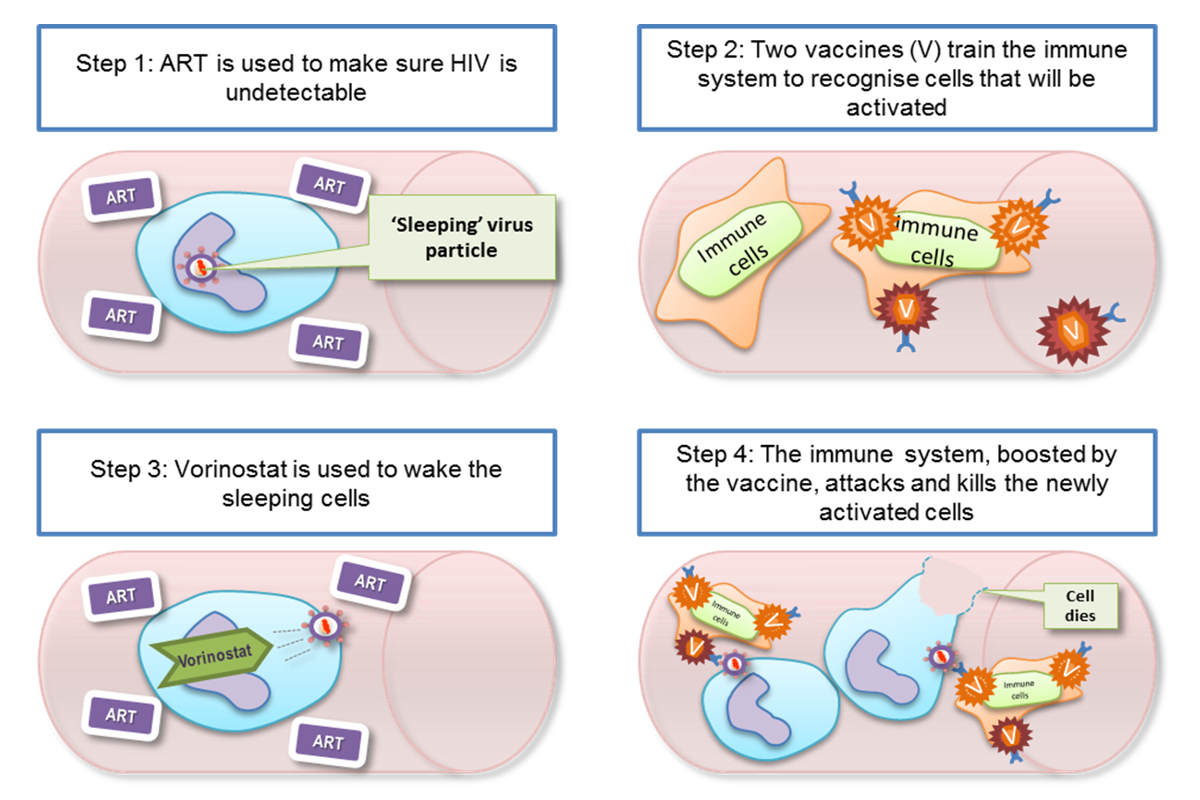

LD: We want to find an alternative to having people take drugs for the rest of their life. We are trying to find ways to get the body's own immune system to fight HIV better, and fully remove it from the blood stream. We’re working on getting the immune system to ‘see’ infected cells better so that they can be targeted for removal. Combining this kind of immune-based strategy with a drug treatment is one way to eradicate the population of long-lived cells which are harbouring the dormant virus. If this treatment works, then we hope that one day, people infected with HIV will not have to take drugs for the rest of their lives.

What currently looks likely to work best is a combination of two different strategies: first, finding a way to reveal the dormant virus hiding in infected cells, reactivating it very carefully so that the virus then doesn’t spread to other cells. Second, to beef up the body's natural immune response, so that when infected cells are woken up, the immune system kills these cells straight away.

This strategy capitalizes on the fact that the immune system does put up a good fight against HIV, even without any treatment. It is just that HIV is a step ahead, because it is able to mutate so quickly: the body might be able to generate an effective immune response to one particular HIV protein segment, but if the virus mutates in that region, then that immune response stops being effective. This happens again and again, right from the moment HIV first gets into the body, stopping only when we give the treatment that stops HIV making more copies of itself. At this later stage, the immune system isn't very effective at fighting HIV at all.

OSB: How do you put this approach into practice in the clinic?

LD: We're working on the second strategy, of making the immune system more effective at fighting HIV.

We've been trying to understand why the natural immune response is not effective enough, and what it needs to do in order to be effective. One of the things that we have been working on is ways of defining what constitutes an effective immune response, and what we eventually want to do is make a vaccine.

There is no one in the world who, once infected, has been able to clear the virus from their body with no external treatment.

This is particularly difficult, because unlike many other diseases, there are no naturally-occurring examples of an immune system that has successfully fought off HIV completely: there is no one in the world who, once infected, has been able to clear the virus from their body with no external treatment. The only person to ever have been cured of HIV/AIDS is an American called Timothy Ray Brown, who received a bone marrow (stem cell) transplant for Leukaemia while he was HIV positive. The bone marrow donor had a two copies of a gene that confers resistance to HIV: people with both copies cannot be infected with most HIV strains, but unfortunately this is very rare – roughly 1% of people with European ancestry have this variation, and it is even rarer elsewhere.

The bone marrow transplant meant that Timothy essentially got a new immune system – one which couldn't be infected with HIV!

Bone marrow transplantation carries a lot of risks, so this can't be the standard treatment. But people are beginning to use personalized genetic engineering to do something similar.

The problem with this approach is that it is difficult to scale it up to treat millions of people, and the fact that there are no naturally occurring examples of someone successfully clearing HIV from their body means we can't learn from nature when it comes to AIDS. So we're having to approach this in a completely different way.

OSB: Are there natural variations in HIV immune responses that you can exploit?

There are very rare (less than 1% of the HIV-infected population) individuals who are called long-term non-progressors: they have undetectable levels of the virus in their blood, so their diagnostics look like they are being treated with antiretroviral drugs, even when they have had no treatment at all.

LD: There are very rare (less than 1% of the HIV-infected population) individuals who are called long-term non-progressors: they have undetectable levels of the virus in their blood, so that their diagnostics actually look like they are being treated with antiretroviral drugs, even when they have had no treatment at all! These individuals remain healthy and somehow seem to be able to keep the virus at a very low level for a long period of time, without any treatment.

We and many other groups have been studying this group of patients for a long time, to try and work out what is different about their immune response. We’ve learnt that a lot of this naturally-occurring resistance has to do with the genes coding parts of the immune response to virus-infected cells. But that is not the whole story, and in our lab, we've been studying how specialized immune cells from these patients deal with replicating HIV in a culture. We've developed a test that mimics, as much as possible, what we think is going on in a real immune response in the body.

What this line of work has shown is that long-term non-progressors are at one end of a spectrum, and while it seemed that they may be in a special class all by themselves, there are others who share some of their characteristics but to a lesser extent. There was a feeling that this was really the only group of patients worth studying, but we've shown, by carefully measuring immune responses from a variety of patients in the lab, that an effective immune response is not an all-or-nothing property.

The big question now is whether we can nudge someone on one end of the spectrum of immune responses to the other, so that they are able to fight of the virus better.

OSB: How are some people able to fight HIV better?

LD: Looking at the naturally occurring variation in immune system responses, it is clear that what happens when the immune system first confronts the virus is very important, so there is a real push to give treatment for HIV as early as possible.

The second key factor to the success of the immune response seems to be where it is targeted: the HIV genome is unstable and changes all the time, which means that the virus can afford to take a lot of hits from the immune system, since their target simply mutates without doing much damage to HIV. But there are part of the HIV genome where the virus cannot afford this strategy, and hitting these more conserved regions really does make it more likely that the virus will be killed.

People who can mount a better immune response against HIV generate more hits against the virus, which makes sense: the more hits the virus takes, the greater the chances that one of them will land in one of these vulnerable regions. But rather than having a scattergun approach, these more effective immune responses also seem to be able to generate more well-targeted hits against vulnerable HIV regions.

OSB: How are you trying to nudge the immune system to be more effective?

LD: We're trying to leverage these naturally-occuring strategies to produce a vaccine for people already infected with HIV: we've been carrying out clinical trials with HIV positive patients over the last ten years, and our current trial is on patients who have been given treatment within weeks of being exposed to the virus. We vaccinated 24 of these patients with a vaccine that we've developed in Oxford – the vaccine tries to hit the virus in its most vulnerable parts, where it is least likely to mutate.

This is going to be a long, step-by-step process and we're likely to see small changes to start with, but we can then try and come up with ways of making these into bigger changes!

We’re currently looking at what is happening in these patients' immune systems as a result of this beefing up. We're also tracking what happens to the virus reservoir: the total number of infected cells where the virus is hiding. We're interested in seeing whether this reservoir will change over time – it did not change much with just the antiretroviral therapy combined with vaccination. So the next step will be to actually 'wake up' the virus, and then see what happens to it when this unmasking is combined with the vaccination and the antiretroviral therapy.

We hope that the vaccination will produce plenty of specially primed killer T cells that are ready and waiting to eliminate those long-lived CD4 T cells carrying dormant virus as soon as they are 're-awoken'. If this goes according to plan, then we should see a reduction in the HIV reservoir in the body.

I think this is going to be a long, step-by-step process and we're likely to see small changes to start with, but we can then try and come up with ways of making these into bigger changes!

Dr Zeeshan Akhtar is a Royal College of Surgeons Research Fellow and Scientific Secretary of the COPE Consortium, which aims to advance and develop organ preservation technologies. Here, he writes about his research into how we could ensure more organs are suitable for transplant.

By the time your day is over 10 people in the UK will have been diagnosed with organ failure, a process by which one of their vital organs (used for sustaining life) fails. Their only hope for long term survival is to receive a lifesaving organ transplant. In the UK there are over 6900 people on the waiting list for an organ. Approximately one third of these patients will not receive a transplant. They will either die whilst on the waiting list, or become too unwell to undergo the transplant operation itself. For these patients the waiting list is the most unfair of death sentences.

In the UK there are over 6900 people on the waiting list for an organ.

Transplant not only saves lives but also improves the quality of life for patients. Consider those with kidney failure who are dependent on dialysis, an artificial 'filter' which cleans their blood of waste products. They often have to undergo dialysis 3-4 times a week for 4-5 hours at a time. Holding down jobs, going on holiday and the things many of us take for granted are simply not possible for them. Transplant offers freedom.

The chronic shortage of suitable organs for transplant has been a major challenge for the medical community in the last decade. This is predicted to worsen as the population ages and with chronic diseases such as diabetes on the increase. Health complications associated with obesity and smoking also mean more and more people will have kidney, liver, pancreas, heart and lung failure.

To begin to address this urgent need, doctors are now considering organs that previously would have not been deemed suitable for transplant, including organs from older donors who have had large strokes. The size of their stroke is substantial enough to stop their brain from functioning irreversibly, a process known as brain death. The organs from these older donors sometimes have poorer outcomes, but knowing how these organs will function both immediately after transplant and in the long term remains unknown.

My research focuses on kidney and liver transplantation, with an interest in understanding how organs become injured during the brain death process and determining what can be done to protect and preserve organ function. In addition to this, I aim to develop methods which will allow us to predict the outcomes of transplant using information from the donor, providing doctors with a more definitive risk analysis to help them to decide whether to transplant an organ or not.

We are aiming to develop a type of 'barcode' using these markers, which will in the future help us decide whether an organ should be transplanted or not.

My research has focused on the impact of brain death on the kidney and has indicated that organs from brain dead donors are significantly injured, even before they are removed from the donor for transplant. I have shown in the kidney that mitochondria, the 'powerhouse' of cells, responsible for energy production, are affected by brain death even after relatively short periods of time (up to 4 hours). Consequently cells can no longer produce sufficient energy through the usual means and rely on other, less efficient, pathways for energy production, such as energy production from pathways not involving mitochondria. The damaged mitochondria produce harmful waste products which further damage cells. We believe that the damaged mitochondria may be a significant reason why kidneys from such donors have poor outcomes. To rescue these organs I am investigating whether activating the cells own defence mechanisms to hypoxia can protect against mitochondrial injury in the brain dead donor.

I am also part of a team investigating whether we can rescue organs such as the kidney and liver once they are removed from the donor. These organs are typically placed on ice for transport and storage until they are implanted into the transplant recipient. We are investigating whether restoring a blood supply to the organ by connecting them to a machine which pumps blood through the organ at normal body temperature will protect it during transport and storage.

If we don't address the organ shortage today this will have an even greater impact in years to come.

We are also looking to establish whether we can develop a 'molecular profile' of organs for transplant to assess how damaged the organs are, and whether we can predict the outcomes of the transplant based on this. This will involve establishing what happens to cellular markers such as proteins, nutrients and waste products. We are aiming to develop a type of 'barcode' using these markers, which will in the future help us decide whether an organ should be transplanted or not.

My research focusses on major challenges in organ donation and transplantation. If we don't address the organ shortage today this will have an even greater impact in years to come. By developing these new insights, my research aims to increase the number of suitable organs for transplant. I believe that this research is a crucial step towards preventing deaths on the waiting list and lifting the death sentence for thousands of patients.

Simon Armitage gave his first lecture as Professor of Poetry to a packed audience at the Examination Schools yesterday evening (Tuesday 24 November).

A full audio recording of the lecture is now available.

Professor Armitage opened with an account of 'the parable of the solicitor and the poet', in which a poet pays a solicitor for legal advice. The solicitor then asked the poet to review some poetry he had written - and did not offer to pay the poet.

By Marc West

By Marc West- ‹ previous

- 137 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?