Features

In a new paper published in the journal Nature Communications, Oxford DPhil student Suzanne Ford from the Department of Zoology shows how the use of ‘good bacteria’ – or defensive microbes – could help fight diseases.

Using a microscopic worm infected both with a host-protective microbe and a harmful pathogen, the study demonstrates that the presence of a defensive microbe can force a pathogen to become less virulent.

Defensive microbes can also ‘steal’ vital proteins from pathogens to make themselves stronger, causing the pathogens to evolve to produce fewer such proteins. This, in turn, makes the defensive microbes weaker – but enough damage has already been done to the pathogen to stifle its future growth and virulence.

In a video produced by fellow Oxford DPhil student Sally Le Page for her ‘Shed Science’ YouTube series, Suzanne explains how, in the era of antibiotic resistance, alternative strategies for disease control are of the utmost importance.

Scientists have identified the neural pathway in male fruit flies that allows them to perform their complex mating ritual, paving the way for deeper studies into sexual behaviour and how it can be modified by social experience.

A gene known as doublesex is responsible for the differences in anatomy and behaviour of males and females in many animal species. The male doublesex gene is active in around 650 neurons - specialised cells that transmit nerve impulses - with specific groups of cells controlling distinct steps in the courtship ritual. However, it was not known how these different steps are coordinated to ensure successful mating.

“Male fruit flies court females with a series of ‘hard-wired’ or genetically programmed behaviours, and failure during any part of the process may prevent reproduction,” says senior author and Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Stephen Goodwin, from the Centre for Neural Circuits & Behaviour at the University of Oxford.

In their study, Goodwin and his team identified a circuit of doublesex-expressing neurons in males that controls the act of sex itself. Located in the fruit fly’s equivalent of the spinal cord, this circuit is made up of three key types of neurons: motor neurons, inhibitory interneurons, and mechanosensory neurons.

Hania Pavlou, lead author of the study and MRC Career Development Postdoctoral Fellow in Computational Genomics, added: “We found the exact motor neurons that control the male penis and enable sex to take place, in addition to a second group of inhibitory neurons that oppose the motor neurons and are involved in the uncoupling following sex.

“Using sophisticated genetics, we are able to perturb the activity of these neurons and stop males from mating. We also show that the mechanosensory neurons on the genitals feedback and potentially coordinate the activity of the other neurons to generate the correct balance of excitation and inhibition that is needed for copulation.”

The results suggest the doublesex gene configures a circuit specific to males, which allows them to successfully execute the correct action sequence for both the initiation and termination of sex.

The findings also indicate that the mechanics of copulation are separate from those of reproduction.

It has previously been shown that sperm transfer in fruit flies is controlled by a group of neurons that supply the reproductive glands with nerves and promote ejaculation. The new study reveals that the circuit controlling the act of sex is distinct from that involved in sperm transfer, although it may still help to modulate it. This suggests a mechanism for separating the pleasant sensation of sex from reproductive function.

Identifying the neural circuits that drive behaviours in fruit flies can provide scientists with an insight into the universal principles of how a nervous system can coordinate complex motor behaviours, such as walking, flying and sex.

The full study, which was funded by the Wellcome Trust, can be read in eLife Sciences.

After a dramatic result in last week's US election, Dr Tom Packer of the Rothermere American Institute looks back at what the result means, and what we should look out for in the next few months:

A sensational election night capped a sensational election. As the dust settles, what are some of the key points to be borne in mind?

Firstly and perhaps above all else: this is an election that speaks to the power of opposition to high levels of immigration and related concerns of culture, race and nationality. Remember Donald Trump had a host of liabilities in both the primary and general election — not least the fact that consistently more voters disapproved of Trump and thought he was not qualified to be President.

One issue he monopolised in both the primary and the general election, however, was immigration and related considerations. He was the first presidential nominee since before World War II to run on a platform of restricting legal immigration. And he outperformed among voters who were concerned with these themes, along with related considerations such as fears of terrorism and opposition to free trade.

In the primary, voters concerned about immigration and related cultural concerns were the core of his support; in Florida, for example, voters who cared about immigration outscored others by 38 points. In the general election he outperformed among white voters with no college degree; it was a huge turnout among white voters with no college degree that won him the presidency and it was in the rural and working-class areas of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania that he secured his victory.

And his victory underscores another broad pattern that extends beyond American politics. When combined with the polls for other electoral decisions such as Brexit, it strongly suggests that polling tends to underrate the power of positions that are nationalist, culturally conservative or which favour immigration restrictions. It’s not simply the case that polling suggests the public is more socially conservative than its elites, but also that polls underrate that difference.

Secondly, it’s time to dismiss the idea that the Republican party is in a state of collapse. This is a narrative that has been remarkably resistant to evidence. The GOP now dominates every level of elected government in the US: not just the presidency, but Congress, state governors and state legislatures to an extent unseen since the 1920s.

The only level of US government where Democrats tie or dominate is its least democratic branch — the federal courts. And that is unlikely to stick for long. Nor can one make this a simple Trump effect — the GOP did better in 2014 and Senate candidates this election cycle seem to have run ahead of Trump as much as behind. The strong vote by practising Christians for the GOP this election speaks to the electoral advantage the GOP has gained by Democrats’ embrace of a strongly liberal ‘moral’ (but secular) agenda.

This does not mean the GOP is invincible. Mr Trump is at minimum a highly unorthodox figure in whom a party should be wary of placing their future. But at this moment if there is a majority party in America it is the Republican party — for the first time since the 1930s. It is the Democrats who’ve been in denial.

Thirdly, the infrastructure of campaigns and party establishment should be regarded much more sceptically. There was a huge emphasis by commentator and political operatives on how much better organised the Clinton campaign was than Trump’s, which was possibly the least well-organised and run of any major party candidate for decades.

Trump got less formal campaign support at both elite and popular level than any Republican major party nominee since at least 1964: neither of the living Republican presidents voted for him or supported him, while the Clinton campaign mobilised everyone from President Obama to previously non-political celebrities like LeBron James to thousands of volunteer advance organisers across the country. The fact Trump won doesn’t mean it didn’t matter — he might have won by much more otherwise. But it does suggest its impact is limited.

Finally, the massive shock to world politics has opportunities for the UK as well as disadvantages. One factor that has been neglected is the impact on the UK’s Brexit negotiations. Mr Trump has talked up the positive side of Brexit, effectively endorsed it and talked about a potential ‘great deal’ between Britain and the US. His closest ally in UK politics is Nigel Farage.

This suggests that as the UK leaves the EU he could potentially be helpful. The possibility he will be less ready to underwrite Europe’s defence also makes those European countries with a powerful military much more important — a category that very much includes the UK.

Mr Trump has revolutionised US politics it remains to be seen what will follow next.

More Oxford academics gave their take on the election here.

2016 marks the 75th anniversary of the first human trials of penicillin. As news stories announcing antibiotic apocalypses and new superbugs grow, Back from the Dead, a new special exhibition at the Museum of the History of Science at Oxford University, charts the miraculous and precarious history of penicillin from the trials in the 1940s to the present day.

Back from the Dead will explore current responses to the challenge of antibiotic resistance. This includes a collaboration with the multi-disciplinary team of the Oxford Martin School Programme on Collective Responsibility for Infectious Disease where visitors will have an opportunity to contribute to current research on antibiotics through interactive questionnaires.

The Museum’s Director Dr Silke Ackermann says: 'Back from the Dead brings together past science with contemporary medical challenges in a novel way, revealing an extraordinary Oxford story and the human face of research in dramatic times.'

The global scale of penicillin’s success in the 20th century, and the worldwide challenges that face antibiotics now, contrast with the small-scale work which led to its development. While Fleming is the name now most associated with the ‘wonder drug’, he was never able to stabilise and test his tantalising discovery.

In addition to its contemporary dimension, Back from the Dead also showcases the Oxford researchers responsible for penicillin’s transformation from promise to success. An international team led by Professor Howard Florey and based at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford isolated the antibiotic and conducted the first clinical trials.

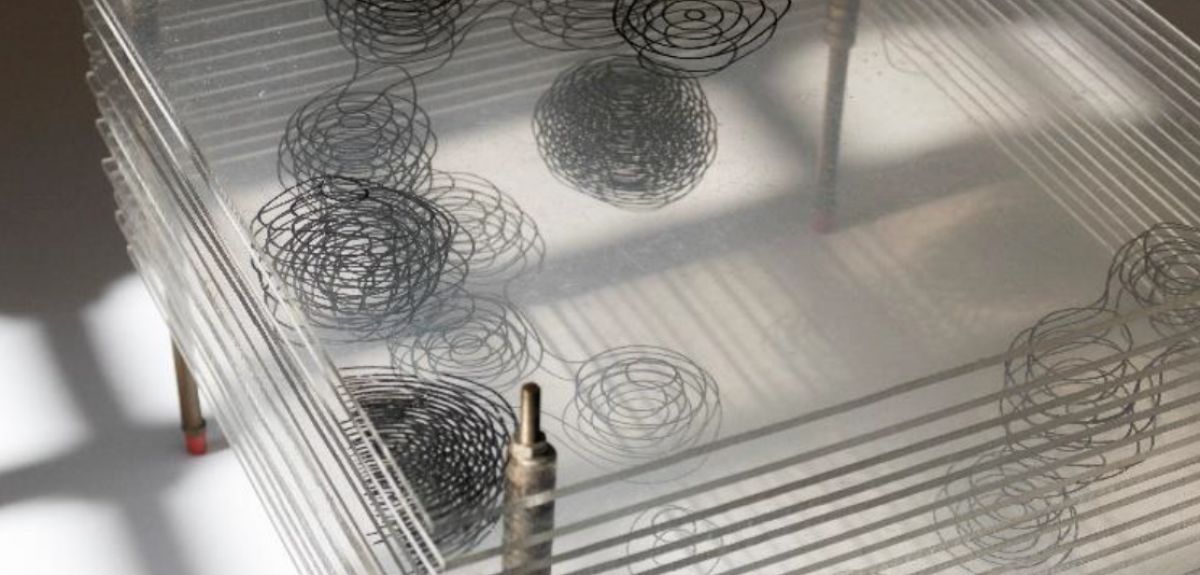

Back from the Dead draws on the Museum’s own collections to highlight the hand-to-mouth character of research in the early days of World War II. Bed pans, biscuit tins, and cans of sheep dip were all initially used as convenient vessels in which to culture the penicillium mould. In a world of make-do-and-mend, the insights of Ernest Chain, a Jewish German refugee biochemist, were balanced by the ingenuity of Norman Heatley, who conceived the temperamental apparatus by which penicillin was purified.

Crucial work to determine the structure of penicillin was also carried out in Oxford, by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin and a small team of x-ray crystallographers in the 1940s. Still the only British woman to receive a Nobel Prize for science, Hodgkin’s work is revealed in the exhibition both by the painstaking labour of molecular model-making and the vivid insights of her personal correspondence.

Sponsored by the EPA Cephalosporin Fund, the Back from the Dead exhibition will be combined with an exciting programme of public events, education work and digital resources. This generous support has also allowed for the conservation of apparatus and archives in the Museum’s collections and will permit a subsequent permanent redisplay of this important material.

The exhibition will run until 21 May 2017.

When a drop of liquid hits a surface at a sufficiently high speed, it splashes – that much isn't in doubt. But sometimes splashing isn't helpful. Researchers are working on methods of 'splash avoidance' that could prevent splashback of harmful or unhygienic fluids in a range of settings, from hospitals to kitchens – and perhaps even urinals.

In a new paper led by scientists at the University of Oxford and published in the journal Physical Review Letters, researchers show that coating a surface in a thin layer of a soft material like a gel or rubber could provide a simple solution to this problem.

Lead researcher Professor Alfonso Castrejón-Pita, Royal Society University Research Fellow in Oxford's Department of Engineering Science, said: 'We realised that no one had actually studied systematically what happens when droplets hit soft substrates. In our study, we dropped ethanol droplets on to soft materials made of silicone – the material often used in bathroom sealants. Silicone is very useful, as it can be made to have different levels of stiffness, ranging from a material comparable to jelly to something with a consistency more like that of a pencil rubber.

'We filmed the impacts with a high-speed camera at speeds of up to 100,000 frames per second – around 4,000 times faster than a typical mobile phone – and then studied the splashing dynamics. Combining these experiments with some theoretical modelling and detailed computer simulations, we found that tiny deformations of the substrate occur within the first 30 microseconds after impact, which, surprisingly, can be just enough to completely suppress splashing.

'What is most surprising is that you need about 70% more energy to get a drop to splash off these soft materials when compared with hard materials. If you think of a drop falling from a certain height, we need double the height to make it splash in the softest surfaces.'

There has been little work carried out into splash avoidance. It has been demonstrated that droplets in a vacuum don't splash, and droplets hitting a thin, elastic membrane are much less likely to splash. Moving the substrate at high speeds may suppress splash on one side of the drop but enhance splash on the other side. No one as yet has looked at how simple coatings could provide all-round splash protection.

Professor Castréjon-Pita said: 'We believe soft surfaces with the correct stiffness could be used in a number of situations in which "dangerous" or "nasty" fluids are used. It's surprisingly easy to for droplets to turn into aerosols or sprays when they splash: a drop of a typical solvent such as ethanol or methanol will splash if dropped from a height of around 20cm and will generate droplets of that material that can be carried away by air. So if you're working with dangerous chemicals or biomaterials, it would be helpful to know that you won't be generating sprays or aerosols if some drops fall, exposing you to diseases or harmful materials. This is also the case with the use of instrument trays during surgery – this technique could prevent the splashing of bodily fluids.

'As for hygiene, the transmission of campylobacter or other food poisoning agents in a typical kitchen is one example. In the UK, there is a big campaign to stop people from washing raw chicken before cooking because of splashing. A surface capable of stopping accidentally spilled drops of raw chicken fluids may be useful. And the development of a splash-free urinal would also be welcome!'

Professor Castréjon-Pita added: 'There's certainly more work to be done in this area. The softer you make a material, the stickier and weaker it often becomes – two things which aren't ideal for making useful, long-term coatings. The main challenge of this work is how to overcome that. Luckily, recent work has started to develop new materials that can be soft, strong and non-sticky – like tough hydrogels – so there are certainly a lot of approaches to be explored.'

- ‹ previous

- 112 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators