Features

As part of our Women in Science series, ScienceBlog meets Professor Tamsin Mather, a volcanologist in the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford University. She discusses her professional journey to date, including recent work with the education initiative Votes for Schools, and why science is the best game around.

What is a typical day in the life of a volcanologist like?

Volcanology is incredibly varied, so there is no typical day. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

What has your professional highlight been to date?

There have been lots, but one of the most exciting was finding fixed nitrogen in volcanic plumes in Nicaragua.

All living things need nitrogen to survive. Although Earth’s atmosphere is mainly made up of nitrogen, its atoms are very tightly bonded into molecules, so we can’t use it. To do so, you need something to trigger their separation. For example, when lightning strikes, the heat prompts atmospheric nitrogen to react with oxygen, forming nitrogen oxides or “fixed nitrogen”. We discovered that above lava lakes, volcanic heat can have the same effect.

Volcanology is incredibly varied. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

Why was the discovery so interesting?

The research shows how volcanoes have played a role in the evolution of the planet and the emergence and development of life.

But that particular trip looms large in my memory because we were robbed while getting the data. I remember it vividly, we had waited all day at the crater edge for the plume to settle, but the sun set before we had a chance to take our measurements. We went back to the national park early the next day, before the security guards arrived, and got robbed at gun point. In retrospect we should have known better, but excitement got the better of us. A terrifying experience but thankfully no one got hurt. We didn’t even get great data that day in the end.

How did you come to specialise in volcanology?

By mistake. When applying for my PhD I put ocean chemistry as my first choice, but I was stumped for my second choice, so browsed the list of topics and the atmospheric chemistry of volcanic plumes stood out to me. I got more and more excited as I read about it, and ended up switching it from my second to first choice. I haven’t looked back.

Do you think being a woman in science holds any particular challenges?

The statistics bear it out - we are still in the minority. There are lots more women in more junior levels now and that will filter through eventually. I definitely would have appreciated more visible female scientist role models when I was younger, but I think the perception of science as a male pursuit is eroding.

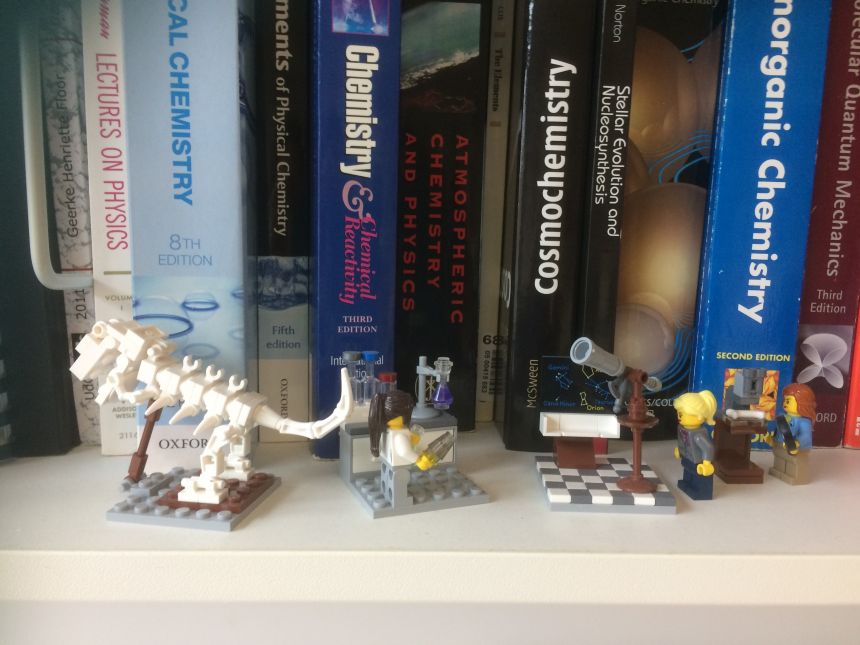

For instance, I used to love Space LEGO, but there wasn’t much diversity in the astronaut characters that came with the kits then. Now, my primary school age daughter loves it too, and the kits are much more diverse. I even have the all-female Research Institute kit in my office. The landscape has changed a lot in the last 20 years, but there is still more to be done.

There isn’t just one solution. Whether in relation to gender or ethnic diversity in science, it is a multi-component problem. If someone is the only woman or ethnic minority in their group, they may feel there is no future role for them. There are so many influencing factors in this situation and they are not all easily articulated or solved.

Science is the best game around. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

What do you think can be done to encourage more diversity in science?

One of the key challenges for women in academia is the transition from PhD student, to post doc level and on to permanent faculty member. Often at that stage scientists have to relocate frequently. Some of my female contemporaries found this difficult and wanted more stability. Maybe they wanted to be close to a partner, or were thinking about having children. That is not an easy problem to solve and it can be difficult for men too.

There are things that can be done to make this journey easier. Programmes that provide flexible working patterns for outstanding scientists, like the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship scheme, work well, for instance.

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin Mather

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin MatherWhat are you working on at the moment?

We are studying the volcanoes of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia. Little is known about the history of these volcanoes and how often they erupt. But by measuring the layers of ash that have deposited around them, we can learn more about past and present volcanic activity. It’s possible these volcanoes could be used as energy sources in the future and we are investigating their potential for geothermal development.

How did you get started in science?

I always found it fun and really wanted to be an astronaut, but when I was seven I had an ear operation which killed that dream.

How did you come to be involved in Votes for Schools, the education initiative supporting children to have informed opinions?

It’s a great way to get young people thinking critically about the difference between opinions and facts. We have to empower young people and make sure they realise why having a voice matters. It is important to have an informed opinion, no matter your age. I was asked to join the Votes for Schools team, visiting Packmoor Ormiston Academy to talk about being a female scientist and to launch the primary school version of the scheme.

How did the children respond to your question, ‘Do we need more female scientists and engineers?’

The majority (61%) felt that there were not enough female scientists. The statistics of under-representation, arguments about diverse teams performing better, and the importance of engaging the whole of society in science were key here. Those that responded no, felt women have the right to choose what they want to be, a scientist or otherwise. Cultural background came into play as well, with some saying that women should stay at home.

What were your main takeaways from working with the initiative?

Questions like ‘do you ever work on metamorphic as well as igneous rock?’ really surprised me, and the enthusiasm of staff and children alike was fantastic. They really understood the issues and were not afraid to express their opinions. Technology is so central to our lives now, compared to when I was at school. Smart phones and computer games have become key to how we socialise and have fun. Science and technology are certainly not just for geeks anymore!

What advice would you give to someone considering a career in STEM?

Do it! It’s the best game around. There are so many doors that a career in STEM opens for you. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new computer games or apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

Dr Matthew S. Erie, who is Associate Professor of Modern Chinese Studies at the Oriental Institute, has been named a Public Intellectual Fellow by the National Committee on US-China Relations (NCUSCR).

The Public Intellectuals Program (PIP) was launched in 2005 to nurture the next generation of China specialists who have the ability to play significant roles as public intellectuals.

PIP Fellows gain access to senior policymakers and experts in both the United States and China, and to the emerging business and nonprofit sectors in China, as well as the media.

Dr Erie says: ‘I’m honoured to be named a PIP Fellow by the NCUSCR. As a PIP Fellow, I am fortunate to engage in a number of workshops in the U.S. and in China to create synergies between the academy and policy circles in the U.S. and China.

'There is a lot of work to do to increase education on and general awareness of Islam and China. The NCUSCR, and PIP in particular, provides a platform for scholars to hone their message to reach wider publics.

'One of the key priorities to me is to close the gap between those who either promote or fall prey to anti-Muslim or anti-Chinese sentiment, on the one hand, and those who work in the academy, on the other hand.'

Being named a PIP Fellow helps China scholars to broaden their knowledge about China's politics, economics, and society, and encourages them to use this to inform policy and public opinion.

Last year, Dr Erie published ‘China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law’, which looks at how shari'a (Islamic law and ethics) is implemented among the Hui, who are one of 10 officially recognised ethnic groups in China. Being a PIP Fellow could help him to get his research across to broader audiences in China and the US.

'Islamophobia, in particular, has emerged as one of the defining social pathologies of the twenty-first century,' he says. 'We can see its impacts from Brexit to Trump’s America to the ascendance of nationalist political parties in Western Europe. Islamophobia is not just a “Western” phenomenon but over the past year or so has intensified in places like China.

'One common misperception fuelling Islamophobia is that shari’a (a term heavily debated by Muslims but which generally means “Islamic law and ethics”) is somehow creeping into state law. In my book, I argue that Chinese Muslims (Hui) practice a form of shari’a with soft edges, and that the very informality of shari’a in China allows for both Hui and state actors to make arguments based on shari’a for their notion of the “good”.

'In other words, Hui do not impose shari’a over non-Muslims, but rather, Hui and the state alike make use of the authorities, texts, and symbols of shari’a as material to fashion their ideas of society. While such constructions create conflicts, the book illustrates that shari’a can also provide a “middle ground” between Muslims and non-Muslims.

'By focusing on the case of China, a country that is commonly perceived as either “authoritarian” or “lawless,” I hope to demonstrate the adaptability of shari’a. While it can create conflicts with state law, it can also facilitate economic development, contacts with other developing states, and ethical action."

Dr Erie explained his research in more detail in an interview with the New York Times last year.

More information about the programme can be found here.

Mrs Mica Ertegun has been made an honorary Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE), an award conferred by HM The Queen for her services to philanthropy, education, and British-American cultural relations.

The award recognises Mrs Ertegun’s support for humanities postgraduate education in the UK and in particular her establishment of the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities - open to students worldwide - at Oxford University in 2012.

Mrs Ertegun has endowed the university with substantial funding for post-graduate research in the humanities, under the Ertegun Programme, which will include the endowment of graduate scholarships in perpetuity. This is the single largest philanthropic gift for the humanities at the University of Oxford.

Since 2012, Mrs Ertegun’s gift of £26 million has enabled 45 leading humanities scholars from 16 countries around the world to study and research at Oxford University. Among those Ertegun Scholars who graduated in 2015, 80% received distinctions. Ertegun Scholars’ research areas have included literature, history, music, archaeology, art history, ancient history, Asian studies, Middle Eastern studies, and medieval and modern languages.

Born in Romania, Mrs Ertegun is a citizen of the USA, and received her CBE in a special ceremony in New York. Antonia Romeo, British Consul General New York and Director-General Economic and Commercial Affairs USA, said, “The awarding of Mica Ertegun’s CBE recognizes her exceptional transatlantic philanthropic activities, and her major contributions to British-American cultural relations. These charitable efforts and initiatives, especially via the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities at Oxford University, are key to the growth of generations of future global academic leaders.”

Established in 2012, the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities at Oxford University provides recurrent annual funding for a population of 15 – 30 graduate students, known as Ertegun Scholars. In addition, Mrs Ertegun has overseen the conversion of an Oxford University building into an academic base for the students, Ertegun House, and established an annual lecture programme.

More information on this story can be found here.

More information about the Ertegun Scholarships and life at Ertegun House can be found here.

Although women in science continue to be underrepresented at the highest level, things are slowly changing. In a complex but changing culture, many have built highly successful, rewarding careers, carving out a niche for themselves as a role model to budding scientists, regardless of gender.

In honour of the forthcoming International Women’s Day (March 8th 2017), over the next few weeks, ScienceBlog will be turning the spotlight on some of the diverse and accomplished women of Oxford. Women who, in influencing and changing the world around them with their work, are inspiring a new generation of young people to follow in their footsteps.

Bushra AlAhmadi is a DPhil student in the Department of Computer Science, specialising in cyber security. In 2016 she was awarded the prestigious Google Anita Borg scholarship for women in technology and co-founded the community outreach initiative, InspireHer. The initiative aims to build on young girls’ interest in computer science, by engaging both parent and child with a fun and interactive coding workshop.

How did you come to choose computer science as your field of expertise?

I had a head full of ideas and naturally really enjoyed computer programming; building something from scratch and teaching it to do things. Being able to make something do what you want is both useful and powerful – and that is all coding is. People are just starting to realise that as a skill, it can be useful in lots of areas - not only science areas like engineering, robotics, website development and computing, but also business, law and even retail. It has allowed me to work in multiple fields: programming, security, network security and now cyber security. The freedom of variety to do what you want is really appealing.

What are you currently working on?

My research involves designing malware detection systems, specifically in Software Defined Networks (SDN). Day to day, it involves a lot of coding and testing, trying to find ways to detect and prevent malware. At the moment I am working with external security operation centres' (SOCs) and analysts to understand how they detect malicious activities on the network.

What do you find most challenging about being a woman in science?

As a Saudi Arabian, who completed her master’s degree in California and now lives here in Oxford, I think being a woman in science depends on where you are. Saudi Arabia is actually the place where I feel least aware that I am a 'woman in science'. My university, King Saud University, is divided into single sex campuses, and we actually have an equal number of female and male students studying computer science, if not more. There are around 1,000 female computing undergraduates as well as Master's and PhD students, so we don’t see ourselves as female scientists, just scientists. But, both in the USA and UK, I was always aware of being a minority in my field. Often you are the only woman in your study group.

We need more women and ethnic minorities working in tech, so don’t be afraid to apply just because you are different. In my case it has only been an asset.

In the early stages of my pregnancy, I didn’t want people to think I was less capable of doing my work, so didn’t tell anyone at first and became quite isolated and homesick. But, when I did tell my tutors, the support I got from the university was great, and made me wish I had done so sooner. Everyone from my supervisors to the administrators, went out of their way to make me feel comfortable. Female professors are still a minority at Oxford, but they openly talk about their experiences as women. It’s so important to have relatable role models who talk about motherhood, rather than hiding it away like it is wrong, or that in doing so they are making excuses.

When I attended my first seminar after having my son, I was really nervous. My professor pulled me aside and said: 'if you need to bring your child to a lecture or a meeting, just do it – I have.' It instantly put me at ease and made me realise, it didn’t matter. She was a mum too, like lots of other female scientists. They do not let it hold them back, so I never have either. As a woman and an international student, you feel very welcome and safe here. With everything happening in the world at the moment, I feel very lucky to be here.

What accomplishments are you most proud of to date?

Winning a place on the Google Women Techmakers Scholars Programme, which was formerly known as the Anita Borg Memorial Scholarship Programme (offering financial support to people studying computer science at under graduate or graduate level) was a great honour. On a personal level, doing a PhD while pregnant and having my son in my first year of study is something I am very proud of.

What led you to set up InspireHer?

Female professors are still a minority at Oxford, but they openly talk about their experiences as women. It’s so important to have relatable role models who talk about motherhood, rather than hiding it away like it is wrong, or that in doing so they are making excuse.

As part of my scholarship we were asked to come up with outreach ideas and as a mum, I wanted to engage parents as well, so that they can support and encourage their child’s interest in computer science.

InspireHer is a programme for young girls, who with their parents can become inspired through coding. Through the programme, I often meet parents who think that exposure to technology is bad for their child's development. There are lots of computer and smart tech games that can help children with their maths and science skills development.

Programmes like SCRATCH encourage children to create their own stories, animations and videos.

What can be done to encourage more young girls to choose a career in STEM?

Research suggests that if we want to see more women working in the STEM sciences, we have to engage them at an early age. Having a parent to help and guide them helps feed a child’s interest and boost their confidence. If parents do not understand or value computer science, then their children are not likely to either.

Strong, encouraging role models are really important, especially for younger children (under five) who would not know where to look for coding activities on their own. I am very proud to be a woman in science. There are some great female computer scientists, but to stay that way, we need a new generation to follow suit and a generation after that and after that. Workshops like InspireHer allow young girls to build on their interest in computing, practice activities and then decide for themselves if it is the right career for them.

How can schools better support children interested in science?

Some of the girls attending InspireHer events say they love science, but find school boring. Coding is an interactive and fun way to learn as it is multi-disciplinary and a good skill to develop, whatever field you decide to go into. Teachers could use the robotic ball exercise to make maths and science lessons more hands on. We use it a lot at InspireHer events and the children respond well to it. They learn to code and control the ball, coordinating its movements by using drag, drop and pause options. The game encourages the same step by step approach and problem-solving skills as playing with LEGO or building blocks.

What are your goals for the future?

I am participating in the first Saudi Arabian Cyber Security Contest, which in light of the recent cyber-attacks on Saudi Arabia, is a big deal in my country. Twenty finalists were chosen out of 500 entrants.

When I complete my scholarship in 2018, I will return to Saudi Arabia and teach coding to undergraduates. I am also preparing to launch my own cyber security consultancy business, which I hope will support government and private organisations to develop and build their cyber security capabilities.

What advice would you give to anyone considering a career in computer science?

Believe in yourself and you can make a great impact in any field, especially tech and computing. Don’t be afraid to take the lead, firsts only happen because someone makes them happen. When I started at King Saud University, the only student society was for male law students, (there was nothing for women). I started the first IT Society for Women, organising coding workshops and tech talks. I’ve also been involved with Oxford Women in Computer Science since I arrived at the University in 2014, and was President of the group from 2015 - 2016. We organised the second Oxbridge women in computer science conference, bringing together female researchers from Oxford and Cambridge. Of all the sciences, computing really benefits from and needs diversity. We need more women and ethnic minorities working in tech, so don’t be afraid to apply just because you are different. In my case it has only been an asset.

The doctor who created Frankenstein’s monster has been played on stage by a woman, for what is believed to be the first time.

A new play at the Northern Stage in Newcastle, features one Dr Victoria Frankenstein as the lead role in Selma Dimitrijevic's adaptation of Mary Shelley's iconic novel.

It's a fascinating idea, according to two of Oxford University’s experts on Mary Shelley.

‘The original novel is about a perverse, lone, male scientific kind of creativity, embodied in the character of Victor Frankenstein,’ says Professor Karen O’Brien, an expert in eighteenth-century literature and Head of Oxford’s Humanities Division.

‘Victor's creativity cuts him off from the normal, domestic world of women and female fertility. He gives life to the monster, not coincidentally, shortly after the death of his own mother.

‘So a female Frankenstein is a fascinating idea. How might the female fertility and genius be linked? In the novel, the Creature, or Monster, actually resembles the female heroines in Mary Shelley's mother's novels - isolated, sensitive, forever excluded from mainstream society by their inability to find happiness on the unequal terms offered by men.

A female Frankenstein is a fascinating idea

Professor Karen O'Brien

‘This adaptation transfers that outsider role to the scientist character. So how are we to interpret the Creature?’

Fiona Stafford, Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University, was interviewed about the casting on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

She says: ‘Mary Shelley would have been aware growing up in an unusual, avant garde household that, although she was a very intelligent woman, there was no opportunity for her to train as a doctor or to go to university.

‘In many ways you can read Frankenstein as a critique of male obsessive pursuit and of not thinking through the consequences of his actions, so it is interesting to see how that translates into Victoria Frankenstein.’

‘You can read the book in many different ways and I think that is part of the secret of its enduring success, it is extraordinary that a novel that was published in a fairly modest form in 1818 should still have this afterlife.

'In a way that is something that Mary Shelley’s myth is visiting, the idea that you can create something and then you don’t actually have control of it, it has a life of its own.

‘In some ways you can see a parallel between Mary Shelley the novelist and Frankenstein. Although we tend to think of him as a scientist, she too is bringing together something and bringing it to life, and then it has taken on a life of its own to the extent that the Creature is often thought of as Frankenstein.’

Professor Stafford's interview can be heard here.

Professor O'Brien will also be interviewed by BBC World Service's The Forum on Saturday 18 February. The recording will be found here.

- ‹ previous

- 103 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?