Features

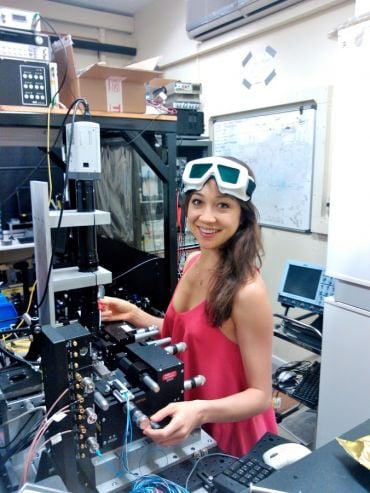

Merritt Moore has achieved what some would call ‘the impossible’: a career as a professional ballet dancer and as an academic quantum physicist. Having quite literally danced her PhD, she is just months’ away from completing her degree in quantum and laser physics. Immediately after graduation she will fly to China to perform at the Beijing National Theatre. Having danced since childhood, she sees great crossover between dance and quantum physics. Earlier this year she combined her passions, collaborating on a meditative science-influenced virtual reality experience called Zero Point Virtual Reality, which is currently running at the Barbican Theatre.

Scienceblog met with Merritt to learn more about fusing her talents and achieving success on her terms.

How did Zero Point Virtual Reality come about?

I have danced In a few of [choreographer] Darren Johnston’s productions, including his original Zero Point live performance in 2013. He takes a spiritual approach to his craft, and would often talk about ‘zero-point’ as a state of calm and zen. I introduced him to the concept of zero point energy as a physics phenomenon. A concept that means that there is always energy, even in empty vacuum, where one imagines no energy could exist. When the Barbican invited Darren to bring back his live production Zero Point, it was a natural progression to continue investigating the notion of ‘zero-point’, but this time using technology and dance. This led us to the virtual reality extension of the show.

We put our ideas together and collaborated with the Games and Visual Effects Lab at the University of Hertfordshire, and now we have a meditation experience running in 360° virtual reality (VR), at the Barbican. The end result is sublime and unique, and I hope people like it.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.In what way did you draw on your physics background for the production?

It is an interactive, sensory experience, people walk from scene to scene, taking in the themes. There are quite a few quantum physics-based elements included. For example, in quantum mechanics the systems are constantly evolving, but the minute you try to measure or interfere with them, they stop. We’ve incorporated this by having a moving rock that only moves when you are not looking at it. The approach is very subtle, and a non-scientist probably wouldn’t spot the connection, but it is there. Hopefully it will trigger people to think in a different way.

I’ve always felt that physics and dance have a lot in common. I have a confession that I sometimes read more physics papers when I am preparing for dance meetings than I do for my own research. It inspires me and makes me think about a process, and how I would explain it to someone without all the lingo and technical terminology that we scientists are so used to. Sometimes we ourselves get so lost in jargon, that we forget what things mean, so how can we expect anyone else to understand? The dance community are not scientists, so they ask a lot of ‘why’ questions, which can really throw you. In science, people rarely ask why? They work from facts, so it just is the way it is. It challenges you to think differently and try harder to break things down.

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

How would you like people to react to it?

The main purpose is to inspire people to view ideas from a different perspective, (literally since with VR you can be placed anywhere). I don’t want to just regurgitate facts, I want to encourage people’s curiosity.

When did you discover your passions for science and dance?

I started dancing when I was 13, which is considered middle-aged in the dance world - most people start as toddlers. Before I discovered dance I was just a girl who loved maths and solving puzzles. I didn’t talk until I was three, so I would communicate through my puzzles. Then I found dance, and was just like ‘this sits in the box of non-verbal activities, I dig this!’ And then, when I found physics, I felt the same way.

You are in your final year at Oxford, what is your thesis investigating?

I am currently working to create large entangled states of light. The more photons - particles of light, you use, the harder it becomes to maintain their quantum properties. Adding more photons makes the whole project more vulnerable to noise, which can destroy their natural state. Understanding how photons behave when you interfere with them can help scientists to explore quantum mechanics phenomena.

Image credit: Merritt Moore

Image credit: Merritt Moore

What drew you to physics?

I love the creativity. Visualising and probing problems that have never been solved before requires a lot of imagination. Often it is mind-bending, and makes no sense. Quantum mechanics is so bizarre - even though the experiment proves again and again that it works, it still makes my head spin.

How do you manage two successful careers in two different fields?

I’ve retired from dance about ten times, burnt my ballet shoes and tried to get so out of shape I would never dance again, but I always come back to it. I honestly never thought I would be a professional dancer. A dance career was a no-go in my family. But I always worked really hard, and achieved the grades I needed. So, when I got to [Harvard] university I was in a position to take a year off to dance with the Zurich Ballet Company. After that I returned for a year, and did the same again the following year, with the Boston Ballet. During the winter break at Oxford I performed with the English National Ballet, and right after leaving here, I will be in Beijing and then on to Edinburgh and Cuba.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a struggle. I’ve worked a lot. Yes, there have been times that I have felt overwhelmed - when I have been in the lab for over 20 hours a day, sometimes literally sleeping there. But it has always been fun. I’ve realised doing both actually helps me to relax. It’s exercising a different part of the brain and the body and I need it.

What is your ultimate goal?

I haven’t figured out what my title will be yet, but I want to shatter all the stereotypes. The dream is to continue combining physics and dance. I want to dance for the next 10 years, become a principal dancer with a company, and still publish physics papers. I was inspired by the film Interstellar, which, for authenticity, channelled real science into its stunning visuals. Physicists shared insights on black holes and worm holes, and they were converted into special effects for the movie. If I’m able to do something like that, then life is complete.

Quantum physics is one of the more polarising sciences, why do you think that is?

Honestly I think physics in general is really under-sold at school. Classes tend to run the same way, with the standard set of problems that have been done so many times that they are probably online. It’s hard to inspire someone when they know that they can google and memorise the facts. That’s not learning. Technology has evolved so far that most of the information is already there. The asset that we bring to the table, as human beings, is creativity.

I think the way science is taught in schools is very isolating, and self-selecting. There is a misconception that science is technical and geeky, but it is collaborative, imaginative and so much fun.

Do you think that there are any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally have never thought that there is anything that a man can do that a woman can’t. So I had always made a point of avoiding the “women in science” physics societies. I felt that by going, I was making a statement that I saw a difference. But, last year I went to my first meeting and it was amazing, and I thought ‘why didn’t I come sooner?’ I really valued the female camaraderie, and hearing people’s shared experiences. It made me realise that there are serious issues. The ratio of women to men in physics has barely budged in 40 years. You hear a lot of talk about change, but the numbers tell a different story.

Little things make a huge difference, particularly to young girls, and I had no idea. I was having lunch at a young STEM event, for girls aged 11-13. One girl causally looked up at a line-up of the old portraits and said ‘oh there’s a woman - I guess she’s the wife or something’, and the girl next to her said ‘Probably not important.’ My heart sank. I had heard of the Oxford Diversifying Portraiture initiative but never thought anything of it. I would shrug my shoulders and think ‘oh well, it’s history’. But listening to the girls’ highlighted how much, if we really care about getting more girls in science, every little change matters.

Zero Point Virtual Reality is running at the Barbican Theatre until 28 May

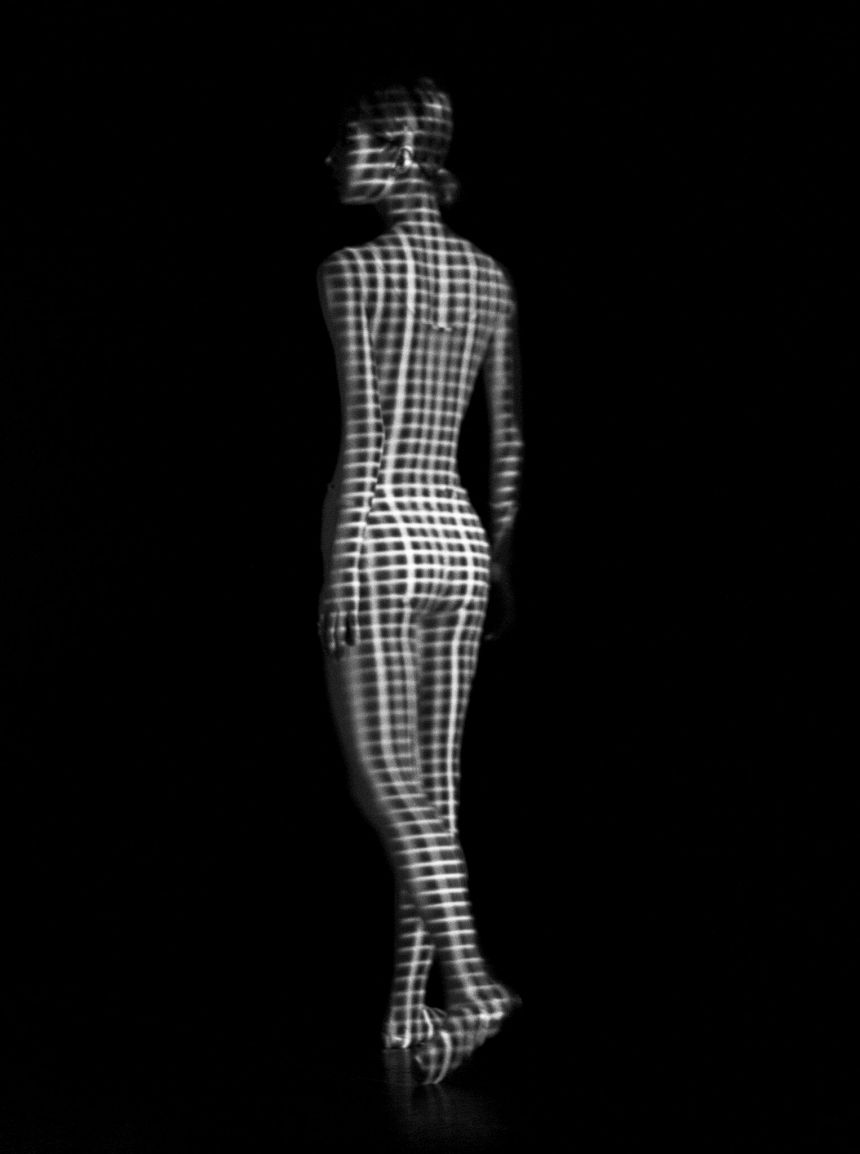

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

In today’s political climate, science’s value to society is under threat and consistently questioned.

Yet in our everyday lives we reap the rewards of research without even realising it. Take chemistry, for instance. From the flavourings in the food we eat, to the fragrances we wear and the life-saving pharmaceutical drugs that we rely on, the field has a phenomenal impact on the world at large. But this impact often comes with a financial and environmental price attached.

A new Oxford Sparks animation, developed in collaboration with Dr Holly Reeve of Oxford University’s Department of Inorganic Chemistry, breaks down how scientists are working to make the chemicals they produce both cleaner and greener, by highlighting the value of applied science in a real world context. Dr Reeve is co-investigator and manager of HydRegen, an innovative, early-stage, yet already award-winning technology. The product’s name is a play on how it recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Learn more about HydRegen here:

Dr Reeve talks to scienceblog about her role in taking one of the university’s most exciting innovations to market and why academics need to get real about science.

Where did the idea for HydRegen come from?

It was the brainchild of my Professor Kylie Vincent’s and our collaborators Oliver Lenz and Lars Lauterbach’s at the Technical University in Berlin. At the start of my undergraduate Masters project, Kylie challenged me to achieve hydrogen driven co-factor recycling by adding two particular enzymes to a carbon particle, the end result hopefully being a method for cleaner, safer chemical products. We had no idea if it would work, but she is a great mentor, and I believed in her vision. After trying every day for six months, we finally cracked it.

The market for HydRegen could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How could HydRegen be used?

HydRegen is a clean way of using enzymes to carry out very specific hydrogenation reactions that are essential steps in the production of many chemicals. The market could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How has the project evolved over the last three years?

In 2013 we entered the Royal Society Chemistry Emerging Technology Competition and won a prize package which included mentoring. This helped us to start networking and form a picture of the impact that we could have. We then met with Oxford University Innovation, and quickly began to build a picture of the project’s real world value. I then carried on the research as my DPhil project.

Oxford is such a renowned institution, so the opportunities for development are endless. It is a very entrepreneurial environment that offers great training. Supported by Jesus College and the Maths, Physics and Life Sciences (MPLS) division, I was able to take a business and innovation course which has really helped me develop the skills I need for this industry-facing project.

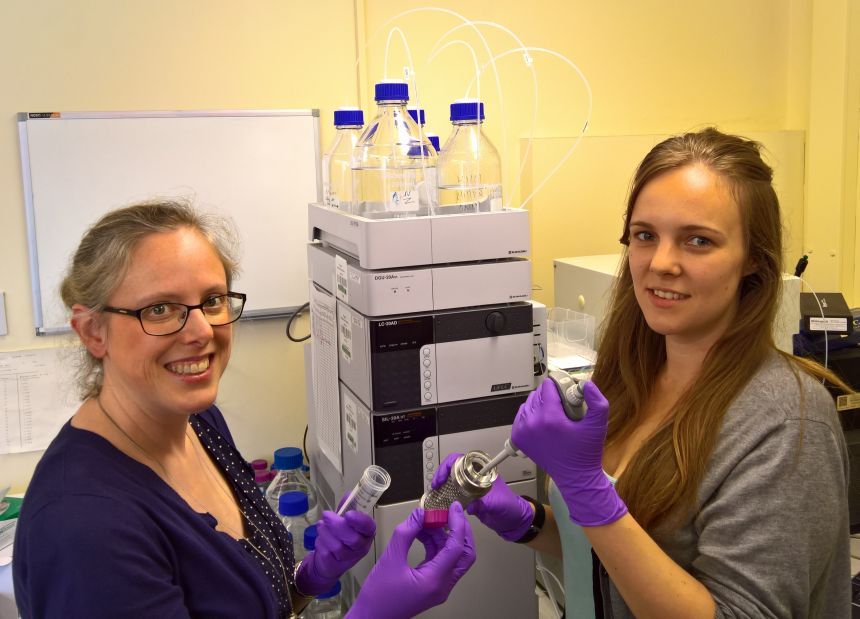

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OU

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OUA lot is often said about innovation, would you describe the University environment as particularly innovative?

I think it is a word that confuses people. To me, innovation is about having great ideas with real world applications, and then working out the best way of achieving them. Oxford is overflowing with great research, which is a pretty good start for that.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits.

The growing number of entrepreneurial opportunities mean we now have more and more commercially aware scientists, who are driven by applied science. I think the next generation of scientists are going to have even more to offer. The entrepreneurial training and funding offered make innovation even more attainable, all we need now is more incubator space.

When do you envision the product being available for commercial use?

We won Innovate UK/EPSRC/BBSRC funding in 2016, for a five year grant worth £2.9 million. The aim is to launch HydRegen as a spinout by the end of the project, within the next four years. However, we are currently mapping out some new, related ideas which could get us to market sooner.

What challenges do you anticipate along the way?

At the moment the process works nicely but on such a tiny scale that it couldn’t be implemented in industry, so the challenge is in the scale-up, For instance, trying to make the enzymes required on a larger scale and to implement them cost effectively. Basically, convincing industry that we can ‘beat’ their existing processes on cost, as well as on our ‘green’ credentials.

We often find our academic curiosity and our commercialisation time-line can be conflicting. However, our academic curiosity is what got us here, and we have already come up with some new ideas since we started this project. Overall, it’s a tricky balance between the two, but both are really important to our success.

What are you working on at the moment?

In collaboration with industry partners, we are testing the product’s industrial attainability. Our team has grown from just Kylie and myself to eight members, and each member is working on a different aspect of this scale-up. Understanding the feasibility of mass producing the enzymes and catalytic beads will help us understand how HydRegen could eventually be useful to industry. Next up though, we have some patents to file. Looking forwards, our focus will be on writing a business plan and generating investment.

What learning curves have you encountered building a start-up company?

I try to live as if HydRegen is already a spinout, and as if every decision I make could cost us money. This makes me think slightly differently (balancing the academic and commercial aims of the research) and means I try to present myself more professionally – you never know when you might meet a potential investor or partner company. I often spend the first few minutes of a meeting working out whether I need my academic or business hat on.

As scientists we get really used to interacting with people like us, but outside of the industry people communicate in different ways. A big lesson for me was going to a course in the business school which was a mixture of scientists and MBA (Master of Business Administration) students. The MBA students were more interested in the business potential of the project, rather than the scientific detail.

I learned to break the message right down, to make it quickly accessible to everyone. Even into snappy one liners that really underplay the science involved – which as an academic is quite unsettling, But at the same time necessary.

How do you think scientists could better engage with the public?

I think most academics know that our individual (highly specific) research projects are not easy for the public to digest, and are working on ways to present their work in a real world context. I’ve just made an animation with Oxford Sparks, about industrial biocatalysis, that explains the principles behind producing cleaner chemicals, by bringing biology and chemistry together. Hopefully, by zooming out and explaining the wider topic, you can then zoom back in on our new technology without it sounding quite so alien.

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie Flounders

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie FloundersAre there any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally do not feel that being a woman has held me back, or positively influenced my career, but equally I do respect that there are not enough women in the industry at high levels.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits. I grow up on a farm, and there was never any gender discussion, I just did what everyone else did. I remember needing to carry 50kg bags of seed from one part of the barn to the other. They were so heavy! I carried one with everyone watching, and then I started to split the bags into two, and combined them again at the other end. It never occurred to me to say that they were too heavy, or that I couldn’t do it. I just found my own way of getting it done.

In general it doesn’t just come down to being male or female. I think managers need to try harder to treat people as individuals, and manage them accordingly. Everyone has their own strengths, weaknesses and background history that you might not be aware of. People learn in different ways, think in different ways and need different things from you; to get the best from them, you have to learn to take people as they are. It might be harder for line managers, but I think it is important.

When I came to choose my supervisor for my thesis I wanted a scientist of great calibre, but also someone that I could work with and feel comfortable approaching. Kylie turned out to be a perfect match for me. She has been a fantastic role model in a lot of ways.

What has been the most rewarding part of the project?

Interacting with completely different people and knowing that something that we dreamt-up in the lab, out of pure curiosity, could actually be useful to society. That feeling is indescribable and highly addictive.

Have there been any surprises – positive or negative along the way?

There is a lot more writing involved in science than I imagined, whether it is writing academic papers, blogs or grant applications.

I am slightly dyslexic and I used to always get half marks for my spelling, which was really demoralising. I was told that I wasn’t very creative or good with words, so I came to hate Art and English. Now that I have found a subject that I want to write about, that makes me feel creative, I’ve realised that I wasn’t bad at either, I just wasn’t interested.

Did you always want to be a scientist?

I was always fascinated by how things worked on the farm. My Dad and I would take engines apart and then put them back together. I got really fixated on the fuels in cars. He could always explain the differences between car engines, but not the fuels powering them, and that spurred my interest in Chemistry.

I also had a really inspiring teacher, Mrs Chapman, I don’t think I would have gone on to study Chemistry at Oxford if it hadn’t been for her encouragement. It is really important to have a role model that believes in you.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.What are your long-term goals?

Eventually I see myself involved with running a spin-out company, and just seeing how far we can take it.

One piece of advice that you would give to other would be scientists entering the field?

Find something that you enjoy and just do it. There is no way I could put as much energy or passion into my work if I didn’t love it. Don’t be scared to push yourself – with every challenge, you learn something new.

As the much anticipated Conservation Optimism Summit begins, Scienceblog talks to Professor EJ Milner-Gulland, Tasso Laventis Professor of Biodiversity in Oxford’s Department of Zoology. Co-creator of this landmark movement, she shares how she is working to protect some of wildlife’s most endangered species, what we can all do to be more environmentally conscious and why she has had enough of the doom and gloom around nature.

What was the inspiration behind the Conservation Optimism Summit?

The idea came about when I attended a lecture given by the great coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative. That campaign has done a fantastic job of highlighting positive stories about ocean conservation, and spreading them far and wide via social media.

Highlighting the challenges we face, rather than showing the progress that is being made to tackle them, makes people feel like there is nothing that they can do to help, when it really isn’t the case.

It got me thinking about how much we conservationists shoot ourselves in the foot by focusing on the negative. Highlighting the challenges we face, rather than showing the progress that is being made to tackle them, makes people feel like there is nothing that they can do to help, when it really isn’t the case. There is a lot to be proud of in conservation, and we need to be better at sharing it.

Once I had the idea in mind, I thought about how exciting it would be to have a Conservation Optimism event linked to the Earth Day events that people like Nancy Knowlton were also planning, and about the potentially powerful effect we could have in changing the conversation within conservation.

How does the format of the summit differ from other environmental campaigns?

Conservation Optimism is intended for everyone. Environmentalists, scientists, policy makers, academics, children – people in general. Our initiative encourages a global, collaborative way of thinking. While the only professional summit, specifically for conservationists, is taking place at Dulwich College, London, there are public events taking place all over the world. The flagship Earth Optimism event is organised by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC, but there are also events in Cambridge and elsewhere, so it is possible for people to get involved anywhere. My hope is that everybody who comes along not only enjoys themselves but comes away with a renewed commitment to protecting the natural world and a set of actions that they can implement themselves to make a difference.

Image credit: EJ Milner-Gulland

Image credit: EJ Milner-GullandThe summit has been a culmination of months of planning and work, how do you plan to build on the initiative’s success in the future?

After the event we will sit down and analyse how people responded to the programme, did it inspire them or change their thinking or actions? Hopefully it will become an annual event, and more and more people around the world will get involved over time. The movement’s website will continue, and be updated with highlights from the summit and ideas to encourage people to stay connected with the Optimism movement.

What would you like the legacy of Conservation Optimism to be?

I hope conservationists will think hard about the way in which we approach our work, how we present it, and how we can be more forward-thinking and positive. We need to stop focusing on winning battles and collaborate to win the war. That begins and ends with the public working with us. We have to connect with them in a way that makes them feel that they can do something to change things.

Starting a community initiative, checking out local wildlife trust websites for news about public events, or simply replacing plastic bags with bags for life and plastic bottles for refillable ones, all helps. Plastic pollution is a huge threat to our oceans, with tragic consequences for wildlife. In all parts of the world, whether it's the UK or elsewhere, people can play a more active role in conserving their local wildlife. No matter where we live, every one of us can do more to protect the environment and get actively involved in conservation.

What’s next for you?

I’m going to Colombia in a couple of months to present at the International Congress on Conservation Biology and am looking forward to connecting with international colleagues and working how we can collaborate to tackle the challenges in our field.

What are the biggest challenges that you face in your work?

As scientists who are passionate about nature, it is challenging to make our work relevant to people's daily lives. Scientific language can be alienating; we need to bring nature to life in an exciting way that makes conservation interesting to people.

In today’s society everything we do as scientists has to have a real world impact to make it onto the agenda for governments and funders. People want to know ‘why should I care about this?’ and if we want to change the world for the better, we have to make a strong case that speaks to their needs and priorities.

Professor Milner-Gulland was inspired to start Conservation Optimism, after attending a lecture given by the coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Professor Milner-Gulland was inspired to start Conservation Optimism, after attending a lecture given by the coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative.

Image credit: ShutterstockAnd the opportunities that you enjoy the most?

For me it is the feeling that you are making a difference, changing the way people think about the natural world. I enjoy working with young people from around the world who are really passionate about conservation.

Starting a community initiative, checking out local wildlife trust websites for news about public events, or simply replacing plastic bags with bags for life and plastic bottles for refillable ones, all helps. Plastic pollution is a huge threat to our oceans, with tragic consequences for wildlife.

What achievement are you most proud of?

My ecological research in Central Asia with the saiga antelope. I’ve stuck with it for more than 25 years, through a time when uncontrolled poaching catapulted the species towards the brink of extinction,to now, when saiga numbers are increasing, and there is hope again. My research has played a part in in getting us to this point, and although it has not been without its challenges, I am very proud to have been involved.

Aside from Conservation Optimism, what other projects are you working on at the moment?

One exciting new initiative is the Oxford Martin’s School Illegal Wildlife Trade programme. The illegal and unsustainable trade in wildlife is a major threat to global biodiversity. I am working to understand the drivers and motivations of wildlife consumers to work out how we can change this behaviour.

Do you think there are any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

Balancing family time with your passion for research is a constant challenge. Fortunately, universities actively try to support people to achieve this, much more so than in many other jobs. It is important for people to realise that it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. It is possible to do well in science and have a life outside of your work.

Are there any changes that can be made to make this balance easier?

A lot of the problem comes from young people being employed on short term contracts before they achieve permanent positions, and that makes it hard to plan your life. Once you have the security of a permanent position there are lots of positive initiatives in place to support people who have family commitments. But making that step is really hard. Research grants like the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship which support people coming back into academia after a career break, are fantastic. These allow people to have research time to build their career when coming back, and make it easier to balance their various commitments.

How did you come to be a scientist?

I was raised in the British countryside, so grew up surrounded by nature and spent lots of time outdoors. I have always found biology fascinating, and was also fortunate to have a fantastic teacher who inspired me. Coming from a family who were keen to share their love and knowledge of nature with me was also an inspiration.

One piece of advice that you would give to other would be scientists entering the field?

Do what you love, rather than compromising on doing research that you feel you ought to do because it's fashionable or where the money is.

Professor Milner-Gulland pictured rowing, with her family

Professor Milner-Gulland pictured rowing, with her familyMany female scientists now have inspiring stories to tell, but all the science disciplines still need to make progress on gender equality. With the lowest percentage of female professionals of all the STEM areas (9% in UK universities), engineering is one of the most scrutinised specialisms.

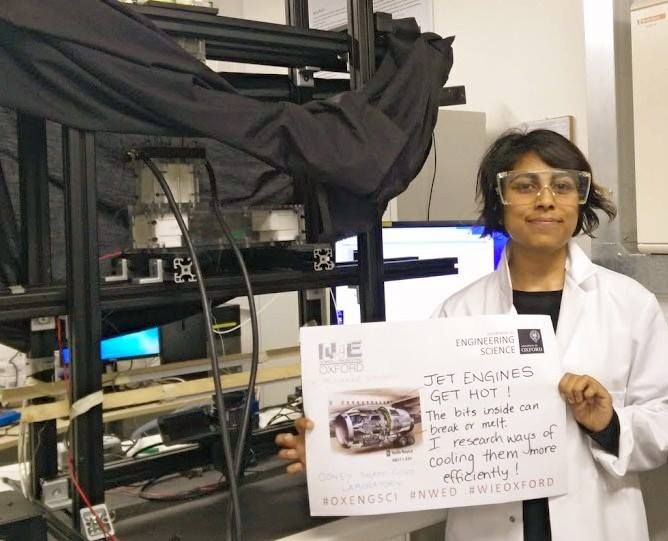

As a Canadian woman of South Asian heritage, Dr Priyanka Dhopade, Senior Research Associate at Oxford University’s Osney Thermo-Fluid Laboratory, is breaking down barriers in more ways than one. She talked to Scienceblog about her journey so far and how she is using her own experience coming from a minority background to create a brighter future for female engineers to come.

What does your work involve?

Most of my work is in partnership with Rolls-Royce plc, and focuses on the aerodynamics of jet engines, specifically controlling the temperature inside the engine. Jet engines are designed to operate at extremely high temperatures and pressures to be efficient. This means that some parts of the engine are exposed to temperatures higher than the melting points of those parts. This requires some creative cooling methods e.g. internally cooling the turbine blades using a complicated network of passages. My research focuses on finding the novel cooling methods, preventing overheating but at the same time not making it too cool that you decrease its thrust or efficiency.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer Credit: Dr Priyanka Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer Credit: Dr Priyanka DhopadeWhat is your take on diversity in general at Oxford?

I think Oxford has come a long way, but there is still more to be done. It’s a diverse and inclusive environment for research and collaboration and I work with people from various ethnicities on a daily basis. However, given the historical context, I do recognise that there is still this perception that Oxford isn't open to everyone. It can be difficult to change these perceptions and it takes time.

The Diversifying Oxford Portraits initiative is a great example of a tangible change that can help. Outreach programs targeting BME groups and communities that are outside the "Oxbridge" network can also help. The University can only benefit from diversity in all forms - ethnicity, class, gender, disability and sexual orientation. Given the current political climate, I think it's important for educational institutions, especially those as prestigious as Oxford, to set an example of an open, diverse and inclusive community.

The University can only benefit from diversity in all forms - ethnicity, class, gender, disability and sexual orientation. Given the current political climate, I think it's important for educational institutions, especially those as prestigious as Oxford, to set an example of an open, diverse and inclusive community.

What has it been like being a woman studying, working and now teaching engineering?

I have studied and worked in engineering in Canada, Australia and the UK, and the experience has been fairly similar, I have always been in a minority in my industry. After a while that gets hard to ignore. I don’t think it is so much a reflection on the universities themselves, but more to do with the level of my position within them. As my career has progressed, it has become more and more noticeable that I am in a minority in my field.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade coordinates the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, which organises talks, social events and other networking activities for women in the field.

Credit: Dr Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade coordinates the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, which organises talks, social events and other networking activities for women in the field.

Credit: Dr DhopadeHow has it become more noticeable?

As an undergraduate in Canada, I never felt or experienced discrimination. If anything, it was a very positive time for me. I worked hard to really understand the material, and helped other students along the way. When studying for my PHD I was one of the only females in the research group and now as a senior researcher I am the only female - in a group of eighty personnel. Numbers like that are hard to ignore, and you become more aware and frustrated by these issues.

I coordinate the Women in Engineering Oxford group and think I am more of a feminist and an advocate for women in STEM now, than I ever was before, because of my own journey. After a while you just start to think ‘this is not right, I should not be the only woman here.’

Do the women in the group have similar experiences?

There is real camaraderie between the women in my field, which is something I never expected. We are all tied by a common bond, and so understand the issues and support each other. I have made so many female friends across STEM and other PHD areas because of what I do, probably more than I have ever had. It's been great to watch the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, initially created to support the Athena SWAN initiative, grow over the last few years, as more women have joined the research team. Though we still have some work to do to help them progress to high level positions.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer, who works in collaboration with manufacturers like Rolls-Royce plc. Her research focuses on finding cooling methods for jet engines that strike a balance between preventing overheating and not making it so cool, that it impacts thrust and efficiency. Credit: Dr Priyanka Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer, who works in collaboration with manufacturers like Rolls-Royce plc. Her research focuses on finding cooling methods for jet engines that strike a balance between preventing overheating and not making it so cool, that it impacts thrust and efficiency. Credit: Dr Priyanka DhopadeHow do you think these issues and the general imbalance of women working in engineering can be addressed?

It has to be tackled collaboratively by employers and on a policy level. Maternity leave policies are set by the government but have a major impact on how employers view family responsibilities. I know women who have been asked in interviews, directly, if they plan to have children, and if they answer yes, they are seen as not being serious about their careers. I feel that the government sets the tone, and needs to make parental leave a shared responsibility, (as it is in Scandinavia for example). If both men and women had the option of appropriate parental leave it would be seen more as a natural progression of life for those that choose to do so, not just something that women want. I think things are moving in the right direction, but it is a long process.

Unconscious bias is a big issue that does not get much attention. It is difficult to get people to challenge and face up to their own implicit biases, everyone has them, but are rarely willing to admit to them. There is already some great training underway, like the Royal Academy of Engineering and Royal Society of Science, who are rolling out unconscious bias recruitment programmes. But more is needed to encourage panellists to be open minded, particularly at higher levels of academia.

Unconscious bias is a big issue that does not get much attention. It is difficult to get people to challenge and face up to their own implicit biases, everyone has them, but are rarely willing to admit to them.

Speaking to senior academics at Oxford, I know that the University wants to hire more women, but they just aren’t getting the applications. I’m not entirely sure why that is, but I think confidence has a lot to do with it. Having been in their shoes, without my PHD supervisor recommending me I probably wouldn’t have applied myself. There are not many women in top tier engineering research positions and for that to change there has to be some degree of head hunting for female scientists as well.

How would you describe your experience of Oxford?

I’ve been at Oxford for four, very positive years. We work closely with partner organisations, which means I get to have direct impact on Rolls-Royce plc next generation technology, which is so rewarding.

Dr Dhopade has a passion for astronomy, and in her spare time takes in some spectacular views of the moon, with her telescope from her balcony.

Dr Dhopade has a passion for astronomy, and in her spare time takes in some spectacular views of the moon, with her telescope from her balcony.

What is the biggest challenge in your job?

The biggest challenge is also the biggest blessing; working directly with sponsors. Large external organisations work to their own deadlines, so we have to adapt our working styles and be more flexible.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

In academia, continuing my research career at Oxford hopefully. My work has the potential to significantly reduce the environmental impact of civil aviation, which, as air passenger travel continues to rise, is critical. More efficient engines consume less fuel and emit less greenhouse gases. I also want to get more involved in conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.

Did you always want to be an engineer?

Growing up in a South Asian family, the cultural connotations of a career in science were very positive and encouraged, which I think isn’t always the case in the West. STEM fields were seen as stable, financially rewarding professions for boys and girls. My Dad is an engineer too, so I am lucky to have supportive parents who understand the field.

One of my earliest role models was Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman in space, and I had a signed poster of her on my wall growing up. Every time I looked at it, I’d get inspired and think; ‘if she can do it, so can I!’ Female role models play such an important role in a young girl’s life.

Engineering is mentally taxing, how do you like to unwind?

I love travelling and also have a telescope that I am always looking for an opportunity to use (even though Britain's climate is largely uncooperative in this aspect!) and so far, I've seen some spectacular views of the moon and sun from my balcony.

What is your favourite thing about your job?

Working with so many smart people is so inspiring. I feel like I am getting smarter everyday just from being around them.

Dr Dhopade is a an advocate for STEM, and involved in community outreach, conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.

Dr Dhopade is a an advocate for STEM, and involved in community outreach, conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.As Associate Professor of Organic Chemistry, a mother of two and one of Oxford University’s most successful entrepreneurs, developing both the spinout companies MuOx and OxStem, Professor Angela Russell wears many hats. She met with ScienceBlog to discuss the progress of women in science in the 21st century, her journey from academia to a successful business woman and her advice to anyone following in her footsteps.

What does your work in Organic Chemistry involve?

I run an academic research group aiming to develop new drugs to treat devastating degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and heart failure. The technologies we develop are helping us to answer fundamental clinical questions and understand how different substances affect regeneration processes in the human body. Our work is incredibly rewarding and has the potential to positively impact millions of peoples’ lives.

OxStem founders Professor Dame Kay Davies, Professor Angela Russell and Professor Steve Davies

OxStem founders Professor Dame Kay Davies, Professor Angela Russell and Professor Steve DaviesHas becoming an entrepreneur always been a goal for you?

I always thought I would be a pure academic scientist, so the business side of things was totally unexpected. Often when you make a scientific discovery the most exciting part of the project is seeing it applied, but it easy to become removed from the development process in academia, and, it got me thinking why not just do it myself?

How did your journey into science commercialisation evolve?

I have co-founded two successful Biotech companies and both evolved quite organically. Mentorship has been key. Professor Steve Davies in particular has been a huge influence on my career and a co-founder of both MuOx and OxStem. As an entrepreneur himself, he has always encouraged me down the road of the commercialisation of science.

How did you go about commercialising your research and developing a spinout company?

MuOx (Muscle Oxford) built on a longstanding collaboration with Professor Dame Kay Davies, looking for a new treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Our original findings had led to the formation of VASTOx (now Summit Therapeutics plc) who developed the drug ezutromid into clinical trials. We wanted to discover new drugs that could improve on ezutromid’s effectiveness and went back to designing new substances that took the original research to the next level; MuOx.

Often with spinout development selling your product can be a real challenge, but our ongoing relationship with Summit meant they bought us very quickly. The company was spun out in 2012 and bought for five million pounds, by Summit in 2013. We continue to run an extremely important collaborative research programme with Summit developing these new drugs for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.

The technologies we develop are helping us to understand how different substances affect regeneration processes in the human body. Our work is incredibly rewarding and has the potential to positively impact millions of peoples’ lives.

What was the biggest learning curve from the development?

Building a strong case for product development that can be easily communicated to anyone - scientists, investors and general public alike is not easy. But if you don’t get it right, you won’t get the investment. As scientists, we get used to talking to each other in scientific code, but it’s just jargon to anyone else. People can’t support or engage with something they don’t understand, so I had to learn quickly how to communicate to people with varying science knowledge, like patients and the general public. You have to build an exciting case and believe in it yourself: ‘not only is this exciting science, but we can deliver on it and change people’s lives.’ If you don’t believe in your product why should anyone else?

How did OxStem evolve?

MuOx proved that we could translate science effectively, and it gave me the confidence to go for it on a big scale with Oxstem, which was effectively MuOx 2.0. It is exactly the same premise, a company developing drugs to treat diseases. But where MuOx focused specifically on muscle degenerative disease, OxStem aims to develop a platform to treat any degenerative or age-related disease.

Was building the company very different the second time around?

Oxstem isn’t a single company, it is an umbrella company, and we spinout successful daughter subsidiaries, each with a different disease focus – four so far. As an academic research development, it has been hard and time consuming to communicate the value of this structure to university stakeholders. We had to outline the structural benefits and challenges, such as how the model could work within existing financial structures, management of intellectual property and so on. It took a long time, but we achieved our goal, and in May 2016 we hit our £17 million target needed to get the company off the ground.

Professor Russell co-founded OxStem, the company is currently working to develop a regenerative treatment that could reverse the symptoms of Alzheimer's. Photo credit: OXSTEM

Professor Russell co-founded OxStem, the company is currently working to develop a regenerative treatment that could reverse the symptoms of Alzheimer's. Photo credit: OXSTEMProfessor Russell co-founded OxStem, the company is currently working to develop a regenerative treatment that could reverse the symptoms of Alzheimer's. Photo credit: OXSTEM

What was the biggest challenge you faced setting up a spinout?

Getting people to believe in your idea in the early stages is really difficult, particularly with funders. Investment is essential to progressing opportunities from lab experiments, to something that will be of benefit to patients in the long run. It takes a lot of time and patience and you have to be up front with people, making sure that they understand what they are getting into. Yes it is a lucrative investment opportunity, but there are risks.

Professor Russell playing with her two children

Professor Russell playing with her two childrenWhat advice would you give to someone looking to commercialise their research?

Identify a clear market need for your product, make a clear development plan and a list of reasons why you are the only one that can deliver on it. That is the way to be successful. Being actively involved in progressing your research is so rewarding. If you truly believe in your idea, this is the route for you.

Generally getting government or charity funding for discovery science is straight forward, but doing so for an idea that you want to translate into a research led, spin-out is not so easy; dubbed the “valley of death”. You have to have proof of concept, and show that your idea is going to work.

What projects are you currently working on?

The bulk of my work focuses on the development of new drugs to tackle degenerative and age-related diseases. For instance in collaboration with Professor Francis Szele we are looking at treating diseases like Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions and how symptoms can be reversed. A disease like Alzheimer’s is characterised by the progressive loss of neurones in the brain, and we are working to develop a regenerative treatment that will replenish these neurones, reversing the symptoms of the condition in the process. It will make a tremendous difference to people’s lives. If all goes to plan, we will be ready to run a clinical trial in the next three to five years.

You have to build an exciting case for your product, and believe in it yourself. If you don’t believe in it why should anyone else?

Has being a woman in science posed any specific challenges for you?

I have never been discouraged or made to feel that I can’t achieve things because I am a woman. Nor have I ever felt it was an advantage either. I think that is really important. We can’t solve gender bias against women, by deflecting it to men. We have to create an environment where it is better for everybody. I am heavily involved in the Athena SWAN Charter, self-assessment process, and it’s not about creating more opportunities for women, but for everybody, and achieving equality across the board.

How do you think these opportunities can be created?

I think we have to change the working culture, and focus more on valuing people for what they contribute, not how long a day they work. In the past there was a more blinkered view that a brutally long working day was the only way to succeed, which made managing a family and a career almost impossible, but that is changing.

We can’t solve gender bias by deflecting it to men. We have to build an environment that is better for everybody. Not just creating more opportunities for women, but achieving equality across the board.

What motivated you to become a scientist?

My dad was always supportive of my ambitions. When I was 14 he told me ‘you’ll never be happy with a desk job.’ He was right. I’ve always been driven by a desire to carry out research for the betterment of human health. Chemistry was a subject I absolutely loved at school and saw as fundamental to all science because it underpins and impacts so many other disciplines, including medicine.

What advice would you give to someone embarking on a career in STEM?

The decisions that you make at the beginning of your career are important, and can impact your whole future, so try and think long term wherever possible. Everyone makes mistakes, but recognising when you aren’t on the right track and correcting it quickly makes it easier to stay on course. I came to Oxford to study Biochemistry, but realised quickly that it wasn’t for me. Two weeks before my first year exams I told my tutor I wanted to change to Chemistry. I flipped straight into the second year of a Chemistry degree, and almost gave my tutor a heart attack, but it was exactly the right decision for me.

If you hadn’t been a scientist what was your plan B?

I would have been a chef. I actually think chemists and chefs have a lot in common. They experiment with flavour combinations and we scientists cook up drugs that we want to use for clinical use. There is nothing more rewarding than cooking a nice dinner and watching your children tuck in.

In her spare time Professor Russell enjoys cooking for her family, and has found parallels between chemistry and cooking. Chefs experiment with flavour combinations, while scientists cook up drugs for clinical use. Image credit: SHUTTERSTOCK

In her spare time Professor Russell enjoys cooking for her family, and has found parallels between chemistry and cooking. Chefs experiment with flavour combinations, while scientists cook up drugs for clinical use. Image credit: SHUTTERSTOCK

In her spare time Professor Russell enjoys cooking for her family, and has found parallels between chemistry and cooking. Chefs experiment with flavour combinations, while scientists cook up drugs for clinical use. Image credit: SHUTTERSTOCK

- ‹ previous

- 2 of 4

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?