Features

In a guest blog, Prof Paul Newton of the Nuffield Department of Medicine, and Head of the Medicine Quality Group at the Infectious Diseases Data Observatory (IDDO), explains the history of falsified medicines and highlights what needs to be done to avert a problem that threatens us all.

From Vienna to the Democratic Republic of Congo, fake medicines have threatened citizens across the board – and borders – in wartime as well as peacetime.

Falsified medicines have sadly probably been with us since the first manufacture of medicines and their producers may be the world’s third oldest profession after prostitution and spying. Last year falsified ampicillin was discovered circulating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in bottles of 1,000 capsules and containing no detectable ampicillin.

The post Second World War trade of fake penicillin inspired The Third Man, a fascinating film written by Graham Greene and set in Vienna. Many of the characters, including the protagonist, fake penicillin smuggler Harry Lime, were inspired by real spies and criminals who used penicillin – both falsified and genuine – to bribe, lure and get rich in the chaos of post-war Germany and Austria. Greene later turned the script into a novel.

Unfortunately, the problem is not yet consigned to history. There are probably thousands of Third Men hidden in today’s world, for example, a Parisian who ‘manufactured’ falsified antimalarials containing laxatives, international trade in falsified medicines especially from Asia into Africa, and emergency contraceptives containing antimalarials in South America.

But falsification is not the only problem. There are also severe issues with substandard medicines, poor quality medicines produced due to negligence, sometimes gross, in the manufacturing processes, but not deliberately to defraud patients and health systems. Their consequences are also very harmful; they are likely to be under-recognised drivers of antimicrobial resistance, as they often contain less than the stated amount of active ingredient.

For both falsified and substandard medicines objective prevalence data are few and poor quality, as there has been remarkably little research or surveillance. The data are insufficient to reliably estimate the extent of the problem. Much more investment is needed to understand the epidemiology of poor quality medicines and guide interventions.

Considered a ‘miracle’ medicine, penicillin was highly effective to treat gonorrhoea and syphilis, common venereal diseases among soldiers. During the Second World War and shortly after, the drug supply was controlled by the authorities and primarily reserved for the Army, but as often happens with prohibitions, the illegal trade flourished.

Penicillin was so scarce but so sought after, as an innovative cure of many important bacterial infections, that it became a currency in post-war Europe.

The drug was also at the centre of Operation Claptrap, conducted by US Major Peter Chambers in the first years of the Cold War in Vienna. He offered genuine penicillin to Russian soldiers, in exchange for secrets and defection. It was an attractive offer, as venereal diseases were a court-martial offence in the Red Army.

Austria and France cooperated in 1946 to manufacture penicillin in the Alps to facilitate availability. In 1951, they developed the first oral version of the drug, as Penicillin V. The V referred to vertraulich, the German word for confidential.

In the 21st century, government action remains key to fighting both falsified and substandard medicines. Although there has been an enormous increase in global pharmaceutical manufacturing, there has been a grossly inadequate parallel investment in support for national medicine regulatory authorities (MRAs) in many countries. A key intervention to protect the drug supply in Low- and Middle-Income Countries will be investment in MRAs, the national keystones of medicine regulation.

IDDO works to strengthen knowledge of the scale of the problem of poor quality medicines and the most affected areas, and raise awareness among key stakeholders by sharing global expertise and collating information. The Antimalarial Quality Literature Surveyor, available through the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), is an interactive tool that visualises summaries of published reports of antimalarial medicine quality, displaying their geographical distribution across regions and over time.

The full article, ‘Fake Penicillin, The Third Man and Operation Claptrap’, can be read in the BMJ.

Researchers have charted the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and GDP, known to scientists as global 'emission intensity'.

They have discovered that global emission intensity rose in the first part of the 21st century, despite all major climate projections foreseeing a decline. The working paper by the University of Oxford describes how earlier scenarios (created in 1992 and 2000) were overly optimistic, as recently published observations show global emissions intensity rose, largely due to unexpected economic growth in China, India and Russia. While it is important to note that scenarios were not designed to accurately project individual countries, the authors show that individual countries are the 'bear traps' of global climate scenarios as they can throw projections off course.

The paper by Dr Felix Pretis and Dr Max Roser finds the highest deviations between projections and what actually happened in the observations related to central Africa, where emission intensity rises were vastly underestimated. However, African countries made up only a relatively small share of global GDP and emissions. The main forecast failure on a global scale stemmed from projections about China, where total real GDP growth over the decade was actually around 17%, yet Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios undershot this increase by 2-10%. For India, economic growth over the same period was around 10%, with IPCC scenarios showing growth up to 5% lower, and Russia's economic growth was about 6%, around 1.2-3.5% higher than the IPCC scenarios had suggested.

The authors emphasise that IPCC projections, although not forecasts per se, do not appear to be any more prone to error than alternative projections for the same time period. Creating long-term projections in an ever-changing world is challenging, and other big institutions also got it wrong, says the paper.

This study says previous scenarios commissioned by the IPCC about global emissions intensity for the period had suggested emissions would 'decouple' from economic growth and start to reduce. However, after comparing scenarios with actual observations, the researchers find 'global emissions intensity' in the first decade of the 21st century increased by 0.37% and exceeds even the closest scenario growth rate, which projected a decline of -0.1%.

Study co-author Dr Felix Pretis from the Department of Economics, co-director of the Climate Econometrics programme and James Martin Fellow at the Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School, said: 'Our results find that the unexpected growth in Asia threw the social and economic projections contained in climate scenarios. This shows how unforeseen shifts caused by boom years or climate policy in individual countries can affect the overall global projections and underlines how important the actions of a few countries can be to the overall picture on global emissions intensity.

'The IPCC scenarios assumed that countries would not be as reliant on fossil fuels for their energy as they turned out to be. The belief was also that global GDP and carbon emissions would not rise at the same rate, but for the early part of the 21st century, we see that these scenarios were overly optimistic.'

While it is understood that there will also be some uncertainties around projections of temperature changes based on the physical science in climate models, the paper underlines how over the long term, social and economic shifts are even harder to assess and are highly significant for climate change projections. Unforeseen shifts in individual countries can lead to systematic errors in scenarios at the global level, the paper concludes.

Co-author Dr Max Roser commented: 'The large span of long-run projected temperature changes in climate projections does not predominately originate from uncertainties across climate models. The wide range of different global socio-economic scenarios is what creates the high uncertainty about future climate change.'

The paper raises the question of how scenarios and forecasts should be used to guide policy in the presence of shifts and instabilities. A recent Oxford Martin School policy paper also co-authored by Dr Pretis highlights the importance of accounting for instabilities when forecasting and concludes that the discovery of such forecast failures can help correct projections. His earlier paper goes on to say that in turbulent times, policymakers may even want to switch from scenarios to forecast methods that are robust to sudden changes. This would mean creating climate mitigation goals that are explicitly linked to climate responses (such as observed warming) and cumulative emissions, rather than attempting to track particular emission scenarios.

Many of the stories on Arts Blog focus on research in the arts and humanities, but what about the students who are taking their first steps into research? In a new series, we hear the stories of some of Oxford's brilliant students.

First up is Rachel Kowalski, who started a PhD in Irish history just a few weeks ago. Professor Karen O'Brien, Head of the Humanities Division, says Rachel's story 'shows how remarkable our Humanities doctoral students are'.

'People often find their true passions later in life, but few have the courage to make sacrifices to pursue them. Since Rachel made the leap into academia, she has achieved so much in a short space of time, and she is a great role model for other people who are interested in learning later in life.'

Now over to Rachel...

Tell us a bit about your school education and why you didn’t enter higher education?

RK: I went to a very normal state school. The school was neither brilliant nor awful. I did reasonably well at school, and actually started a degree in History after my A Levels, but left after a couple of months because I felt utterly unprepared for higher education. I felt at a total loss when it came to using primary material, and was pretty poor at writing coherently.

What did you do after finishing school?

RK: After leaving my degree I got the first job I could within walking distance from my family home, because I was unable to afford to buy a car or pay to commute a long way to work. So I spent four years working for my local branch of Barclays Bank in roles including Cashier, Banking Hall Coordinator and finally as a Personal Banker. I enjoyed the role, but hated the sales pressure as I felt it led people to sell products irresponsibly in order to hit targets.

After this I managed to secure a job working for the University of Oxford in IT support for the Finance Team. I felt relieved to be out of sales, and for the first time found myself sufficiently stress free to reflect on what I wanted from life. I decided to take up studying again, part time at first, in order to achieve a degree. The plan was to spend my time as a student working out what career I wanted, and to use the degree I was setting out to obtain as a launch pad for change, for instance, by getting myself onto a graduate training scheme.

My part-time foundation certificate in Modern History, at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education gave me the necessary grounding in History, and confidence I needed to leave my full-time career in IT in order to finish my degree in just a further 2 years of full time study. I applied to a few institutions, but chose to accept my place of second year entry onto the History BA course at King's College London (KCL).

What made you decide to apply to KCL to study history at the age of 26? Was it a hard decision to make?

RK: My tutors at Continuing Education, Dr Christine Jackson and Professor Tom Buchanan, recommended Kings College London to me, when I failed my interview to get into Oxford to finish the degree full time. Whilst, as I have already said, the foundation certificate improved my writing and research skills, I was still lacking confidence in my own ability and so the interview scenario and the degree system which would have followed were not appropriate for me at the time.

My decision to leave my career, and plunge myself dramatically into debt, was a little daunting. But I felt it was worth the risk as the grades I was achieving on my foundation certificate were consistent. I am very much of the mindset that you only live once and should live the best life that you can. My education was my gift to myself, and has changed my life in ways I could never have imagined.

Do you think you worked harder as an older student than you would have done at 18?

RK: I absolutely am working harder now than I would have at 18. As a mature student I feel I have a stronger work ethic; developed through my time spent working in the private and public sectors. I also have a greater understanding of the ‘cost’ of my studies. By this I mean that I know what it will feel like to pay back to make monthly loan repayments when earning a salary. I also think my sense of pride and shame are more acute than at 18. I now quite simply could not hand in a piece of work I am not proud of. Whereas I think 18 year old Rachel just might have done.

Tell me a bit about the ‘breakthrough’ that led to your undergraduate thesis being published in a journal?

RK: The piece scored 84, and my supervisor, Professor Ian McBride [now the Carroll Professor of Irish History at Oxford University] suggested I revise it for publishing. Both he, and another academic Dr Huw Bennett, gave me feedback on the piece and helped me choose a suitable journal to apply to.

The piece was peer reviewed and accepted for publication with just minor amendments. So, really the breakthrough was simply having a supervisor who believed in me and encouraged me to push for something I never imagined would be possible for a piece of undergraduate work.

The most exciting thing about the speed with which the piece was published was the fact that I was able to footnote myself in my Masters dissertation.

What is your research proposal?

RK: I am researching the nature of the Provisional IRA campaign during the Northern Ireland ‘troubles’ between 1969 and 1979. My project will synthesise the findings of original quantitative and qualitative research in order to gain a deeper understanding of the organisations’ agenda, methods, accuracy and impact.

I am collecting new data on their daily activities, successful and unsuccessful, to disaggregate the campaign and understand the influences which shaped it. I will be considering their target discrimination policy primarily; determining who they deliberately targeted, as opposed to who was injured or died as a result of their actions.

I am learning to use GIS software to map the macro picture of my findings, and then will be moving onto conduct micro studies in a few disparate regions to establish snapshots of the PIRA’s activity and external influences in different times and places.

I will be drawing conclusions about the organisation, and extrapolating the findings to discuss the study of political violence and asymmetrical warfare more generally.

Are you working on any other projects at Oxford?

RK:I have founded a seminar series called ‘The Oxford Seminar for the Study of Violence’. It is an exciting interdisciplinary seminar series which runs fortnightly at Wolfson College. This year we are covering a wide range of topics. For instance, Dr Jelke Boesten is talking to us about Gender Based Violence in Peru; Dr David Skarbek is presenting a paper on the social mechanisms which reduce prison violence between gangs in the American prison system; and Dr Simon Prince is talking to us about the intimacy of violence in the early period of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

What do you want to do after you finish your PhD?

RK: I would very much like to stay in academia so will be looking for Post-Doctoral positions and eventually a full time academic job. It is a very competitive field, however, so am very open minded to other career paths such as research roles within my field, publishing, or teaching.

How are you financing your studies and why do you think is it important that students in the humanities have access to scholarships?

RK: I am very fortunate to have been awarded a full scholarship for my DPhil; The Wolfson Scholarship in the Humanities. The scholarship is awarded solely on the merit of the student and the quality of the research proposal submitted at application.

Scholarships are so very important in the humanities because quality research is by no means commensurate with the personal wealth of the researcher. Many students cannot afford to pursue higher education in the face of ever increasing university fees, yet alone the cost of living. Scholarships thus contribute to eroding the inequalities in our education system by supporting those who have succeeded academically regardless of whether they have received a private education, or have come from a privileged background.

I certainly would not be studying for a PhD if it were not for my scholarship. What is more, had my Wolfson scholarship not been so generous, I would not have had the time to launch my seminar series or dedicate myself fully to my studies. Rather, I would have had to resort to working part-time, as I have had to do all the way throughout my full-time undergraduate and Masters studies at Kings College London.

This post originally appeared on the Caltech website. Author: Lori Dajose.

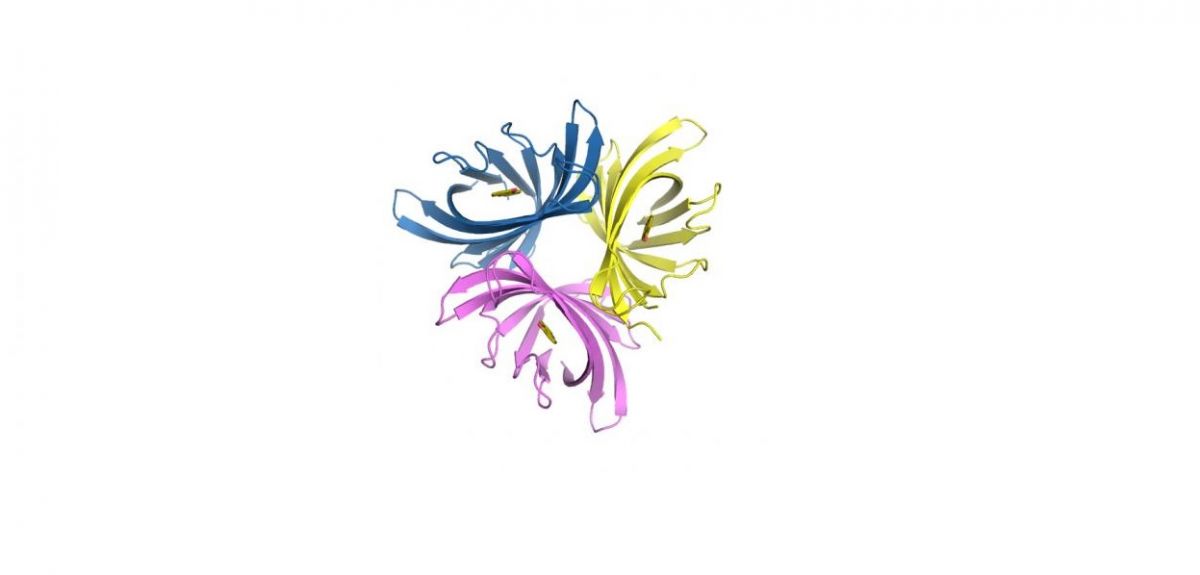

Many infectious pathogens are difficult to treat because they develop into biofilms, layers of metabolically active but slowly growing bacteria embedded in a protective layer of slime, which are inherently more resistant to antibiotics. Now, a group of researchers at Caltech and the University of Oxford have made progress in the fight against biofilms. Led by Dianne Newman, the Gordon M. Binder/Amgen Professor of Biology and Geobiology, the group identified a protein that degrades and inhibits biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the primary pathogen in cystic fibrosis (CF) infections.

The work is described in a paper in the journal Science.

'Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes chronic infections that are difficult to treat, such as those that inhabit burn wounds, diabetic ulcers, and the lungs of individuals living with cystic fibrosis,' Newman says. 'In part, the reason these infections are hard to treat is because P. aeruginosa enters a biofilm mode of growth in these contexts; biofilms tolerate conventional antibiotics much better than other modes of bacterial growth. Our research suggests a new approach to inhibiting P. aeruginosa biofilms.'

The group targeted pyocyanin, a small molecule produced by P. aeruginosa that produces a blue pigment. Pyocyanin has been used in the clinical identification of this strain for over a century, but several years ago the Newman group demonstrated that the molecule also supports biofilm growth, raising the possibility that its degradation might offer a new route to inhibit biofilm development.

To identify a factor that would selectively degrade pyocyanin, Kyle Costa, a postdoctoral scholar in biology and biological engineering, turned to a milligram of soil collected in the courtyard of the Beckman Institute on the Caltech campus. From the soil, he isolated another bacterium, Mycobacterium fortuitum, that produces a previously uncharacterised small protein called pyocyanin demethylase (PodA).

Adding PodA to growing cultures of P. aeruginosa, the team discovered, inhibits biofilm development.

'While there is precedent for the use of enzymes to treat bacterial infections, the novelty of this study lies in our observation that selectively degrading a small pigment that supports the biofilm lifestyle can inhibit biofilm expansion,' says Costa, the first author on the study. The work, Costa says, is relevant to anyone interested in manipulating microbial biofilms, which are common in natural, clinical, and industrial settings. 'There are many more pigment-producing bacteria out there in a wide variety of contexts, and our results pave the way for future studies to explore whether the targeted manipulation of analogous molecules made by different bacteria will have similar effects on other microbial populations.'

While it will take several years of experimentation to determine whether the laboratory findings can be translated to a clinical context, the work has promise for the utilisation of proteins like PodA to treat antibiotic-resistant biofilm infections, the researchers say.

'What is interesting about this result from an ecological perspective is that a potential new therapeutic approach comes from leveraging reactions catalysed by soil bacteria,' says Newman. 'These organisms likely co-evolved with the pathogen, and we may simply be harnessing strategies other microbes use to keep it in check in nature. The chemical dynamics between microorganisms are fascinating, and we have so much more to learn before we can best exploit them.'

The paper is titled 'Pyocyanin degradation by a tautomerizing demethylase inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms.' In addition to Costa and Newman, other co-authors include Caltech graduate student Nathaniel Glasser and Professor Stuart Conway of the University of Oxford. The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Science Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Molecular Observatory at the Beckman Institute at Caltech, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Sanofi-Aventis Bioengineering Research Program at Caltech.

In a guest blog, Professor Peter McCulloch from the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, explains the importance of randomised trials in deciding whether subsequent trials are necessary.

In medical science, as in all walks of life, we are impressed by dramatic effects. If a new treatment seems much better than an old one initially, there is often impatience to get on and use it, and people question why one would want to conduct formal trials.

Doctors who feel this enthusiasm for what they see as a breakthrough often argue that it’s not ethical to do a randomised trial of an exciting new treatment, because the benefits seem so obvious, and randomisation means that half the patients are deprived of them. Of course breakthroughs sometimes turn out to be false dawns, but the idea that something might be so obviously better than what we have now that it doesn’t need a randomised trial is pretty widespread in medicine.

We decided to look at this by trying to find all the published randomised trials where the new treatment was reported as being five times better than the previous treatment (or a controlled group). We thought this ‘five times better’ idea might be a useful rule for medical science. If a hazard ratio of five (i.e. the new treatment is five times better) nearly always predicted correctly that subsequent trials would always report significant benefits, then we could use this as a signpost for the point where no further evidence is needed. Unfortunately, this turned out not to be true.

We studied all of the trials in the Cochrane Collaboration Database (more than 80,000) and found that there were very few instances where there had been both trial with a dramatic effect like this and a subsequent trial. We looked at the ones we found and unfortunately the ‘five times better’ rule was wrong in over one third of the cases. In other words, even though an earlier trial showed the new treatment as five times better, a subsequent trial said it was not significantly better at all. We tried to find a rule which worked by increasing the hazard ratio or the significance of the results. We found that we had to increase the hazard ratio to 20 (i.e. the new treatment is 20 times better than the old treatment) before the rule became 100% reliable. Out of the whole Cochrane database there were only four trials that fitted this rule.

So why doesn’t this rule work? The main problem is an effect known as ‘regression to the mean’. Most of the trials that show dramatic effects are small trials, and we know that a small trial has a better chance of producing a freak result than a large trial through the effects of pure chance. Smaller randomised trials also tend to be of lower quality than larger ones and therefore open to greater degrees of bias. The implications, particularly for surgery, are quite interesting. It’s well known that it’s much harder to perform a large randomised trial in surgery than it is when studying a drug. However, our work adds to the literature showing that small randomised trials are pretty unreliable. Given that they are also very expensive and difficult to do, our results throw into question whether surgeons might be better to do another type of study in situations where they know that they won’t be able to do a large enough randomised trial to avoid the effects we are talking about. There will always be exceptions to this rule, particularly for rare diseases, but our findings could be used to support the idea that in surgery it may be useful sometimes to do a large non-randomised prospective study before committing to the major undertaking of developing a large high quality randomised trial.

The full paper ‘Very large treatment effects in randomised trials as an empirical marker to indicate whether subsequent trials are necessary: meta-epidemiological assessment’ can be read in the BMJ.

- ‹ previous

- 108 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria