Features

What do scientists, philosophers and religious leaders all have in common? The answer may surprise you, but collectively at least, they have the power to fight climate change.

At a recent special event during the 2017 European Capacity Building Initiative (ecbi) Oxford Seminar, leading voices from these three fields came together to discuss one of society’s most challenging questions: ‘what can we do to support the fight against global warming in the current political climate?’

Held at the University of Oxford, Museum of Natural History, the ‘We Meet Again!’ event was reminiscent of the renowned ‘Oxford Evolution Debate’ of 1860, and was intentionally named to draw comparison to that historic event.

Key speakers from the day share highlights and their thoughts on on how the problem can be best managed:

There is a myth that religious groups do not care about or believe in climate change - but the reality could not be further from the truth. Climate deniers exist in all walks of life and religious influencers such as myself, put a lot of effort into both educating their sects about the reality of environmental change and encouraging those involved in creating solutions to consider these communities.

It is vital that all involved in climate change negotiations understand and take seriously the different faith-based communities in the world, who are natural allies in carbon emission reduction and a more sustainable future.

Faith communities know how to take action for change and how to mobilise others to achieve common goals.

These groups are places where small groups of thoughtful and committed citizens are found. They have significant influence, a natural compassion for the earth and a sense of being part of a global community. They are not perfect, or uniform. But they are communities of hope whose values lead us to work for change, not against the findings of science, but in tandem, to bring about a more sustainable world.

The ferocity of Hurricane Harvey and Irma has many in the media and elsewhere saying that this is because of climate change, while others are saying they are nothing to do with climate change. Most scientists tend to be sitting somewhere in the middle, trying to stay true to their scientific, observational, evidence, theory and their projections for the future. Their message is ‘well neither of you are quite right’, instead giving a more nuanced message; that’s exactly what we have to do - and what we have to keep doing.

As scientists, we must continue to search for evidence-based answers and share the results of our work with a wide, diverse audience - not just our peers, opinion formers or politicians but ordinary people, without either exaggeration or understatement. We have to recognise that how these messages are received is directly influenced by the values and beliefs of the audience. For example, when confronted, some climate deniers approach the subject from a vested personal interest or political creed. Often the science is secondary to them and muddies the waters of what they want to believe.

As scientists, we must recognise that we are also influenced by our values and beliefs. We need to find common ground and a starting point for conversation. Then we must position the best science and research-led evidence at the fore-front of this climate change conversation.

Philosophers have played a role in shaping popular opinion and challenging the status quo since time immemorial. John Alexander Smith, Waynflete Professor of Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy at Oxford University, opened his 1914 undergraduate lectures with the following caveat: ‘Apart from the few who go on to become teachers or dons, nothing that you will learn in the course of your studies will be of the slightest possible use to you in life, save only this, that if you work hard and intelligently you should be able to detect when a man is talking rot..’

Philosophers have an important role to play in separating truth from nonsense. 'Alternative facts' only work if one removes objective truth from what we mean by 'fact'. Yet, "2+2 = 5" is not an 'alternative fact' of mathematics. It is simply wrong, and anyone claiming the contrary is, to quote Professor Smith: 'talking rot'.

And the same applies to climate science, where assertions are objectively true or false, and not mere subjective opinions without objectively falsifiable content. To reply: “this is your opinion” when challenged about a statement in this context, and to leave it at that, is simply not good enough.

Stressing this unequivocally is one thing philosophers can do to support the fight against global warming in today’s fragile political climate. Academic thinkers and philosophers have a duty to stand up for critical thought and the truth, to counter the current tide of ‘alternative facts’ and ‘post-truth’ politics.

As an Arctic scientist I have been travelling to the Northern Hemisphere for more than thirty years, and have seen polar melting with my own eyes. I can say with confidence that climate change is not a myth. It is very real. It is happening and it shows no signs of slowing down.

In today’s society, Arctic research is more valuable than ever. The reasons for this will vary from field to field, but climate change is currently at its most exaggerated in polar areas. For glaciologists and those interested in climate change, the Poles are therefore a rich environment to witness climate change first hand. Where as, for geologists and people in my discipline, the exposed rock is the real attraction. In the Arctic we are not hindered by vegetation. There are of course areas covered with glacial deposits, but other than that, there is just the expanse of exposed rock that you just don’t get at lower latitudes. The far north has perfect “outcrop”, as we call it.

We live in a time where the value of science is constantly being questioned and undercut, it has never been more important for us as scientists to perform our jobs well, deliver accurate research and clearly communicating the findings. The consequences of not doing so are catastrophic.

In the latest animation from Oxford Sparks, Dr Benjamin Brecht from Oxford's Department of Physics explores the 'miraculous' world of quantum physics, focusing on remarkable pieces of light known as photons.

Dr Brecht says: 'Quantum physics opens a window to a miraculous world, where extraordinary things happen that cannot be explained by our everyday experience. Things like quantum teleportation sound like science fiction, but they are being realised today in quantum laboratories. If we can harness these exciting phenomena, we can build new technologies that outperform their existing, classical counterparts. This vision of the future fascinates me and makes we want to add my small contribution to the pool of outstanding ideas.'

Oxford Sparks is a great place to explore and discover science research from the University of Oxford. Oxford Sparks aims to share the University's amazing science, support teachers to enrich their science lessons, and support researchers to get their stories out there. Follow Oxford Sparks on Twitter @OxfordSparks and on Facebook @OxSparks.

Jacinta O'Shea from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences explains how stimulation of the brains of stroke patients can cause long-lasting improvements.

Every year thousands of people are left with debilitating symptoms after stroke. Perhaps one of the most striking is known as hemispatial neglect. This is when right-sided brain damage causes people to behave as though the left half of the world does not exist.

This problem arises when damage to the right parietal cortex disrupts the connections linking visual areas at the back of the brain with motor systems towards the front. The damage leaves the stroke survivor unable to voluntarily direct attention towards, and act on, visual objects in the space to their left.

Hemispatial neglect is very common, affecting many patients in the early months after stroke. Most recover over time, but about one-third do not, and suffer neglect as a lasting disabling condition.

The orthodox approach

To date there is no clinically established treatment, although researchers are developing promising methods to improve the condition. These methods focus either on changing patients’ brain activity or changing their behaviour.

One such approach is non-invasive brain stimulation. Damage to the right side of the brain causes the (undamaged) left side to become hyperactive. Suppressive stimulation of the (undamaged) left parietal cortex can reduce this hyperactivity. By ‘rebalancing’ brain activity in this way, neglect improves, but the effect lasts only for a few minutes.

Another approach is a behavioural therapy known as ‘prism adaptation’. Patients wear glasses containing prisms, which bend light, causing objects to appear to be shifted to the right. This results in a mismatch between where a patient sees an object and where they need to move their hand in order to touch that object. With training, patients learn to adapt to the prisms, by shifting their hand-eye coordination leftwards, towards the neglected half of space. This training improves many symptoms of neglect, such as postural imbalance and reading – but the benefit usually lasts only for 24 hours after training.

If either approach is repeated daily over several weeks the improvements can last for several weeks. However, this intensive repetition is time-consuming, labour-intensive, and costly.

A novel approach

Working with colleagues at the University of Lyon, France, we investigated whether it might be possible to use brain stimulation to improve how patients learn during prism adaptation, to make the therapy more efficient. In contrast to the traditional brain stimulation approach, which involves inhibiting brain activity in the left parietal cortex, instead we excited the left sensorimotor cortex, a brain region important for retaining newly learned motor skills. We reasoned that this might strengthen memory for prism adaptation training, which could cause longer-lasting improvements in neglect.

First, we tested this idea using tDCS (trans-cranial direct current stimulation), a mild form of non-invasive brain stimulation, in healthy volunteers during prism adaptation. We discovered that exciting the left sensorimotor cortex did indeed cause long-lasting memory of the adaptation task. Having established that this worked in healthy volunteers, we then carried out longitudinal case studies with three patients with hemispatial neglect. What we found surpassed our expectations.

In the early stage after stroke, these patients had shown improvements after prism therapy. But in the ‘chronic’ stage, over one year later, although the patients still adapted to prisms, this no longer caused any improvement. In different sessions in our study the patients performed prism therapy combined with real and fake tDCS. We then tested whether each patient’s neglect symptoms changed over time. We found that just one 20-minute session of real (but not fake) stimulation during prism therapy resulted in improvements in neglect that lasted for weeks to months and did not return to the baseline.

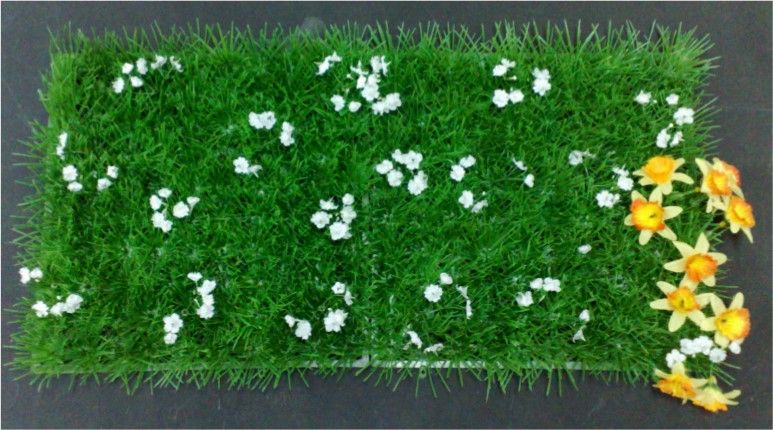

The patient was asked to distribute flowers equally around the garden. They are all clumped to the right, showing dramatic neglect of left space.

The patient was asked to distribute flowers equally around the garden. They are all clumped to the right, showing dramatic neglect of left space.Our prediction that stimulation would strengthen the memory trace formed during adaptation, and cause neglect improvements to last for a long time, was proved correct. The duration of the improvement was surprising; moreover, it appeared to be cumulative, with each combined stimulation/therapy session building on the last.

Implications for stroke recovery

For these long-term ‘treatment-resistant’ stroke patients involved in the study, this was proof that they still have the capacity to make cognitive gains. We have established, for the first time, that it is possible to ‘switch back on’ or ‘reawaken’ plasticity in dormant brain circuits of patients suffering chronic neglect, more than one year after stroke, with the therapy gains lasting much longer than expected.

We’re now testing this in a larger group of patients in a randomised controlled clinical trial using a more intensive training regime. If the findings replicate, our approach will be a nice example of how we can take ideas from the neuroscience laboratory into the clinic to help improve stroke patients’ lives.

The full paper, 'Induced sensorimotor cortex plasticity remediates chronic treatment-resistant visual neglect', can be read in eLife Sciences.

This research was funded by a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship to Jacinta O'Shea, with support from the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Words by Jacqueline Pumphrey and Dr Jacinta O'Shea, NDCN.

Most people are aware of arachnophobia, but have you heard of arithmophobia? Even if you haven’t, you’ve likely come across it.

Arithmophobia is the term for an irrational fear of numbers or mathematics – and it’s very common. So much so, that while people are usually too embarrassed to admit to finding reading or writing difficult, they feel more comfortable to laugh off their difficulty with numbers.

Dr Jennifer Rogers, Director of Oxford University Statistical Consulting of the Department of Statistics, has decided that it’s time all this changed, and is asking: ‘just what is our problem with numbers?’ As a leading statistician, she is confident that, not only is everyone capable of understanding how numbers work, but that we would be lost without them. Statistics can do so many things for you, influencing your choices without you even realising. Dr Rogers talks to Scienceblog about being a leader in her field, using statistics to improve people’s lives and why everyone is a secret statistician.

What is the one thing that you would like people to know about statistics?

I know some people find numbers scary, but they are hugely important and there for a reason. Statistics illuminate, educate and inform our decisions. They shape our everyday decisions, from choosing shampoo, to where to live, and what airline to fly with - even though we may not realise it.

How do you think public understanding of maths and statistics can be improved?

We’ve all heard the phrase ‘Lies, damned lies, and statistics’. I think many people regard statisticians as liars, manipulating data in support of whatever story or agenda suits their purpose. But, any responsible statistician just wants to discover and tell the truth and statistics allow us to do that.

Statistics help government to make important decisions, For example, they can show which area has the best crime rate or hospital response time, and where it is decreasing or increasing in others. I always maintain that everybody is a secret statistician. If you were looking to buy a house you would compare one against others in the area; how close is it to a good school? Will it improve my commute to work? That’s statistical analysis - gathering data and using it to make decisions in our everyday lives.

Knowing how to ask the right questions and recognise flaws in what you’re being told is essential if you are to get the best out of life.

Why do you think maths has such a troubling reputation socially?

I think it is a real shame that it is not a social taboo to say ‘I can’t do maths.’ A lot of people in the public eye openly admit it now, almost to the point that it’s considered cool by some. That’s really disappointing. I understand that numbers are not always intuitive. Things like percentage increases and percentage point increases can be quite complex issues for people to get their head around. Everybody’s life can be protected and illuminated through numeracy. I think everyone should be able to walk into a shop and possess the skills to not be ripped off. Or, to be able to count change when they are getting into a taxi.

It’s also important to be able to evaluate and question what you see and read in the media. Knowing how to ask the right questions and recognise any flaws in what you’re being told is essential if you are to get the best out of life. For example, when you see an article that says eating bacon is going to increase your risk of cancer by 18%, that sounds really shocking - and like you should stop eating bacon now. But as a statistician, I can see that when you get into absolute numbers, actually, eating bacon isn’t as bad for you as that headline makes it sound.

What inspired the launch of the Oxford Statistical Consultancy?

There is such a wealth of expertise within the University, but it can go unnoticed and unused by the outside world, which is such a waste. To me, it’s absolutely essential that there are accurate, properly applied statistics out there, helping us to understand more and to do things better. I’m determined that this unit will be a highly-tuned engine, powering businesses to new heights of creativity and success.

It is early days, and we have already worked with numerous and greatly diverse clients from healthcare providers to lawyers. We’ve even worked on BBC1’s Watchdog for whom we evaluated the statistical probability of getting a middle seat at random, on a Ryanair flight.

Describe a typical working day in your life?

Because statistics are involved in just about everything, as Director of the Consultancy Unit, I get to be involved in a huge range of projects. I can be working on long-range forecasting, helping a supermarket to understand the best time to stock barbeques for hot weather. I also help healthcare providers to better understand how and why a disease occurs, mapping a patient’s pathway from diagnosis through to appropriate treatments, which is especially rewarding.

I do a lot of work developing clinical trials for new treatments. I’m involved in designing the trial and deciding the best way to assess the effectiveness of treatment and I’ll also advise my clients on the most suitable method of analysis.

People often say that I don’t look like a statistician, but what does a statistician look it?

What do you like most about your role?

The mathematician John Tooki said it best: ‘statisticians get to play in everybody’s backyards’. I think that sums up my job perfectly. I’m involved in so many different, fascinating and useful things - and I love it.

What is the biggest challenge in your work?

Well, I do get frustrated when there’s a bug in some computer programming code that takes half the morning to straighten out. But, seriously, communicating statistics is both the most rewarding and challenging thing about the job.

I often work with people who are not mathematically trained. So, I may have to translate quite complex statistical ideas for those who perhaps do not understand what I’m talking about at first, and it’s wonderful to watch their faces light up as the brilliance and, in my opinion, the beauty of the numbers becomes clear to them. Being able to communicate your findings so that decisions can be made is the most important part of the job, otherwise we are just analysing data for the sake of it. For example, I may have to explain to clinicians why a new treatment is a better choice for a particular disease than other options.

What came first, your love of maths or statistics?

My maths teacher always said I was a natural mathematician, but, actually, I hated the subject at school. I thought I was rubbish at it. The standard number crunching exercises just bored me witless, but it seems to be all that’s learned about maths at school. It was only when I got to A-level maths that I really fell in love with the subject. I really began to see how statistics mattered, and the more I engaged with the figures, the more it all made sense. Plotting and playing with raw data was when the subject cast its spell on me. Ever since then I have loved applying mathematics to real world problems – and finding solutions.

What has your experience been as a woman in statistics?

Historically the field has been male dominated. People are always shocked when they meet me. They tell me ‘you don’t look like a statistician.’ But times are changing, membership of the Royal Statistical Society used to be predominantly male, but less so recently. However, I think academia is more challenging for a woman. Fixed term contracts affect decisions about starting a family. You can find yourself unemployed while on maternity leave. Job security for young researchers needs to be addressed for it to be a viable long-term career option for women. Those are just some of the issues – I could go on, but this is a great place to start.

What are you most proud of?

I am really proud that my work can help enrich people’s lives. Sometimes as a statistician you can just sit in your office and plug in the numbers, never really seeing the outcome. Having the opportunity to go and see your work in action, and understand how it is influencing change, is profoundly rewarding. I remember going to a cardiology conference where my research was used to explain an alteration to a standard medical procedure. Knowing that my work impacts real people at such critical junctures in their lives makes me feel inexpressibly proud.

As an expert on the literature of the Roman Republic and an avid viewer of the recent ITV show Love Island, Oxford classicist Dr Andrew Sillett was always going to try watching Bromans.

The new ITV programme is billed as a “gladiator reality show” which claims to send “eight modern-day lads back in time to see if they can cope with living and fighting like Roman gladiators”.

As he settled down to watch the first episode last week, Dr Sillett tweeted his reactions.

His tweets went viral – they were retweeted by dozens of other users and media outlets.

At the end of the show, he concluded: "10/10 will watch again."

“The interest my tweeting generated came as something of a surprise,” he tells Arts Blog.

“In all honesty, I didn't come to Bromans from an academic angle, it just followed on naturally from a summer spent in the company of Love Island. “All the responses I've received have been very friendly and supportive (which is hardly to be taken for granted on Twitter...).”

Andrew is evangelical about the importance of public engagement with a wide audience.

“I came to Classics from a bit of a standing start myself, as my school didn't offer Latin, Greek, Classical Civilisation or anything like that,” he says.

“Not that it was anything like Bromans that caught my interest ten years ago, that was a talk from Brasenose's Llewelyn Morgan (who bears only a passing reference to the gladiators of Bromans).

“Nonetheless I think it's undoubtedly important to be aware of what sort of contact the majority of people have with your subject.”

It is unlikely that many viewers of Bromans assumed it was a realistic depiction of Rome - but Dr Sillett says it did capture certain aspects of life in the Republic.

“In the run-up to Bromans airing I encountered a lot of snootiness in relation to the show's vulgarity, but I think that rather misses the point,” he says.

“Rome wasn't all marble, rhetoric and epic poetry, it had a popular culture of its own that was coarse, sweaty and physical.

“I think Bromans captures that as well as, say Ridley Scott's Gladiator; there's plenty ITV2 can teach us.”

Dr Sillett is a lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, specialising in the literature of the late Roman Republic and early Empire.

You can read more of his thoughts on Bromans here, and follow him on Twitter here.

- ‹ previous

- 90 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria