Features

Whether you are playing poker or haggling over a deal you might think that you can hide your true emotions.

But telltale signs can reveal that you are concealing something, and now researchers at Oxford University and Oulu University are developing software that can recognise these ‘micro-expressions’ - which could be bad news for liars.

‘Micro-expressions are very rapid facial expressions, lasting between a twenty-fifth and a third of a second, that reveal emotions people try to hide,’ Tomas Pfister of Oxford University’s Department of Engineering Science tells me.

‘They can be used for lie detection and are actively used by trained officials at US airports to detect suspicious behaviour.

‘For example, a terrorist trying to conceal a plan to commit suicide would very likely show a very short expression of intense anguish. Similarly, a business negotiator who has been proposed a suitable price for a big deal would likely show a happy micro-expression.’

Tomas is leading efforts to create software that can automatically detect these micro-expressions - something he says is particularly attractive because humans are not very good at accurately spotting them.

He explains that two characteristics of micro-expressions make them particularly challenging for a computer to recognise:

Firstly, they are involuntary: ‘How can we get human training data for our algorithm when the expressions are involuntary?’ he comments. ‘We cannot rely on actors as they cannot act out involuntary expressions.’

The second big problem is that they occur for only a fraction of a second: this means that, with normal speed cameras, they will only appear in a very limited number of frames, leaving only a small amount of data for a computer to go on.

The researchers looked to tackle the first problem by an experiment in which those taking part were induced to suppress their emotions.

‘Subjects were recorded watching 16 emotion-eliciting film clips while asked to attempt to suppress their facial expressions,’ Tomas explains.

‘They were told that experimenters are watching their face and that if their facial expression leaks and the experimenter guesses the clip they are watching correctly, they will be asked to fill in a dull 500-question survey. This induced 77 micro-expressions in 6 (now 21) subjects.’

To overcome the problem of the limited number of frames the researchers used a temporal interpolation method where each micro-expression is interpolated - essentially ‘gaps’ in the data are filled in with existing data - across a larger number of frames. This makes it possible to detect micro-expressions even with a standard camera.

Early results from the work are promising, with the automated method able to detect micro-expressions better than a human, Tomas comments:

‘The human detection accuracies reported in literature are significantly lower than our 79% accuracy. We are currently running human micro-expression recognition experiments on our data to get a directly comparable human accuracy.’

But the writing may not be on the wall for liars and con-artists just yet.

Automated recognition of micro-expressions is one thing, Tomas says, but detecting deception, and uncovering the truth, is considerably harder:

Micro-expressions should be treated only as clues that a person is hiding something, not as conclusive evidence for deception. They cannot indicate what that person is hiding or why they are attempting to conceal it.

Tomas adds: ‘That said, our initial experiments do indicate that our approach can distinguish deceptive from truthful micro-expressions, but we will need to conduct further experiments to confirm this.’

For many scientists writing about science either in their spare time or as a career can seem attractive: but what does it take to be a successful science writer?

I caught up with Penny Sarchet, a doctoral student at Oxford University’s Department of Plant Sciences, who has managed to combine her studies with writing science articles for, among others, The Guardian, The Sunday Telegraph, and New Scientist.

She recently won the Wellcome Trust/Guardian & Observer Science Writing Prize [read her article in The Observer]: I asked her about winning, her favourite stories, and what it was like to write for our very own OxSciBlog…

OxSciBlog: How did you first become interested in science writing?

Penny Sarchet: When I started my DPhil, I was surprised to find that I missed writing undergraduate tutorial essays! I really enjoyed being given a topic and being told to go off and write something good about it.

Research scientists do read and write a lot but you mainly have to focus on your (rather narrow) field and write in a very specific, scientific way. Science writing allowed me to continue my wider interest in science and gave me an outlet for writing in a more accessible, generalist way.

OSB: What did you get out of writing for OxSciBlog?

PS: I wrote articles about research in my own department (Plant Sciences). It was a great excuse to sit down with different professors I admire and ask them lots of questions! There’s some fantastic science going on in Oxford and you feel honoured when someone takes the time to explain some of it to you.

I covered fighting world hunger through crop improvement and the modern face of the historic University Herbaria, and I enjoyed helping to place a spotlight on some of the exciting work that’s being done on these.

OSB: What are your highlights from the work you’ve done so far?

PS: I’ve just won the inaugural Wellcome Trust/Guardian & Observer Science Writing Prize (professional scientists’ category), so that’s the definite highlight. Prior to that, I was really pleased to get a news story about the invasion of harlequin ladybirds into The Sunday Telegraph because I’ve been going on to everybody I know about the plight of British ladybirds for years!

Interviewing the artist Angela Palmer, who created the Ghost Forest (currently outside Oxford’s Museum of Natural History) for the Oxford magazine Phenotype was also a lot of fun too – her determination to disobey everyone who told her she couldn’t bring a collection of gigantic Ghanaian trees whole into the UK made a really great story.

OSB: What led to the choice of subject for your WT entry?

PS: I report on recent science findings for the alumnae magazine Oxford Today. I was looking for stories for last Trinity’s edition and I came across the work of Professor Irene Tracey.

She’d been using MRI scanning to look at how negative expectations can completely reduce the effectiveness of pain killers through something called the nocebo effect. I’d never heard of this flip-side of the placebo effect before.

Reading more about it, I saw that it has so many implications for health and medicine – the fact that doctor-patient trust and the power of suggestion could potentially be fatal really interested me, so I began looking for an excuse to write about it. Then I heard about the new Wellcome Trust/Guardian & Observer Science Writing Prize.

OSB: What was it like to hear you’d won?

PS: Fantastic and unexpected! I’d spent the day at a workshop at The Guardian with the other 29 shortlisted writers and they were all such interesting people with imaginative topics, so I really didn’t think I’d win.

When Dara O’Briain read out my title I had to pause to make sure in my head that it really was mine! I really enjoyed meeting so many other science journalism/writing/blogging enthusiasts and the message of the awards ceremony – that science journalism has never been so important or in-demand – was very up-beat and encouraging.

OSB: What advice would you give any budding science writers?

PS: Give it a go! You don’t know if you’re any good or if you'll enjoy it until you try. There are lots of opportunities in Oxford for students and staff to cut their teeth. It’s easy now with the internet – anyone can set up a blog and have a try.

Scientists keen to understand and preserve global biodiversity have been quietly going about a mammoth task: indexing the world’s known species.

So far the Catalogue of Life has indexed over 1,368,009 species and the latest edition features a database from Jeya Kathirithamby of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology detailing Strepsiptera, a strange order of parasitic insect.

Strepsiptera are endoparasites – they live inside their host – with almost all females spending their entire lives inside the body of other insects and males emerging as free-living adults to mate before they die, just five or six hours later.

‘The females are totally endoparasitic for their entire life history (except in one family) and all that is visible of an adult female is an extruded cephalothorax,’ Jeya tells me. ‘The female is nothing more than a “bag of eggs”, having lost all structures such as eyes, antennae, mouthparts, legs, wings and external genitalia any other insect would possess.

‘This dramatic difference between male and female makes Strepsiptera interesting model organisms for studying such aspects as mating and reproduction.’

Jeya is a world authority on these parasites where males and females can have such different lives that they even choose entirely different hosts:

‘There is a family where the males parasitize ants and the females parasitize grasshoppers, crickets or mantids. Due to the extreme sexual dimorphism and dual hosts, the sexes could not be matched until recently. We have achieved this using molecular data.’

Surprisingly, although Strepsiptera can infect and live inside the host insect for almost its entire life, the host seems unaffected and can even have its lifespan extended.

‘Strepsiptera have adapted to the life cycle of whatever host they parasitize,’ Jeya explains. ‘The comparison of the strepsipteran life cycle to the life cycles of the various hosts they parasitize is fascinating: For example the strepsipteran life cycle in a host which is a eusocial wasp is different to that of a host which is a solitary wasp and is different to that of a host which is an ant.’

Despite its unusual lifestyle this order of insect is far more than a curiosity: there are thought to be more than 600 species, with genetics revealing that individuals that look identical are in fact different species.

A recent molecular study carried out by Jeya and her collaborators found that a monotypic species in the southern states of the USA, Mesoamerica and the Neotropics revealed as many as ten cryptic species – animals which appear identical but are genetically distinct.

‘The global Strepsiptera database in the Catalogue of Life has host records and geographical distribution. These will be linked to the database of the hosts and to GenBank data. In our molecular studies, we sequence the hosts as well in order to check for contamination,’ Jeya tells me.

‘Like most Strepsiptera we find in the field the hosts are also often new to science. Here again there will be links to molecular data of the hosts. Strepsiptera parasitize seven orders of Insecta so this will be a substantial contribution.’

According to Jeya, Strepsiptera could include so many examples of cryptic speciation because of the different hosts they parasitize or their geographical distribution.

She comments that understanding the factors involved could prove very helpful in the study of a wide range of insects:

‘For instance, we are working on the phylogeny of crickets from Central America because we collected a large sample of crickets while looking for strepsipterans. Many of these crickets are new to science and at present there is no comprehensive data for crickets of Central America.

‘Both the molecular data and the geographical distribution of the cricket hosts will be linked to the database. This information will be invaluable for future researchers. Similarly, we are working on another little known host group in another area.’

Dr Jeya Kathirithamby is based at Oxford University’s Department of Zoology.

Watching a dead animal rot may not sound like everyone’s idea of fun but for insect expert Sarah Beynon it can provide a feast of information.

Sarah, from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, took part in Hippo: Nature's Wild Feast which airs tonight on Channel 4, 9pm. The programme reveals what happens to the carcass of a hippopotamus in the wild over a week, using high-tech equipment to track the vast array of predators, scavengers and insects that strip the body down to the bone.

‘The hippo is essentially a whole ecosystem to an insect,’ Sarah tells me. ‘During the decomposition process, it goes through five stages of decay; fresh, bloated, active decay, advanced decay, and remains. Each stage supports a unique suite of insects.

‘Also, the different parts of a hippo support different insects - the flesh, skin, bones and gut contents all have different species feeding on them. In fact, insects are the only creatures that will feed directly on the tough, dry skin.’

The hippo carcass studied by the team was located in Zambia's Luangwa Valley. Sarah explains that in Africa such a body may support more than 300 species of insect, with millions of individual insects calling the carcass home.

Sarah was one of the scientific team studying the carcass, her work included observing insect behaviour, collecting specimens, and then commenting on each day’s footage for the programme.

‘My personal highlights were getting up close and personal to the hippo carcass,’ she reveals. ‘I had to don a fully protective plastic boiler suit and mask to guard against potential disease, and being out in 46˚C heat (ground temperature 64˚C), it was rather warm to say the least, but well worth it to see the wealth of insect life up close and personal.

‘The metallic green hide beetles were feasting on the parched skin, whilst a host of hister beetles were preying on all other insects feeding on the carcass.’

But with such a massive meal on offer she had to be on the lookout for some of the larger diners: ‘We got stranded at night on the river bed right next to the hippo carcass surrounded by well over 200 crocodiles and 7 hyenas!

‘We got the vehicle stuck in the sand and had to dig it out in torchlight with the hyenas and crocs waiting for us to leave so they could resume their feast. Seeing so many pairs of eyes glowing in torchlight was an awe-inspiring experience.

‘In fact, every time I went filming insects, we always seemed to run into the large game at very close proximity - a herd of elephants when setting the light trap, and hyenas when searching through dung for dung beetles! Quick retreats were called for in all cases!’

Whilst the cameras recorded animals visiting the hippo day and night Sarah and the team found innovative ways to study the insects – using radio transmitters mounted on individual insects to track their movements. She believes this technology has great potential, particularly in investigating the large-scale impacts of pesticides on insect populations.

The filming may be over but Sarah is flying back with plenty of new data and specimens that could still spring some surprises: ‘All specimens taken will be identified, with the hope of finding species new to science. When I was in Zambia last year, I found a sub-species new to science, so it is very possible, as the country is so under-studied.’

Hippo: Nature's Wild Feast airs Monday 7 November 2011 on Channel 4, 9pm.

Citizen science at Oxford

Citizen science at OxfordAll publicity is good publicity, or so the saying goes, and so by all accounts I should have been pleased by the mention of our Galaxy Zoo project in the Times Higher Education a couple of weeks ago.

On closer inspection, though, there’s something really rather odd about the argument it presents, and not just in giving Galaxy Zoo, which was developed and led here at Oxford University, as an example of an American project (to be fair to THE, they printed a letter correcting this misconception in today’s edition).

The THE article divides into two sets of examples. Two examples from the past (the mathematician Ramanujan, and the discovery of fossils by Mary Anning) and one contemporary story illustrate the remarkable contribution that can be made by exceptional individuals from outside the academy. Inspirational stuff, for sure, even if, as in the case of Ramanujan and Sharon Terry, the chaplain turned biologist mentioned in the article, they were swiftly embraced by conventional institutions.

These shining, trail-blazing examples are contrasted with modern citizen science, such as Galaxy Zoo or Cornell’s amateur birdwatching projects. These, we’re told, are ‘passive’, involving only rudimentary observational activities, instead of a ‘more active and in depth approach’. I’ve dealt with similar criticism of the projects, but there’s a more interesting point here in working out how to encourage deeper engagement with modern scientific data.

The article calls for more openness, leaving the impression that us academics are keeping the data and the fruits of our labours to ourselves.

This isn’t the place to jump into the arguments for open access to journals, but in my opinion what’s missing isn’t a lack of access, but often a lack of confidence. We’ve seen with Galaxy Zoo that there is a tremendous desire to help the process of understanding the Universe - the motivation most often given by respondents to our surveys - but that doesn’t translate to a desire to be dropped head first into a sea of data, literature and jargon.

If you’re a mathematician of the calibre of Ramanujan, such a sink or swim approach will work fine, but for the rest of us some confidence building is needed. What citizen science can do is to build a series of experiences, each richer and more complicated than the last, each of which constitutes an authentic contribution to science.

As Galaxy Zoo volunteers move from classifying objects, to discussing unusual finds on our forums, to collaborating with each other and with the professional scientists on projects, they are essentially navigating an alternative to the traditional career structure. Instead of taking multiple degrees before contributing to research, they are doing something useful from the start, and as a result many more have the confidence and ability to strike out on their own.

The remarkable contribution of Galaxy Zoo volunteers has been made possible by this infrastructure. After all, the project uses almost entirely public data but significant amateur discoveries have only come through our interface, and our supportive and collaborative community.

We’re putting a lot of effort into building tools that gradually lead into this sort of free research. We have just released a paper that depends substantially on the collaboration between professionals and volunteers on the Galaxy Zoo forum. Hubble Space Telescope observations are scheduled this month to follow up on objects identified by volunteers through careful and targeted work.

Does that sound like ‘passive’ participation to you? Me neither.

Dr Chris Lintott, Principal Investigator of Galaxy Zoo, is based at Oxford University's Department of Physics.

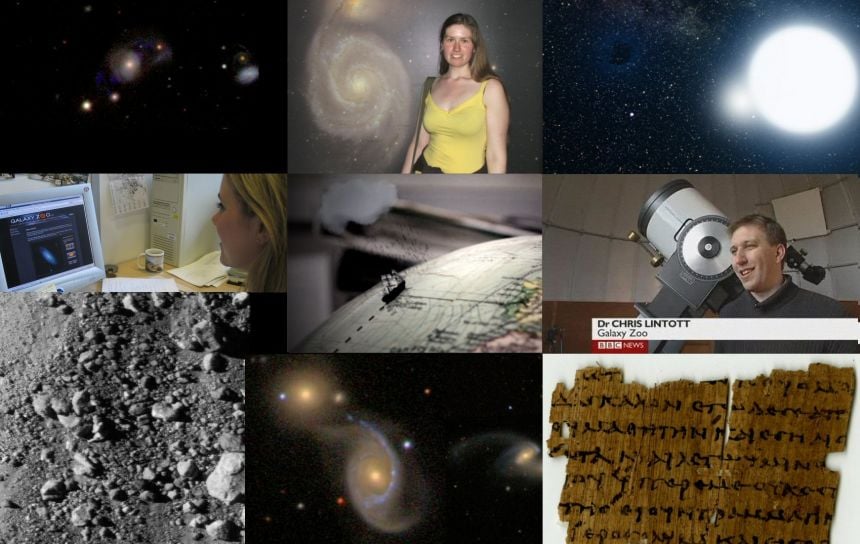

Image: highlights from Oxford-led citizen science projects [L-R] distorted galaxies from the new Galaxy Zoo paper; Hanny van Arkel, a schoolteacher who used GZ to find a new type of astronomical object; an eclipsing binary system was discovered by volunteer Carolyn Bol using planethunters.org; launch of GZ website; oldweather.org mines ship weather data; BBC Breakfast and Today interview Chris and GZ volunteers; Moon Zoo volunteers study the lunar surface; GZ Mergers searches for merging galaxies; Ancient Lives gets the public to help transcribe papyri.

- ‹ previous

- 194 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools