Features

The 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen has been marked by her face being put on the new £10 note.

But fewer people know that another prominent writer died in July 1817 – Germaine de Staël, who was arguably the most famous woman in Europe at the time.

Catriona Seth, Oxford University’s Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature, looks at the contrasting lives of the two women:

'Germaine de Staël travelled widely and her work had been translated into several languages. She was the only daughter of wealthy Swiss banker Jacques Necker, who became finance minister to Louis XVI, and was brought up in the stimulating environment of Parisian society.

She published major treatises on the influence of passions on individuals and nations, on literature and its relationship to society, not to mention on Germany (1813). She wrote on Marie Antoinette’s trial, on peace, on translation, on suicide.

Her novels Delphine (1802) and Corinne or Italy (1807) were bestsellers throughout Europe. She was also a commentator on, and historian of, the French Revolution in texts which only appeared after her death. Most periodicals felt that anything she penned, fact or fiction, political or philosophical, was worthy of a mention – whether to praise or to condemn it.

Unlike Staël’s father, George Austen encouraged his daughter Jane’s literary pursuits: he bought her notebooks for her early stories, gave her a mahogany writing desk and attempted (unsuccessfully) to get her work into print in 1797.

Jane Austen’s first published book, Sense and Sensibility, “a new novel by a lady”, which came out in 1811, bore no author’s name on its title page.

The same would go for the other novels published in her lifetime – all sold well and brought a welcome income but, to the outsider, nothing could connect them with the discreet woman who, through her richer brother’s generosity, lived with her mother and sister in a cottage on his estate.

Staël’s death in Paris was widely reported. The Monthly Magazine, before commenting at length on the funeral arrangements, opened a “Further Notice of Madame de Staël” with the following assertion:

To speak of the literary celebrity of Madame de Staël, of the elevated talent which distinguished her, of all the talent which placed her among the first writers of the age, would be to speak of all things known to all France and to all Europe … To speak of her generous opinions, her love for liberty, her confidence in the powers of intelligences and of morality, confidence which honours the soul which experiences it, would be, perhaps, in the midst of still agitated parties, to provoke ill-disposed impressions.

Staël had been reviled for her political ideas, caricatured by the gutter press for her unconventional looks and lifestyle, exiled by several regimes, and treated by Napoleon as a personal enemy, to the extent that it was said that the emperor recognised three powers in Europe: England, Russia and Madame de Staël.

When the unmarried “Miss Jane Austen” died in Winchester four days after Staël, the announcement her family (probably) wrote recalled she was the daughter of a clergyman and acknowledged that she was the author of Emma, Mansfield Park, Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility. It added:

Her manners were most gentle, her affections ardent, her candour was not to be surpassed, and she lived and died as became a humble Christian.

To this day, in the only authenticated portrait of her – a sketch by her sister Cassandra – she looks the part in her simple cap and dress, so unlike Staël’s flamboyant turban and scarlet gown.

More than “Miss Austen”, she is “Jane Austen”, someone to whom we feel we can relate. Her admirers, readers but also cinephiles who have enjoyed the adaptations, come from all the corners of the earth, are known as “Janeites”.

Many of Staël’s works have long been out of print or available only in pricey scholarly editions. She is recognised as one of the forerunners of 19th-century liberalism but does not have the common appeal and widespread recognition that time has brought to Austen.

The seeds for the “fickle fortunes” – to borrow the title of the current exhibition at Chawton House (the “Great House” lived in by her brother Edward Austen-Knight which is now home to a library of early women’s writing) – of the international literary superstardom of Austen and the waning of Staël’s fame are partly present in these obituaries.

Austen’s family cleverly crafted a reputation for demureness and devotion to both God and family as a way of deflecting from the sometimes ambiguous contemporary attitude towards women authors.

Her life was presented as quintessentially English and uneventful and her character as modest and self-effacing – in many ways the opposite of Staël’s.

In a late addition to his biographical sketch about his sister, 15 years after the death of both women, Henry Austen claimed that when invited to a party Staël was due to attend, Austen “immediately declined”.

This probably imaginary anecdote illustrates an essential reason for Austen’s success: yes, she is a great writer, but so too is Staël. Austen’s existence threatened nobody.

Staël’s championing of republican ideals, consideration of the role of emotion in politics and use of fiction to promote geopolitical and societal reflections meant her life could be discussed and her works forgotten.

Considering them jointly can help us question what shapes our canon of great writers.'

In a guest blog, Professor Thomas Adcock, Associate Professor in Oxford’s Department of Engineering and a Tutorial Fellow at St Peter’s College, discusses his newly published research ‘the waves at the Mulberry Harbours.’

Professor Adcock’s research focuses on understanding the ocean environment and how this interacts with infrastructure. He has a passionate interest in engineering history, particularly the Mulberry Harbours, which were used during the Second World War as part of Operation Overlord (the invasion of Normandy). His Grandfather was one of the engineers who worked on their design and construction.

Operation Overlord was the invasion of occupied Europe by the Allies in the Second World War. Whilst the Allies' primary enemy was the Axis forces, they also faced another foe — the weather. In particular, given the continuous necessity for personnel and supplies to cross the channel there was serious concern that the sea might cause a breakdown in supply lines. A particular problem was that the enemy would render all ports useless.

The solution to this was to construct the components of the ports in Britain and take them with them. These temporary harbours were codenamed Mulberry. The plan was ambitious — to have two harbours each twice the size of Dover Harbour — and that these should be operational only 14 days after D-Day and last for 90 days. There were to be two harbours — “Mulberry A” in the American sector and “Mulberry B” in the British sector. Various novel breakwaters and roadways were designed and constructed and floated across to Normandy in the days immediately after D-Day. The American Mulberry was finished ahead of schedule whilst the British harbour was on time.

However, a fortnight after D-Day a severe storm blew up, almost completely destroying the US harbour and doing serious damage to the British Mulberry.

Yet the British Mulberry survived and was used (after minor adaptations) for more than twice as long as originally planned. The remains of it can still be seen at Arromanches today. To an engineer a number of questions immediately spring to mind: why did one harbour fail but the other survive; and should the engineers have expected the storm that hit them?

The Mulberry Harbours interest me because they were novel and unusual structures deployed as an integral part of one of the most important operations in military history. We can gain technical insights from what worked and what failed, and learn important lessons by analysing the historical decisions that were made. But my interest is also personal. My Grandfather, Alan Adcock, was one of the engineers who made the Mulberry Harbours a reality. I doubt I would have become an engineer without his influence.

To answer the question of why the harbours had different fates we needed to understand how big the waves were which hit them. This was made possible by a wave hindcast carried out by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting.

A hindcast is similar to a weather and wave forecast — point measurements such as atmospheric pressure and wind speed and direction are assimilated into a model run on a supercomputer which predicts how strong and persistent the winds were and how big the waves would be. To model what happens in the English Channel it is necessary to model most of the Atlantic. However, as waves enter shallow water, different physics becomes important — such as wave refraction and breaking. We took the output of the large-scale hindcast and used this to drive a local model of the waves close inshore, allowing us to predict what the waves were like when they hit the harbours.

We found that the waves at the American harbour were significantly larger than those at the British Mulberry — although both experienced waves larger than they were designed to withstand. This goes a long way to explain why the American harbour failed whilst the British one narrowly survived. We also found that a storm of the severity of the 1944 storm would only be expected to occur during the summer once in every 40 years. The Allies were clearly very unlucky to experience a storm this severe only a couple of weeks after D-Day.

The lead author of our recent paper is Zoe Jackson who completed this work as part of her final year undergraduate project under my supervision. The work would not have been possible without the technical expertise of HR Wallingford and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting based in Reading.

As a final coda, this project used technical knowledge and computing power developed over the more than 70 years since D-Day, and took Zoe about eight months to complete. As I am sure my Grandfather would have observed were he still with us, this is the same period as the original engineers had to design and construct the harbours.

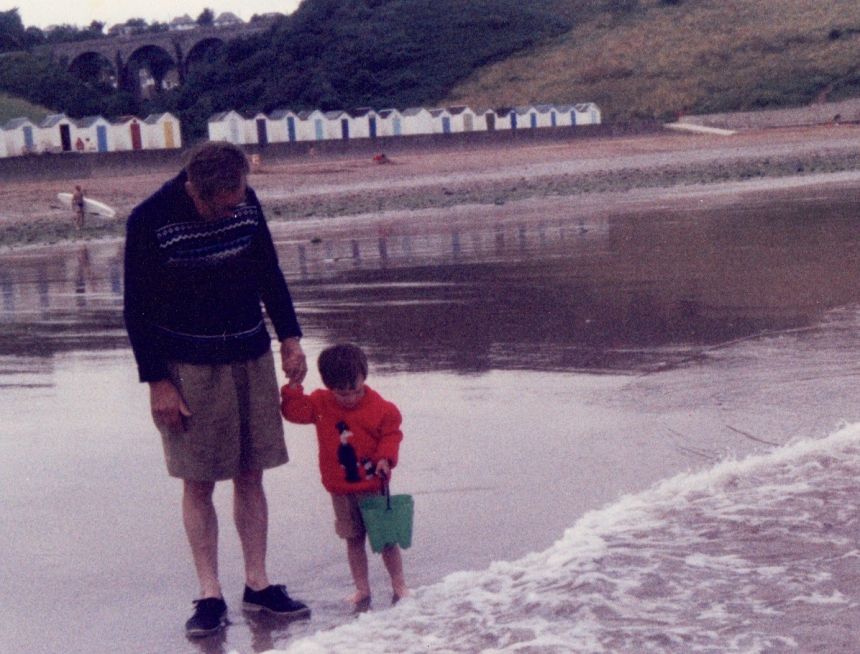

Alan Adcock giving his Grandson early lessons in coastal engineering

Alan Adcock giving his Grandson early lessons in coastal engineeringOxford Dictionaries had a surprising new entry in its most-viewed definitions pages yesterday: the word 'deuce'.

Clearly, fans watching Rafael Nadal’s marathon five-hour defeat to Gilles Muller decided to research the origin of this peculiar scoring term to calm their nerves.

The language of sport interests Oxford academics, too.

Professor Simon Horobin, of the Faculty of English Language and Literature at Oxford University, says that it comes to us from a huge variety of sources.

For instance, the rugby terms “ruck”, “maul” and “scrum” come to us, respectively, from a Scandinavian word for “haystack”, a Latin word for “hammer”, and as a modified version of the military term “skirmish”.

He says the word “tennis” itself is said to derive from medieval France, where the game first developed. Players shouted “tenez!” (“take that!”) as they hit the ball.

For those of you who turn off your TV at the sight of tennis, the meaning of ‘deuce’ is here.

Oxford Mathematician Neave O'Clery works with mathematical models to describe the processes behind industrial diversification and economic growth. Here she discusses her work in Oxford and previously at Harvard to explain how network science can help us understand why some cities thrive and grow, and others decline, and how they can offer useful, practical tools for policy-makers looking for the formula for success.

No man is an island. English poet John Donne's words have new meaning in a 21st century context as network and peer effects, often amplified by modern technologies, have been acknowledged as central to understanding human behaviour and development. Network analysis provides a uniquely powerful tool to describe and quantify complex systems, whose dynamics depend not on individual agents but on the underlying interconnection structure. My work focuses on the development of network-based policy tools to describe the economic processes underlying the growth of cities.

Urban centres draw a diverse range of people, attracted by opportunity, amenities, and the energy of crowds. Yet, while benefiting from density and proximity of people, cities also suffer from issues surrounding crime, transport, housing, and education. Fuelled by rapid urbanisation and pressing policy concerns, an unparalleled inter-disciplinary research agenda has emerged that spans the humanities, social and physical sciences. From a quantitative perspective, this agenda embraces the new wave of data emerging from both the private and public sector, and its promise to deliver new insights and transformative detail on how society functions today. The novel application of tools from mathematics, combined with high resolution data, to study social, economic and physical systems transcends traditional domain boundaries and provides opportunities for a uniquely multi-disciplinary and high impact research agenda.

One particular strand of research concerns the fundamental question: how do cities move into new economic activities, providing opportunities for citizens and generating inclusive growth? Cities are naturally constrained by their current resources, and the proximity of their current capabilities to new opportunities. This simple fact gives rise to a notion of path dependence: cities move into new activities that are similar to what they currently produce. In order to describe the similarities between industries, we construct a network model where nodes represent industries and edges represent capability overlap. The capability overlap for industry pairs may be empirically estimated by counting worker transitions between industries. Intuitively, if many workers switch jobs between a pair of industries, then it is likely that these industries share a high degree of know-how.

This network can be seen as modelling the opportunity landscape of cities: where a particular city is located in this network (i.e., its industries) will determine its future diversification potential. In other words, a city has the skills and know-how to move into neighbouring nodes. A city located in a central well connected region has many options, but one with only few peripheral industries has limited opportunities.

Such models aid policy-makers, planners and investors by providing detailed predictions of what types of new activities are likely to be successful in a particular place, information that typically cannot be gleaned from standard economic models. Metrics derived from such networks are in-formative about a range of associated questions concerning the overall growth of formal employment and the optimal size of urban commuting zones.

OXFORD MATHEMATICS PUBLIC LECTURES - THE MATHS OF NETWORKS:

Oxford researchers have found that human ancestors were able to cope with changes in their environment as the climate varied. They developed a new method to measure climate in Africa millions of years ago, using an unexpected source: the fossilised teeth of large mammals.

Hominins lived in Africa from about 7 million years ago, and were the ancestors of all present-day human beings. It’s thought that they evolved many of the distinctive features of modern people, such as sweating and walking upright, but we don’t know exactly what drove these changes. The new research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, investigated whether climate change could have been a factor.

We know that the African landscape was transformed by the spread of tropical grasses, but it’s a challenge to work out why this happened, and how climate change might have affected the evolution of hominins. Obviously, rain doesn’t fossilise, and while some indicators of an arid environment are preserved, they’re very sensitive to other factors which make them difficult to use.

The Oxford team looked at a single area, near Lake Turkana in northern Kenya, where sediments preserve fossilised hominins, as well as evidence of their behaviour such as stone tools. They analysed the teeth of herbivores, including the ancestors of present-day giraffes and hippopotamuses, from the same areas where hominin fossils and tools have been found and ranging in age from about four million to ten thousand years old.

The method is based on correlating oxygen isotope ratios in modern animal teeth and water with climate data at more than 30 sites in eastern and central Africa. In an arid environment, a lot of water evaporates from the ground, leaving behind more of a type of “heavy” oxygen, oxygen-18, relative to the common “light” oxygen, oxygen-16. When animals eat and drink, the ratio of heavy to light oxygen in food and water enters their bodies and is ultimately deposited in their teeth. By measuring oxygen isotope ratios in fossilised teeth, the researchers could determine how arid it was in the past.

They found that hominins were able to survive in both humid and arid environments in eastern Africa. This supports the idea that some of the ways humans changed as they evolved might have helped them to cope with climatic change.

Dr Scott Blumenthal, of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology at Oxford University, said “Researchers have long assumed that a long-term drying trend caused hominin environments to become more open. It was thought that this was what drove many of the fundamental changes in human evolution. We didn’t find evidence for a long-term trend like this. We found that the climate has varied over time from arid to humid, similar to the range of environments you find in eastern Africa today. It may be that this variability of climate was more important in driving evolutionary changes.”

- ‹ previous

- 94 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria