Features

Celebrations are beginning for the 200th anniversary of the birth of computer visionary Ada Lovelace in December.

In an article published in 1843, Ada Lovelace imagined a future in which programmable machines would be essential to the progress of science, and might even be used to create art and music.

Many of her letters are stored in the Bodleian Library and now being heard for the first time on BBC Radio 4, voiced by Oscar-nominated actress Sally Hawkins. The first episode of the two-part series is out now.

The Bodleian Library is running a display from 13 October to 18 December which will allow visitors to see Ada's exercise books, childhood letters, correspondence with Charles Babbage, a newly found daguerreotype, and a new archive discovery showing computational thinking in action – Lovelace, Babbage, magic squares and networks.

A symposium held at the Mathematical Institute, led by the Department of Computer Science and supported by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities will present her life and work and contemporary thinking on computing and artificial intelligence, on 9 and 10 December.

Ada, Countess of Lovelace (1815–1852), is best known for a remarkable article about Charles Babbage’s unbuilt computer, the Analytical Engine. This presented the first documented computer program, to calculate the Bernoulli numbers, and explained the ideas underlying Babbage’s machine – and every one of the billions of computers and computer programs in use today.

Going beyond Babbage's ideas of computers as manipulating numbers, Lovelace also wrote about their creative possibilities and limits: her contribution was highlighted in one of Alan Turing’s most famous papers 'Can a machine think?' Lovelace had wide scientific and intellectual interests and studied with scientist Mary Somerville, and with Augustus De Morgan, a leading mathematician and pioneer in logic and algebra.

Oxford's celebration is led by the Bodleian Libraries and the University of Oxford’s Department of Computer Science, working with colleagues in the Mathematics Institute, Oxford e-Research Centre, Balliol College, Somerville College, the Department of English and TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

A programme run by Oxford University Museums in partnership with experts from the Said Business School aims to teach cultural organisations to be more entrepreneurial.

The Oxford Cultural Leaders programme was held for the first time in March 2015, bringing together a group of leaders to experiment and take risks with new business models and to explore new ways of working and creating organisational cultures that encourage new ideas. The next programme will take place in April 2016.

The programme makes use of the University's expertise in museums and in business studies and is led by experts including Pegram Harrison and Keith Ruddle of the Said Business School and Diane Lees, director general of the Imperial War Museum.

Lucy Shaw, director of Oxford Cultural Leaders, said: 'The programme was created in response to the clear message from governments across the globe that cultural organisations need to look beyond the state for their income, demonstrating their commercial acumen and ability to deliver successfully new business models.

'Oxford Cultural Leaders addresses the need for cultural organisations to reinvent themselves as businesses, albeit not-for-profit, with entrepreneurial ways of thinking and behaving, by developing a cadre of leaders who are able to skilfully and confidently tackle these challenges.'

Tracey Camilleri, director of the Oxford Strategic Leadership Programme at the Saïd Business School, said: 'Future leaders in the cultural sector will need to develop the confidence to think about their organisations as sustainable entities.

'This will require new skills and approaches – some learned from different sectors and disciplines. The Oxford Cultural Leaders Programme in my view provides a powerful platform for the development of this shared future.'

Rachel Hudson, director of marketing, communications and development at the Shakespeare Birthday Trust, attended Oxford Cultural Leaders last year. She said: 'Some of the sessions on the programme had a trick or a technique you could take back and instantly use, which has been great and immediately useful.

'But the sum of the sessions coming together to explore adaptive leadership has had the most impact on me. The programme has made me feel more considered about my career, my professional practice and my leadership style.'

Participants will stay at Trinity College, Oxford.

What did ancient words spoken in Europe and Asia over 6,000 years ago sound like?

A project at Oxford University is using scientific methods to answer this question.

'Since the 19th century, historical linguists have tackled this question by studying the forms of words in many languages at different points in history, using that knowledge to infer the forms of words from a time before writing,' says Professor John Coleman, Principal Investigator of the Ancient Sounds project, which is based in the Phonetics Laboratory, part of Oxford's Faculty of Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics.

'We are taking a revolutionary new approach, which combines acoustic phonetics, statistics and comparative philology.

'Rather than reconstructing written forms of ancient words, we are developing methods to triangulate backwards from contemporary audio recordings of simple words in modern Indo-European languages to regenerate audible spoken forms from earlier points in the evolutionary tree.'

In 2013 the project reconstructed the pronunciation of spoken Latin words for numbers. This year Professor Coleman has a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) to extend this work to Germanic languages like English, German dialects and Dutch, as well as Modern Greek.

For example, the English word 'three' comes from Proto-Indo-European word 'treyes', a word rather like the Spanish 'tres'. This sound file shows the possible linguistic development of the word.

The English 'two' comes from Proto-Indo-European 'dwoh', as illustrated in this sound file.

The project is also investigating questions like: How far back in time can extrapolation from contemporary recordings progress? How “wide” and diverse must a language family tree be in order to triangulate to sounds that are plausible i.e. reasonably consistent with written forms from antiquity? Do sound changes proceed at a uniform, gradual rate?

Professor Coleman spoke about his project yesterday (7 September) at the British Science Festival in Bradford and will present at the Oxford University Alumni Weekend later in the month.

Readers can follow the project’s updates on the Ancient Sounds website and Twitter feed.

Ancient Sounds is run in collaboration with the Statistical Laboratory at the University of Cambridge.

From deadly pandemic to asteroid strike, most of us can name a few ways the world might end. The end of the world as we know it fuels Hollywood plots and bestsellers. But is this a modern phenomenon?

Dr Daron Burrows, of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, has launched a new project, The Apocalypse in Oxford, to digitise a collection of medieval texts which suggest the apocalypse has been in fashion for much longer than you might think.

'There was something of a vogue for illustrated manuscripts of the Revelation – the Biblical Apocalypse - in the 13th century,' says Dr Burrows. 'There were at least 80 produced between the 13th and 15th centuries, of which around half originated in Britain.'

The Bodleian Library currently holds five different Anglo-Norman copies of the French Prose Apocalypse, vividly illustrated with beasts, angels and other scenes from the Book of Revelation. Dr Burrows will scan and transcribe the books, which will then be made available to the public online.

'There are two main factors in the popularity of these books,' said Dr Burrows. 'In the 12th century, Joachim of Fiore, a Calabrian abbot, wrote a gloss on the Book of Revelation which seemed to indicate that the world would end in 1260, and later commentators thought the Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe confirmed his interpretation. This may have sparked some popular interest in the Apocalypse.

'But perhaps the more significant factor is that these books were very expensive luxury items. As far as we know about their provenance, the majority were commissioned and owned by noble families rather than, for example, religious institutions. These families may well have owned an Apocalypse manuscript less for its moral or spiritual lessons than to manifest their wealth and prestige.'

Despite their origins in the British Isles, the five books which Dr Burrows will digitise are written in French. They include a translation of the Book of Revelation, and a commentary whose origins are not yet clear.

'After the Norman Conquest, French became the language of power and authority in Britain,' said Dr Burrows. 'All administration was carried out in French, the English aristocracy quickly began to use it, and it became the language of literature.

'Perhaps paradoxically, French was used less frequently in material written in France itself during this period: indeed, two-thirds of all surviving 12th-century manuscripts of French literature originated in Britain.'

The form of French which was used in the British Isles was mainly influenced by the Norman dialect which William the Conqueror brought with him, but Anglo-Norman also features traits from the other regions from which the Conqueror's troops were drawn.

It was also modified by the accents of British speakers. However, it can be difficult for philologists to distinguish between different dialects in written text, because spelling was not standardised.

'When texts are written in verse, the rhymes can often provide clues regarding the dialect in which the poem was originally written,' said Dr Burrows. 'Since there was no standardised orthography, scribes copying a text would commonly change spellings to match their own regional conventions.

'Changing the sounds at the rhyme, however, would require more drastic changes, and so rhymes often preserve the phonology of the original text.'

For example, in medieval Continental French, as in modern French, it would be impossible to rhyme nul and seul, but in Anglo-Norman, the assimilation of sounds makes this a common rhyme.

Such comparisons allow philologists to state with some certainty whether a text originates from France or from Britain. However, the five Apocalypses in the Bodleian are all in prose. As part of the project, Dr Burrows will analyse the texts in detail, aiming to shed light on their provenance.

A traditional method of farming often praised for being environmentally sustainable actually releases 'significant' greenhouse gas emissions, an Oxford University study has found.

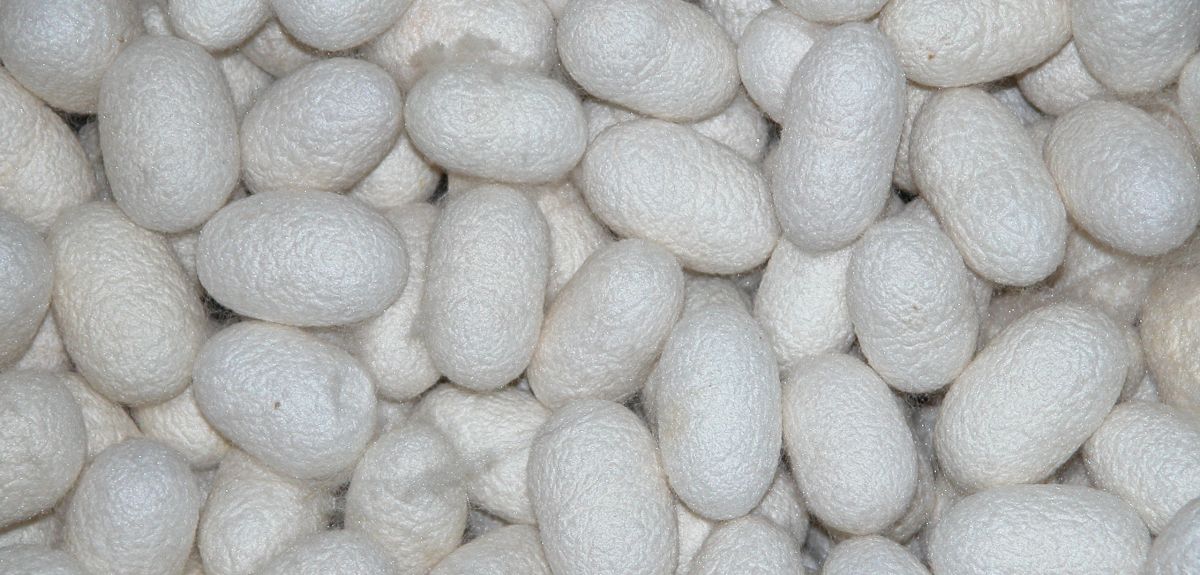

Integrated fish farming is common in aquaculture and a particular system from southern China combining silk production and aquaculture has been regarded as a prime example of multi-functional agriculture with a 'closed-loop' recycling process.

Organic residues from silk production are added to ponds to encourage the growth of phytoplankton, feeding fish. Waste accumulated in the pond sediments is removed and used to fertilise mulberry, which is in turn fed to silkworms.

A team led by Professor Fritz Vollrath of the Oxford Silk Group analysed the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions. Their results are to be published in the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment.

'We have found that the formation of methane in pond sediments can be a significant source of emissions blamed for global warming,' said Professor Vollrath.

'Until now this method of small-scale farming has been held up as a shining example of environmentally-friendly farming. But our results suggest it may make an appreciable and previously underestimated contribution to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.'

He added: 'The effect is significant because carp are the most heavily farmed fish in the world, and commonly raised in fertilised ponds.'

- ‹ previous

- 145 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria