Features

This year is the 100-year anniversary of the death of Henry ‘Harry’ Moseley, a promising English physicist who died in Gallipoli in World War One in 1915, aged only 27.

His work on the X-ray spectra of the elements provided a new foundation for the Periodic Table and contributed to the development of the nuclear model of the atom.

He had been tipped for one of the 1916 Nobel Prizes and when he died, newspapers on all sides of the conflict denounced his death. One English newspaper declared he was “too valuable to die”.

To mark this anniversary, TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities and the Museum of the History of Science have co-organised a discussion on this question tomorrow evening (13 October).

Taking part in the discussion will be Silke Ackermann, director of the Museum of the History of Science; Liz Bruton, co-curator of the ‘Dear Harry’ exhibition into Henry Moseley’s life, and Nigel Biggar, Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford.

Professor Biggar has given Arts Blog a preview of his argument.

'In one sense, scientists are not special: surely every individual is too valuable to die. More exactly, unless we think along pacifist lines, scientists along with everyone else might have a moral duty to risk their lives in war for a just cause.

'Indeed some scientists might prefer not to be privileged with a special, safer status: for example, the future socialist economic historian, R. H. Tawney, deliberately chose to fight in the ranks as a non-commissioned officer.

'What's more, scientists ought not to pretend that somehow their academic calling exempts them - like medieval clergy or religious Jews - from the demands of political duty that fall on every citizen.

'If we think that Britain's fighting at all in WWI was just a dreadful mistake, then Moseley's death (like every other death) at Gallipoli was a tragic waste; but I suggest that Britain's belligerence as a whole was not a mistake, even if parts of it (like Gallipoli) were.

'All that said, however, there are of course very good pragmatic reasons why a country at war should exempt certain classes of citizen from front-line service--whether to play alternative important roles in the war effort, or whether to preserve cultural stock for the peace: maybe Henry Moseley should have been one of them.'

Tickets for the event are free, and can be booked online here. This is part of the programme of events for the centenary exhibition, 'Dear Harry...' - Henry Moseley: A Scientist Lost to War, staged by the Museum of the History of Science with support from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) which has been now been extended until 31 January 2016 due to popular demand.

If you aren't a sports fan, the language of sport might seem inescapable.

Either the ball’s in your court and you’ve got into the full swing, or else you’re about to throw in the towel and have to hope you’ll be saved by the bell. Sports jargon and idioms permeate the way we use English.

Professor Simon Horobin, of the Faculty of English Language and Literature at Oxford University, reveals that the language of sport comes to us from a huge variety of sources. For instance, the rugby terms “ruck”, “maul” and “scrum” come to us, respectively, from a Scandinavian word for “haystack”, a Latin word for “hammer”, and as a modified version of the military term “skirmish”.

The diverse origins of sporting terms reflect the wide range of languages which have influenced English vocabulary. ‘Sporting lexicons are like the English language in miniature,’ said Professor Horobin.

Some sporting terms reflect their international context. Cricket is popular round the world, particularly in Commonwealth countries, and the terminology has developed accordingly. The “doosra”, for instance, is a bowling technique which takes its name from the Hindi word meaning “other (one)”.

Perhaps more unexpectedly, the word “tennis” itself is said to derive from medieval France, where the game first developed. Players shouted “tenez!” (“take that!”) as they hit the ball.

Even in English-speaking countries, the regional differences can be surprising. In Britain, the difference between “rugby” and “football” is obvious. But one was originally known as “Rugby football”, named after the public school where the sport was invented, while the other became known as “association football”, perhaps to resolve the ambiguity.

“Association football” gave rise to the term “soccer”, which is used in the USA to distinguish it from American football – which itself developed from rugby.

Confusing. But one of the things Professor Horobin is particularly interested in is how slang and language conventions in sport separate “true fans” from the uninitiated: 'In British usage, you only need to hear someone say the score in a football match is “zero-zero” to know they aren't a true fan, since it should be nil-nil, or love-all if it's tennis or squash.'

Those who don’t follow football but watch matches during a World Cup will know this only too well.

“Nil”, incidentally, derives from the Latin “nihil”, meaning “nothing”. “Love”, meanwhile, is said to derive from the French “l’oeuf”, meaning “egg” – the shape of the numeral zero.

'I'm also interested in the way sporting terms and phrases have infiltrated non-sporting contexts, said Professor Horobin. Cricket is a good example. Since it's associated with fair play, we talk about “playing with a straight bat” to mean “behaving honestly and decently”, and it's “just not cricket” to refer to any behaviour that flouts common standards of fairness.'

Professor Horobin has discussed sports etymology on the BBC World Service Sportshour programme in the last few weeks. He also blogs about word origins on Oxford University Press' Oxford Dictionaries site.

200 years ago William Smith published the first geological map of England and Wales. A new exhibition at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History tells the story of the life of Smith, the 'father of geology'.

The exhibition is called 'Handwritten in Stone: How William Smith and his maps changed geology', and runs from this Friday (9 October) to 31 January 2016.

The Museum holds the largest archive of Smith material in the world and many of its treasures will be shown in the exhibition. The map will be shown alongside Smith’s personal papers, drawings, publications and other maps, in addition to fossil material from the Museum's collections.

Visitors can also see the oldest geological map in the world – a map of Bath drawn in 1799 by Smith.

Smith was born in Oxfordshire and he conceived his geological theories and created maps single-handedly. His story was made famous with the publication of Simon Winchester's 'The Map that Changed the World' in 2001. Mr Winchester will give a talk at the Museum on Tuesday 13 October. Tickets can be booked here.

Smith's approach to mapping remains in use today. On 3 November, Oxford's Professor of Earth Sciences Mike Searle will give a lecture at the Museum on how he himself has used Smith's techniques to map the Himalaya, combining it with modern techniques.

The exhibition was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Tom Stoppard, Simon Schama, Stephen Greenblatt, the Assad Brothers and Christian Thielmann have been announced as Humanitas Visiting Professors at Oxford University over the next academic year.

This month, Professor Stephen Greenblatt will give two public lectures in Oxford as Humanitas Visiting Professor of Museums, Galleries and Libraries.

In Hilary Term next year Christian Thiemann will be Visiting Professor for Opera Studies and Tom Stoppard will be Visiting Professor for Drama Studies. In Trinity Term the Assad Brothers will share the Visiting Professorships for Classical Music and Simon Schama will lecture as Visiting Professor for Historiography.

Professor Greenblatt will speak on the theme of 'The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve' in the Weston Library's Blackwell Hall on 19 October and the South School of the Examination Schools on 20 October.

He will also lead a graduate seminar in the lecture theatre of the Weston Library on 21 October.

Stephen Greenblatt is Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. He is the author of twelve books, including The Swerve: How the World Became Modern and Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare.

His honours include the 2012 Pulitzer Prize and the 2011 National Book Award for The Swerve, the William Shakespeare Award for Classical Theatre, and two Guggenheim Fellowships.

Professor Greenblatt's visit has been organised by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, the English Faculty, and the Bodleian Library.

Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities.

Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Weidenfeld-Hoffmann Trust with the support of a series of benefactors and administered by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

It can take botanists decades to accurately classify plants after they’ve collected and stored away samples from the wild. But now Oxford University researchers have developed a technique to streamline the process — and it’s already unearthing new species around the world.

In 2010, researchers from the Department of Plant Sciences, led by Dr Robert Scotland, published a paper that investigated how long it takes for plants to be described after they’ve been collected in the wild. The results came as a surprise: it turned out that just 14 percent of specimens were classified within five years, and on average it took 35 years for specimens to be recognised and classified as ‘new’. ‘People might imagine that researchers venture into the wild, point at something and say “that’s new”,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘But it doesn’t work like that: mostly they get added to collections, then they're discovered at a later date.’

All the while, then, collected flowers sit dried and mounted on cardboard and placed in storage at herbaria for safekeeping. From their figures, the team estimated that of the 70,000 species of flowering plants thought to remain un-described, up to half may in fact sit in collections awaiting identification. Given the rate of discovery currently averages around 2,000 plant species per year, the team vowed to investigate whether there may be a way to expedite the process.

Generally, botanists perform one of two studies to describe plants in a given genus. The first, known as the Flora approach, is performed in a limited timeframe and describes all plant species in a particular country or region, using short descriptions and simple illustrations with no assessment of genetic differences taken into account. The second, referred to as the Monograph approach, takes a global view of all the species in a given genus, accurately demarcating each species and providing long descriptions, genetic analyses and detailed illustrations.

The latter is considered the gold standard in botanical taxonomy, not least because it provides a reliable means of identifying redundancies in existing classifications. But it often takes a long time to perform and involves intensive study. ‘It would be lovely to monograph the whole world, but that’s a pipe-dream,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘Especially in the tropics, where there are too many plants, written about in too many places, often in too many different languages, with too much redundancy in existing names. The size of the task is just too big.’

Instead, the team thought there could be middle-ground between the two approaches. ‘We wondered if we might be able to combine some of the speed of a Flora approach with some of the rigour of a Monograph,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘And we’ve ended up with what we call “foundation monographs”.’ The new approach combines the time-limited approach and short descriptions of the Flora approach with the genetic analyses and fieldwork of Monographs, enabling species to be uncovered quickly, but accurately. Crucially, it borrows content like drawings and genetic analyses, where they exist, from existing studies, in order to avoid duplicating work.

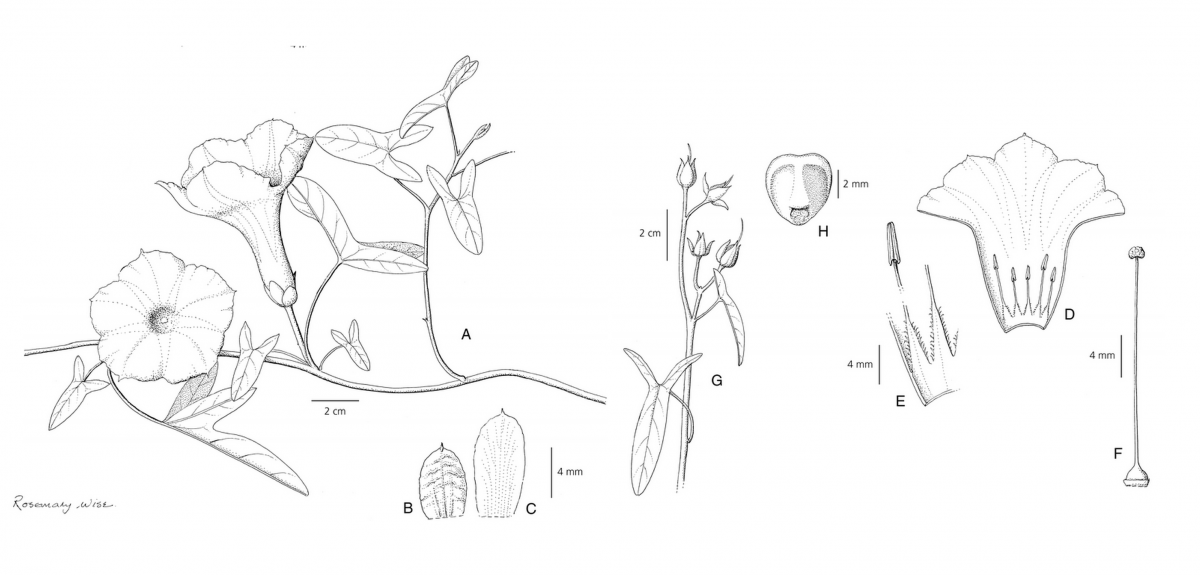

With a year of funding from Research Councils UK’s Syntax program, Dr Scotland’s team performed a one-year pilot study to create a foundation monograph for Convovulus (bindweed) — the first ever global study of the genus. It worked well: in 12 months, they recognised 190 species, including 4 new ones. ‘We showed that we’re able to catch the species that have slipped through the net in the past,’ explains Dr Scotland.

That was enough to help them secure a larger grant from the Leverhulme Trust to perform a three-year study of the Ipomoea (morning glories) genus — of which sweet potato is a member. Taking 1,500 samples from around the world, they sequenced DNA from the samples to identify key genes that can be used to create the genetic family tree of the species. Using those data, they were able to refute or corroborate existing species concepts, in the process identifying 18 new species and confirming the existence of 102 separate species in the genus from a single country, with many more to follow from other areas. From there, they were able to photograph and create detailed line drawings for those newly discovered species, finally publishing the foundation monographs in Kew Bulletin this September.

As far as Dr Scotland is concerned, we’re likely to see more species being identified like this in the future. “We’re probably seeing the end of the traditional approach to botanical taxonomy,” explains Dr Scotland.“That’s why we’re trying to do taxonomy in a time-efficient, clever way, at a scale that’s truly impressive.”

The most recent paper, entitled ‘Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Bolivia’ is published in Kew Bulletin. The Convolvulus monograph, entitled ‘A foundation monograph of Convolvulus L. (Convolvulaceae)’, is published in Phytokeys. The illustrations for the research were funded by an NERC IAA award.

- ‹ previous

- 143 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria