Features

Many female scientists now have inspiring stories to tell, but all the science disciplines still need to make progress on gender equality. With the lowest percentage of female professionals of all the STEM areas (9% in UK universities), engineering is one of the most scrutinised specialisms.

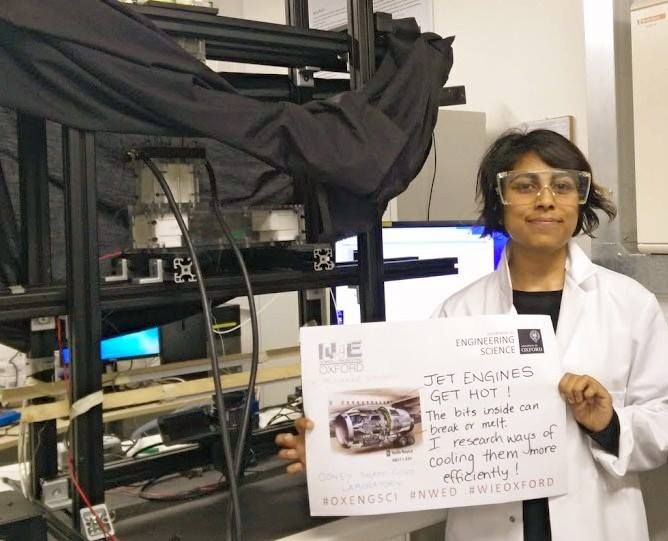

As a Canadian woman of South Asian heritage, Dr Priyanka Dhopade, Senior Research Associate at Oxford University’s Osney Thermo-Fluid Laboratory, is breaking down barriers in more ways than one. She talked to Scienceblog about her journey so far and how she is using her own experience coming from a minority background to create a brighter future for female engineers to come.

What does your work involve?

Most of my work is in partnership with Rolls-Royce plc, and focuses on the aerodynamics of jet engines, specifically controlling the temperature inside the engine. Jet engines are designed to operate at extremely high temperatures and pressures to be efficient. This means that some parts of the engine are exposed to temperatures higher than the melting points of those parts. This requires some creative cooling methods e.g. internally cooling the turbine blades using a complicated network of passages. My research focuses on finding the novel cooling methods, preventing overheating but at the same time not making it too cool that you decrease its thrust or efficiency.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer Credit: Dr Priyanka Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer Credit: Dr Priyanka DhopadeWhat is your take on diversity in general at Oxford?

I think Oxford has come a long way, but there is still more to be done. It’s a diverse and inclusive environment for research and collaboration and I work with people from various ethnicities on a daily basis. However, given the historical context, I do recognise that there is still this perception that Oxford isn't open to everyone. It can be difficult to change these perceptions and it takes time.

The Diversifying Oxford Portraits initiative is a great example of a tangible change that can help. Outreach programs targeting BME groups and communities that are outside the "Oxbridge" network can also help. The University can only benefit from diversity in all forms - ethnicity, class, gender, disability and sexual orientation. Given the current political climate, I think it's important for educational institutions, especially those as prestigious as Oxford, to set an example of an open, diverse and inclusive community.

The University can only benefit from diversity in all forms - ethnicity, class, gender, disability and sexual orientation. Given the current political climate, I think it's important for educational institutions, especially those as prestigious as Oxford, to set an example of an open, diverse and inclusive community.

What has it been like being a woman studying, working and now teaching engineering?

I have studied and worked in engineering in Canada, Australia and the UK, and the experience has been fairly similar, I have always been in a minority in my industry. After a while that gets hard to ignore. I don’t think it is so much a reflection on the universities themselves, but more to do with the level of my position within them. As my career has progressed, it has become more and more noticeable that I am in a minority in my field.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade coordinates the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, which organises talks, social events and other networking activities for women in the field.

Credit: Dr Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade coordinates the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, which organises talks, social events and other networking activities for women in the field.

Credit: Dr DhopadeHow has it become more noticeable?

As an undergraduate in Canada, I never felt or experienced discrimination. If anything, it was a very positive time for me. I worked hard to really understand the material, and helped other students along the way. When studying for my PHD I was one of the only females in the research group and now as a senior researcher I am the only female - in a group of eighty personnel. Numbers like that are hard to ignore, and you become more aware and frustrated by these issues.

I coordinate the Women in Engineering Oxford group and think I am more of a feminist and an advocate for women in STEM now, than I ever was before, because of my own journey. After a while you just start to think ‘this is not right, I should not be the only woman here.’

Do the women in the group have similar experiences?

There is real camaraderie between the women in my field, which is something I never expected. We are all tied by a common bond, and so understand the issues and support each other. I have made so many female friends across STEM and other PHD areas because of what I do, probably more than I have ever had. It's been great to watch the Women in Engineering at Oxford group, initially created to support the Athena SWAN initiative, grow over the last few years, as more women have joined the research team. Though we still have some work to do to help them progress to high level positions.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer, who works in collaboration with manufacturers like Rolls-Royce plc. Her research focuses on finding cooling methods for jet engines that strike a balance between preventing overheating and not making it so cool, that it impacts thrust and efficiency. Credit: Dr Priyanka Dhopade

Dr Priyanka Dhopade is an aerodynamics engineer, who works in collaboration with manufacturers like Rolls-Royce plc. Her research focuses on finding cooling methods for jet engines that strike a balance between preventing overheating and not making it so cool, that it impacts thrust and efficiency. Credit: Dr Priyanka DhopadeHow do you think these issues and the general imbalance of women working in engineering can be addressed?

It has to be tackled collaboratively by employers and on a policy level. Maternity leave policies are set by the government but have a major impact on how employers view family responsibilities. I know women who have been asked in interviews, directly, if they plan to have children, and if they answer yes, they are seen as not being serious about their careers. I feel that the government sets the tone, and needs to make parental leave a shared responsibility, (as it is in Scandinavia for example). If both men and women had the option of appropriate parental leave it would be seen more as a natural progression of life for those that choose to do so, not just something that women want. I think things are moving in the right direction, but it is a long process.

Unconscious bias is a big issue that does not get much attention. It is difficult to get people to challenge and face up to their own implicit biases, everyone has them, but are rarely willing to admit to them. There is already some great training underway, like the Royal Academy of Engineering and Royal Society of Science, who are rolling out unconscious bias recruitment programmes. But more is needed to encourage panellists to be open minded, particularly at higher levels of academia.

Unconscious bias is a big issue that does not get much attention. It is difficult to get people to challenge and face up to their own implicit biases, everyone has them, but are rarely willing to admit to them.

Speaking to senior academics at Oxford, I know that the University wants to hire more women, but they just aren’t getting the applications. I’m not entirely sure why that is, but I think confidence has a lot to do with it. Having been in their shoes, without my PHD supervisor recommending me I probably wouldn’t have applied myself. There are not many women in top tier engineering research positions and for that to change there has to be some degree of head hunting for female scientists as well.

How would you describe your experience of Oxford?

I’ve been at Oxford for four, very positive years. We work closely with partner organisations, which means I get to have direct impact on Rolls-Royce plc next generation technology, which is so rewarding.

Dr Dhopade has a passion for astronomy, and in her spare time takes in some spectacular views of the moon, with her telescope from her balcony.

Dr Dhopade has a passion for astronomy, and in her spare time takes in some spectacular views of the moon, with her telescope from her balcony.

What is the biggest challenge in your job?

The biggest challenge is also the biggest blessing; working directly with sponsors. Large external organisations work to their own deadlines, so we have to adapt our working styles and be more flexible.

Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

In academia, continuing my research career at Oxford hopefully. My work has the potential to significantly reduce the environmental impact of civil aviation, which, as air passenger travel continues to rise, is critical. More efficient engines consume less fuel and emit less greenhouse gases. I also want to get more involved in conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.

Did you always want to be an engineer?

Growing up in a South Asian family, the cultural connotations of a career in science were very positive and encouraged, which I think isn’t always the case in the West. STEM fields were seen as stable, financially rewarding professions for boys and girls. My Dad is an engineer too, so I am lucky to have supportive parents who understand the field.

One of my earliest role models was Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman in space, and I had a signed poster of her on my wall growing up. Every time I looked at it, I’d get inspired and think; ‘if she can do it, so can I!’ Female role models play such an important role in a young girl’s life.

Engineering is mentally taxing, how do you like to unwind?

I love travelling and also have a telescope that I am always looking for an opportunity to use (even though Britain's climate is largely uncooperative in this aspect!) and so far, I've seen some spectacular views of the moon and sun from my balcony.

What is your favourite thing about your job?

Working with so many smart people is so inspiring. I feel like I am getting smarter everyday just from being around them.

Dr Dhopade is a an advocate for STEM, and involved in community outreach, conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.

Dr Dhopade is a an advocate for STEM, and involved in community outreach, conveying the importance of engineering research to the general public.A 1,700-year-old Roman sarcophagus was recently 'discovered' at Blenheim Palace. It had been 'hiding in plain sight' - it had been used as a flowerpot in Blenheim's grounds for the last 200 years. It was noticed by an antiques expert who was visiting the palace on unrelated business.

In a guest blog post, Dr Christopher Dickenson, Marie Curie Fellow in the Faculty of Classics and Hardie Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities at Lincoln College, discusses the Blenheim sarcophagus and asks the question: why wasn't I the one to report it?

'Last month a story that made a splash in the national and international press and that was all over my Twitter feed was the ‘discovery’ of an ancient Roman sarcophagus at Blenheim palace. The story was reported by the Daily Mail, the BBC, the Oxford Mail, ITV News, the Times and the New York Times among others.

The newspapers reported that an antiques expert has identified the piece, finely carved with Dionysiac reliefs being used as a flowerpot in the palace grounds. The managers of the estate were apparently unaware of what the object really was and have since had it restored and moved to inside the palace.

The thing is, I remembered seeing the sarcophagus myself on my first visit to Blenheim last April. Above is the photo I took of it – you can see the date if you want proof I really spotted it before it made the news.

My first reaction was to think that I should have been the one to ‘discover’ the sarcophagus and have had my fifteen minutes of fame (the antiques expert who did discover it remains anonymous). I soon realised, however, how extremely unlikely it is that I really could have been the first one to have realised that this plant box was really a 1700 year old Roman grave monument.

Blenheim is within a short bus ride of Oxford, home to the largest Classics Faculty in the world. Over the years countless academics and students must have visited the palace and known immediately what they were looking at. Among the hundreds of thousands of tourists who go to Blenheim each year there must also have been quite a few who knew what it was.

When I mentioned to my wife that I was going to write this blog piece and told her about the Blenheim sarcophagus she said nonchalantly ‘Oh yes, I remember seeing that’. She’s not an archaeologist but she’s been with me to quite a few museums and the truth is that you really don’t need to be an expert to recognise a Roman sarcophagus once you’ve seen a few.

I’ve now done some very superficial internet research to see if anybody else had mentioned the object anywhere prior to the discovery and sure enough they had. Zahra Newby, an expert in Roman Art based at Warwick University discusses it in an article in a book on sarcophagi published in 2011. It is also mentioned in the 1882 publication Ancient Marbles in Great Britain by Adolf Michaelis (sadly the page in question isn’t viewable online so I’ll have to wait till I can get to the library to see what it says).

By searching through Twitter I found that Peter Stewart, head of CARC (the Classical Art Research Centre at the Classics Faculty in Oxford) pointed out there that the sarcophagus is included in this publication when news of the ‘discovery’ broke two weeks ago. I’m sure he must have visited Blenheim and seen the sarcophagus himself.

I also found a drawing of the sarcophagus in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago (viewable on their website) by the early 16th century artist Girolamo da Carpi. The drawing is particularly interesting because it preserves details that have now been lost to damage or to wear. The website calls the picture the ‘Blenheim Sarcophagus’. That can’t of course be what it was known as when the drawing was made because the sarcophagus must still have been in Italy at the time and because Blenheim Palace wouldn’t even be built for another century and a half (between 1705 and 1722 and named after the Battle of Blenheim of 1704).

It seems unlikely, however, (and I should follow this up) that the name has only been given to the drawing in the last few weeks so this too seems to be further evidence that the sarcophagus was already rather well known. Finally, in 2010 somebody anonymously posted a photo of the flowerpot on TripAdvisor with the comment that it ‘looks like a Roman lenos sarcophagus’.

So, it is clear enough that over the years plenty of people – probably far more than my brief survey uncovered – have recognised the sarcophagus for what it really was. So why is it only now that it made the news?

The truth must surely be that everybody who saw it and recognised it simply assumed that the people at Blenheim were fully aware what it was. That was certainly my assumption.

I found it a shame that it was outside and exposed to the elements and would have preferred the board in front of it to have given some information about it instead of saying ‘Keep off the grass’ but I thought that the sarcophagus had probably been placed there on a whim of one of the past Dukes of Marlborough and had been left there because it was now part of the history of the place and everybody had grown used to it.

Not for a moment did I think about approaching someone who worked at the palace and saying ‘Hey, do you realise that ornamental plant box is really a Roman tomb monument?”

I also suspect that the monetary value of the sarcophagus is a big part of the story. I was drawn to the object by its historic interest as a relic of both the ancient world and the great period of the gentleman collectors in the 18th century when I would imagine it was brought to Britain. I had no idea that it would be valued, as it now has been, at £300,000.

It took a very particular kind of expert for the alarm bells to start ringing at the thought of this rare, and extremely expensive object, being slowly but steadily worn away by the British rain – somebody who knows both about the market value of ancient art and knows that people who run historic properties sometimes don’t understand the nature of the objects they house.

In other words it wasn’t so much a question of ‘discovering’ the sarcophagus as having the insight not to take for granted what so many others evidently have taken for granted over the years.

I suppose that the lesson to be drawn here is: never be afraid to point out the obvious. The next time I visit a stately home and see the marble head of an emperor being used as a doorstop or an Athenian kylix put down as a dog bowl I’ll make sure I speak up.'

The original version of this article can be found on Dr Dickenson's blog.

In a guest blog, Professor Stephen Baker from the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, explains the importance of monitoring the emergence of infectious diseases in Asia.

Zoonotic diseases that pass from animal to human are an international public health problem regardless of location – being infected with Campylobacter from eating undercooked chicken in the UK is not uncommon, for example – but in lower-income countries the opportunities for such pathogens to enter the food chain are amplified.

Where I currently work in Vietnam, and across the region, humans have a very different way of interacting with animals being bred for food than would be familiar to those in the UK. If one were to travel to the Mekong Delta region (in the south of Vietnam) it would not be uncommon to see people who keep a large variety of farm animals in, or in close proximity to, their houses. It comes as little surprise that in a country where raw pig blood and pig uterus are commonly consumed, the number one cause of bacterial meningitis is Streptococcus suis, a colonising bacterium of pigs.

The major problem of researching emerging infections is predicting how they arise and how we respond to them once they do.

Given the complexity of zoonotic disease emergence and transmission, it is very rare that an outbreak can be traced back to the first identified human or animal case – known as the ‘index case’ and this remains a substantial challenge. A lack of effective health and surveillance infrastructures in many lower income countries compounds this issue, as we are wholly reliant on individuals entering the healthcare system and getting diagnosed, which seldom happens.

The ideal scenario is that we can identify new pathogens with zoonotic potential in animals prior to them spilling over into humans. However, if we cannot achieve this we need to be aware of their existence and be able to respond by treating people effectively once they are infected. This means rapidly identifying patients with a particular infection, assessing the severity of their condition and diagnosing the agent. Therefore, having sentinel hospitals with well-trained clinical staff, good diagnostics and microbiology facilities is the best opportunity we are going to have to detect diseases.

The most recent example of this is a case of Trypanosoma evansi infection – a protozoan disease of animals and, rarely, humans – that we identified in a woman attending our hospital with an atypical disease presentation. Ultimately, we were able to trace this infection back to her cutting herself when butchering a buffalo in her family house during New Year celebrations – this was the first reported human case of T. evansi in Southeast Asia. Our ability to interact with animal health authorities permitted access to sampling bovines in the proximity of the patient’s house. We found a very high prevalence of the parasite in the blood of cattle and buffalo close to where the woman lived, highlighting a new zoonotic infection in the region and likely a sustained risk.

Diagnostic information has also been vital in data we published detailing an outbreak of fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella sonnei. The reason we found this organism was that one of my clinical colleagues was culturing organisms from children with severe diarrhoeal disease, and realised that these samples had come from children who had been admitted to hospital with a more persistent form of the infection, and several appeared to relapse with the same syndrome. When we investigated the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the isolated Shigella, we observed that the bacteria were highly resistant to fluoroquinolones – the antimicrobials that are used routinely to treat this infection in Vietnam (and indeed globally). We then conducted more clinical and laboratory investigations and found more cases in Vietnam and further afield. Through genome sequencing and a group of international collaborators, we could accurately piece together the emergence of this novel strain into Vietnam, other parts of Asia, Europe and Australia.

These finding were largely serendipitous, but if you are not looking then you cannot find. Unfortunately, this approach is not a long-term strategy for monitoring and preventing the emergence of such pathogens. Sadly, the infrastructure improvements and long-term health studies that are needed to achieve a more sustainable model in lower income countries are an expensive undertaking, but without them healthcare improvements and changes to infectious disease policy will be difficult to achieve.

Vietnam has changed beyond recognition since my arrival in 2007. Huge economic investment and political stability has had positive effects on healthcare in the country, and across the region. However, many challenges remain; a growing population, increasing demands for animal protein and the looming cloud of antimicrobial resistance in everyday pathogens suggest that Southeast Asia will continue to be a key region in driving global health security.

The full article, ‘Emerging infectious diseases in Asia,’ appeared in the latest edition of the Microbiology Society’s quarterly magazine, Microbiology Today.

Yesterday, Britain triggered Article 50 to begin the formal process of leaving the European Union. To mark the occasion, our guest author today is Katrin Kohl, Professor of German Literature at Oxford, who leads a major research project into languages called Creative Multilingualism.

'Creative Multilingualism – Oxford’s biggest ever Humanities research programme – got off the ground on 1st July 2016, a week after the Referendum vote to leave the European Union. The nature of the research, and the funder’s requirement that it should have an impact on UK society, have made it impossible to ignore the interplay between research and politics.

The programme is being funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of their ambitious Open World Research Initiative. At a time when the political emphasis has been on strengthening borders and building walls, the only option for our research team has been to embrace the connection between research and politics as part of multilingualism’s rich tapestry.

Languages are inherently and inexorably connected with the cultures of the people who learn them, care about them, and use them. And culture is never apolitical – as we have seen in recent months, cultural identity matters, and a passion for status can drive political decisions.

The British people (or just over half of them) decided that even though it made no economic sense to many experts, would tie up British energies for years to come in cutting and creating red tape, and would pose immeasurable difficulties for organisations ranging from the civil service through orchestras to the NHS, the time had come to put the Great back into Britain.

It has become clear that the fault lines within the British nation are complex and by no means reducible to class difference or education. An intriguingly large number of politicians on both sides of the Brexit fence were educated at Oxford.

And the Government’s commitment to hardening borders seems to have as much to do with Britain’s island identity and distrust of globalisation as with evidence concerning national interest. When Michael Gove said that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was responding to the fact that appealing to emotions can be more persuasive in politics than rational evidence.

Over the many years of EU-membership, the British never overcame the tendency to refer to ‘Europe’ as a continent beyond Britain – Europe still begins at Calais. Successive governments rarely made a positive case for EU membership that might have fostered a sense of common identity or purpose.

Even the Remain camp side-lined the role of emotional factors in the nation’s decision-making, and failed to appreciate the effectiveness of a Leave campaign based on the community-building vision of enhanced national status outside a Union that was bigger than Britain, or England.

There are lessons to be learned here for the current crisis in Modern Languages. The more languages have been reduced in schools and society to being fostered only as a useful practical skill, the less they have appealed to learners who choose their subject because they enjoy them.

Like the economic arguments underpinning the Remain campaign, the argument that Britain needs language skills to improve its exports has fallen on deaf ears because it fails to touch emotions and appeal to personal identities.

The argument that language skills might one day be useful for their careers has likewise proved ill-suited to persuading young learners that the hard graft is worthwhile. If young people are to be sustained through the long process of learning a language, they need to be rewarded by a richer, more engaging experience of the many ways in which languages contribute to our lives as human beings.

When languages engage you at a deep level, they start interacting with all those human capabilities that make each human different, and each cultural group distinctive. They also interact with what makes each of us creative in an individual way. Creative Multilingualism is designed to tap into these interactions and give them space to flourish.

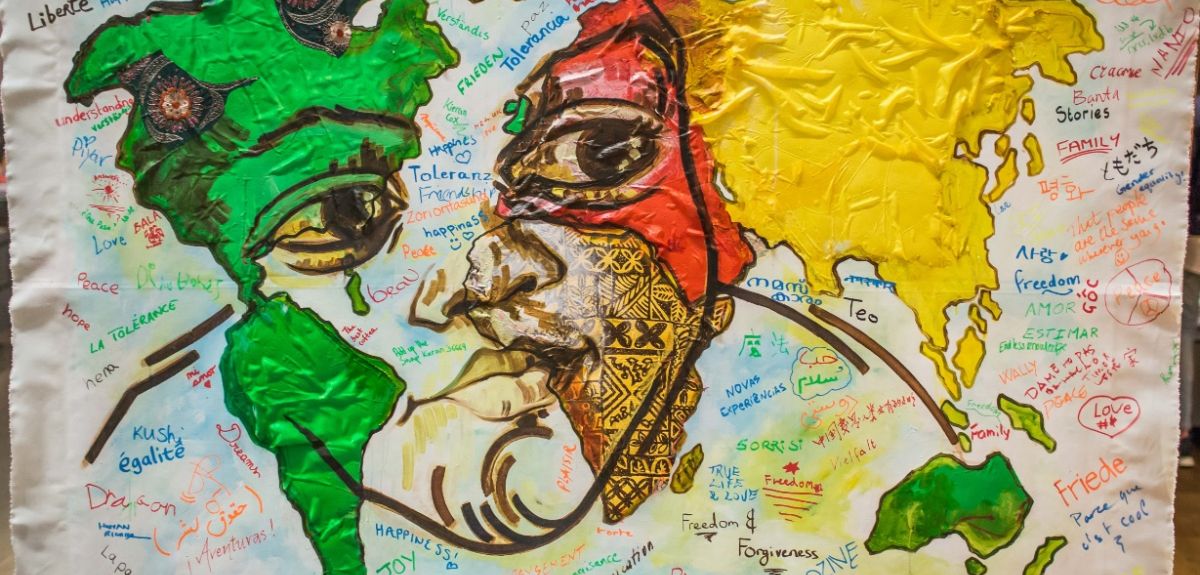

Nine months into the project, we can look back on a highlight that inspired hearts and minds as they transcended cultural divisions while celebrating cultural diversity – LinguaMania, which brought some 2500 people together from many cultural provenances. Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum became a setting that was alive with cultural expression – from the Afro-Brazilian samba rhythms, language tasters and cuneiform tablets to a crowd-sourced translation of Harry Potter into 52 languages contributed by the visitors in the course of the evening.

Languages build channels through time, and thankfully they don’t stop at borders any more than cultures do. Britain is no more separate from Europe linguistically and culturally than it is separate from the continent and bigger world of which it forms a part.

LinguaMania visitors looking at an Aramaic fragment of pottery experienced a glimpse of the concerns people had in Egypt around 475 B.C: “To Hoshayah: greetings! Take care of the children until Ahutab gets there. Don’t trust anyone else with them!”

And on the reverse, following a recipe for bread: “Tell me how the baby is doing!” As we renegotiate our relationships within Europe and a rapidly changing world, it’s worth thinking about the values, cultures and languages we share with ancient and contemporary peoples.

Britain right now is a good place to start exploring the multicultural and multilingual riches that are, and will remain, part of our country.'

The Red Mansion Art Prize Exhibition 2017 is on display at the Kendrew Barn in St John's College this week.

The exhibition is being presented by the Ruskin School of Art and the Red Mansion Art Foundation, and displays work by the winners of the Red Mansion Prize 2016.

The Prize is awarded to one student from each of the UK's seven leading art schools every year. Each of these students visited China for a fully-funded residency in the summer of 2016. They were given studio space and the opportunity to work alongside local artists.

The results of this work have been brought together in this week's exhibition.

This year's winner from the Ruskin School of Art is Olivia Rowland.

'The cultural experience really made me reexamine not only my own practice and processes, but the way I examine and take in the world at large - both as an artist, and as an observer,' she says.

The exhibition has been curated by Ian Kiaer, an artist and tutor at the Ruskin School of Art.

He says: 'The Red Mansion Prize provides an opportunity for selected students across seven of the UK’s major Fine Art programmes to work and exhibit together, allowing them exposure to, and dialogue with, some of their most promising peers, as well as artists in China.

'It is also significant that this is the first time the event is happening in Oxford, bringing early-career artists to the heart of the collegiate University.'

The exhibition closes this Friday (31 March) at St John's College.

DYSPK by Natalie Skobeeva

DYSPK by Natalie Skobeeva- ‹ previous

- 100 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?