Features

Meeting Alison Woollard over a coffee is a delight. It's clear she is a story teller. She is engaging, enthusiastic, chatty, fun, easy to relate to, has lovely turns of phrase and illustrates everything with great tales and examples. I thoroughly enjoy the conversation and my time with her.

But those are all incidental skills of a presenter. She also has a great story to tell: Where we all come from.

And that's surely why she's been chosen as this year's Royal Institution Christmas lecturer.

The Christmas Lectures are an institution in themselves. Broadcast annually since 1966 from the Royal Institution's tight, high-sided lecture theatre, they are a fixture in the TV schedule as soon as the turkey and present opening have finished and a cornerstone of science education and outreach in this country.

Started by Michael Faraday in the first part of the 19th century, the lectures have always been loaded with showpiece demo after demo to illuminate the latest in scientific understanding in an accessible way for children (and their parents).

Dr Alison Woollard is Dean, Fellow and Tutor in Biochemistry at Hertford College, and a University Lecturer in the Department of Biochemistry, where her research looks at the nematode worm as a model system for understanding embryonic growth and development.

Her Christmas lectures on Life Fantastic will uncover the transformation through which a single cell becomes a complex organism. She will look at where we come from, what makes us, how we grow and how we age, but also how we might want to harness this knowledge and the questions it raises.

The lectures will bring in all sorts of subjects: covering some of the working of cells, developmental biology, how morphology changes over time, and evolution and the role of chance in shaping us as organisms.

So at Christmas time, when many people around the world will be celebrating a miracle birth, Alison will be explaining the amazing process by which a newly fertilised egg cell divides and grows. Or as she says: 'How cells in the growing embryo know what to do in the right place at the right time. How cells, all with the same DNA instructions, know to become liver cells, eye cells or toenail cells.

'It's all about interpreting those instructions,' she explains.

While it quickly becomes clear to me that she will make a tremendous presenter, when Alison first received an email inviting her to put herself forward for the Christmas lectures, her first reaction was to delete the email.

A few days later, she tells me, she retrieved the email from trash so she could at least leave it sitting there in her inbox. She then did nothing for a week. After a subsequent email chasing her, she did then draft a short proposal for the lectures and sent it off. She was surprised to get an audition. 'I'm still a novice,' she protests, though she admits that won't be the case come the New Year.

The Christmas lectures can draw anywhere between 1 and 4 million viewers, and is likely to be BBC Four's biggest show over the Christmas period.

'It's an enormous privilege,' says Alison. 'Other lecturers have had letters years later from scientists who say they were initially inspired by watching them.

'If my lectures are able to inspire any of the children in the lecture theatre or those at home, then job done!'

She suspects that the TV audience has a range of ages and interests, but doesn't believe that is a problem. 'The lectures need to be accessible to children and adults alike, and I don't see much difference. I think you can begin with basic ideas and go right up to the cutting edge, guiding people through and taking them with you.

'In my case, I have my 10 year old daughter at home to try stuff out on, and my mum at the other end of the spectrum.'

She is keen to use her set of lectures to go beyond explaining the pure science, and also explore some of the issues and ethical dilemmas it can raise.

'Part of my area of science includes new cell-based medicine and genome sequencing,' Alison says. 'These technical advances are important and raise some issues. There is a tremendous opportunity to improve human health, and a consensus will need to be reached on the issues.

'For example, where do we draw the line on screening for genetic abnormalities in embryos? If when born, we are presented with the complete sequence of our genome, we will need to understand risk to interpret information on what our genes may say about our future health.

'These need to be discussed, not just by scientists but by the public more widely. There is an absolute responsibility for scientists to take their science into society.'

Alison is also very clear on the importance of 'science where we don't know where it is going to lead; science that is blue skies, curiosity-driven, non-impact led'. She adds: 'Many medical advances have been purely serendipitous, arising unexpectedly from studying a biological problem.'

She points to the example of the important biological process known as 'apoptosis', or 'programmed cell death'. This is a normally well controlled and regulated process that is important in the development of an embryo, and is also a way in which cells in tissues that are stressed or damaged are shut down and broken apart.

Alison explains: 'The process was first identified in the nematode worm. The process's importance became clear when mutants lacking an active cell death pathway didn't develop properly and the embryos would die.

'Apoptosis is also important in cancer formation in humans. The inability of cells to die when they should, coupled with the uncontrolled proliferation of cells can drive the growth of a tumour.

'The molecules involved in apoptosis are very highly conserved. Those in the worm are similar to those in a human tumour. Studying simple, model organisms such as the worm can have an enormous impact on cancer medicine and biomedicine in general.'

Alison notes that she is only the fifth woman to do the Christmas lectures since they began in 1825. 'Which is kind of shocking,' she says.

She believes that there is much still to be done to solve the poor representation of women in many areas of science. It's not that male scientists are necessarily discriminatory or sexist, she says, the biggest problem is the career path. The need to keep producing results and journal papers, to work all hours in the lab, to keep going to conferences, all the things you need to run a successful research group – it is hard to marry that with having a family.

Alison took six months' maternity leave for each of her children, but much of that time she was still running her lab. 'Who else would know my research to direct it?'

She adds: 'Looking back, it was detrimental to my own experience to try and do all these things at the same time.'

Wanting a sneak preview of the lectures, I ask about the demos the Christmas lectures are known for.

'The demos are not worked up yet,' Alison says, to my disappointment. 'Unlike chemistry, where you can put two chemicals together and get a big explosion but there is perhaps more difficulty building a narrative, biology has extraordinarily profound ideas but you need to find the bangs.

'A lot of biological material needs microscopy to see what's going on,' Alison points out. 'We'll need good microscopy and good projection to grab the attention. We're thinking about great, high tech ways of doing this,' she reveals. 'One thing I can promise - we'll see life unfurl before our very eyes.

'We can also balance this with audience participation. Biology lends itself quite well to games, and we're thinking about that too,' she says.

As we continue to enjoy the summer, there are some things about Christmas I can't think about yet: Christmas shopping, the heavy eating and drinking. But watching Alison's Christmas lectures is one thing I'm already looking forward to.

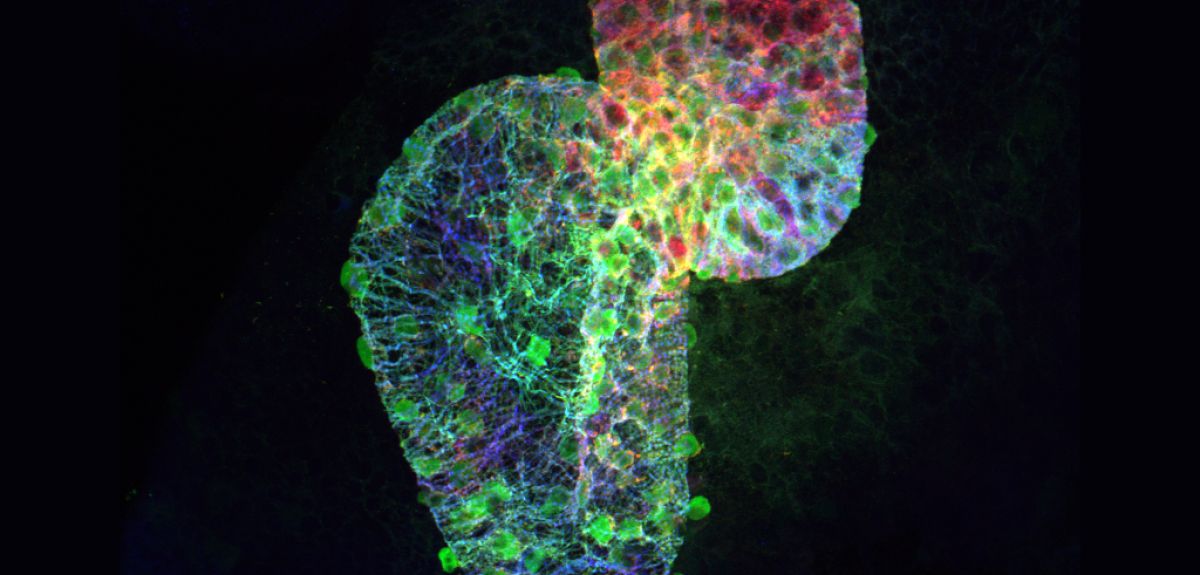

This picture shows the heart of a two-day-old zebrafish.

Its striking beauty has seen it win the Mending Broken Hearts prize in the British Heart Foundation's competition for outstanding images and videos from the research it funds.

The image was produced by Dr Jana Koth as part of her research at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine at Oxford University.

Under the microscope, it is possible to see individual cells and the internal organization of the early heart as it grows and develops. The green cells are heart muscle cells, and the red and blue staining shows components that make up the muscle. The heart consists of two sections – the large, thin atrium (where blood flows in) and the smaller, thicker ventricle (where blood leaves the heart).

Remarkably, the hearts of zebrafish can repair themselves after damage, something which human hearts cannot do. The hope is that understanding this ability might in the future allow ways of prompting heart repair in people who have had heart attacks and develop heart failure, an area of research known as 'regenerative medicine'.

On winning the prize, Jana said: 'I'm stunned and delighted to receive this year's Mending Broken Hearts award. In the course of our regenerative medicine research we produce images like this all the time. They help us to uncover the secrets of the zebrafish. It's great to be able to take a step back and admire the beauty, as well as the biology, of this natural wonder.'

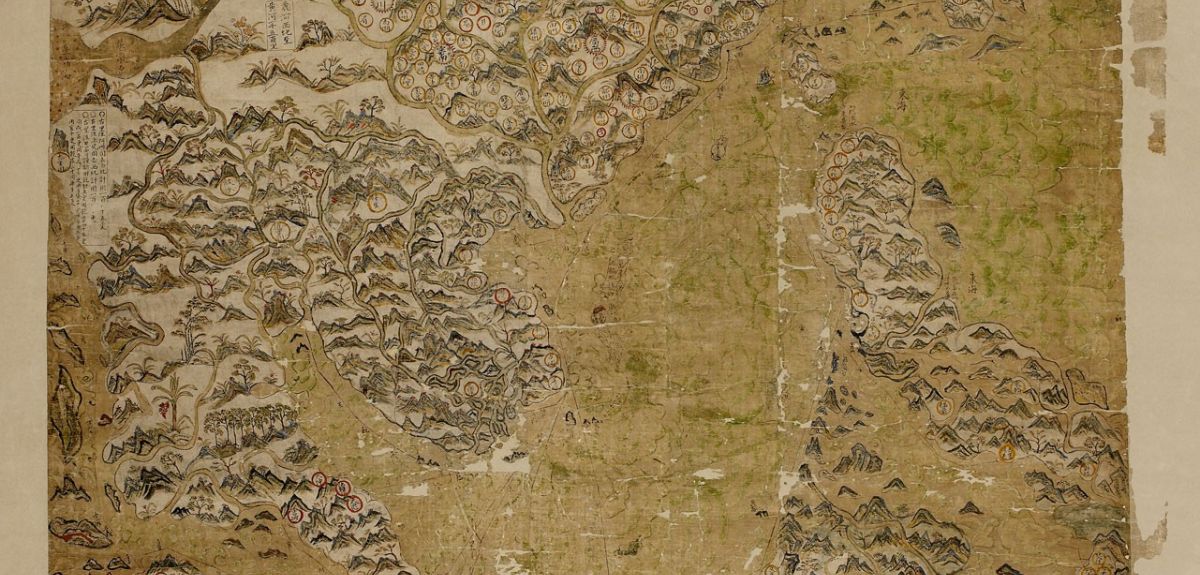

It was once described as 'a very odd map of China'. Today, the 17th-century Selden Map – which London lawyer John Selden bequeathed to Oxford in 1659 – is one of the treasures of the Bodleian Library.

David Helliwell, curator of Chinese collections at the Bodleian, explained: 'We don't know exactly when the map was made, nor do we know exactly where it was picked up in the Far East, but we imagine that it was probably made in 1620. It was acquired by a merchant of the East India Company and brought to London, where it passed into the hands of Selden. But we don't know exactly how, and we don't know exactly when.'

The newly-launched Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), which seeks to promote interdisciplinary collaboration, invited a number of scholars from different disciplines to cast their eye over the map. The resulting short film throws up a wide range of intriguing, interrelated perspectives.

Dr Kate Bennett, an English lecturer with a research interest in antiquarianism, was one of the academics invited to have their say. She said: 'What we can certainly say is that Selden knew a very interesting potential source of study and scholarship when he saw one. His works were things that he had collected to help his own scholarship, which was formidable.'

Rana Mitter, professor of the history and politics of modern China, hailed the value of the Selden Map in providing historical context for our understanding of the region today. He said: 'One of the things that has emerged from the research I have done is that things that we consider to be natural circumstances – the idea perhaps that China and Japan might be in conflict or hostile with each other – are actually often historically determined and often rather short-lasting. In other words, looking at the map gives you that longer-term view – a reminder that the kind of understanding we have of this immensely important region has to be informed by an understanding that trade routes, relationships, commerce and people engaging with each other has a long history. The map is a marvellous example of that.'

Ros Ballaster, professor of 18th-century studies, added: 'There was a lot of enthusiasm in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to find ancient cultures other than Greek and Roman classical culture, and that's a strong line in talking about China through the 17th and 18th centuries – as an alternative classical culture. I think that's what Selden is, in a way, trying to collect.'

As well as being an interesting object from a historical perspective, the Selden Map is also an important piece from an artistic point of view. Ros Holmes, a researcher in contemporary Chinese art, said: 'One of the most interesting things for me about the Selden Map is the sheer richness of the detailing itself. What first appears to be a 17th-century map about Chinese trade routes is actually a more complicated art historical object that attests to cross-cultural flows of knowledge and an exchange of ideas – not just about pictorial representation but about how China visualised itself in relation to the rest of the world.'

Mr Helliwell agreed about the visual impact of the map. 'It was probably a map that almost had a half aesthetic function and it was probably displayed in the house of a rich merchant,' he said. But for Mr Helliwell the most striking aspect of the map lies in its scope, and what it tells us about commerce in this period. The map extends to the whole of the Far East, with China only in the top half and the South China Sea at the centre. He said: 'This is a map drawn by ordinary people. It’s drawn by tradesmen – tradesmen who simply wanted to illustrate the routes on which they plied their trade.'

Image of the Selden Map courtesy of the Bodleian Library.

Why is the sky blue? It's a simple question but one with a surprisingly complex answer if the sky belongs to a planet outside our solar system.

'If you are on Earth looking up the sky looks blue because other wavelengths of light are scattered by molecules like oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere,' explains Tom Evans of Oxford University's Department of Physics. 'If you look at the Earth from space it appears (mostly) blue both because of this effect and because water in oceans and lakes absorb other wavelengths, only reflecting blue light back into space.'

So viewed through an astronomer's eyes colour is much more than a pretty effect: it's an invaluable source of information.

Now, for the first time, scientists have determined the colour of a planet outside our solar system (an 'exoplanet'). Because they are so distant, and so much smaller than stars, seeing exoplanets directly with current telescopes is normally impossible (most of what we know about them comes from indirect observations, for instance of nearby stars).

An international team, led by researchers from Oxford University and Exeter University, took advantage of a secondary eclipse, when a planet disappears behind its star. They used the Hubble Space Telescope to study the moment the exoplanet 'HD 189733b' passed behind its parent star so that they saw both the star's light and light reflected off the planet (its 'albedo') and then, once HD 189733b has disappeared, just the star's light on its own.

From the difference in brightness between these two observations they were able to infer HD 189733b's brightness and by examining the wavelength of light reflected off it they were able to determine that it would appear a deep cobalt blue to our eyes.

But HD 189733b, which is 63 light-years away, isn't blue because it is like Earth.

'It's very different from the planets in our solar system,' Tom Evans, first author of a report of the research in Astrophysical Journal Letters, tells me. 'Unlike Jupiter or Saturn this gas giant orbits very close to its star, so it's bombarded with massive amounts of radiation and its atmosphere can reach a temperature of over 1000 degrees Celsius. The planet is also tidally locked so that one side is permanently facing its star whilst the other side is in eternal shadow.'

Suzanne Aigrain of Oxford University's Department of Physics, also an author of the report, comments: 'Despite these differences the laws of physics are the same, and as every planet with an atmosphere in our solar system has clouds we can infer that HD 189733b has clouds. We suspect that these clouds are made of silicate particles, but we don't know how and where they are formed, and the fact that they could be moving at very high speed (with winds of up to 7000 kilometres per hour) makes observations very difficult.'

The researchers believe that a large part of HD 189733b's blue appearance is down to sodium atoms in its atmosphere, as sodium atoms absorb more light at red wavelengths. 'If it wasn't for sodium absorbing the redder wavelengths, the planet would probably be more of a white colour,' Tom explains.

'This planet has been studied well in the past, both by ourselves and other teams,' says Frédéric Pont of the University of Exeter, leader of the Hubble observing programme and an author of this new paper. 'But measuring its colour is a real first — we can actually imagine what this planet would look like if we were able to look at it directly.'

HD 189733b's system is one of the best studied of all exoplanet systems because its star is bright and close to its planets, making interactions easier to spot. 'It's one of the most favourable systems, there aren't many where we can do the same thing,' comments Suzanne. But its parent star does pose some problems; it's an orange dwarf (or 'K-dwarf'), around four-fifths the size of our Sun, that's very magnetically active so it regularly shoots out flares and star spots that can interfere with observations.

'One of the next questions to answer is just how much of the parent star's light HD189733b is absorbing, because the wavelengths we've measured only account for about 20 per cent of the starlight that falls upon the planet,' Tom adds.

Determining exactly how much energy is being fed into its climate system overall has important implications for the circulation and weather on the planet. To do this, the astronomers will need to extend the measurement at longer wavelengths. This will allow them to confirm that none of the red or near-infrared light can escape from the atmosphere, as they currently suspect.

Other members of the Oxford team, along with collaborators at Bern University, will now begin to feed all the data from the recent observations into a model of the planet's atmosphere. 'A lot of what we do draws on models produced using data from gas giants in our own solar system. These enable us to make some basic predictions, although we know that if we push these models to extremes some of these assumptions break down,' Suzanne tells me.

'We would also like to do similar measurements for other planets, to understand how pervasive clouds are in these 'hot Jupiter' planets,' she adds. 'Currently Hubble is the only telescope we can do this with, and it's not clear how many planets we can do it for (HD189733b is one of the most favourable targets). But in the future we may develop clever techniques that enable us to do some of this from the ground, though it's harder because the Earth's atmosphere gets in the way.'

The hope is that with new, more powerful instruments like the James Webb telescope and especially the proposed European space mission EChO we might be able to get an even better glimpse of the atmospheres (and colours) of this and other exoplanets.

It's not an easy task to stand on top of a box on London's busy Southbank and try to entertain everyone and anyone in the passing crowds of tourists, school pupils, city workers and arts lovers. Even if you are a stand-up comedian, performance artist, or street entertainer, it would probably still be many people's idea of a tough gig.

Standing on that box and engaging people in the latest scientific research surely makes it even harder. Yet it doesn't appear to phase Dr Ravinder Kanda. Ravinder is a research associate in paleovirology and genomics in the Department of Zoology at Oxford University, and she is one of 12 scientists taking part in Soapbox Science on Friday July 5.

The event, supported by L'Oreal UNESCO For Women In Science Scheme, is now in its third year and gets some of the UK's leading female scientists to talk passionately about their subjects to the general public. Its aim is to help eliminate gender inequality in science by raising the profile, and challenging the public's view, of women and science.

OxSciBlog caught up with Ravinder to learn more about her research and what she'd be talking about to all comers from the top of her soapbox on the South Bank.

You also can read an interview with Ravinder about her research and her career in a blogpost on the Soapbox Science website.

OxSciBlog: What are endogenous retroviruses and why are they so interesting?

Ravinder Kanda: Only 2% of our DNA is used to build our bodies. The rest of it – noncoding DNA – is a mixture of old genes that have lost their function, repetitive strings of DNA whose function is not understood, and other elements. Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are a kind of noncoding DNA that make up 8% of our DNA. ERVs are all descended from viruses, very like those that cause disease, like HIV, which managed to insert themselves into our ancestors' DNA in the distant past.

OSB: When and how do we think ERVs got incorporated into our DNA?

RK: The way this particular group of viruses, called retroviruses, infect a cell involves inserting themselves into the DNA of the cell – they become part of our DNA. Once inside the DNA of a cell, new copies of the retrovirus can be produced using the cell's machinery. These new copies can then leave the cell and go on to infect other cells. Occasionally, a retrovirus will infect the germ-line cells – the cells that produce sperm and eggs. In this instance, the virus is now part of the DNA of that sperm or egg cell. When fertilisation occurs, this one cell divides to become two. Both cells now contain a copy of the virus. Two cells go on to make four – all have the viral DNA too. When that fertilised egg develops into an adult, every single cell in that individual's body contains the viral DNA. When this happens this virus is known as an endogenous retrovirus, meaning it is within our DNA. It is inherited by all the offspring of that individual.

There are around 100,000 copies of these ERVs in our genome. By comparing the DNA of other primates and mammals, we can estimate how long ago these ERVs inserted into the DNA of our ancestors. For example, it is estimated that the common ancestor of our closest relative, the chimpanzee, and modern day humans existed approximately 8 million years ago. If a particular ERV is present in the DNA of both humans and chimpanzees, we can say that it must have inserted into the DNA of our ancestor more than 8 million years ago. We can then look at the next closest relative, the gorilla, and see if the ERV is present in their DNA. If it is present in the the gorilla, the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas is thought to have existed around 15 million years ago and so we can say that the ERV inserted into the DNA of our ancestors 15 million years ago. Some of the ERV insertions are ancient, dating back 100 million years.

OSB: How might these 'DNA invaders' be good for us?

RK: In some instances, we have managed to 'borrow' some of the viral genes and use them for our benefit. The most famous example is a gene that is involved in pregnancy, specifically with the formation of the placenta. This gene comes from a virus and is essential for the formation of the placenta. Without it we would not be able to reproduce as we do. In other species, there are instances where having a particular ERV gives you some protection against infection from other related retroviruses. For example, sheep have a particular ERV that can block the receptors of a cell, preventing entry into the cell and therefore infection by other related viruses.

OSB: What can ERVs reveal about the evolution of infections in animals and humans?

RK: Many ERVs in our DNA are ancient, indicating that this invasion has been occurring for millions of years. By comparing those viruses that are present in DNA to viruses that currently infect and cause disease, we can see that some of these viruses are very good at making a leap and infecting different species to those in which they were originally found, something called cross-species transmission. For example, we know that HIV was a virus that originally infected primates. The subgroup of viruses to which HIV belongs – lentiviruses – has recently been discovered in the DNA of other species. These discoveries challenge our understanding of how these viruses might change and evolve.

OSB: What further research is needed to understand more about ERVs?

RK: Lots! We are only just beginning to understand what an influential role viruses may have played in many various aspects of the evolution of a species. One consideration is that some viruses can make the leap to infect other species, such as HIV. A better understanding of cross-species transmission, why or how this occurs, and why some viruses are better at doing this than others, may also help us identify potential 'hotspots' of infection. This could allow us to be better prepared against possible future threats.

For me personally, I am interested in the role that ERVs play with regards to offering immunity against infection from other viruses. The idea of using viruses against themselves is an interesting one. However, we need a better understanding of exactly how this occurs. We still have a long way to go.

- ‹ previous

- 180 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools