Features

'The world urgently needs new medicines for many diseases such as Alzheimer's, depression, diabetes and obesity,' says Professor Chas Bountra. 'Yet the pharmaceutical industry's success rate for generating truly novel medicines remains low, despite investing tens of billions of dollars.'

What's going wrong? Why can't we depend on the vast commercial pharma industry to deliver the new treatments we need? Professor Bountra is in the ideal position to ask. He came from the drug firm GSK to lead the Structural Genomics Consortium at Oxford University, a public-private partnership that bridges academia and industry and produces data that is directly relevant for coming up with new drugs.

'What the pharma industry has done is recruit some of the smartest people on the planet, invested tens of billions in technology and infrastructure, and acquired promising companies,' he says. 'It's not that industry is doing anything wrong. The problem is that it's so difficult. The fundamental bottleneck is our ability to identify new targets for drug discovery.'

Those working in this area talk about 'targets'. If you have a biological molecule, most often a protein, that you find is critical in a disease process in the body, this is a target.

It is a target because you can throw tens and hundreds of thousands of small chemical compounds at it and see which of these would-be drugs stick. You might come away with a handful of compounds that bind your target protein and block the disease process. Now you have somewhere to start, you have some candidate drugs against this disease.

You'll want to optimise the chemical compound, do toxicology checks, and there would be years of clinical trials to determine it was safe and beneficial. But the starting point turns out to be crucial. If you don't know enough about the target and the disease process it affects, you may waste billions of pounds, years of effort and expose patients to something that may have no medical benefit – or worse, find side effects you didn't know about.

Professor Bountra explains: 'There are around 22,000 different proteins in humans, any of which could be a target for a drug. There are hundreds of diseases and hundreds of subsets of diseases. What we can't do right now is say this protein will work in this subset of Alzheimer's patients.

'Pharma is extremely good at taking a candidate drug molecule through to market. None of us – and I include the whole global biomedical community in this – is good at selecting the right target for drug discovery.'

Peter Ratcliffe, Nuffield Professor of Medicine at Oxford University, is of exactly the same mind: 'It's almost self-evident that in starting drug development you need to start in the right place. We need to have the right molecular target.'

He is the director of the new Target Discovery Institute at Oxford University, an institute whose whole purpose is validating targets for drug discovery.

Researchers have just started moving into the TDI's impressive new building on the Old Road Campus. All clean lines, sharp angles and a glass frontage to guide you in, it brings the best biologists and chemists together with the latest genetic and cell biology technologies.

Modern biology research is delivering thousands of potential targets, Professor Ratcliffe says, but it is currently hard or impossible for scientists in pharma to know which are the most promising to pursue for new drugs. He believes that at least a portion of academic research should be more aligned to what industry needs to take things forward.

One of the examples Professor Ratcliffe gives is a set of enzymes called histone demethylases. These are involved in switching genes on and off in cells, and drugs targeting these proteins may be useful in cancer and inflammatory disease. But this work is still at a relatively early stage and there is a lot to be done to determine the range of effects that blocking these enzymes can have, and whether discrete medical benefits can be achieved. That's where the interest of the TDI comes in.

Forging successful partnerships between academia and industry is exactly what Professor Bountra has done at the SGC. This not-for-profit group, which with academic and industry partners worldwide determines the three-dimensional structures of proteins of importance to human health, places the data in the public domain, open and free to all. Knowing the structure of a protein is important in finding candidate drugs that bind this target.

More recently, the SGC began working further along the drug discovery chain in coming up with novel chemical compounds that block target proteins. Again the data and reagents are openly available to allow anyone to investigate them. Some novel drug compounds are already being taken forward by new biotech companies.

'We need to pool the strengths of academia and industry,' Professor Bountra believes, 'to create a more efficient, more flexible way of discovering new drugs. It is only by pooling resources and by working with the best people that we can hope to reduce costs and reduce risks in this very difficult task of discovering new drugs.'

Professor Ratcliffe adds: 'The failure of drug candidates at a late stage in large-scale trials is reasonably held to be the thing killing the pharma industry. We have to secure the rationale for developing a drug in the first place, and we have to make sure we don't find untoward aspects at a late stage.'

Both professors believe that there is wider importance to the British economy, following many drug companies downsizing their research capacity in the UK. By making these projects in Oxford a success, it can bring in drug company investment, it can see new biotechnology companies spun off and help in retaining highly skilled people in this country, they say.

'I honestly think what is happening in Oxford is phenomenal,' says Professor Bountra. 'In the next one to two years, Oxford will be the academic drug discovery centre in the UK. What distinguishes Oxford is a culture that makes all of this work. We are all pulling in the same direction to help industry develop new medicines because society desperately needs new medicines.'

This article was originally published in Blueprint, the University's staff magazine.

The health of the ocean is spiralling downwards far more rapidly than previously thought, according to a new review of marine science.

The latest results from the International Programme on the State of the Ocean (IPSO) suggest that pollution and overfishing are compromising the ocean's ability to absorb excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. IPSO's scientific team warns that the oceans won't be able to shield us from accelerating climate change for much longer and that mass extinctions of some species may be inevitable.

'What the report points to is our lack of understanding of both the role of the ocean in taking up CO2 and the impact of human activity on marine ecosystems,' Alex Rogers of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, Scientific Director of IPSO, told me.

The findings are published in a set of five papers in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, the papers came out of meetings hosted at Somerville College, Oxford.

'Our research at Oxford is trying to fill in these gaps in our knowledge about how carbon is transported in the deep ocean,' Alex explains. 'We need more research in particular into the active processes taking place as animals migrate up and down in the ocean every day.

'Animals such as deep water fish will feed in surface waters at night, then migrate up to 1,600 metres back down into the deep. Animals like jellyfish repackage carbon ingested during feeding and excrete it as faecal pellets. We also see mass die-offs of deep sea animals – how this contributes to the carbon cycle, and how it might be affected by climate change, is very poorly understood.'

Alex highlights how estimates of the biomass from fish from the 'twilight zone' region (200-1000 metres deep) were recently found to be out by a factor of ten because it was not realised that these mesopelagic fish were actively avoiding underwater nets.

'That we can get the numbers out by this amount just demonstrates the poor level of knowledge about our oceans,' Alex comments.

Much more research is needed, he believes, if we are to understand how climate change both affects and is influenced by marine ecosystems.

Read more about Oxford research into the deep ocean in our stories about a 'lost world' of new species discovered deep beneath the Southern Ocean, and the origins of the hairy 'Hoff' crab.

Travelling in flocks may make individual birds feel secure but it raises the question of who decides which route the group should take.

Mathematical models developed by scientists suggest that a simple set of rules can help flocks, swarms, and herds reach a collective decision about where to go. But investigating how this really works, especially with animal groups in flight, is extremely challenging.

A new study led by Oxford University scientists, reported in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, has used the sort of high-resolution GPS technology normally reserved for extreme sports to look at how homing pigeons make decisions on the wing.

I asked lead author Benjamin Pettit of Oxford University's Department of Zoology about the research and what it tells us about the rules of the fly game…

OxSciBlog: What are the advantages of flying in a flock?

Benjamin Pettit: For pigeons, the main advantage of flying in a flock is to lower the risk of being eaten. Therefore pigeons in flocks need to coordinate their behaviour to stay together - something they have in common with many other animals. In addition to safety, there might be navigational advantages to flying as a flock. For example, when a flock of pigeons flies home together, the route they take will potentially combine navigational knowledge of many birds.

OSB: How are pigeons able to 'share information' in flight?

BP: Until now, nobody has directly measured how pigeons respond to each other's movements in flight, but from mathematical simulations we know that flocking can arise from simple rules based on visual cues, namely 'stay with the group,' 'avoid collisions,' and 'head in the same direction as those around you.'

If each bird is also paying attention to navigational cues, like familiar landmarks, then flocking rules will be effective at sharing information within the flock. What we do know from previous data on pigeon flocks is that there isn't always an equal, two-way exchange of information, and instead some pigeons have more of a leadership role within the flock.

OSB: How did you explore group navigation behaviour?

BP: We studied the simplest flocking scenario of two pigeons flying home together. Each pigeon had its own preferred homing route, which meant we could test how each pigeon's preference factored into the pair's route, and also find out how the group decision arises from the pigeons' momentary interactions during the flight.

The pigeons carried lightweight, high-resolution GPS loggers, which were actually designed for extreme sports. It was also the right technology for racing pigeons. Working together with mathematical biologists at Uppsala University in Sweden, we created a simulation based on the interaction rules that we inferred from the GPS data, which was a useful tool for studying pigeons' group decisions.

OSB: What did you find out about the rules governing this behaviour?

BP: Pigeons responded to each other by adjusting their speeds and making small turns, maintaining a close, side-by-side configuration most of the time. A pigeon was sensitive not only to its neighbour's position, as has been observed in fish schools, but also to the direction its neighbour was headed.

The flocking behaviour was stronger toward a neighbour in front than behind, which means that a faster pigeon that consistently gets in front has more influence over the pair's route. This simple leadership mechanism based on speed is something we investigated with a combination of the data and the simulation.

Our findings show how real bird flocks compare to the 'rules of motion' postulated in simulations over the past three decades.

OSB: How might your findings help us understand group navigation in other animals?

BP: First of all, we found that persistent leadership-follower relationships observed in nature are not necessarily something complicated that requires animals to recognise each other and assess each other's ability. The mechanism can be as simple as a difference in speed.

Second, we found some similarities with fish in terms of how flocks/schools are formed, but also some differences that are likely due to the biomechanics of flight versus swimming.

The pairwise configuration of pigeons is similar to that observed in starling flocks. Rather than converging on a 'universal' flocking rule, different animal lineages have their own solutions for collective motion, which affect the shapes of schools, herds, and flocks. The particular interaction rules will also affect how information passes through these groups from one animal to another.

A report of the research, entitled 'Interaction rules underlying group decisions in homing pigeons', is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

In the race to describe all of Earth's species before they go extinct it has been suggested that one species that is thriving is taxonomists.

Taxonomists are the people responsible for describing, identifying, and naming species – so far they have described around two million species. This could involve trekking into the jungle to discover new plants and animals but more often means poring over samples in existing collections and databases to unearth previously undescribed species.

'Taxonomic data, knowledge about species, underpins nearly every aspect of environmental biology including conservation, extinction, and the world's biodiversity hotspots,' explains Robert Scotland of Oxford University's Department of Plant Sciences.

If you want to describe all Earth's species before they vanish then the question of the taxonomy community's capacity, and the speed with which they can discover new species, becomes very important.

Some recent studies looking at trends in extinction counted the number of authors on each taxonomic paper and concluded that there was an expanding workforce of taxonomists chasing an ever diminishing pool of undescribed species. 'These findings contradict the prevailing view that there are six million species on Earth remaining to be discovered by an ever diminishing number of taxonomists, the so called 'taxonomic impediment',' Robert comments.

To test whether taxonomists were really a booming or endangered species, and what this might mean for species discovery, Robert and colleagues from Exeter University and Kew Gardens analysed data on the discovery of new plant species. A report of the research is published in the journal New Phytologist.

'What we found was that from 1970 to 2011 taxonomic botanists described on average 1850 new flowering plants each year, identifying a total of 78,000 new species,' Robert tells me. 'But while this period saw the number of authors describing new species increased threefold, there was no evidence for an increase in the rate of discovery.

'One recent idea is that species are becoming more difficult to discover and more authors are subsequently required to put in more effort to describe the same number of new species. We found no evidence for this as the lag period between a specimen being collected and subsequently described as a new species has increased.'

The team's study showed that, far from running out of new species, there are still around 70,000 new species of flowering plant waiting to be discovered. So why are taxonomy authors multiplying?

To get some context the researchers analysed the number of authors on papers in other subjects including botany, geology and astronomy over a similar period, 1970-2013, and then compared them to the data on taxonomy authors.

'We found that the increase in authors on taxonomy papers was in fact fairly modest compared to the 'author inflation' in other subjects including botany,' Robert explains. 'Our data show for geology that there were 1.8 authors per paper in 1975 but this has risen to 4.8 in 2013, and for astronomy, 1.6 authors per paper in 1970, 8.4 in 2013, so a fivefold increase.'

There could be many different reasons for author inflation; more interdisciplinary research, technological advances, the closer monitoring of performance indicators in scientific institutions that has led to the inclusion of students, lab assistants, junior staff and technical staff as authors on papers.

Robert comments: 'Using crude measures of author numbers to measure taxonomic capacity at a time of author inflation across all of science has the potential to be highly misleading for future planners and policy makers in this area of science.

'Our study found that in fact a very large number of new species are discovered and described by a very small number of prolific botanists, and more than 50% of all authors are only ever associated with naming a single species.

'It shows that there remain huge uncertainties surrounding our capacity to describe the world’s species before they go extinct.'

The clocks will be turned back 430 years at Christ Church on Saturday.

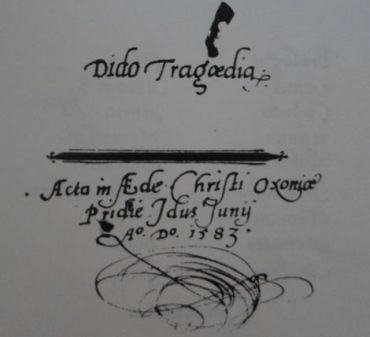

A little-known but fascinating Elizabethan play, rustled up to entertain the Polish ambassador Albert Łaski on his visit to Oxford in 1583, was the inspiration for this weekend's special event.

The evening of drama, served up alongside a banquet in Christ Church hall, is being organised by the University's Early Drama at Oxford (EDOX) project, run by a team of scholars and specialist film-makers.

Central to the sold-out event will be the performance of William Gager's Dido, translated from its original Latin by classicist and English scholar Elizabeth Sandis. The play will be staged in its original venue – once again in front of a representative of the Polish embassy, the Deputy Head of Mission, Dariusz Łaska.

Gager, who was a law student at Christ Church at the time, will be competing for top billing with Christopher Marlowe, whose Dido, Queen of Carthage will also be staged on the night.

Elizabeth Sandis: "We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating"

Elizabeth Sandis: "We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating"And the 16th-century feel will be completed by an authentic Elizabethan banquet, featuring such contemporary delicacies as vegetable and herb soup, roast pork belly with cinnamon gravy, spiced orange and wine jelly, and frumenty, a wheat-based 'porridge' traditionally served with venison or porpoise.

Elizabeth Sandis (pictured above), a DPhil candidate at Merton College specialising in the academic drama of Christ Church and St John’s College in 17th-century Oxford, said: 'We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating. The Christ Church event is the second in our series, after Magdalen last year, and next year we are thinking about a similar event at Merton.

'William Gager got really involved in the drama scene at Christ Church in the 1580s, so when the Polish ambassador was visiting at short notice and they needed to entertain and impress him, Gager was the person they turned to.'

The result was Dido, an adaptation of Virgil's epic Aeneid in the original Latin.

Elizabeth said: 'I've injected a few of the Latin verses back into my translation to give people the chance to hear how it would have sounded in 1583 – iambic senarii and lyric metres, and the Virgilian vocabulary.

'Gager was able to take entire sections of Virgil and incorporate them into his work. It was Elizabethan-style plagiarism but of a wholly acceptable kind because he was able to show off his skills as a Latinist and transpose Virgil's canonical lexicon into something new.

'At the time, everyone would have been familiar with the story of Dido and the fall of Troy, so it was a challenge for the playwright to dramatise that and do something clever with it.'

One example of Gager's playfulness involves a scene in which Aeneas's son, Ascanius, is brooding on the collapse of his home at Troy, having heard his father’s tale of the city’s fall the previous evening at dinner.

Elizabeth said: 'Dido asks him what the matter is, and he replies that he is thinking about his father's story from the night before and is beginning to imagine Troy in the features of a giant pudding on the banquet table – for example, the river Simoeis and the place where the wooden horse was brought in.

'It would have been a large marzipan dessert, and we’ll be recreating it on the night.'

The authentic Elizabethan menu to be enjoyed by the 240 guests was created by Christ Church head chef Chris Simms.

Gager's Dido will form part of a double bill on Saturday, sharing the stage with Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage. Both will be performed by all-male casts, just as they would have been in the late 16th century. Attendees will be able to compare and contrast the two adaptations ahead of a conference, titled 'Performing Dido', to be held by EDOX the following day.

EDOX was formed around 18 months ago by Elizabeth Sandis, Dr James McBain and Professor Elisabeth Dutton, who is directing Dido. The project, partly funded by the British Academy, is undertaking a systematic study of plays written and/or performed in the Oxford colleges between 1480 and 1650.

- ‹ previous

- 178 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools