Features

In the battle against the mosquitoes that carry deadly human diseases scientists are recruiting a new ally: a genetic enemy within the mosquito's DNA.

These new recruits are homing endonuclease genes (HEGs), 'selfish' genetic elements that have a better than normal chance of being passed on between generations despite being potentially harmful to an individual.

HEGs can recognise and 'cut' a short sequence of DNA on one of a pair of chromosomes, then fool an organism's repair mechanism into copying the HEG across onto the other chromosome. The HEG gets inserted within the 'cut' sequence of 'normal' DNA whilst the 'cut' is repaired. It is this 'drive' that makes HEGs particularly interesting for disrupting DNA and hence mosquito control.

Crucially HEGs can be used to recognise and disrupt a bit of DNA that really matters – that is important for an individual mosquito to survive from egg to adult.

'HEGs occur naturally in some simple organisms, such as single-celled fungi, and have been artificially inserted into the genomes of other organisms, notably the mosquito species, Anopheles gambiae, that is the main vector of human malaria,' explains Mike Bonsall of Oxford University's Department of Zoology.

'They can be used either to suppress mosquito populations by altering the inheritance patterns of genes (for example genes that affect survival) or to alter the genetic structure of mosquito populations by driving genes that alter the key mosquito characteristics (such as the ability to transmit a pathogen).'

Such a genetic approach could be an important weapon against diseases like malaria, which is responsible for up to 1.6 million deaths a year worldwide, by reducing the numbers of disease-carrying adult female mosquitoes in a local area to such a level that there aren’t enough to support and pass on the infection to humans.

But HEGs are not simply 'genetic homing missiles' that kill mosquitoes: such selfish genetic elements have to spread, the individuals carrying them have to compete, and populations respond and change.

'While it is necessary to understand the population genetics and patterns of HEG inheritance, the effectiveness of HEGs requires an understanding of both the ecology and genetics. The population dynamics and ecology determine how individuals in a population compete, grow and disperse,' Nina Alphey of Oxford University's Department of Zoology tells me.

'Population genetics might predict that a HEG that reduces survival will naturally spread through a population, but that does not necessarily mean the population will be reduced enough to significantly alter disease transmission. Simply knowing the genetics is not quite enough.'

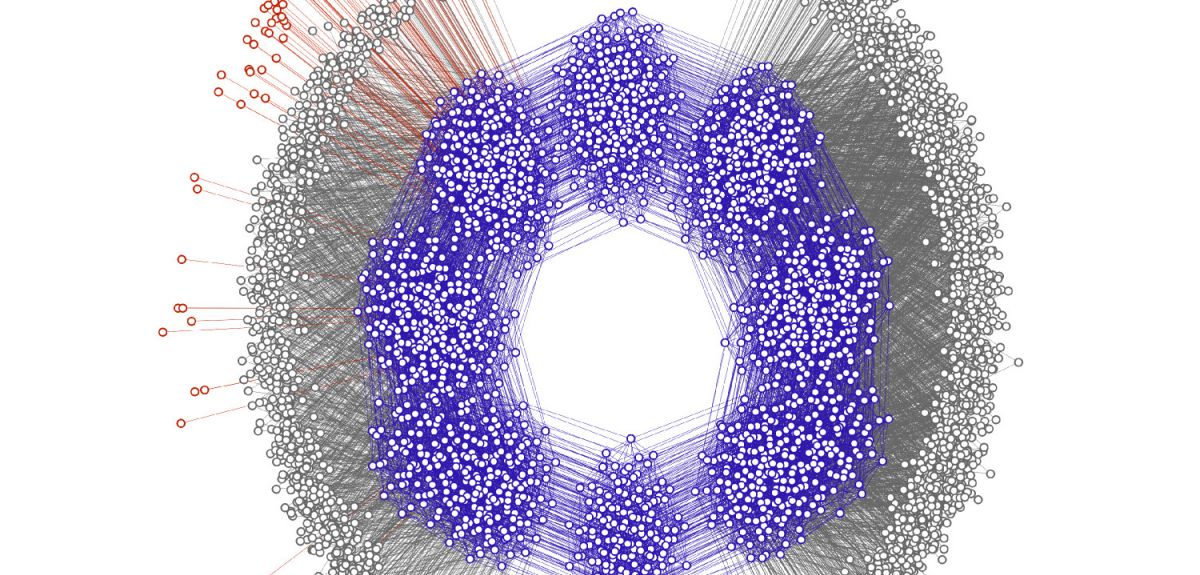

To explore how interactions between ecology and genetics can influence the effectiveness of HEG-based mosquito control Mike and Nina developed a mathematical model as part of a BBSRC-funded project. They report their findings this week in Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

'One significant finding from our work is that we show that the type of competition affects the outcome of HEG-based control. If competition is particularly strong, alterations in early larval survival could lead to an increase in mosquito population size, rather than its decline,' Mike explains. 'This occurs as the population is 'freed' from its natural ecological control – which in mosquitoes occurs in the late-larval stage.

'We also showed that if a HEG does not just reduce the mosquito's survival, but also changes how that mosquito fares during the larval competition, it could achieve a better reduction in mosquito numbers than an identical HEG that simply reduced survival. The effects of a HEG that affects both survival and timing of competition would need to be carefully monitored to ensure that population suppression is achieved.'

Whilst with larger animals it might be possible to monitor individuals as a way of understanding population dynamics this is impractical for populations of thousands of insects, such as mosquitoes, linked to tiny patches of habitat – a small pond or even just a container of water.

Mathematical models are the only practical way of studying the links between genetics and ecology and identifying potential pitfalls in any genetic insect control approach – such as HEGs acting early in an insect's lifecycle being less effective than ones acting later on.

'We are working on extending our modelling approaches to understanding the control of mosquitoes by integrating economics and the cost-effectiveness of control programmes. This involves linking the costs of rearing modified mosquitoes, the epidemiology of the disease, the movement of people and mosquitoes and evaluating the public health benefits,' says Nina. The team have created an online game that highlights some of the issues faced by any control programme.

There are a lot of factors to consider in a future model: another variable is that in the wild populations compete with other species. For instance the malaria-carrying Anopheles gambiae mosquito may compete with various other species, and the dengue-carrying Aedes aegypti and the less competent Aedes albopictus compete with each other in some regions, so that reducing the numbers of one disease-carrying species could boost the numbers of another.

Mike tells me: 'We hope to work out when and where it might be appropriate to combine these insect control strategies with other disease implementation methods (such as vaccination programmes). Also thinking on how these insect control strategies can be used to control the spread of resistance to conventional control programmes is a new BBSRC project we have very recently started.'

A group of Modern Languages students from Oxford University are documenting their time abroad in Brazil via the BBC.

'Para Inglês Ver', or 'For the English to See', is a series of blogs hosted by BBC Brasil that allows the students to share their impressions of the country – from music, arts and culture to race relations and politics – as they travel around during the first few months of 2014.

The blogs are written by Oxford Modern Languages students reading Portuguese combined with another language or other subjects.

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe told Arts at Oxford: 'The project evolved from a series of meetings. I met Juliana Iootty of the BBC during Brazil Week, a cultural event organised by one my tutors, Dr Claire Williams.

'Juliana suggested that some of the Portuguese students should come and visit Broadcasting House, where we were given a tour and talked about potential projects. We then had a second meeting with Silvia Salek of BBC Brasil, who suggested the blog.

'So it was pretty organic, and Juliana and Silvia were both really encouraging and just as enthusiastic about the project as we were.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe said: 'From living with a host family and talking to them, as well as colleagues and friends, I know that the things I've written about will get a debate going among Brazilian people. They're the kinds of topics that come up on the commute to work, or in the staff room, or round the dining table.

'The writing process has been difficult, as there is so much I want to say, with so many subtleties. Writing about social issues for social media is a world away from our 2000-word essays. But it has been great to step out of the books and into the real world.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily Green'The students sometimes move to Brazil with certain preconceptions about the country, and it is always fascinating to see how their views and understanding of Brazilian culture change.

'It will be an opportunity for Brazilians to see themselves through young foreign eyes, and for the students to share what they learn during their time in the country – in terms of both language and culture.

'The BBC Brasil website is an amazing platform for the work of our future Brazilianists.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe said: 'The title is so perfect, really. To get a sense of what it really meant, I would ask people I met what the phrase meant to them. Many people hadn't heard it before but for most it was something false, or something put on just for show.

'In my head I find it easiest to understand it as "sweeping things under the carpet" – not just because you don't want to deal with a problem, but because you don't want anyone to see there is a problem at all.

'So in the first post I was trying to get my head round the title but also highlight a few things I had spied under the metaphorical rug of sunny Brazil – the way there are always two sides to the coin in every aspect of the country. For example, luxury new-age shopping centres sit side-by-side with interior country landscapes that remind me of Nepal; breathtaking natural beauty is coupled with really shocking industrial pollution.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily Green'The Oxford University students taking part in this project are assuming the role of modern travellers who set out to explore Brazil, but instead of explaining it to their fellow countrymen they are talking to a Brazilian audience.

'We hope that this will be a two-way process in which Brazilians can learn from these students' perspectives and perhaps see how they themselves can contribute to a more diverse understanding of their own country.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenWhen you think about evolution, 'survival of the fittest' is probably one of the first things that comes into your head. However, new research from Oxford University finds that the 'fittest' may never arrive in the first place and so aren’t around to survive.

By modelling populations over long timescales, the study showed that the 'fitness' of their traits was not the most important determinant of success. Instead, the most genetically available mutations dominated the changes in traits. The researchers found that the 'fittest' simply did not have time to be found, or to fix in the population over evolutionary timescales.

The findings suggest that life on Earth today may not have come about by 'survival of the fittest', but rather by the 'arrival of the frequent'. The study is published in the journal PLOS ONE and was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

I caught up with the study's lead author Dr Ard Louis, Reader in Theoretical Physics at Oxford University, to find out more.

OxSciBlog: How do your results challenge current popular theory?

Ard Louis: We are arguing that some biological traits may be found in nature not because they are fitter than other potential traits but simply because they are easier to find by evolution. Darwinian evolution proceeds in two steps. Firstly, there is variation: due to mutations, different members of a population may have differences in traits. Secondly, there is selection: if the variation in a trait allows an organism to have more viable offspring, to be 'fitter', then that trait will eventually come to dominate in the population. Traditional evolutionary theory focuses primarily on the work of natural selection. We are challenging this emphasis by claiming that strong biases in the rates at which traits can arrive through variation may direct evolution towards outcomes that are not simply the 'fittest'.

OSB: What can mathematical models tell us about biological processes?

AL: Evolution is perhaps the field of biology where mathematics has been the most successful. For example, it was mathematically trained biologists like R. Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane and S. Wright who first worked out how to combine Mendelian genetics, which Darwin didn’t know about, with Darwinian evolution. Today, very sophisticated population genetic calculations are routinely used, for example, to work out how cancer evolves in a patient’s body.

Of course one always needs to be careful because these models inevitably include simplifying assumptions in order to make them tractable. In our calculations we include difference in rates of the arrival of variation, something not traditionally taken into account in population genetics. But our models so far only apply to fairly simple examples of molecular evolution. Much more work is needed before we could claim that these effects are also important for more complex phenomena such as the evolution of animal behaviour.

OSB: How do your calculations match up with real-world observations?

AL: We predict, for example, that RNA molecules that are more robust to the effect of mutations should naturally arise from our 'arrival of the frequent' effect. RNA can act both as an information carrier and as a catalyst, and so is thought to be very important for the origin of life on earth. It has been known for some time that RNA found in nature is remarkably robust to mutations and we can now provide a population genetic explanation of this phenomenon.

OSB: How have field biologists reacted to these results?

AL: On the one hand, biologists who work on evolution and development have not been so surprised because they have long argued that developmental processes can bias organisms to evolve in certain directions over others. Others have reacted with some caution, which is probably wise given the potentially far-reaching nature of our claims. I think we have raised a lot more questions that we have answered.

OSB: Did the results come as a surprise to you?

AL: On the one hand they didn't, in part because I have long been interested in Monte Carlo simulation techniques which have many parallels to evolution. There, biases in the arrival of variation are well known to affect outcomes. But I was very surprised to find that the biasing effect could be so enormously strong, making it robust to such a wide range of different evolutionary parameters.

OSB: How did your group come to study evolution?

AL: We specialise in statistical physics, and there are many beautiful parallels between evolutionary dynamics and processes in the everyday physical world. In my group we have worked for many years on self-assembly; how individual units can form well-defined composite objects without any external control. Biology is full of amazing self-assembled structures, and so we began asking: how do these structures evolve in the first place?

With the Golden Globes handed out and the Oscars looming, much of the media's attention is focused on the top films of the past 12 months.

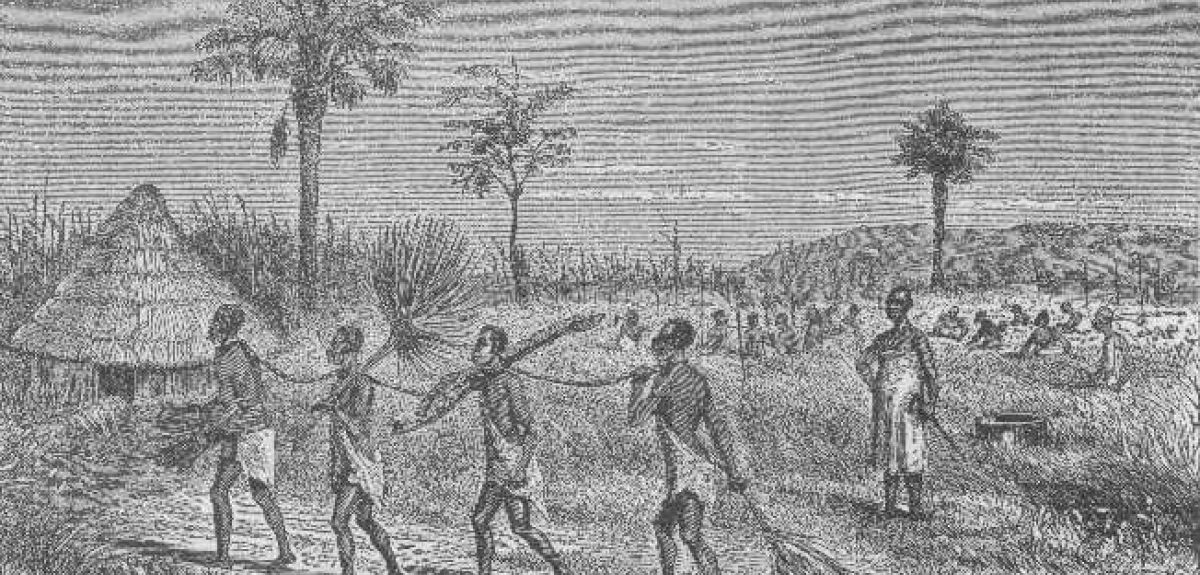

Chief among them is Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave, which has already scooped the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture amid a slew of other nominations and is the hot favourite to triumph at the Academy Awards in March.

The film, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Lupita Nyong'o and Benedict Cumberbatch, is an adaptation of an 1853 memoir by Solomon Northup, a free-born African American from New York who was kidnapped by slave traders.

To coincide with the release of 12 Years a Slave, a BBC Culture Show special, presented by Mark Kermode, looked at the history and culture of slavery.

Oxford academic Jay Sexton, Deputy Director of the Rothermere American Institute (RAI), was one of the experts interviewed for the programme.

He said: 'To be a free black in the northern states would be much better than being a slave in the south, but there would be all sorts of limitations – both legal and political.'

Also interviewed was Richard Blackett of Vanderbilt University, Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at the RAI.

He said: 'Kidnapping was a major issue in mid 19th-century America. One can't quantify how many people were kidnapped, but a considerable number of free black people were kidnapped and sold into slavery.'

The programme can be viewed on BBC iPlayer here (link available until 12:04am, Saturday 1 February).

Leading figures from the arts, science and public policy came together in Oxford last night to discuss the value of the humanities in the 21st century.

Around 450 people packed into the University's Examination Schools to hear the views of, among others, Guardian chief arts writer Charlotte Higgins and Oxford mathematician Professor Marcus du Sautoy.

The event, which included a keynote speech from Dr Earl Lewis, President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, kicked off the Humanities and the Public Good series, organised by The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Among the audience given a warm welcome by the University's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Andrew Hamilton, were a number of school groups from across the UK.

Dr Lewis, in his speech titled 'In Everyone’s Interests: What it Means to Invest in the Humanities', said: 'Three quarters of a century ago, Virginia Woolf posed the question: if you had just three guineas to share, what would you support? In each age we face ostensibly insurmountable challenges that require choices to be made, resources to be allocated and areas to be ignored.

'The American Academy of Arts and Sciences argued in a recent report that we live in a world characterised by change, and therefore a world dependent on the humanities and social sciences.'

Dr Earl Lewis gave the keynote speech

Dr Earl Lewis gave the keynote speechHe added: 'We have to consider that the humanities continue to demonstrate the vibrant and dynamic tension between continuity and change. Longstanding disciplines such as literature, history and philosophy remain important to scholarship and discovery. And for nearly a quarter of a century we have also been embracing interdisciplinary scholarship.

'The humanities give us a fuller understanding of our world – past, present and future. The use of one's precious guineas in support of the humanities must start with a clear sense of its narrative, backed up by data. Investment then follows because the case for support is clear. That is why it is in everyone's interests to support the humanities and the public good – doing so advances our shared future.'

Responding to Dr Lewis's speech, Dame Hermione Lee, President of Wolfson College, Oxford, argued that those defending the humanities should not do so in an 'indignant, embattled or sentimental way'. She added: 'Why should we invest in the humanities? Because we're human.'

Charlotte Higgins, herself an Oxford classics graduate, called for the humanities not to be measured by the same criteria as the sciences, while Professor du Sautoy hailed the value of narrative, storytelling and collaboration in his own discipline.

Nick Hillman, Director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and a late addition to the panel, suggested that humanities scholars need to become better at engaging with policy makers, adding that the humanities have an unfortunate tendency to fight the previous battle rather than the current one.

And in an audience question and answer session chaired by Professor Shearer West, Head of the Humanities Division at Oxford, topics covered included why a sixth former should study a humanities subject at university; the value of longitudinal career studies into humanities graduates; the relationship between humanities study and employment prospects; and funding for the arts and humanities.

Information on the rest of the Humanities and the Public Good series can be found here.

Images: Stuart Bebb (stuartbebb.com)

- ‹ previous

- 175 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools