Features

Margi Blunden, daughter of the First World War poet Edmund Blunden, will be remembering her father and his work at the WW1 Poetry Spring School run by Oxford University's English Faculty on 3-5 April 2014.

Margi will recall life growing up with a father deeply affected by the Great War and shed light on his literary achievements. As our living link to this bygone age, Margi will provide a thrilling insight into the man who wrote the autobiographical Undertones of War (1928), hailed as Blunden's greatest contribution to the literature of war.

The Spring School is open to members of the public, particularly those who are seeking to challenge common misconceptions and gain a deeper critical appreciation of Great War poetry. It will bring together world-leading experts, each giving an introductory lecture on the major poets and poems. Speakers will provide reading lists and follow-up exercises for further study.

Other speakers confirmed include: Adrian Barlow, Meg Crane, Guy Cuthbertson, Gerald Dawe, Simon Featherstone, Philip Lancaster, Stuart Lee, Jean Liddiard, Alisa Miller, Charles Mundye, Jane Potter, Mark Rawlinson and Jon Stallworthy.

Aged 19, Edmund Blunden volunteered to join the army, despite winning a place at The Queen's College, Oxford to read Classics. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and went to France in early 1916 and was eventually demobilised in mid-February 1919. During his service in France and Flanders he spent two years at the front, more than any other well-known war writer. Those two years included some of the most violent and bloody fighting in the war, including the battle of the Somme and the battle of Third Ypres.

His most famous works also include In Concert Party: Busseboom (written 10 years after the war) and The Waggoner (1920). He enjoyed a productive career as an editor, journalist, critic and biographer. Blunden was also instrumental in bringing the works of the war poets Wilfred Owen and Ivor Gurney to publication. Edmund Blunden died at his home on 20 January 1974 aged 77.

The Spring School will be held at the Faculty of English, St Cross Building, University of Oxford on 3-5 April 2014. There are a number of different ticket options, including student, senior, school and single-day rates. See the website for full details.

To commemorate the centenary of the First World War, the Oxford English Dictionary is seeking earlier or additional evidence for a host of WWI-related vocabulary, including 'shell shock', 'demob', 'skive' and 'Sam Browne'. In a guest blog post, Kate Wild, senior assistant editor of the OED, explains further...

The Oxford English Dictionary needs you!

Can you help find earlier evidence for the use of some wartime words?

To commemorate the centenary of the start of the First World War, the OED is updating its coverage of terms relating to or coined during the war.

The First World War had a significant impact on English vocabulary: new words were needed to refer to, for example, new vehicles, weapons, military strategies and trench-related illnesses; words were borrowed or adapted from other languages, especially French and German; and many soldiers’ slang terms were either coined or widely popularized.

For many of these terms, our first quotations are from newspapers and magazines, and we know that there may well be earlier evidence – especially for slang and colloquial terms – in less easily accessible sources such as private letters and diaries.

And just last month, the National Archives released a set of digitized war diaries which might contain valuable evidence of WWI-related vocabulary.

The OED has a long tradition of asking the public to help find evidence of word usage.

Back in the 19th century, the first editor of the OED, James Murray, published lists of words for which he wanted to find earlier or additional evidence, and this type of appeal has continued in recent years, first with the television programme Balderdash & Piffle, and more recently with the OED Appeals website, oed.com/appeals.

Although OED readers and researchers consult a large number of books, newspapers, and online databases, it would be impossible to read or search everything that has ever been written in English.

And given that the purpose of the OED is to show the history of each word in English, the earliest written evidence of a word is very important.

As an example, one of our appeals is for earlier evidence of the term shell shock, for which our earliest quotation is currently the title of a 1915 medical article, ‘A contribution to the study of shell shock.’

This article was written by Charles Samuel Myers, a psychologist who was commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps during the First World War.

Some accounts, though, suggest that Myers did not invent the term, but merely popularized it.

Certainly, shell shock sounds like a term that might have been devised by laymen rather than by a medical practitioner, and it is possible that Myers heard it being used by soldiers at the front.

Any earlier evidence of such usage – perhaps from a soldier’s letter or diary – would contribute to our understanding of the term.

A more light-hearted example is the colourful phrase Zeppelins in a cloud or Zepps in a cloud (sometimes also Zeppelins/Zepps in a fog/smokescreen and other variants), meaning ‘sausage and mash’.

Our first example at present is from a 1925 dictionary, Soldier & Sailor Words.

Given that this is a dictionary of slang terms used in the First World War, it seems highly likely that earlier evidence can be found.

This appeal has elicited a number of responses, with suggested quotations from as early as 1915 – though it is possible that there might be something even earlier out there.

For all our appeals, we check the suggested quotations to make sure they are accurate and correctly dated.

The earliest valid quotation is then added to the dictionary entry when it is published in its revised form.

The OED Appeals website always acknowledges those who have submitted usable and verifiable evidence.

The full list of WWI-related appeals can be found at oed.com/appeals.

If you think you might be able to help, please have a look and send in your evidence!

The revised WWI-related vocabulary will be published on OED online during the centenary period.

Particular smells can be incredibly evocative and bring back very clear, vivid memories.

Maybe you find the smell of freshly baked apple pie is forever associated with warm memories of grandma's kitchen. Perhaps cut grass means long school holidays and endless football kickabouts. Or maybe catching the scent of certain medicines sees you revisit a bout of childhood illness.

What's remarkable about the power of these 'associative memories' – connecting sensory information and past experiences – is just how precise they are. How do we and other animals attach distinct memories to the millions of possible smells we encounter?

There's a clear advantage in doing so: accurately discriminating smells indicating dangers while making no mistakes in following those that are advantageous. But it's a huge information processing challenge.

Researchers at Oxford University's Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour have discovered that a key to forming distinct associative memories lies in how information from the senses is encoded in the brain.

Their study in fruit flies for the first time gives experimental confirmation of a theory put forward in the 1960s which suggested sensory information is encoded 'sparsely' in the brain.

The idea is that we have a huge population of nerve cells in many of our higher brain centres. But only a very few neurons fire in response to any particular sensation – be it smell, sound or vision. This would allow the brain to discriminate accurately between even very similar smells and sensations.

'This "sparse" coding means that neurons that respond to one odour don't overlap much with neurons that respond to other odours, which makes it easier for the brain to tell odours apart even if they are very similar,' explains Dr Andrew Lin, the lead author of the study published in Nature Neuroscience.

While previous studies have indicated that sensory information is encoded sparsely in the brain, there's been no evidence that this arrangement is beneficial to storing distinct memories and acting on them.

'Sparse coding has been observed in the brains of other organisms, and there are compelling theoretical arguments for its importance,' says Professor Gero Miesenböck, in whose laboratory the research was performed. 'But until now it hasn’t been possible experimentally to link sparse coding with behaviour.'

In their new work, the researchers demonstrated that if they interfered with the sparse coding in fruit flies – if they 'de-sparsened' odour representations in the neurons that store associative memories – the flies lost the ability to form distinct memories for similar smells.

The flies are normally able to discriminate between two very similar odours, learning to avoid one and head for the other. This is controlled by the neurons that store associative memories, called Kenyon cells. There's a separate nerve cell that acts as a control system to dampen down the activity the Kenyon cells, preventing too many of them from firing for any particular odour.

Dr Lin and colleagues showed that if this single nerve cell is blocked, the odour coding in Kenyon cells becomes less sparse and less able to discriminate between smells. The flies end up attaching the same memory to similar, yet different, odours.

Sparse coding does turn out to be important for sensory memories and our ability to act on them. Although the research was carried out in fruit flies, the scientists say sparse coding is likely to play a similar role in human memory.

Although sparse coding in the brain would seem to require much greater numbers of nerve cells, that cost appears to be worth it in being able to form distinct associative memories and act on them – thankfully. A life of experiences and memories is so much more full as a result.

Chemistry probably isn't the first thing that comes to mind when you see skeletons at a museum, but an understanding of chemical reactions is essential to the work of the modern museum conservator.

Bethany Palumbo, Conservator for Life Collections in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, used her chemical expertise to restore centuries-old whale bones for the Museum's recent reopening. The fruits of her team's hard work are now on display for all to see at the Museum, which reopened on 15 February to a staggering 30,000 visitors in the first week alone.

'Chemistry is a key element of conservation,' says Bethany. 'When I began the whale project in mid-2013, there had been no documented preparation of the skeletons for over a century – some of them have been at the Museum since 1860! We had to examine every inch of each whale and research the chemical composition of their bones and the oils they secrete before deciding how to proceed.'

Cleaning and preserving old bones is an intricate, technical task and each treatment must be tailored to the individual bone. Whale bones are especially challenging, as fatty oils slowly seep out over the years.

'When we began the project, there were thick layers of oxidised natural oils on many of the bones,' says Beth. 'This unsightly residue not only attracts dust and makes specimens look dirty, but it is also acidic in nature so can damage the bone. When we tested the oils, they had an acidity of pH4 – about the same as most acid rain. The density of the oil varied across the specimens, and the skulls tended to have more oil than other areas. Whales have a hollow area in front of their skulls filled with oil to focus sonar signals which seeps into the bones where it can remain for centuries after they die. Areas of bone, still saturated with this acidic oil, were in some cases crumbling with a gritty texture similar to wet sand.'

To remove the oily secretions, Bethany and her team brushed solutions of ammonia and purified water onto the bones. Ammonia is an alkaline chemical that works by a process known as saponification that converts fats into soap. Ammonia breaks fat molecules up into their glycerol and fatty acid elements to produce soluble salts and soap scum, which can simply be wiped or vacuumed from the surface. Concentrations of ammonia varied depending on the areas being treated.

'Particularly oily areas, such as the humpback skull needed to be treated with 10% ammonia, whereas we used only 5% for the other specimens,' explains Beth. 'We were careful when the solution came into contact with the cartilage, as this can also disintegrate with the alkaline ammonia solution. There's always a balance to strike with conservation, the treatment method you choose on should never cause more harm than good.'

As well as damaging the bones, the acidic oil also caused verdigris – the green pigment currently coating the Statue of Liberty – to blossom from the copper wires inside the bones used to support the skeletons. Verdigris can be build up over time when copper reacts with oxygen, and is rapidly accelerated by acids.

'The verdigris on the copper wires was exploding from the drilled holes in the bone, causing the wires to weaken and snap when we tried to remove them,' says Beth. 'We ended up using a soldering iron to heat the wire, softening the surrounding cartilage just enough for us to pull the wires out and then vacuum out any residues.

'We have now replaced the wires with stainless steel, which is strong and resistant to the environmental conditions of the museum. We considered alternative methods of putting the skeletons back together, but it made more sense to use the existing holes in the bones to avoid creating further damage to the skeletons.'

Almost paradoxically, the conditions of the Museum environment are actually rather bad for the bones. Ultraviolet sunlight from the glass ceiling destroys collagen in the bones, weakening their structure, and the fluctuating temperatures cause the bones to expand and shrink, weakening joints. Before the roof was repaired, the fluctuating humidity worsened this problem.

'Technically, the best place for these bones would be a cool, dark room,' explains Beth. 'There is often a trade-off between conservation and education, so we have to do the best we can to make sure the skeletons can cope when out in the open for all to see. The adhesives we select, for example, have to be able to withstand high heats and fluctuating temperatures.'

Finally, when reconstructing the skeletons during the restoration process, the team tried to correct the anatomical features of the whales where possible.

'Dried cartilage will shrink over time, pulling the bones into unnatural positions,' says Beth. 'We corrected this by repositioning bones with new wires where possible, but some areas were just too fragile. Also, since we only had six months to complete the project, we simply didn't have the time to correct everything. There are some parts of the fins and ribcages that remain slightly incorrect, which is frustrating, but the skeletons are still far more anatomically correct than when we started.

'After a thorough restoration project, I think our whales will have a few good decades more on display. I'm extremely proud of what my team achieved in a short space of time, and hope that visitors will continue to enjoy seeing the whales in the Museum for years to come.'

The conservation treatment of the whale bones was documented in real time at the Once in a Whale blog, where you can learn more about the whole process.

Love is in the air for many of us today – but it's always a time for romance at the Ashmolean Museum, which has been featuring a number of Valentine's Day-themed works of art from its collections on its Twitter feed throughout the day.

Two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Kasaya Sankatsu

Two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Kasaya SankatsuUtagawa Kunisada (1786–1864)

Woodblock triptych print, c. 1849

Here, two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Sankatsu. Sankatsu holds the two halves of a red sake cup in her hands, demonstrating her divided loyalties towards the two men.

The Love Letter

The Love LetterThomas Sully (1783–1872)

Oil on canvas, 1834

One of Sully's most popular compositions, of which he painted numerous replicas. This version was presumably bought by the tenor Joseph Wood and his wife, the soprano Mary Ann Paton, during their American tour in 1836 when Sully painted Mary Ann's portrait, or perhaps when Sully visited England to paint Queen Victoria in 1837.

Acme and Septimius

Acme and SeptimiusFrederic Lord Leighton (1830–1896)

Oil on canvas, 1868

The subject of this scene of idyllic love is taken from Catullus, Carmine XV. Both the round shape and composition are indebted to Raphael's Madonnas. The background includes the rose, traditionally the symbol of love, and orange trees. When it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1868, it was praised by critics, who noted with approval Leighton's chaste treatment of the scene.

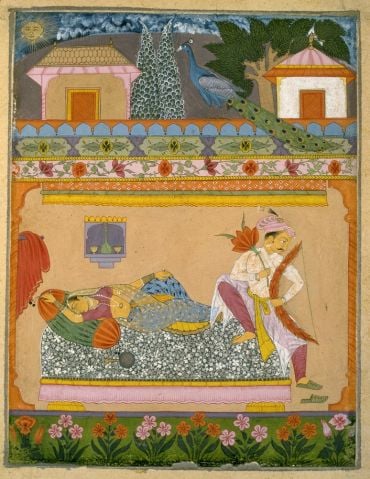

Lovers at dawn, illustrating the musical mode Raga Vibhasa

Lovers at dawn, illustrating the musical mode Raga VibhasaNorth Deccan, India

Gouache on paper, c.1675

The musical mode Vibhasa ('radiance') is normally performed at dawn. It is conceived pictorially as a noble couple who have passed the night together. Often, as the lady sleeps, her lover may aim his bow to shoot the crowing cock. But here he holds a flower bow and arrow like the love god Kama, and the peacock is unthreatened. Ragamala painting became a highly popular genre in the Mughal period.

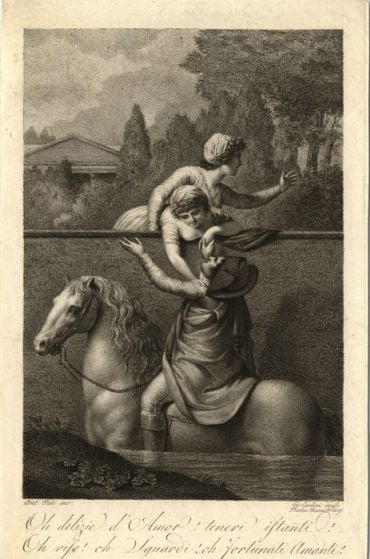

Oh delizie d'Amor!

Oh delizie d'Amor!Giovanni Cardini after Antonio Fedi

Etching and stipple, c.1810-20

An element of drama, and plenty of exclamation marks, are all provided by this Italian scene of elopement.

Love bringing Alcestis back from the Grave

Love bringing Alcestis back from the Grave

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones

Watercolour and chalk on paper, 1863

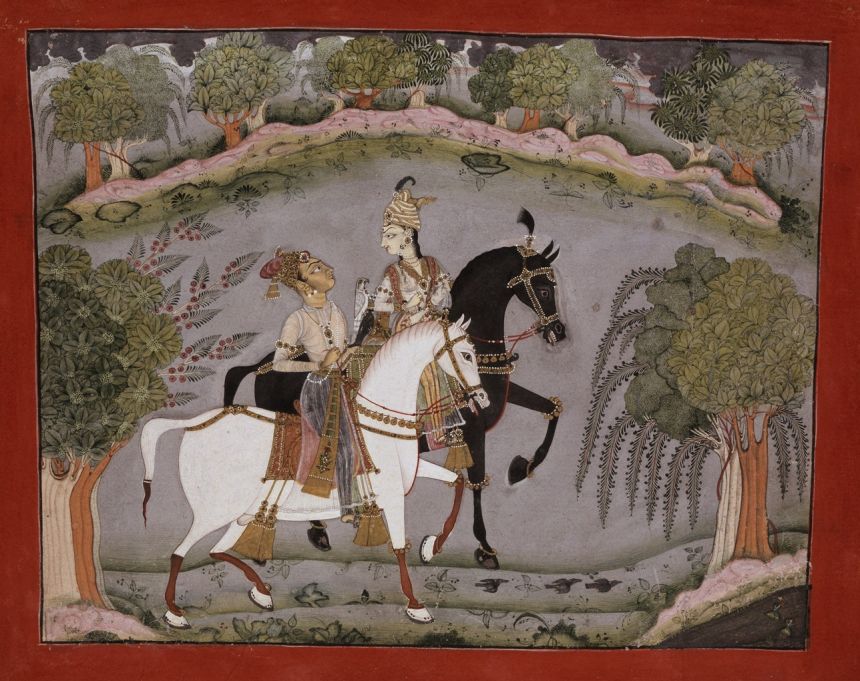

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati

Kulu, northern India

Gouache with gold and silver on paper, c.1720

A cultivated prince and gifted singer, the Muslim Sultan Baz Bahadur, Sultan of Malwa, was devoted to the company of musicians and dancing girls. His favourite was Rupmati, a celebrated beauty who became his constant companion. The love of Baz Bahadur and his Hindu mistress became a popular theme of poetry and song in late Mughal India.

All images copyright Ashmolean Museum.

- ‹ previous

- 174 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools