Features

These drugs were handed out via a phoneline during the swine flu pandemic of 2009 as part of a wider public health strategy.

Professor Carl Heneghan of Oxford University's Department of Primary Care Health Sciences and colleagues in the independent Cochrane Collaboration are clear that the money was wasted. They argue that the decision to stockpile the drugs might have been different had we had access to all the clinical data on their effectiveness.

Now we do have that evidence, and Carl says: 'There is no credible way these drugs could prevent a pandemic.' Speaking at a media briefing at the Science Media Centre in London, he said the money spent on stockpiling had been 'thrown down the drain'.

Since 2009, the Cochrane researchers have had a long running battle with the drug firms that manufacture Tamiflu and Relenza (Roche and GSK, respectively) to get unconditional access to their full data. They finally received everything last year, after first GSK then Roche said they would provide the materials – a significant development in the campaign to increase openness and accessibility of complete trial data.

The Cochrane group has been significant players, along with the AllTrials campaign, the BMJ medical journal, Ben Goldacre and others, in changing the whole approach to this issue among researchers, journals, drug firms and regulators. The simple argument is that if we are to make the right decision on what are the best drugs – considering their safety, effectiveness and the balance of benefits they offer in treating conditions over their side-effects – we need to have all the evidence available.

The researchers have now made that assessment for Tamiflu in the prevention and treatment of flu. They have reviewed a phenomenal amount of material, and with the BMJ and the Cochrane Collaboration, have published their conclusions today. They call on government and health policy decision makers to review guidance on the use of Tamiflu in light of their new evidence.

They found that Tamiflu is effective – but it shortens symptoms of flu by only around half a day on average. And importantly, they say, there is no good evidence to support claims that it reduces complications of influenza or admissions to hospital.

Then there are the side effects. Using Tamiflu to treat flu, the evidence confirms an increased risk of suffering from nausea and vomiting.

When Tamiflu is used to prevent flu, the drug can reduce the risk of people suffering symptomatic influenza. But there was an increased risk of headaches, psychiatric disturbances, and kidney events.

The review authors, Drs Tom Jefferson, Carl Heneghan and Peter Doshi, conclude that there are insufficient grounds to support the stockpiling of Tamiflu for mass use in a pandemic. From the best conducted randomised trials, there just isn’t enough evidence on the crucial elements of reducing serious complications of flu that can lead to hospitalisation and death, and the prevention of spread of flu. On the other hand we know there would be side-effects.

Not all scientists agree on the assessment of the balance of benefits of these antivirals versus their side-effects. Virologist Professor Wendy Barclay at Imperial College London believes the shorter time that symptoms last is important: 'Although one day does not sound like a lot, in a disease that lasts only 6 days, it is…We have only two drugs with which we can currently treat influenza patients and there is some data to suggest they can save lives. It would be awful if, in trying to make a point about the way clinical trials are conducted and reported, the review ended up discouraging doctors from using the only effective anti-influenza drugs we currently have.'

Roche, the manufacturers of Tamiflu, fundamentally disagree with the overall conclusions of the Cochrane review and criticised some of the report’s methodology. In media reports, UK Medical Director Dr Daniel Thurley has said: 'Roche stands behind the wealth of data for Tamiflu and the decisions of public health agencies worldwide, including the US and European Centres for Disease Control & Prevention and the World Health Organisation.'

Indeed, Roche have pointed to a large observational trial in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine that they funded which recently reported a reduction in deaths among those hospitalised with swine flu H1N1, though there are some who disagree with that analysis too.

So what to make of all of this? An editorial in the Guardian concludes: 'The only way to resolve the argument is proper science. That means transforming clinical trials, harmonising the way they are carried out. It has happened with malaria drugs, and it is happening with HIV. The industry must allow access to their data. Confident that like is compared with like, trials can then be subjected to meta-analysis, allowing statisticians to drill down into sub-populations to establish when a drug performs most effectively.'

The editorial points to the need to be able to react swiftly and carry out good research actually during pandemics, as former Oxford University professor and now director of the Wellcome Trust, Jeremy Farrar, argued in the paper last month.

What has really changed is the ability to have these discussions based on all of the evidence. There is a real shift in the level of scrutiny and the analyses that are now possible with access to all clinical trial data (although dealing with all these reams of data also brings new challenges too). That is a phenomenal change and a real achievement by the Cochrane researchers.

David Spiegelhalter, Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge, comments: 'This is a ground-breaking review. Since important studies have never been published, the reviewers have had to go back to clinical trial reports comprising over 100,000 pages: the effort to obtain these is a saga in itself. The poor quality of these reports clearly made extracting relevant data a massive struggle, with many pragmatic assumptions having to be made, but the final statistical methods are standard and have been used in hundreds of Cochrane reviews. Let’s hope that in future high-quality data can be routinely obtained and this type of review becomes unnecessary.'

It was one of the biggest protest movements ever seen in the UK.

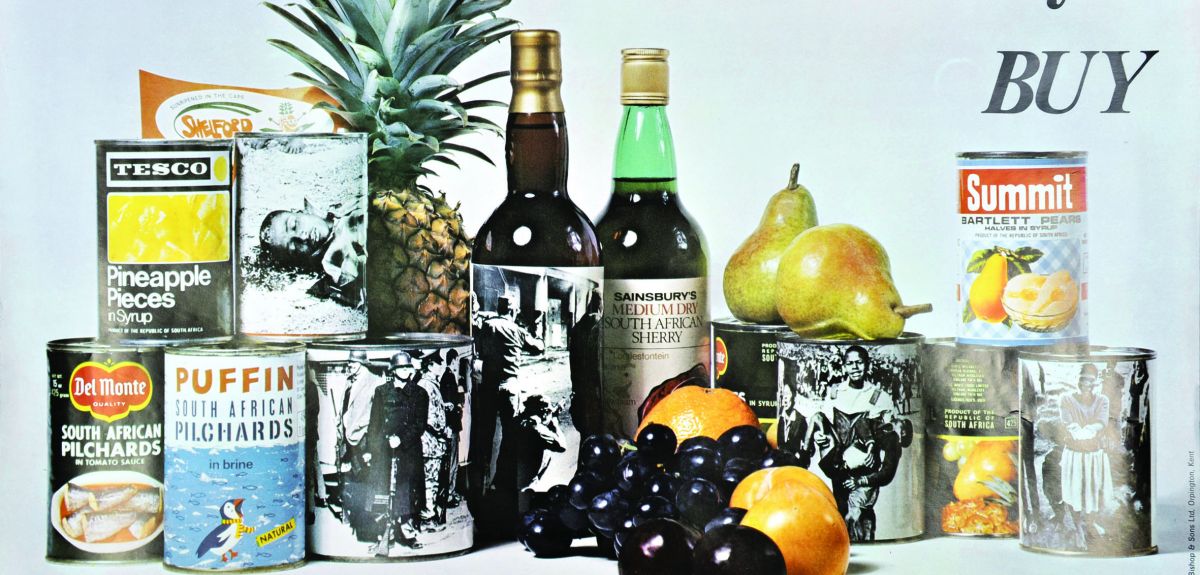

For three decades, the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) campaigned for a boycott of apartheid South Africa and supported all those struggling against it.

Founded in 1959 as the Boycott Movement, the AAM grew into the biggest ever British pressure group on an international issue.

Now, 20 years after Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa's first black president, a collection of rare documents held by Oxford University's Bodleian Library has been uploaded to a new website chronicling the history of the AAM.

Lucy McCann, archivist at the Bodleian Library of Commonwealth and African Studies at Rhodes House, said: 'The Anti-Apartheid Movement Archive at the Bodleian Library records the activities of one of the most important campaigning organisations in post-war Britain and this website makes available to all a wide selection of documents, posters, photographs, newly recorded interviews, videos and other items.

'It is of interest to those studying South Africa and British-South African relations over the period and the activities and effectiveness of campaigning organisations.'

The new website features three decades' worth of videos, photos, posters and documents relating to the AAM. Highlights include footage of the Nelson Mandela tribute concert at Wembley in 1988, iconic posters from campaigns to save those accused at the Rivonia Trial from the gallows in 1964 and to stop the Springbok cricket tour in 1970, and letters from Margaret Thatcher arguing against sanctions on South Africa.

There are also interviews with musician Jerry Dammers of The Specials, actor Louis Mahoney, David Steel (AAM President in the 1960s), and grassroots activists who talk about what motivated them to get involved and help bring down South Africa's system of white minority rule and racial segregation.

Ms McCann added: 'I think the archive is very important because for people at school now, all this happened before they were born.

'But it was a very big movement in Britain and some of the events they organised, such as the Nelson Mandela concert, were global events and were broadcast around the world.'

The website is part of a wider education project that includes a pop-up exhibition with 22 display boards on anti-apartheid campaigns and support groups.

The project is funded by the Barry Amiel & Norman Melburn Trust and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Leading figures from the worlds of art, museums, film and historiography will visit Oxford next month in the latest series of Humanitas events.

World-renowned artist Vik Muniz will deliver a series of stimulating talks in his role as Humanitas Visiting Professor in Contemporary Art. Mr Muniz is a photographer who incorporates unusual materials into the photographic process. For his recent project Pictures of Garbage he created a series of monumental photographic portraits made from industrial rubbish in collaboration with the litter pickers of Jardim Gramacho, one of the largest landfill sites in Latin America.

Mr Muniz will be joined for a symposium titled 'Between the Artist and the Museum' by Michael Govan, Humanitas Visiting Professor in Museums, Galleries and Libraries. Mr Govan is CEO and Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and is responsible for turning it into Southern California's dominant cultural organisation.

Also visiting Oxford next term are filmmaker Kelly Reichardt and historiographer Professor Lynn Hunt.

Ms Reichardt, Humanitas Visiting Professor in Film and Television, will be giving a masterclass and taking part in an 'in conversation' event, while Humanitas will also be hosting special screenings of her films Meek's Cutoff and Wendy and Lucy.

Professor Hunt will deliver a series of lectures on 'Dilemmas of History in a Global Age', which will conclude with a roundtable discussion with Professor Lyndal Roper and Professor Elleke Boehmer.

Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities.

Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue with the support of a series of generous benefactors and administered by the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

In a remote semi-desert region of South Africa, the Karoo veld, what looks like a huge satellite dish has risen up to dominate the landscape.

But instead of tuning into TV this dish is the first part of a giant radio telescope called MeerKAT that will play a key role in the creation of the world’s largest telescope, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).

Last week saw the official launch of this first dish of many, I asked Matt Jarvis of Oxford University's Department of Physics, one of the Oxford scientists involved in MeerKAT, about plans for the new telescope and where it will lead…

OxSciBlog: What is MeerKAT and why is it important?

Matt Jarvis: MeerKAT is actually made up of 64 dishes, each 13.5m in diameter. All of these dishes are connected to make up a single telescope that operates at radio wavelengths (around medium-wave for the people who still have analogue radios), much like a satellite dish but rather than receiving information from satellites it detects radio waves from astrophysical phenomena such as jets emanating from around black holes and sites of star formation. It is the precursor to the Square Kilometre Array which will extend MeerKAT from 64 to 254 dishes in around 2020, making it much more powerful.

OSB: What questions will MeerKAT investigate?

MJ: MeerKAT will detect radio waves from the distant reaches of the cosmos. It allows us to trace a range of physical processes that occur in the Universe, such has high-speed jets (moving at close to the speed of light) which arise from accretion around black holes, both in our own galaxy and from supermassive black holes in the centres of distant galaxies. It will also be able to detect neutral hydrogen gas, the fundamental building block of all the things that we can see in the Universe, from stars to galaxies, enabling us to determine how this gas gets turned into stars over the history of the Universe. By using the radio emission from these distant galaxies we will also be able to investigate the impact of Dark Energy and Dark Matter in the Universe and how these may evolve, possibly leading us to reassess how gravity acts on very large scale.

OSB: How are Oxford scientists involved in the project?

MJ: Oxford has a large involvement in MeerKAT. Two of the Large Surveys to be undertaken on MeerKAT are co-led by Oxford staff. I’m the co-PI of the deep radio continuum survey (MIGHTEE) to study how galaxies evolve over the history of the Universe and Rob Fender is the co-PI of the THUNDERKAT survey which aims to detect all of the phenomena which go bang, such as stars colliding together, bursts of radiation when a star dies and accretion events on to a black hole. We have also been involved in some of the technical development for the receivers on the dishes.

OSB: How will work with MeerKAT feed into SKA?

MJ: MeerKAT is essentially a stepping stone to the SKA, in terms of both science and engineering. The work we will do will set the stage for the SKA to really move us forward into a whole different regime of radio astronomy. MeerKAT will be a fantastic facility in its own right, providing us with the most sensitive radio surveys in the southern hemisphere, however, the SKA will be able to take such surveys and expand them by an order of magnitude in sensitivity and ability to map large volumes of the Universe. From a more technical perspective, the lessons learned from constructing MeerKAT will feed into the design specifications of the SKA, and will also mean that we can test new algorithms to turn the raw data into scientifically useful maps and catalogues for use throughout the community.

OSB: What are the challenges of dealing with data from MeerKAT/SKA?

MJ: The main challenges are the sheer data volume that we need to handle. For example, we are unable to store the raw data coming from the telescope, and have to reduce it very quickly in order to keep up with the observations. This requires a large effort in data transport, supercomputers and having the necessary computer code to handle the data effectively.

OSB: What is the next big milestone in MeerKAT's progress?

MJ: The next big milestone will be when there are 16 dishes on the ground and all hooked up. This will then enable us to start carrying out the science, before the whole 64 dishes are in place. This is something quite unique to radio astronomy, in that we don't need the whole telescope to start doing some of the science.

Do males have more to gain than females from mating with additional partners?

The theory that they do, and that this can help to explain different sex roles observed in the males and females of many species, is known as 'Bateman's principles', named after the work of English geneticist Angus John Bateman.

In a recent study reported in Proceedings of the Royal Society B a team, led by Oxford University researchers, investigated Bateman's principles in relation to populations of red junglefowl (Gallus gallus), the wild ancestor of the domestic chicken.

'Bateman's principles state that males are more variable than females in the number of offspring they produce and number of sexual partners,' explains Dr Tom Pizzari of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, one of the research team. 'This leads to a stronger relationship between number of offspring and number of partners in males than in females. In other words, males gain more reproductive success by mating with additional partners than females do.

'This difference is explained by the fact that males produce orders of magnitude more sperm than there are eggs available for fertilisation, so their reproductive success is strongly limited by female (egg) availability. Females on the other hand tend to produce a smaller number of larger eggs, and generally mating with additional males does not influence the number of eggs that a female can afford to produce.'

To test the principles the team studied groups of red junglefowl and carefully recorded all mating events and assigned parentage to every offspring produced. They then ran experiments to test the relationship between reproductive and mating success.

'Studying Bateman's principles properly presents many challenges,' Tom tells me. 'First, detailed information on mating success (who mates with whom) is required. Previous studies did not measure mating behaviours, but simply inferred who mates with whom based on parentage of the offspring. This approach however, misses out all those mating events which failed to result in fertilisation.

'Second, Bateman's principles are concerned with how males increase their reproductive success by mating with additional females. However, there are other pathways through which males can increase the number of offspring sired: mating with particularly fecund females, and defending their paternity in sperm competition. Again, most studies so far have explored Bateman's principles without controlling for these alternative pathways.

'Finally, one must be very careful about how to interpret a positive relationship between reproductive success and mating success in females. One possibility is that females genuinely increase the number of offspring produced by mating with additional males, another is that females that are inherently more fecund are more attractive to males and so end up with more partners.'

The new study showed that in failing to address these challenges traditional approaches can lead to very drastic biases in estimating Bateman's principles and that future research in this area should combine independent data on mating behaviour, multivariate statistics, and experimental tests.

'Our results suggest that once these biases are controlled for, Bateman was essentially correct: males gain more reproductive success by mating with additional partners than females, however these sex differences are much smaller than estimated by traditional methods,' Tom comments.

'This means that males are more strongly selected to compete over access to mates than females, explaining why sexual selection is typically more intense in males, providing an answer to Darwin's original question of why it is males that often display more exaggerated traits in a species.'

- ‹ previous

- 172 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools