Features

Birds previously identified as having a 'bold' personality return to their nests more rapidly after being faced with a threat than their 'shy' counterparts.

The finding comes from a study of wild great tits in Oxford's Wytham Woods which recorded the responses of 43 female great tits to a simulated threat during the breeding season and then compared the time it took for birds with shy or bold personalities to return to incubate their eggs.

A report of the research, undertaken by Ella Cole of Oxford University's Department of Zoology in collaboration with John Quinn, is published today in Biology Letters. I asked Ella about shy and bold birds, taking risks, and where personality and ecology collide…

OxSciBlog: How do you determine if birds have a 'shy' or 'bold' personality?

Ella Cole: We measure personality by temporarily taking birds into captivity and releasing them into a room containing five artificial trees. We then record how they explore this new space for eight minutes using a handheld computer.

Birds vary considerably in their behaviour in this test, with some bold individuals quickly exploring every corner of the room, and other, more cautious birds staying in one place for the majority of the test. If individuals are tested again, weeks, months or even years later, they tend to behave in a similar way.

Previous work in captivity has shown that great tits that explore more quickly in this test are also more aggressive, less wary of novel objects and more likely to take risks than slower exploring birds. We therefore use this test as a measure of 'boldness'.

OSB: How did you test the link between personality and risk-taking behaviour?

EC: We wanted to measure risk-taking behaviour in the context of reproduction to test whether bold and shy birds differed in the amount of risk they will take to protect their offspring. Birds are very vigilant for any potential threats at their nest which may endanger themselves or their young.

We measured risk-taking by attaching a small black and white flag, representing an unknown threat, to the roof of birds' nestboxes and recording the time it took for females to return to the nest and resume incubating their eggs. We then tested whether the time it took a bird to re-enter the nestbox could be predicted by their personality score.

OSB: What did your experiments reveal about this link?

EC: We found that relatively bold females were quicker than shy birds to resume incubation in the face of perceived risk, with some shy females not returning until the flag was removed. Although it is not known how long these birds would have stayed away if the threat had not been removed, we do know that tits can abandon their breeding attempts completely in response to novelty at the nest.

Our results therefore suggest that shy individuals may prioritise their own survival over that of their offspring, while bold birds do the opposite. These findings support the idea that different personalities may reflect different approaches to life, where bold individuals adopt a 'live fast, die young' strategy, while shy individuals are more cautious and reserve more of their resources for the future.

OSB: Why is understanding birds' personalities important for ecology/conservation?

EC: The existence of animal personalities has wide reaching implications for the study of ecology and evolution. The environment an individual experiences in its life - both in terms of habitat and who it interacts with - is largely determined by its behaviour. Personality has been linked to a wide range of important behavioural traits such as dispersal, habitat choice, social behaviour, feeding, and mate choice.

As a consequence knowledge of personality can help scientist understand how species invade new habitats, how information or diseases spread through groups of animals, the stability and growth rates of populations and ultimately how behaviours evolve. Knowledge of personality even has implications for conservation; in many species personality is related to reproductive success, meaning that conservation breeding programmes can target individuals with certain personality types.

OSB: How do you hope to explore birds' personalities in future research?

EC: One area we hope to explore further is how shy and bold personality types might differ in how they find food in the wild. Work in captivity suggests that shy individuals may be more thorough when searching for food, while bold animals search more quickly but also more superficially. However, very little is known about how personality influences natural foraging behaviour, despite the fact that foraging performance is well known to influence both survival and reproduction, and is therefore a likely mechanism linking personality to fitness.

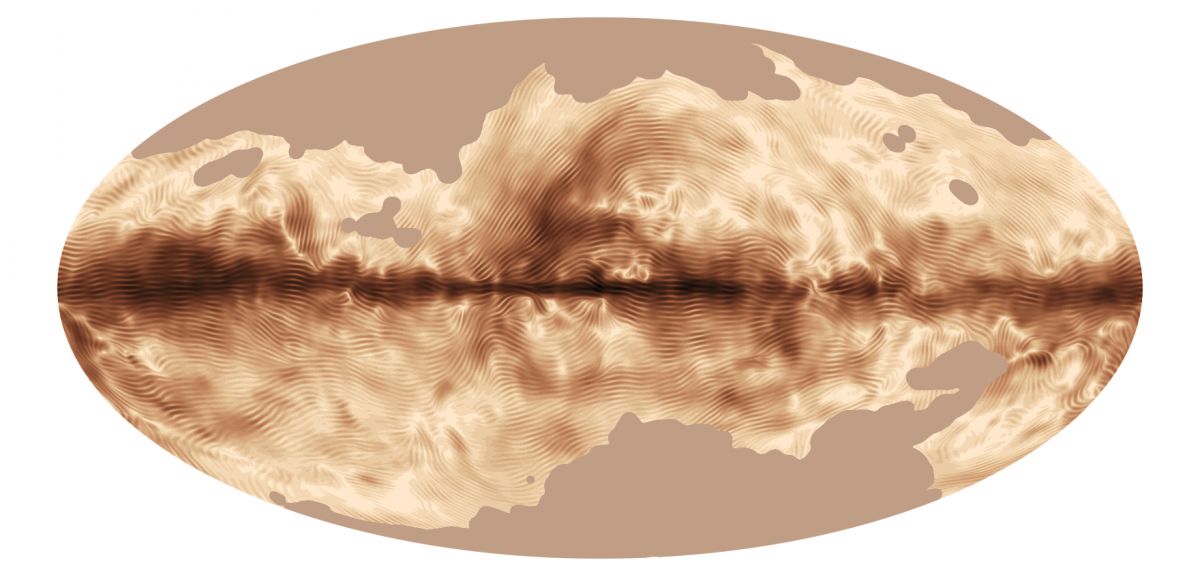

Data from ESA's Planck satellite promises to help us gaze back in time at what the Universe looked like just after the Big Bang.

But between this snapshot of 'ancient light' from the newborn Universe, preserved as an imprint in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), and us lies the foreground of our own Milky Way, which is full of gas and dust that also emits light.

So to test theories about the rapid expansion (inflation) of our Universe, and maybe even spy the primordial gravitational waves - ripples in space time - that should accompany it, we first have to chart our own dusty neighbourhood.

A new map using data from Planck, produced by a collaboration including Oxford scientists, is helping us to do just that. As Joanna Dunkley from Oxford University's Department of Physics explains, it's revealing a lot about the magnetic personality of our galaxy…

OxSciBlog How can light tell us about magnetic fields?

Joanna Dunkley: We don't get to see the magnetic fields directly, but they do affect light that gets sent out by stuff that sits in the magnetic field. In our Galaxy that 'stuff' is mainly relativistic electrons and tiny dust grains.

For the electrons, they emit light while spiralling around magnetic fields. For elongated grains of dust, they prefer to line up with their long side at right-angles to any magnetic field. They are heated up by star-light, and release their heat as infrared light. This comes out preferentially along their long side. So the orientation, or polarisation, of the light, tells you how the dust grains are aligned, which in turn tells you what direction - and how strong - the magnetic field is.

OSB: Why is studying our galaxy’s magnetic field so hard?

JD: There are still huge questions about what our galaxy's magnetic field is. The problem is that we are sitting in our Galaxy, and have to try and construct a 3-dimensional view of the field, but we can only look from here on Earth. We can't get outside the Galaxy to look at the whole thing from different angles.

Parts of the magnetic field are neatly ordered, so in some directions we can see a long way through the Galaxy, but much of it is messy and tangled, and the information in the orientation of the light coming from the dust grains, or the electrons, gets very hard to interpret.

OSB: What does light data reveal about patterns in our galaxy's magnetic field?

JD: The orientation of vibration - or polarisation - of the light tells us what direction the magnetic field lies in. This new map from Planck measures the polarisation of light from dust grains and shows us that the magnetic field is aligned with the disk of the galaxy. It also shows that in some nearby clouds of dust and gas, the field is disorganised, with less ordered polarisation directions.

OSB: How could this data help in the hunt for gravitational waves?

JD: Gravitational waves from inflation also polarize light in the microwave to infrared wavelengths. That light comes from the Big Bang, but we have to separate out the Big Bang-light from the Galaxy-light. Happily the two signals vary differently with wavelength, so if you have maps of the sky at different wavelengths - which Planck does - you can better pull out the tiny signal from the Big Bang. This is something I work on at Oxford with my post-docs, and have developed statistical methods for separating the different signals.

OSB: What are the next big challenges for the Planck team?

JD: One challenge is to delve further into these polarization maps and help test whether the gravitational wave signal recently claimed by the BICEP2 team is really there. We are also currently finishing our second cosmological analysis of the Planck data - using the full set of data taken by the satellite - with results due out later this year.

Oxford academics had the chance to get on their soapbox today as part of the city's May Day celebrations.

Marchella Ward tells people 'Why Greek Plays Matter'.

Marchella Ward tells people 'Why Greek Plays Matter'.Organised by the Oxford Playhouse and Pegasus Theatre, 'Soapbox City' gave the people of Oxford the opportunity to address the Broad Street crowds on a topic of their choice.

The event came with the strapline '1 City, 1 Box, 12 Hours, 144 Voices' and included a 30-minute slot curated by The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Dr Oliver Cox, a Knowledge Exchange Fellow at TORCH, braved the heavy rain to speak on the subject of 'Heritage and Innovation: A Counter-Intuitive Partnership'.

He told Arts Blog: 'It was surprisingly nerve-racking, and it was strange hearing your own voice echo round Broad Street.

'But it was also really exciting to have a platform to say something about the University working together with the local community.

'My message today was "hug a tourist". Tourists are good for us and their money can help sustain and support us.'

Other speakers during an enjoyable and informative half-hour included Jonathan Courtney of the Faculty of Philosophy ('Altruism and Giving What We Can') and Marchella Ward of the Faculty of Classics ('Why Greek Plays Matter').

Also speaking in the TORCH slot were two physicists: Dr Francesca Day, who talked about physics and fan fiction, and Dr Grant Miller, who spoke on the subject of citizen science.

Completing the line-up was Dr Pegram Harrison of the Saïd Business School, whose topic was Antony Gormley's Exeter College statue.

Sixteen photographs by leading contemporary artists will be sold at a Sotheby's auction next month in support of the Bodleian Libraries' campaign to save the personal archive of William Henry Fox Talbot.

The campaign is a truly international effort, with the images being donated by major figures in contemporary photography from around the world, including Hiroshi Sugimoto, Miles Aldridge and John Swannell, Nadav Kander, Candida Höfer, Massimo Vitali, and Martin Parr.

Through this gesture, the artists are paying homage to Fox Talbot, the father of photography on paper and the art of which they are exponents.

For the auction, which will take place on 7 May, Sugimoto has donated two works, neither of which has previously been released into the market and both of which have been directly inspired by the Talbot archive. Also on sale will be Martin Parr's print taken at Lacock Abbey on the 150th anniversary of Talbot's invention in 1989.

Martin Parr's Lacock Abbey print will be one of the images on sale.

Martin Parr's Lacock Abbey print will be one of the images on sale.'We are enormously grateful to the contemporary photographers who have devoted their energy and talent in producing the works which are offered in this auction. We warmly encourage bids: acquire a great photograph and help save a major archive, all at the same time.'

The Bodleian's appeal was launched in December 2012 with an initial deadline of the end of February 2013 to raise the £2.2 million pounds needed for purchasing the archive.

A significant grant of £1.2 million from the National Heritage Memorial Fund gave the appeal a vital boost. And with the addition of a recent gift from the Art Fund of £200,000, along with donations from numerous other private individuals and charitable trusts, the Bodleian has managed to secure almost £1.9 million towards the purchase of the archive.

The Bodleian has successfully negotiated an extension to the fundraising deadline and must raise the remaining £375,000 needed to fully fund the acquisition by August 2014.

Private Thomas Highgate was just 17 when he became the first British soldier to be executed for desertion during the First World War.

Unable to cope with the horror and carnage of the Battle of Mons, he fled to northern France, where he was discovered hiding in a barn. He was tried, convicted and executed the following day.

Private Highgate was one of more than 300 soldiers executed by the British and Commonwealth military command during the course of the war.

Now, to mark the centenary of the conflict, award-winning photographer and Ruskin School of Art graduate Chloe Dewe Mathews will present a series of images focusing on the sites of these executions.

Titled Shot at Dawn, the project was commissioned by the Ruskin as part of 14-18 NOW, WW1 Centenary Art Commissions, the official cultural programme for the First World War centenary commemorations.

Chloe's series documents the locations at which British, French and Belgian troops were executed for cowardice and desertion during the First World War. Her photographs were taken as close as possible to the precise time the executions took place, which was usually at daybreak. Drawing on meticulous research, she has been able to locate the exact sites at which scores of soldiers found guilty of breaching military discipline were executed by firing squad.

Chloe told BBC Radio 4's Front Row programme: 'Part of what was so fascinating about the process was working with a real broad range of people – academics, local historians, people who have dedicated 20 years of their lives to researching these stories.

'So I collated all that information and research and then spent the next year and a half going on a number of visits to Flanders and France to find these locations. I stayed in hotels and got up very early in the morning, in the darkness, to make my way to these places, setting up my tripod and waiting for the dawn, for the light to rise. That was the moment when I'd take the photograph.'

Chloe, who described the commission as 'challenging', visited 23 sites in total, ranging from fields and slag heaps to former abattoirs.

Paul Bonaventura, senior research fellow in fine art studies at the Ruskin, said: 'Chloe's commitment and dedication to Shot at Dawn, which has been more than two years in the making, has been nothing short of remarkable. It is a privilege for the Ruskin School of Art to have collaborated with such a talented photographer on such a uniquely special undertaking.'

The photographs will be launched in book form at Flanders House in London on 14 July before embarking on a two-year international exhibition tour including Tate Modern, Stills: Scotland's Centre for Photography, and the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

- ‹ previous

- 171 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools