Features

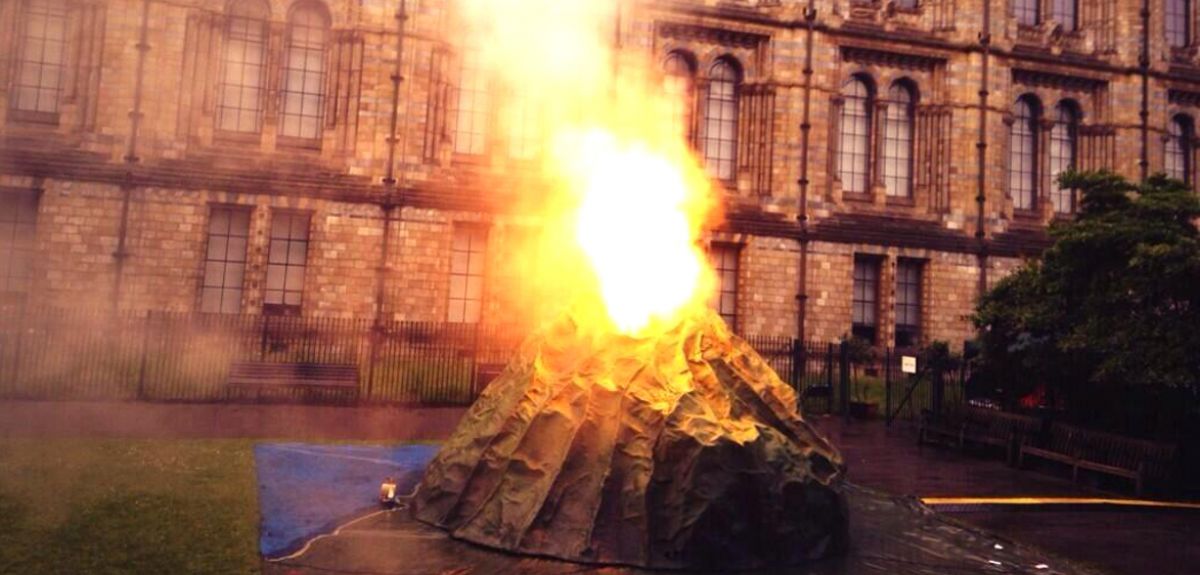

This week a volcano is erupting in central London: this three metre high model may not be as scary as the real thing but its mission is to highlight the real risks posed by volcanoes.

Located outside the capital's Natural History Museum, London Volcano is an exhibit dreamt up by researchers at University of East Anglia and Oxford University for Universities Week (9-15 June). So far the smoke and pyrotechnics have given just a taste of the eruption that struck the Caribbean island of St Vincent in 1902, but, on 11 June (6pm-10pm), this mini-volcano will recreate the Big Eruption in a free event open to the public.

I talked to David Pyle of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences, one of the scientists behind the exhibit, about the St Vincent eruption, the research the model draws on, and the serious side to blowing things up…

OxSciBlog: Why recreate the Soufrière St Vincent volcano?

David Pyle: St Vincent's volcano has erupted several times in the past 300 years; and each of these events has left us a record of what happened before, during and after the eruption. By looking at the written history of what happened, and analysing the rocks and other materials thrown out during these eruptions, we can better understand how to prepare for the effects of future eruptions.

We have chosen to recreate the 1902 eruption of St Vincent over the five days of the exhibit. This eruption was very damaging, but also recorded in great detail - both in terms of the physical impacts (the ash, mudflows and hot pyroclastic currents), and the wider social and economic impacts, and the ways that the island recovered from the eruption.

We are currently involved in a large international collaboration, called STREVA, whose focus is to reduce the negative impacts of volcanic activity on people and communities who live around volcanoes; and the approach this project is taking is to start off by seeing what lessons we can learn from the events of the past.

OSB: How can studying this volcano tell us about volcanoes in general?

DP: St Vincent's behaviour is fairly typical, both in terms of the nature of the eruptions, their size and spacing in time; and in the way that some eruptions are explosive, and others are not. So this means that it is a good 'physical' model for other volcanic systems, and we will be able to extend our new understanding from St Vincent to other volcanoes.

OSB: What were the biggest challenges in creating the model?

DP: Time! The opportunity to do this arose only a few months ago, but was not to be missed. And space - we weren't quite sure how big the model would need to be to have an impact. As it is, we are very happy with the result, even though it needs quite a large lorry to move it!

OSB: What do you hope people take away from the exhibit?

DP: We are really keen to engage with visitors to think about 'risks', and how to help to reduce the impacts of volcanic activity on communities whose livelihoods are tied to the volcano. The visual spectacle will make an impact, but beyond that we also want to show how we can use a huge variety of information sources to help improve our capacity to live with risks.

We are also using the event to link back to communities on St Vincent; listening to their stories of what happened in the last eruption on the island - in 1979; and working with the volcano monitoring and emergency management agencies in the Eastern Caribbean to develop and evolve mitigation plans for the future. This volcano exhibit is going to be the starting point for discussions with governments, agencies and businesses to help develop better plans for coping with future volcanic emergencies in the Caribbean and elsewhere.

OSB: What other volcanoes might you like to recreate and why?

DP: It is now more a case of 'we have a model, and will travel..' and my ambition is to reuse the volcano model as the focal point of an exhibit that we can take to schools, science festivals and exhibitions, to continue the conversation.

Our oceans aren’t just pretty to look at, they are doing a vital job storing away millions of tonnes in carbon emissions and mitigating climate change.

That’s the headline from a new report published by the Global Ocean Commission, co-authored by Alex Rogers of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology and Somerville College. I asked Alex how the report’s authors assessed the many ways we benefit from ocean ecosystems – benefits known collectively as ‘ecosystem services’ – and what more we can do to preserve them…

OxSciBlog: How do the oceans help to store our carbon emissions?

Alex Rogers: The oceans have taken up about 25-30% of all human carbon emissions and about 50% of those from the burning of fossil fuels. There are several routes by which this carbon enters the ocean. The primary one is the ‘solubility’ carbon pump by which CO2 dissolves into the ocean and is transported via ocean circulation into the deep sea. There is also the biological carbon pump whereby phytoplankton, microscopic organisms that use photosynthesis to fix carbon and convert it to tissue, take up CO2.

These microscopic organisms form the basis of the food chains of most of the ocean. As they die and sink into the deep sea or are eaten and their carbon is transported into deep water through the movement of animals or the sinking of their faecal material the carbon is transported downwards.

A small proportion of the surface derived carbon is stored in the deep sea. In our report we only looked at the biological carbon pump to look at how much CO2 is potentially sequestered through the actions of living organisms. This only represents a fraction of the CO2 sequestered in the oceans (total amount is estimated to be ~2.5 billion tonnes of carbon).

OSB: What impact could mining and other high seas industry have on their ability to store carbon?

AR: One of the fascinating things we found in our research was the evidence for the intimate connection of the activities of living organisms to nutrient cycling in the oceans. Fish, whales, gelatinous zooplankton all carry out a multitude of functions in ecosystems from feeding on other organisms and controlling their abundance to influencing the concentration of nutrients, such as iron, in surface waters and even stirring the oceans through their vertical and horizontal movements. When parts of the ecosystem are damaged by, for example, overfishing, then some of these functions are degraded with knock on effects to the rest of the ecosystem.

OSB: Why is it so hard to put a value on high-seas ecosystem services?

AR: We identified about 15 types of ecosystem service provided by the high seas but could only put a monetary value on a few of them. These services, which benefit humankind, range from the provision of food (i.e. fish) to the regulation of atmospheric gases (such as CO2).

Many of them cannot be quantified at present. This is for a variety of reasons but the main one was simply insufficient scientific knowledge of how the ocean works and the complex relationships between its biological and physical (or biochemical) components. Another reason was that even where values could be identified we could not ascertain what share of a particular service was attributable to the high seas.

An example of this is fishing (or mining!) of precious corals, where a significant component of global catch comes from the high seas but because of poor documentation of catches we do not know how much. In other cases the high seas contribute to ecosystem services that are in fact derived in coastal waters, examples including many fish species which might feed for part of the time in the high seas but which are caught in coastal waters.

OSB: How will these findings feed into your future research?

AR: The study has made us much more aware of the enormous knowledge gaps in terms of how the ocean works. For example, although our examination of carbon sequestration could estimate the rate of sinking of phytoplankton into the deep ocean there was little knowledge of active transport of carbon into the deep sea. This is where large numbers of organisms feed in surface waters, especially at night, and then dive into the deeps by day to avoid predators. These animals transport carbon into the deep sea but we do not even know how many there are, even, in some cases to orders of magnitude. Our research on deep-sea ecosystems will focus more on these questions in the future.

OSB: What could governments do to save high-seas ecosystems?

AR: Clearly there are problems with the management of human activities on the high seas. Overfishing and illegal fishing are two serious issues in a world of increasing human population and a resultant increasing need for fish protein.

At present governance of the high seas is very fragmented. Management of different industrial sectors is undertaken by different bodies, some of which are ineffective and do little more than divide up the proceeds from extracting ocean resources. These organisations often operate in isolation of international agreements on the protection and sustainable use of the environment.

Clearly a more joined up approach to ocean governance is required with increased transparency of decision making and assessment of institutional effectiveness. Where these organisations are failing, this must be identified and corrected. Policing the oceans must also be improved and we now have the technology to monitor much more closely what various parties are doing on the oceans. Some of these measures can be incredibly simple and cost effective. For example, insisting that all fishing vessels on the high seas, like other shipping, must carry an internationally registered identification number would help us identify those not following regulations.

Oxford social geographer Dr Jane Dyson took filmmaker Ross Harrison to a village 2500m high in the Indian Himalayans to chart some of the significant social changes taking place. The result is a 15-minute film titled Lifelines [scroll to bottom to watch] about the hopes and frustrations of the villagers in the state of Uttarakhand.

It is a place of great beauty, known as Land of the Gods because it lies in the shadow of the towering Himalayan peaks where some of the great Hindu deities originate. However, it is also one of India's poorest states, with low levels of urbanisation and a mainly agricultural economy. The village sits high on a ridge in Chamoli District, not far from the border with Tibet. Life under the towering peaks of Nanda Devi (7816m) and Trishul (7120m) is one of hard agricultural labour. Villagers move seasonally between three settlements at different altitudes, ranging from 2200m to 2800m.

Since Jane's first visit in 2003, life has changed. Then, it took half a day to trek to, and there was no power or telecommunications. Only the first five years of primary education were provided for in the village. By 2012, the village had a telecommunications tower, irregular electricity and a road (of sorts), while many people used mobile phones. It is now relatively straightforward for young people to obtain education up to high school level.

The film focuses on Makar Singh, a father with three young children who is completing a master’s degree by correspondence. He, like many of the youth, finds ways to channel his frustration with the lack of opportunity.

In the film, he explains: 'We have very few earning sources here. There are no companies, no factories. If the government creates a post, it will be for three or four people, but more than 1,000 of us apply. Everywhere there is competition. The competition is so high. Even if you're qualified you won't get selected. You could open a small shop but nothing more because there isn't the market. There aren't enough jobs for everyone, so there’s lots of unemployment.'

But it is also a film about hope. Following community protests, the government built a road and provided electricity and a school for the village, so levels of literacy have risen to almost 100% for people aged below 40. Ten years ago, the literacy level was nearer 20%. Makar Singh hopes these changes will provide a brighter future for the next generation.

Jane has worked in the village for over a decade. Her doctoral research in the village focused on children’s work and is published by Cambridge University Press in her book Working Childhoods: Youth, Agency and the Environment in India.

The work was conducted from the School of Geography and the Environment with funding from the UK Economic and Social Research Council.

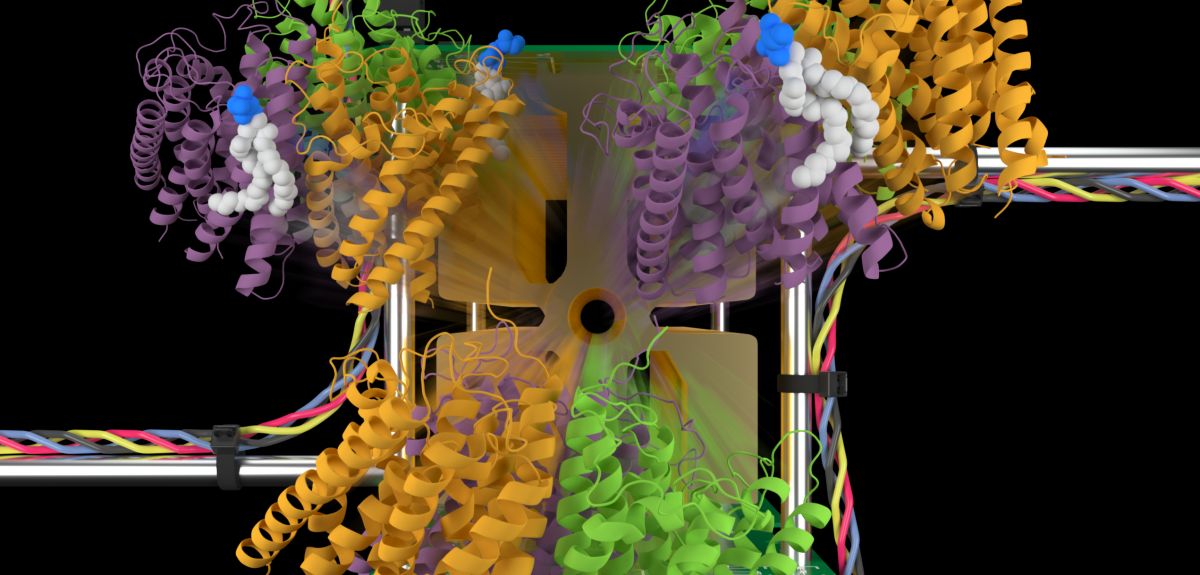

Protein machineries embedded in the membranes of our cells act as 'gatekeepers' controlling everything transported in and out of every cell in our bodies.

Because these machineries, called membrane embedded proteins, are vital to the way our bodies function they are the target of at least 40% of drugs. But one of the problems of targeting these proteins is that they are known to be influenced by lipids and current methods often struggle to distinguish between the effects of lipids and drugs.

Now Oxford University researchers report in Nature that they have found a way to assess what effect lipids have on proteins by measuring how lipids resist being 'unfolded'. By using a technique called ion mobility mass spectrometry, that propels proteins and their lipids into a vacuum, they discovered that by measuring resistance to unfolding they could rank these lipids based on their ability to stabilise membrane proteins.

'We could see lipids binding to membrane proteins but we couldn't work out how to rank their effects,' Carol Robinson of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry, who led the research, tells me. 'However, by measuring resistance to unfolding we were able to observe big differences between the lipids.

'We have found that they can change their overall stability - quite dramatically - and this can lead to structural changes and also has implications for the function of membrane proteins. They were much more intimately linked than we first thought - important for function and also for conformational change.'

She explains that the research was originally considered controversial since it was unclear how relevant measurements made using such techniques would be: 'We didn't know that the measurement of resistance to unfolding would correlate so well with function and stability. The unfolding is performed in the gas phase while function and stability take place in a biological membrane – it is surprising that there is such a good correlation.'

The new findings could have important implications in the search for new drugs:

'This approach is readily applied to drugs since the same methods of ranking lipids can be used to rank drug molecules,' Carol explains. 'We also think that we will learn a lot about the synergy between lipid and drug binding - something that is often very difficult to assess with current techniques.'

An Oxford University choir has been featured on Hong Kong television as part of its most recent tour.

The Oxford Gargoyles, a long-established jazz a cappella group, visited Hong Kong and Macau to perform at the first Meeting Minds: Oxford Asia Alumni Weekend, as well as the Cathay Pacific/HSBC Hong Kong Sevens rugby tournament and the Oxford University Society of Macau's fundraising concert in the historic Teatro Dom Pedro V.

The 14-strong choir's dazzling black-tie vocal jazz performances were a huge hit throughout the tour, as were the workshops it held at 10 local and international schools in the region. In total, the group put on more than 30 concerts at a wide range of venues, including Hong Kong City Hall, the Hong Kong Fringe Club, arts exhibitions, restaurants and shopping malls.

Media appearances included a performance at the Radio Television Hong Kong studio and a news item on the school workshops broadcast on TVB Pearl.

The Gargoyles have now returned to Oxford and are looking forward to performing at a host of college balls, garden parties and weddings this summer. Their end-of-term concert will be held at Magdalen College on Tuesday 10 June and will be raising money for the student-run mental health charity Student Minds. The choir will also be performing at the Edinburgh Fringe in August.

The Oxford Gargoyles would like to thank the Oxford University China Office, the Oxford University Society of Macau and the many Oxford alumni who supported the tour.

- ‹ previous

- 169 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools