Features

Despite being one of the most fast evolving sciences in many ways, gender equality is one area where the field of engineering is playing catch-up. But, in spite of this continued imbalance, little by little, female engineers are shaping the world around us with their research achievements, developing scientific solutions to real world challenges.

In celebration of International Women in Engineering Day (June 23) – an initiative intended to raise the profile of women in engineering and physical sciences and encourage other budding scientists to join them, we wanted to shine a light on a female academic engineering a difference at Oxford.

Dr. Dong Liu is an independent research fellow at Oxford’s Department of Materials and a Soapbox Science ambassador. Specialising in materials sciences, physical sciences and mechanical engineering, Dr Liu’s research is focused on better understanding of new materials for nuclear reactors and how this can drive further developments in nuclear energy production.

For those that are not familiar, what is Materials Science – and how does it differ from Engineering in general?

To make any effective device, structure or product, you need the right material(s). Materials Science is the study of all materials – from the things you use every day like plastics, glass and sports and health care equipment, to more industrial appliances in aircrafts, space shuttles and nuclear reactors.

I am interested in how materials react to extreme conditions, for example, inside a jet engine or a reactor core, where heat and irradiation is a problem. Understanding how and why the materials degrade and break is key to designing and making stronger materials. Compared with Engineering, Materials Science focuses more on the mechanisms of the material failure. By gaining this knowledge, we can understand their engineering behaviour better.

By understanding a material’s strengths and weaknesses we can optimise its use and eventually make our nuclear energy sources more efficient and effective.

Which material does your research focus on?

My primary research interest is on ceramic-like materials used in aero-engines, e.g. ceramic coatings on turbine blades protecting them from the heat of the engine, and a material called graphite used in the core of nuclear reactors at power plants in the UK and some other countries.

What is graphite?

Nuclear grade graphite is used as the core of all 14 operating reactors that provide about 20% of the total electricity in the UK. It is much purer than materials used day to day, such as lead in pencils, so it’s ideal for building the core of nuclear reactors - a lesser material would interfere with the reactions.

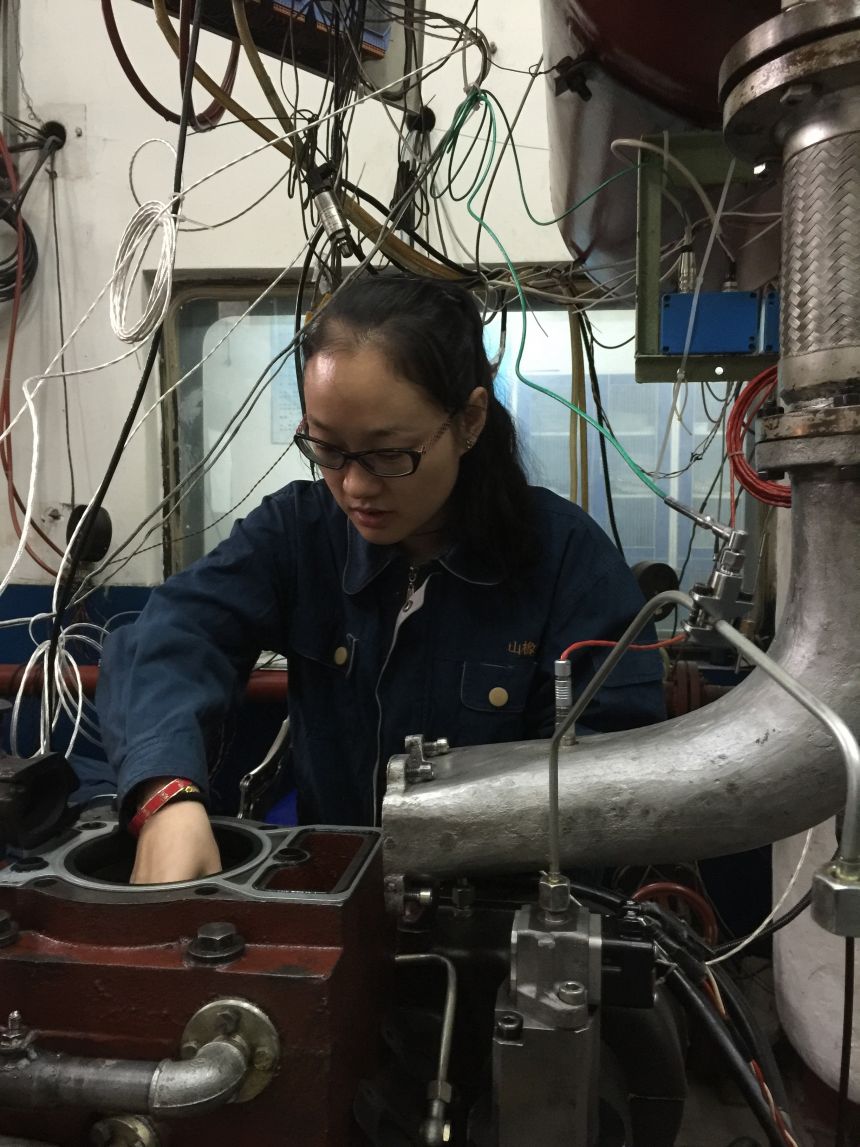

Dr Liu hard at work in the lab.

Dr Liu hard at work in the lab.What does your research involve?

Once installed, the graphite core cannot be taken out or replaced, so if it becomes unstable or develops cracks, we have to shut down the reactor. I study these cracks and work to understand why stability issues occur in general. By understanding a material’s strengths and weaknesses we can optimise its use and eventually make our nuclear energy sources more efficient and effective.

Working together with my colleagues at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, we heated our nuclear graphite to more than 1000°C to test the tolerance of the material. We found that the material actually becomes stronger in high temperature environments and was less likely to fracture when heated up.

What impact has this research achievement had on your career?

Publishing our paper in Advance Science has boosted my reputation in the nuclear graphite research community and allowed me more international research opportunities.

The material is used in nuclear reactors in many other countries, including Europe, USA and China, where they are working to build the next generation of reactors, which are more powerful and environmentally friendly than previous models. I am supporting this work, analysing different grades of graphite material so that we can understand and use their tolerance levels to create a superior nuclear reactor that enables clean energy.

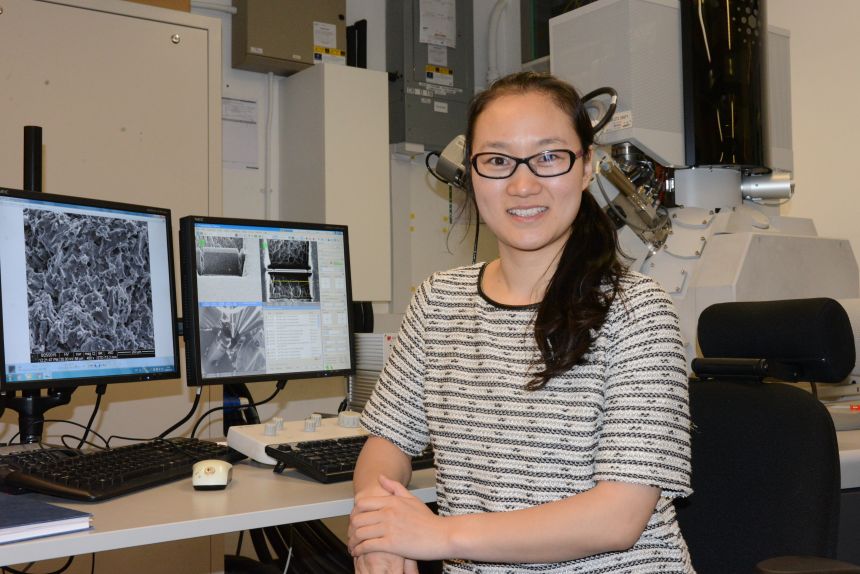

Dr. Dong Liu is an independent research fellow at Oxford’s Department of Materials, her research focuses on testing and better understanding materials used in nuclear reactor cores to make our energy sources more effective and sustainable.

Dr. Dong Liu is an independent research fellow at Oxford’s Department of Materials, her research focuses on testing and better understanding materials used in nuclear reactor cores to make our energy sources more effective and sustainable.How did you come to specialise in this area?

I am excited by research that has an industrial imperative, it makes me feel that I am solving a real problem that is related to everyday life and helps our society.

Some people assume that research is dull, but scientific engineering is all about getting your hands dirty. Taking things apart and blasting them with boiling hot X-rays is all in a day’s work for me, and I love it.

What drew you towards a career in science?

Education is very important in China and my parents played an important role in my passion for academia. Even at primary school my mum said to me; ‘you have to get a Doctorate degree when you are older’, so I have always had that goal.

I’ve always believed that a burning desire to learn is the most powerful driving force in life. When I look at where I am now, I know that I have made the right decisions.

What has surprised you most in your career?

I used to think that working in science would be lonely and I would be stuck in a lab on my own 24/7. But, communication is a big part of the job, and collaboration is key to overcoming challenges.

Some people assume that research is dull, but scientific engineering is all about getting your hands dirty. Taking things apart and blasting them with boiling hot X-rays is all in a day’s work for me, and I love it!

What advice would you give to anyone beginning or considering a career in academic science?

Be brave, take as many opportunities as you can and keep an open mind. Being a scientist is about more than publishing papers and experiments. You are part of a community that has a responsibility for influencing people’s science perceptions and understanding.

I am involved in the Nuclear Institute’s Woman in Nuclear (WiN) initiative and in organising Oxford Soapbox Science events - the national initiative to make science more accessible to the general public and raise the profile of female scientists.

Another tip is to be aware of independent research opportunities – such as funded research fellowships. I have had two while at Oxford: 1851 Royal Commission Research Fellow (Brunel) and another with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Fellowships have been key to my career, and helped me to grow as an independent young academic. You are the leader, the worker and the negotiator for your own research – effectively you ‘run the show.’ Applications can be competitive and time consuming, but the pay-off is worth it.

How has your experience as a women in engineering shaped your career?

For me, being a young woman in Engineering has shaped my career. It is great to be young, but in academia youth isn’t always a good thing. People often assume that you must be older to practice good science, or to have a senior position. Male or female, being or looking younger can lead to your work being challenged, so you need to really know your stuff and prove yourself

From a positive perspective being challenged only makes you get better at what you do. Before I came to Oxford as an independent researcher, if someone had asked me if I was ready for a permanent position I would have panicked. But, my experience has improved my confidence in my teaching.

Dr Liu is one of the core organisers for the Oxford branch of Soapbox Science - the national initiative to make science more accessible to the general public and raise the profile of female scientists.

Dr Liu is one of the core organisers for the Oxford branch of Soapbox Science - the national initiative to make science more accessible to the general public and raise the profile of female scientists.What do you think are the barriers to entry for women in STEM?

Stereotypes are a big issue. A student of mine once told me that her mother has a doctorate degree, but people always assume that the Doctor in her family must be her father.

Statistically less women are applying for jobs in science and engineering compared to men, which is why it’s so important to mentor young people to encourage them to take a science / engineering career.

I believe that everyone is equal and can make important contributions to science. A diverse workforce is needed to represent the multiple facets of knowledge, perspectives and values required to uncover the most significant findings.

How do you balance the stresses of work and home life?

Any work - science or otherwise, is like a marathon rather than a sprint. My philosophy is work hard play hard and I do lots of sports like kickboxing and hiking with friends in the sunshine.

What is next for you?

I am coming to the end of my Fellowships and will soon start a permanent Lectureship position with the School of Physics at Bristol University.

I feel really lucky to have been able to stay in academic science as long as I have and I feel it is my duty to raise awareness of women working in the sciences, sharing our cool research and letting others know that they can do this too.

What will you miss most about Oxford?

There is so much I will miss, but especially the people that I work with in the Materials Department - they are like extended family. I have lots of collaborative research coming up, so I will continue to be a visiting academic at Oxford.

I’ll miss the delicious, formal Mansfield College dinners, which are out of this world and great for networking - you never know who you are going to meet at the table. I recently met Professor Katherine Blundell who specialises in Astrophysics. She is so inspiring person and good at explaining complex science, she makes me think about how I can better communicate my own work.

View Dr Liu's paper 'Damage tolerance of nuclear graphite at elevated temperatures' here

A series of events continues this week that aims to generate dialogue around the issues facing refugees in the UK.

Initiated by Baroness Jan Royall, Principal of Oxford’s Somerville College, the series has engaged policymakers, academics, charities, students and members of the Oxford community with this important topic.

The series began with a panel discussion focusing on child refugees and access to education, and will continue tomorrow (Wednesday 20 June) with an event centred around women refugees. The event will feature not only a panel discussion but a special performance of a new composition by composer Sadie Harrison, set to a poem titled My Hazara People by Shukria Reazei, a young Afghan refugee and recent former pupil of Oxford Spires Academy secondary school.

It is the first product of a growing collaboration between the travelling, community-focused Orchestra of St John’s and the Oxford Spires poetry programme run by the poet Kate Clanchy.

The event is free and open to the public, and registration information can be found here.

Co-organiser Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey, a postdoctoral researcher in music at Somerville and Oxford’s Music Faculty, and associate conductor of the Orchestra of St John’s, said: ‘One of the aims of the Orchestra of St John’s “Displaced Voices” project is to amplify the voices of refugees by setting their words to music and creating opportunities for public performance. Setting a text to music does more than just create a venue for it to be heard: it adds a new dimension to the work – additional layers of meaning – by weaving in the perspectives of the composer and the performer.

‘Projects such as these that create and even magnify the constellations of cultural backgrounds and power relations between composer, poet, performers and audience members require conscientious navigation of the difficult space between collaboration and appropriation. Yet it is specifically these interstices that afford the possibilities for fruitful intercultural dialogue and warrant continued exploration.’

This week’s event will focus on the unique issues facing women refugees in this country. Chairing the panel discussion will be Baroness Royall, with contributions from Councillor Peymana Assad (Harrow Council), Fatou Ceesay (Refugee Resource, Oxford), Councillor Shaista Aziz (Oxford City Council), and Catherine Briddick (Law Faculty and Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford). A reception following the discussion and performance will feature food prepared by the women’s group at Refugee Resource, Oxford.

Catherine Briddick said: ‘Refugee women face legal and other barriers when they seek to access, receive and then benefit from international protection.

‘Asylum’s “proximity bias” – that it is only available to those who are able to leave their own state and enter one that provides protection – has meant that women have found it significantly harder than men to seek, never mind obtain, international protection. Less than one-third of protection-seekers in Europe, for example, are women, although this proportion is increasing.

‘When women do seek international protection they face ever more dangerous and illegal journeys, with women at particular and heightened risk of experiencing violence, including fatal violence.’

She added: ‘Once in the UK, women seeking protection must navigate a complex asylum system, often without having received appropriate advice and support. For example, a woman must explain why she fears persecution or harm in her country of origin but might not disclose an experience of gender-based violence if she is not given the proper opportunity to do so.

‘And the problems faced by refugee women do not end with recognition as a refugee or the granting of some other form of protection: issues and hardships include dependency on a husband’s asylum claim, separation from family members, and difficulty accessing language courses, as well as various types of prejudice.’

There will be one further panel discussion exploring the issues facing refugees held in the coming months, with the specific topic yet to be announced.

Wednesday’s panel discussion, reception and accompanying performance are supported by Somerville College, the Orchestra of St John’s and The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

An interdisciplinary seminar series considering the practices and politics of war commemoration over time has made its mark in Oxford this academic year.

The three-workshop series was organised by Dr Alice Kelly, a postdoctoral research fellow at Oxford’s Rothermere American Institute and Corpus Christi College, after she won a British Academy Rising Stars Engagement Award towards the project. Based on a course Dr Kelly initially devised for first-year undergraduates at Yale University, ‘Cultures and Commemorations of War’ has helped instigate an interdisciplinary dialogue about the history and nature of war commemoration across time, as well as its cultural, social, psychological and political aspects.

Dr Kelly said: ‘War scholars tend to work on just one war – for example, the First World War, the American Civil War or the Vietnam War. The aim of this series was to bring those academics – all working in different disciplines and at different stages, from early career researchers to advanced scholars – into conversation with one another, and into conversation with others outside the University working on war memory, including practitioners, policymakers, charities and representatives from the media and culture and heritage industries.’

The series, which featured four keynote lecturers, 27 speakers, and academic and public participants including veterans, was designed to have an intimate, thinktank-like atmosphere, where postgraduate students and early career researchers were able to play a major role. Dr Kelly said: ‘Being able to involve, train and champion postgraduate and early-career researchers has been one of the fundamental aims, and successes, of this series.’

Cultures and Commemorations of War workshop

Cultures and Commemorations of War workshopThe first workshop – ‘Why Remember? War and Memory Today’ – was held in November 2017 at the Rothermere American Institute and considered our current moment in war commemoration, drawing on the First World War centenary commemorations and the ongoing removal of confederate statues across the US. Keynote speaker was David Rieff, author of In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and its Ironies. Of the response from the audience, Dr Kelly said: ‘The conversation ranged from the complex politics of national remembrance to the commercialisation of 9/11 to the recovery of bodies of First World War soldiers at Fromelles. It was both academic and personal, scholarly and reflective.’

The second event, held in December 2017 at the Imperial War Museum and titled ‘Lest We Forget? Reconsidering First World War Memory’, focused on the case study of the Great War as a means of considering ‘live’ war commemoration. The event featured a keynote talk by the Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller, who devised the Somme centenary project We’re Here Because We’re Here, which took volunteers dressed as soldiers into railway stations, tube trains and other public spaces across the UK.

Dr Kelly, who has been on a Remarque Fellowship at New York University since January, came back early from the US to run the third event, held at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) in late May this year. This event – ‘Seeing War: War and Cultural Memory’ – featured a keynote talk by Professor Marita Sturken, author of Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero, which analysed the 9/11 and Flight 93 memorials. Closing with a contribution from a film historian, the day considered how different modes of seeing war shape cultural memory.

Dr Kelly added: ‘The way we remember war tells us about what our society values. The past few years have seen an explosion of commemorative activity at the local, national and international level, as well as calls to question our collective memory. Arguably there’s never been a more public culture of war memory, and memory wars, than this present historical moment. And this moment – for all of us interested in war memory – begs commentary, analysis and theorisation.’

All of the panels and keynote lectures have been podcasted and will be available soon on the website www.cultcommwar.com. The series is also on Twitter @cultcommwar. Dr Kelly is currently seeking funding to continue the series in the next academic year.

Next week, a conference hosted at Oxford will explore the latest research into ‘intact’ forests – large forested areas that remain mostly unharmed by human activity. Co-organiser Dr Alexandra Morel, a postdoctoral researcher in Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, explains why these threatened landscapes are so important to the future of the planet.

‘Forests are among the most ecologically important landscapes on Earth. Some 1.6 billion people depend on them, and 80% of animals and plants on land live in them. Preserving forests is one of the most cost-effective solutions to mitigating climate change and could help meet 30-50% of the Paris goal of keeping Earth’s temperature rise below 2°C by 2050.

‘In particular, “intact” forests – the large, unbroken swaths of forests whose ecological functions remain unharmed by human activity – provide extraordinary benefits for protecting wildlife, human health, water supplies and indigenous communities. Furthermore, intact forests play a significant role in the fight against climate change, the most pressing environmental threat facing our planet today.

‘Despite these extraordinary benefits, intact forests are disappearing. Since 2000, intact forests have diminished by over 9% – twice the rate of overall forest clearance. If destruction continues at this pace, half of today’s intact forests will be gone by 2100.

‘For the purposes of this conference, we are defining intact forests as forests that are free of significant human-generated degradation, including loss of wildlife. That doesn’t mean a forest must be free of all human presence to be considered intact, but ecosystem science is increasingly showing that forest function is impacted by “edge effects” – the changes that take place at the boundaries between landscapes – and over-hunting. Therefore, significant areas of contiguous forest with minimal human disturbance and a large core area behave differently from smaller areas of forest within a highly fragmented landscape.

‘As for why these landscapes are important, we are keen for this conference to highlight the latest science on this question – specifically with respect to intact forest areas in tropical, temperate and boreal, or northern, regions. Some of the key values that are derived from a forest’s intactness relate to its ability to store and sequester carbon, its resilience to fire, local to regional climate regulation, watershed protection, and the ability to protect local communities from animal-borne diseases.

‘Threats to forest landscapes are manifold, primarily because their protection has not been made an international priority due to the focus on the current hotspots of deforestation and forest degradation. The fact that intact forest areas remain that way is due to their not previously being under direct threat. However, like other forest areas, intact forests are suffering hunting pressure, selective logging, mining and clearance for commodity production, which has significantly reduced their total area since 2000.

‘A multi-pronged approach will be necessary to mitigate these threats. Our conference sessions have been organised around some large topics, such as attempting to maintain intactness in logged forests, the relevance of international policies and financial instruments in incentivising intactness, and the effectiveness of protected areas, including indigenous reserves, for maintaining intact forest area. The fundamental responsibility to protect these areas lies with national and sub-national governments – however, it is increasingly recognised that these actors need additional support, both technical and financial, to achieve adequate protection of intact forests.’

The ‘Intact Forests in the 21st Century’ conference will be held in Oxford from 18-20 June.

It's a question many people thought would be impossible to answer: what did ancient Greek music sound like? Too much time had passed, and the evidence necessary to recreate and experience the sounds that the ancient Greeks heard was thought not to exist.

Professor Armand D'Angour of Oxford's Faculty of Classics thought otherwise.

It has long been taught that Hebrew liturgical music underpinned the ninth-century Gregorian plainchant that lies at the root of the history of Western music. However, Professor D'Angour's groundbreaking research has now shown that elements of the West's musical idioms may be traced much further back in time, indicating that our music has a clear basis in much earlier European practices.

Although ancient Greek music has been investigated intensively since the 16th century, for 500 years it seemed impossible to get a sense of what it would have sounded like. Now, sounds not heard for 2,000 years can be experienced thanks to collaborative research in reconstructing the melodies, instruments and rhythms. Over the past five years, accurate replicas of ancient Greek instruments have been created and have been used in performing scored texts of ancient works surviving on papyrus and stone. Auloi (double pipes played using circular breathing techniques) have been reconstructed, including one from an original second-century instrument now on display in the Louvre. The kithara (a stringed instrument that was used as a large concert lyre) has been remodelled with reference to images found on ancient vases. The integration of these instruments into this research gives an authentic feel to the sounds that we hear.

The texts of ancient Greek poetry were intended to be sung or spoken along with music. The earliest music that may be speculatively recreated is that of Homer, who composed his epics around 700 BC to the accompaniment of a four-stringed lyre. The sound of epic song has been recreated (following work by the late Professor Martin West) using the four notes that would have been available to Homer, and improvised on the basis of the pitch inflections of ancient Greek (in which the syllables of words went up and down in pitch at specified places).

In other cases, fragments of the melody and rhythms have survived to give a more complete sense of the original piece. The most valuable of these is a papyrus fragment with the music from a tragedy, Euripides' Orestes, originally produced in 408 BC. Another source, a stone tablet from Delphi, shows the melodic notation of Athenaeus' Paean from 127 BC. Professor D'Angour has worked to fill in the gaps, and the performance of these pieces provides a thrilling insight into what the ancient Greeks would have heard.

So what's next? Currently, Professor D'Angour is working with around 30 further documents of ancient music to continue to recreate the works that were played and sung. The aspiration is to put on, for the first time since antiquity, an ancient tragedy accompanied by the kind of music that it would originally have been accompanied by, perhaps in one of the great theatres that survive from the ancient world.

- ‹ previous

- 71 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria