Features

'It became very hard to breathe…but I just had to remember to keep calm and still.'

You might be thinking that this sounds like a hapless victim from one of the increasingly ubiquitous Nordic noir dramas taking over our TV screens – so you may be surprised to learn that it's the experience of one of the subjects in a recent University of Oxford study! Olivia Faull and colleagues from the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (based in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences) devised an experiment to look at what is happening in the brain when we might be about to become breathless. And the results have striking ramifications that will help us better understand – and may eventually lead to new treatments for –asthma and other chronic respiratory disorders.

Asthma costs the NHS £1bn a year, and the economy a further £2bn, due to time off sick (Asthma UK). It has long been suspected that some cases of asthma may be made worse by stress and worry. Sometimes breathlessness is out of proportion with what is actually happening physiologically in the lungs. In some people anxiety or worry can even bring on an asthma attack. Researchers in Oxford became interested in what is happening where in the brain when this reaction occurs.

A normal functioning PAG is clearly a good thing. We need to know when we are in danger, whether from something we could run away from – such as a hungry lion – or something we can't escape but could endure, such as becoming breathless. But what happens when things go wrong?

Scientists have known for some time that a tiny part of the brain called the periaqueductal gray (or PAG for short) plays an important role in how we perceive threat. Animal studies have revealed this bundle of cells in the brainstem to be the interface between automatic processes – such as breathing and heartbeat – and consciousness. The PAG is a group of cells ('grey matter') less than 5mm in diameter. Historically it has been very difficult to study in humans because it is so small and buried so deep. But the Oxford team managed to isolate the PAG using state-of-the-art magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with super fine resolution.

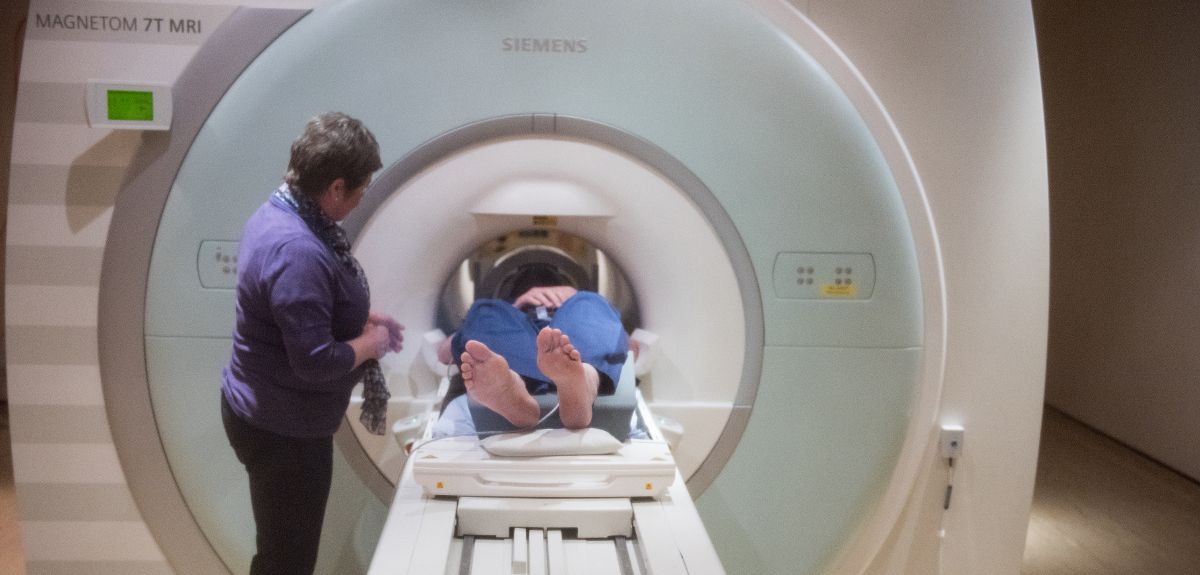

Olivia and colleagues scanned a group of healthy volunteers in the ultra high-field 7 Tesla MRI scanner. The volunteers wore a breathing system similar to a snorkel, that could be altered to produce a resistance when subjects breathed in (like breathing through a very narrow straw). During the scan, subjects looked at a screen that showed three different symbols at various times. Eventually the subjects learnt the meaning of the symbols – for instance the triangle meant that nothing would happen and they could breathe normally, and the star meant that their air would definitely be restricted and they would become breathless.

Volunteers therefore learned when they may be about to find it difficult to breathe. Olivia was then able to look at what was happening in the PAG both when people thought they might become breathless, as well as during the difficult breathing itself. Olivia wanted to know what was happening when people anticipate breathlessness, to better understand the stress and anxiety that exacerbate it. The study found that averaged over all participants, a particular subdivision of the PAG (called the ventrolateral column) became active when people anticipated that they might become breathless, and another subdivision (called the lateral column) became active while they were actually breathless. This means that different subdivisions of cells within the PAG are doing different things throughout the course of breathlessness.

A normal functioning PAG is clearly a good thing. We need to know when we are in danger, whether from something we could run away from – such as a hungry lion – or something we can't escape but could endure, such as becoming breathless. But what happens when things go wrong? It could be that in people who are hyper-sensitive to threats, the function of the PAG or its communications to the rest of the brain are altered. For example, some people with asthma may get very stressed if they can't find their inhaler, and this may even bring on an attack: perhaps the PAG is telling them that they are in danger of becoming breathless (even if, physiologically, at that moment they are breathing normally).

Now that this ground-breaking MRI experiment has enabled researchers to know where and how to look at the PAG, they can carry out further studies to find out more about asthma and other conditions where the physiology doesn’t match the perception – such as chronic pain or panic disorders. Such work could lead to the development of new treatments, to see whether they have any effect on this tiny, hitherto inaccessible part of the brain. These could be new medicines or new behavioural interventions such as as mindfulness or cognitive behavioural therapy, or combinations of both.

The full article is published in the journal eLife.

Today poetry fans around the world are celebrating World Poetry Day.

To mark the day, we asked poetry experts from our English Faculty and Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages about their own research into poetry, and what poems they recommend we should read today.

Later in the article, Professor Simon Palfrey of the English Faculty explains his collaborative scholarly and artistic project Demons Land: A Poem Come True.

Before that, Philip Bullock (Professor of Russian Literature and Music) and Alexandra Lloyd (Lecturer in German at St Edmund Hall and Magdalen College, University of Oxford) who lead the Oxford Song Network at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), give their take on World Poetry Day:

Arts Blog: What is the purpose and remit of the network?

PB: I think we say something on our website about the network – that it ‘explores the interaction of music and words in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century European song tradition’. But that’s incredibly complicated, as you might imagine. Trying to find a common language that brings together musicologists, linguists, historians and performers is one of the major challenges, and we’ve brought together a wide range of scholars from different fields in order to try to establish some common research questions and discuss how we each think about song (we’ve even pushed our period boundaries by talking to some classicists too).

We’ve also experimented with a number of different formats. We’ve had some more formal, conference-style events, often linked with the Oxford Lieder Festival, where people talk about their own research in depth. But we’ve also had smaller discussion groups in which we hear each other’s work in progress, and that’s a great opportunity to open things up for further discussion.

And this term, we’ve held a couple of workshops with current Oxford students and leading experts from outside the university – Helen Abbott from Sheffield, and Natasha Loges from the Royal College of Music – in order to explore the relationship, and sometimes even the tension, between poetry and music in song, to ask how we might translate song lyrics into English, and to explore what kind of knowledge and experience singers and pianists need to have in order to put across the meaning of a song to an audience that might not necessarily understand the language in which a song is sung.

A rather selfish reason for putting the network together was to get some feedback on a book I'm currently trying to write on Russian song, and I must say that I've always come away from every event buzzing with new ideas and angles to explore in my writing.

AB: What do you think of the way poetry is approached in schools and in the media? How would you change this?

PB: I think poetry can sometimes seem terribly formidable, and people think that studying it often involves learning lots about the complex meanings of words and all the hidden references and technical tricks that poets use to work their magic. That's all true, and it’s an important feature of how I teach poetry to my own students. But I sometimes think we forget the physical, embodied side of poetry – words that are spoken, or sung by a living, breathing human being.

We've rather lost the habit of memorising and reciting poetry (at least in the UK – Russians still do it with a passion), and with that, we’ve lost sight of poetry as a kind of performance, where sounds and sensations are as important in creating a relationship with the audience as the words on the page are. One of the exciting things about song is that it can bring poetry alive in the most intense way imaginable – we’re not just hearing a particular composer’s take on a poem, but a performer’s entire involvement with both the words and the music.

AL: I'd second what Philip writes about the embodied side of poetry. The expressiveness of sounds, and the feelings we encounter – emotional, but actually also physical – are part of the experience it’s easy to overlook sometimes. It's always a wonderful moment when students, for example, discover enjambment (the continuation of a sentence beyond the end of the line) – the breathlessness experienced by the reader roots the poetry in something beyond the intellectual.

Poems are not, and should not be taught as, collections of printed words on the page, any more than music is. For instance, listening to different composers’ settings of one poem can reveal so much about the original text by drawing attention to its different parts.

AB: What would you like people to take away from World Poetry Day?

PB: Thinking just about music for a moment, I’d like to suggest that song represents a wonderful form of imaginary travel. Listening to a Schubert setting of Goethe, a Glinka setting of Pushkin, or a Debussy setting of Baudelaire allows us to imagine not just very different historical periods, but totally new linguistic and cultural worlds.

As a linguist, I worry that not enough people study foreign languages, whether as part of the school and university curriculum, or simply for pleasure and enjoyment. But it’s not true that we live in a monolingual culture – we’re surrounded by other languages, some of them spoken by people who’ve moved here and brought their culture with them, and others that have been imported in the form of subtitled films, surtitled operas or bilingual programmes for song recitals.

My first encounter with German was falling in love with Schumann Lieder as a melancholy teenager, and I first began to learn Russian by deciphering the texts of the poems that Shostakovich set to music – they were very much the passport to my later life as a linguist and every bit as important as the fat novels I also love reading.

AL: I'd like to emphasise the idea that poetry is ubiquitous, particularly in music. When David Bowie died in January I watched the video of his final single ‘Lazarus’, released just a few days earlier. I was struck immediately by echoes of Heinrich Heine’s poem ‘Wie langsam kriechet sie dahin / Die Zeit, die schauderhafte Schnecke!’ (‘How slowly she creeps along, time, the loathsome snail’) from his cycle ‘Zum Lazarus'.

As with Bowie's character in the video, Heine spent the last eight years of his life bedridden, suffering from paralysis and confined to what he called his 'mattress grave'. These two verses about mortality - one from the mid-19th century, one from the early 21st - give us perhaps a sense of the connectedness of the human condition and the role of the arts and poetic expression in confronting that.

Would you like to suggest a poem for our readers to read today?

PB: I've recently discovered Japan, and although I can’t speak a word of the language, I’m really enjoying discovering its literature in translation. Basho’s frog haiku is terribly clever – and has been obsessively translated in an attempt to fathom its many secrets. It's also about sound, so ideal for someone like me, who’s interested in poetry’s musicality.

AL: I'm also part of the team that runs the Oxford German Network. Our national competition last year was on the theme of poetry and our website has a feature with lots of suggestions for reading.

For today, I'd suggest reading Lewis Carroll's poem 'Jabberwocky' - it's such a wonderful example of how 'nonsense' has meaning through sound and performance. There are also plenty of translations of it online - from the 'Jammerwoch' to 'Siaberwoci' to 'El Dragobán'...

Demons Land

Demons LandSimon Palfrey, Professor of English Literature at Oxford University, leads a collaborative scholarly and artistic project inspired by Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene, which Professor Palfrey describes as 'perhaps the single greatest poem of the English Renaissance'.

Arts Blog: Why is Fairie Queene significant?

SP: Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene is perhaps the single greatest poem of the English Renaissance. I see it as a hallucinogenic masterpiece, erotic, ravishing, strange, and frequently very savage. Inspired by militant Protestant zeal, the poem was written in Ireland during the 1580s and 1590s, when Spenser served the English crown during the most violent years of the Elizabethan conquest. It presents an unbuilt world, and asks on what principles we might create a virtuous person and a reformed society.

Spenser's mission in Ireland failed. His poem both reflects and tries to redeem this failure, offering a model of the necessary future as much as a diagnosis of the present. Hence the imaginative premise of our project: that subsequent global history, a repeating mission of conquest, education, and colonization, can be understood as a tale of this poem coming differently, imperfectly to life. It has long been understood that the *Faerie Queene*, in its claim to change or to model lives, is an exemplary Christian humanist poem. In our project, FQ becomes the text of unfinished modernity.

Tell us about Demons Land?

Demons Land: A Poem Come True is a collaborative scholarly and artistic project telling the story of an island in which Spenser's poem comes beautifully and terribly to life. This is the project of the Collector, a Romantic who around 1800 vowed to remake an island at the bottom of the world into a poetic utopia. Demons Land becomes a shadow history of Britain's most notorious colony, the prison island called Van Diemens Land.

Like Spenser's mission in Ireland, the Collector's dream failed: not because his world failed to be like the poem; but because both the poem and the land were other than he thought. They had indigenous energies, lives, untapped implications that his discipline hadn't imagined.

The questions we ask are very basic. We are all familiar with the idea that a poem might reflect or record history. But what if it predicts history? What if history is itself structured like a poem? And we can extend these questions to life itself: what if lives happen as they do in poems, where they only have existence if they are seen, or only matter if they are sympathized with?

What if each individual life is not a self-sufficient experience, but an allegory of something other? What if metaphors are true, or life is organized in rhymes, stanzas, endlessly repeating rhythms? The question becomes: what does it mean (for society, or history, or a life) for a poem to come true?

Questions such as these cannot really be tested in conventional scholarly forms. They need a correspondent creative experiment. So the Demons Land project explores how different crafts and disciplines - poetry, painting, film, music, masks, puppetry, and creative literary criticism - can combine to embody a poetic vision. All of this will come together in an exhibition/installation telling the history of the experiment.

How do their imagined worlds differ?

Demons land is at once a repetition, an interpretation, a subversion, and a radical modernisation of Spenser's poem. *The Faerie Queene* is notoriously unfinished. Demons Land continues the story, and purports to complete the poem, by means of a simple premise: that FQ is the prophetic text of western modernity, coming imperfectly, differentially true throughout the dominions conquered or settled by the English.

Demons Land is the epitome of this history, being the suppressed pre-history of Van Diemens Land, which itself echoes the earlier histories of Ireland and America. History is thus structured recursively, like a poem: Demons Land repeats itself to this day.

Hence the fictional postulate of our project: that a contemporary woman discovers a store of texts and paintings deriving from Demons Land, and undertakes to recover and publicize this unknown history. But then she repeats the story in less predicted ways as well - like the Collector, she begins to be possessed by it, and to identify in personal and even perverse ways with the figures in FQ/Demons land.

What will the product of your research project be, and when/where can we see it?

The main products will be the exhibition, its films and paintings, and a book I am writing telling the history of Demons land. As well as an online version of the exhibition, we will exhibit in locations whose own history speaks to our project, adapting our narrative to each host. The first showing will be in the gardens and temples of Stowe National Trust, designed in the early eighteenth century as an architecturalised Faerie Queene - like Demons Land, a place made in the image of the poem, as an act of political critique and fantastic idealism.

The second showings will be in Scotland, in the Gothic Mount Stuart house on Bute - another monument of beleagured idealism, and an island whose semi-disappeared history mirrors that of Demons Land - and in Glasgow, the great port of empire.

What would you like people to take away from World Poetry Day?

That poetry speaks directly to the possibilities - beautiful and terrifying - of life and history; that good poetry is always unfinished, awaiting and adapting to new readers.

Professor Marcus du Sautoy.

Professor Marcus du Sautoy.For the mathematical community it was the announcement in 1993 that Andrew Wiles had finally proved Fermat's Last Theorem. I was in the library at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem on my post-doc year trying to crack the problem I was currently obsessed with when a fellow post-doc excitedly whispered the news in my ear. I can still remember the thrill and excitement of realizing that I was alive at the moment when the most iconic unsolved problem in mathematics had been cracked.

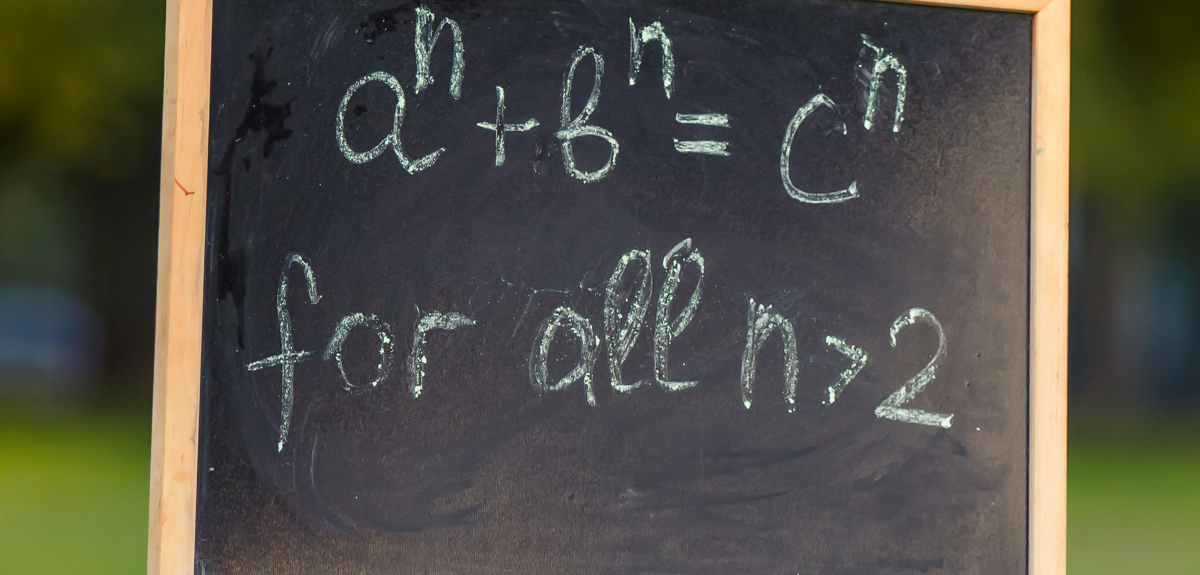

For 350 years we'd been trying to prove Fermat right and now finally we knew that those famous equations xn+yn=zn had no whole number solutions if n was bigger than 2. It is important to recognize that knowing this in itself did not change the landscape of mathematics. What was important was the journey that mathematicians had gone on from that moment, which all began with Fermat's marginal comment about having a proof too big for the margin (surely the biggest tease in mathematical history) to the final QED that Wiles had placed at the end of his proof.

As Wiles always acknowledges, there are many names that carried the baton of the proof from Fermat: Euler, Germain, Legendre, Kummer, Taniyama, Shimura, Weil, Frey, Ribet, Serre and many more. But every mathematician recognized that the seven-year marathon that Wiles ran to complete the proof was an extraordinary feat of mathematics. Before the announcement, no one believed we were anywhere near the finishing line.

But with the sense of excitement though came a slight hint of melancholy. Fermat's Last Theorem had been such a motivating enigma for many of us, there was a sense of sadness that the journey was over, like that moment when you finish a great novel. For the public there was even a belief that Fermat's Last Theorem really was the last theorem, and that we'd 'finished' maths. So it has been important to recognize that although Wiles' work was the completion of one journey, it actually opened up exciting new pathways for new journeys.

I asked Wiles shortly after he published his proof what great unsolved problem he would regard as worthy of replacing Fermat in the public imagination, a problem that would fire up the next Andrew Wiles. He opted for a challenge that has an ancient heritage but a very modern reformulation that is connected with the work he is currently engaged in. The ancient formulation is called the Congruent Number Problem: find a method for determining whether a whole number occurs as the area of a right angled triangle all of whose sides have lengths equal to a fraction.

After centuries of false proofs, Fermat himself proved that the number 1 cannot be the area of such a triangle. Some believe that Fermat thought mistakenly that he could generalize his argument to prove his Last Theorem and that this was what he referred to in the margin.

The Problem of Congruent Numbers is simple to state, and a school child can start playing around with ideas. Yet it relates to one of the deepest questions of arithmetic called the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture, a conjecture that Wiles has been working on for decades and which is one of the millennium problems for which the Clay Institute is offering a million-dollar prize for a solution.

A cryptic marginal tweet by the likes of Andrew Wiles about a proof too big for 140 characters, and perhaps it could find its way into the public imagination as the next great unsolved problem of number theory. Until then, with the award of the Abel Prize for 2016, we continue to celebrate the proof Wiles produced of the greatest enigma of the last three centuries: Fermat's Last Theorem.

Marcus du Sautoy is the Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science and Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford.

Death is not a laughing matter. But an ongoing study into coroners’ reports into accidental deaths in Tudor England has turned up some deaths which do sound like something out of a slapstick comedy routine.

Professor Steven Gunn of Oxford University's History Faculty and Merton College is leading Everyday Life and Fatal Hazard in 16th Century England, a research project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). He estimates that there are 9,000 accidental deaths to investigate in The National Archives in Kew.

Although the project has produced some entertaining stories, which have been well covered in the media and on this blog, it has also provided a valuable insight into the life and working practices of the time, and how these changed over the 16th century.

The project has found that fatal accidents were more likely to take place during the agricultural peak season, with cart crashes, dangerous harvesting techniques, horse tramplings and windmill manglings all major causes of deaths.

Interestingly, it seems real efforts were made to manage these risks with 'health and safety' procedures. When mowing hay at harvest time, men would minimise the risk of hacking each other with scythes by walking across the field in a staggered diagonal line.

Tree fellers directed the tree to fall down in a certain direction to avoid being crushed by the falling timber.

Handbooks warned about the danger of climbing trees to get rid of crows' nests, because so many people died by falling out of trees to gather fruit and nuts.

'Reading about how people died in Tudor times, you might think that people must have been daft to have died the way they did,' says Professor Gunn. 'Actually people did make an effort to work out the risks and minimise them, but these methods didn’t always work.'

Follow the project and its latest discoveries on the website. Professor Gunn gave a TORCH bite-size talk at the Ashmolean Museum's DEADFriday event last year. A video of the talk.

Oxford's Brain Awareness Week, 14 - 20 March, is a chance to find out more about the way our brain works and some of the more surprising effects its complex mechanisms. There’s even an opportunity to take part in psychological research. The week aims to help people find out more about the brain and about some of the many Oxford University research projects that study the structures, processes, and outcomes of our brain and the factors, treatments and behaviours that affect it.

If you can't make it to the events for any reason, you'll find some of our videos, podcasts and links below. If you can make it, we'll see you there!

The brain is always fascinating, sometimes confounding and occasionally downright strange. If you want to know your own mind better, these events are for you.

Nicholas Irving, co-ordinator of Oxford Neuroscience

The free events include:

Public talk: 'Our Perception of Pain', Professor Irene Tracey

Museum of Natural History, Oxford

Tuesday 15 March 2016, 19.00–20.30 (Booking required, tickets free)

Professor Irene Tracey addresses issues including: Can we really see someone’s pain? Is it true that you get the pain you expect? How do anaesthetics produce altered states of consciousness so you don’t feel pain?

If you can't make it...

See all Oxford podcasts from Irene Tracey.

In this series of videos from the Wellcome Trust, Professor Tracey talks about pain.

Interactive activities: Light, Sleep & Brain Rhythms

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Thursday 17 March 2016, 10.00–14.00

Learn more about how our brains are affected by light and dark, and what this means for our sleep.

If you can't make it...

Research in conversation: Professor Russell Foster

Public talk: 'Gastrophysics', Professor Charles Spence

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford

Thursday 17 March 2016, 19.00–20.30

Professor Charles Spence on the world of ‘multisensory dining’: how taste and soundscapes combine to shape our eating experience.

If you can't make it...

Interactive research: The Genetics of Being Social

Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford

Saturday 19 March 2016, 10.00–17.00 & Sunday 20 March 2016, 13.00–17.00

Why do some of us find it easier than others to understand and get along with people? Help researchers from Oxford University’s Department of Experimental Psychology test if it’s all in your genes. This drop-in event is for ages 18+.

Interactive activities: Brain Hunt

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Saturday 19 & Sunday 20 March 2016, 10.00–16.00

A packed programme of activities for all ages in various parts of the Museum. Find out about the physical, soulful, mechanical and creative brain!

Public talk: 'The Visual Brain - The House of Deceits of the Sight', Professor Christopher Kennard

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Saturday 19 March 2016, 12.00

Come and find out more from the Head of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, an expert in visual perception – what we see and what we think we do.

If you can't make it...

PODCAST: Chris Kennard on Art, Illusions and the Visual Brain.

Interactive activities: Brain Aware

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford

Sunday 20 March 2016, 12.00–17.00

An afternoon with Oxford researchers, suitable for age six and upwards.

- ‹ previous

- 129 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria