Features

We know that the universe is roughly 14 billion years old, and that someday it is likely to end – perhaps because of a Big Freeze, Big Rip or Big Crunch.

But what can we learn by considering our own place in the history of the universe? Why does life on Earth exist now, rather than at some point in the distant past or future?

A team of researchers including astrophysicists from the University of Oxford has set about trying to answer these questions – and their results raise the possibility that we Earthlings might be the first to arrive at the cosmic party.

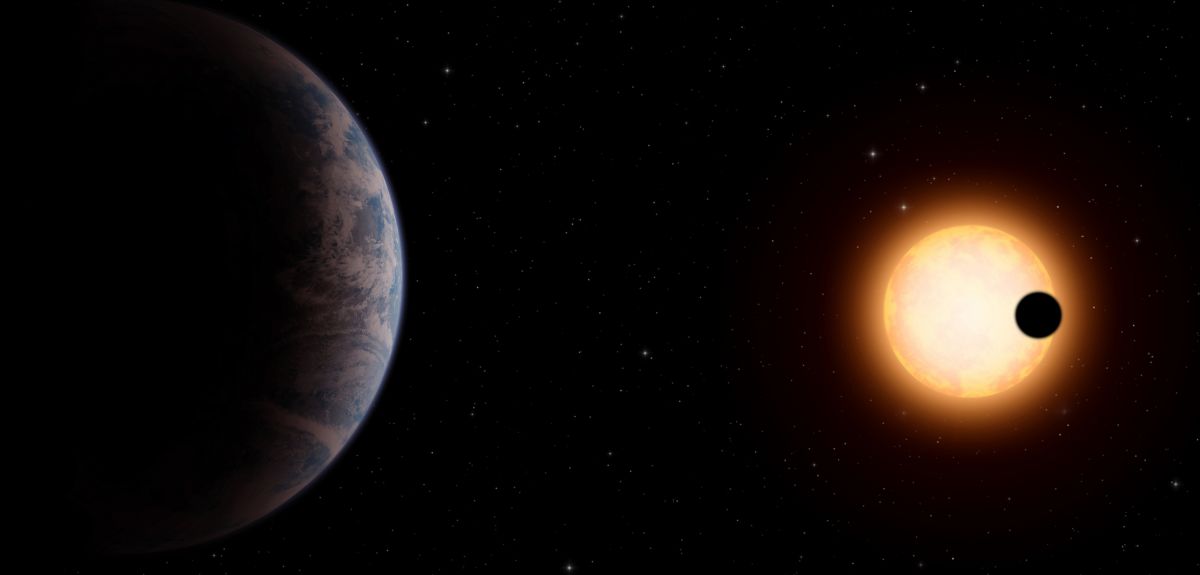

The paper, led by Professor Avi Loeb of Harvard University and published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, suggests that life in the universe is much more likely in the future than it is now. That's partly because the necessary elements for life, such as carbon and oxygen, took tens of millions of years to develop following the Big Bang, and partly because the lower-mass stars best suited to hosting life can glow for trillions of years, giving ample time for life to evolve in the future.

Dr Rafael Alves Batista of Oxford's Department of Physics, one of the study's authors, says: 'The main result of our research is that life seems to be more likely in the future than it is now. That doesn't necessarily mean we are currently alone, and it is important to note that our numbers are relative: one civilisation now and 1,000 in the future is equivalent to 1,000 now and 1,000,000 in the future.

'Given this knowledge, the question is therefore why we find ourselves living now rather than in the future. Our results depend on the lifetime of stars, which in turn depend on their mass – the larger the star, the shorter its lifespan.'

In order to arrive at the probability of finding a habitable planet, the team came up with a master equation involving the number of habitable planets around stars, the number of stars in the universe at a given time (including their lifespan and birth rate, and the typical mass of newly born stars.

Dr Batista adds: 'We folded in some extra information, such as the time it takes for life to evolve on a planet, and for that we can only use what we know about life on Earth. That limits the mass of stars that can host life, as high-mass stars don’t live long enough for that.

'So unless there are hazards associated with low-mass red dwarf stars that prevent life springing up around them – such as high levels of radiation – then a typical civilisation would likely find itself living at some point in the future. We may be too early.'

Co-author Dr David Sloan, also of Oxford's Department of Physics, adds: 'This is, to our knowledge, the first study that takes into account the long-term future of our universe – often, examinations of questions like this focus on why we arrived so late.

'Our next steps are towards refining our understanding of this topic. Now that we have knowledge of a wide catalogue of exoplanets, the issue of whether or not we are alone becomes ever more pressing.'

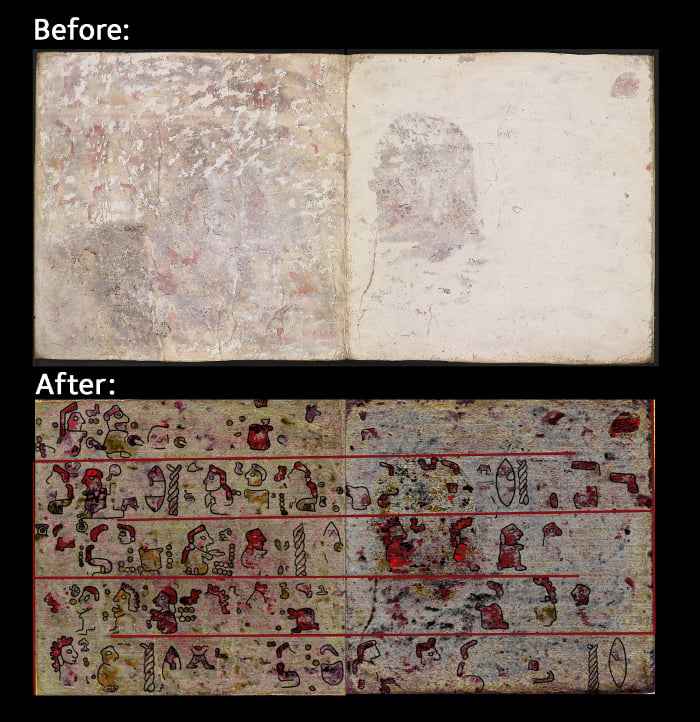

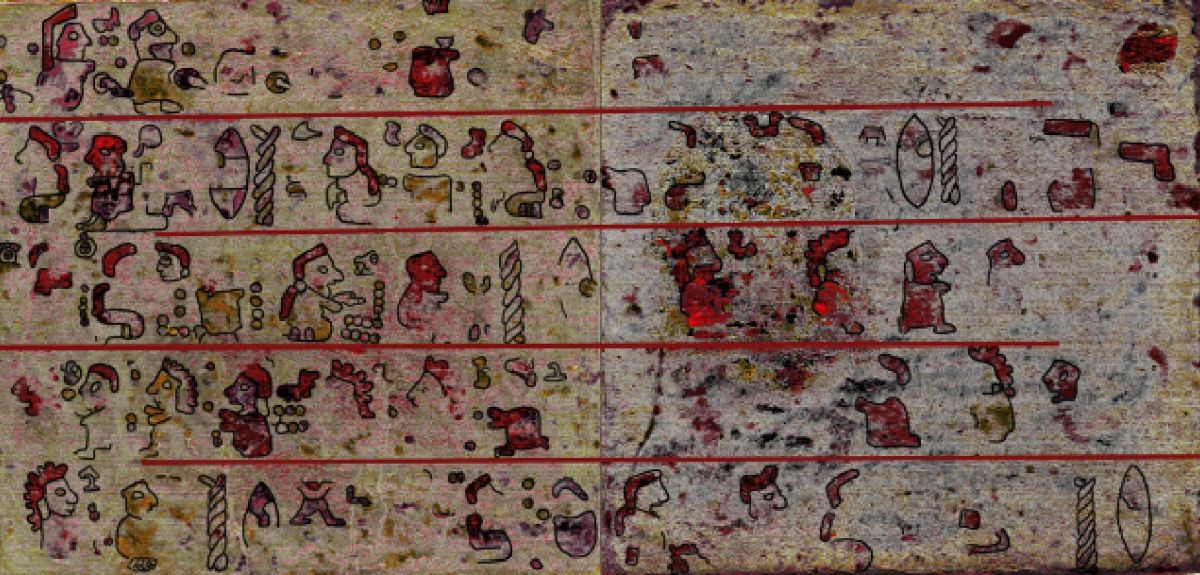

Researchers from the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries and from universities in the Netherlands have used high-tech imaging to uncover the details of a rare Mexican codex dating from before the colonization of the Americas.

The newly revealed codex, or book, has been hidden from view for almost 500 years, concealed beneath a layer of plaster and chalk on the back of a later manuscript known as the Codex Selden, which is housed at the Bodleian Libraries. Scientists have used hyperspectral imaging to reveal pictographic scenes from this remarkable document and have published their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Sciences: Reports.

Since the 1950s, scholars have suspected that Codex Selden is a palimpsest: an older document that has been covered up and reused to make the manuscript that is currently visible.

Until now, no other technique has been able to unveil the concealed narrative in a non-invasive way. The organic paints that were partly used to create the vibrant images on early Mexican codices do not absorb x-rays, which rules out x-ray analysis that is commonly used to study later works of art.

'After four or five years of trying different techniques, we’ve been able to reveal an abundance of images without damaging this extremely vulnerable item. We can confirm that Codex Selden is indeed a palimpsest,' said Ludo Snijders from Leiden University, who conducted the research with David Howell from the Bodleian Libraries and Tim Zaman from the University of Delft. This is the first time an early Mexican codex has been proven to be a palimpsest.

The findings have been widely covered in the world’s media this week.

Academics at Oxford University expect that the technology used to view the manuscript will enable them to make many significant discoveries in years to come. The hyperspectral imaging scanner was acquired in 2014 after the Bodleian Libraries and Faculty of Classics made a joint bid to the University’s Fell Fund.

Oxford classicist Dr Charles Crowther says the scanner will allow many different areas of the humanities to view details that have so far been “unattainable”.

'Oxford Humanities researchers have had extensive experience in the use of multispectral imaging over the last 15 years,’ he says. ‘Hyperspectral Imaging (HsI) is certainly the most exciting development in this field in that time.

'Its application to manuscripts in Oxford collections, whether carbonised Herculaneum papyri, parchment Achaemenid letters, or erased marginalia in the First Folio, has the potential to resolve details that previously have been unattainable and to bring to light significant new texts.'

What will the scanner reveal next? Arts Blog will keep you updated.

Britain's country houses boast some of the best-known gardens in the world.

It is less well-known that many of these were designed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, who was born 300 years ago this year.

Dr Oliver Cox, the University's first and recently-appointed Heritage Engagement Fellow, has co-curated an exhibition on 'Capability' Brown at the Bodleian Libraries' Weston Library, which is open until September 4.

In this video, he explains how Oxford is celebrating the anniversary, and what we should know about ‘Capability’ Brown, and how he got his nickname.

'Something I’ve found in my research is that Brown is really an entrepreneurial icon – he’s the James Dyson or Richard Branson of his day – because he creates a fantastic product that pretty much all of the aristocracy want to buy into, and where Brown is so successful is that he creates a brand around himself,' he says.

'He’s the man that will come and say, "your landscape, Sir, or Lord, or Lady, has great capabilities, and I can do something really spectacular with it".'

You're in hospital and you need to have a blood test: What do you think would reduce your pain?

- Sucrose (sugar water)

- Painkillers

You probably went with option 2. But in babies option 1 is often prescribed.

Ultimately, we would like to provide better pain relief for some of the most vulnerable patients in hospital.

Prof Rebeccah Slater, Department of Paediatrics

It is difficult to test whether painkillers work for very young children and we often don't know the best dose to give. But if Professor Rebeccah Slater and her research team at Oxford are successful we may find alternative ways to measure pain in babies and may eventually be able to offer babies some better options to soothe their pain.

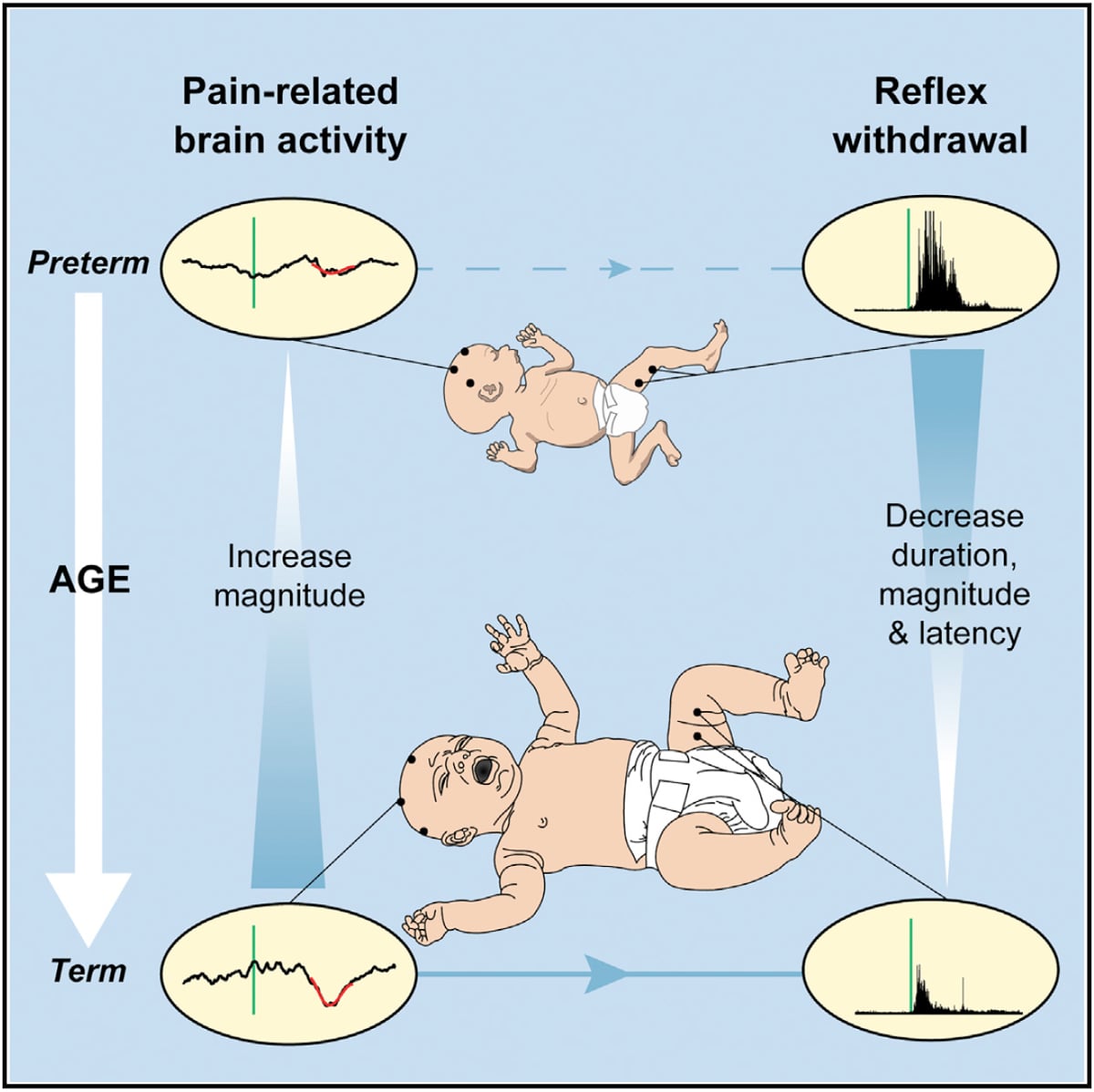

Their latest research, published in Current Biology and led by Caroline Hartley and Fiona Moultrie, looks at how babies who have been born early respond when a blood sample is taken from the heel of their foot.

Premature babies have to undergo various procedures, including regular blood tests. So, with the support of parents and working with the charity SSNAP, babies were recruited to the study and the team were able to measure both brain activity and reflex responses during this painful procedure.

Dr Hartley said: 'The youngest babies have disorganised and exaggerated motor responses when painful procedures are performed. For example, they might pull away both feet even when the blood test is performed on just one foot.

'As they get older, these reflex movements become quicker, shorter and smaller. They respond faster but don't pull away as much. However, you cannot directly infer how much pain a baby is experiencing from these responses – for example a premature baby can withdraw both their legs even in response to a light touch.

In the study the babies' brain activity was also measured by placing electrodes on their heads prior to the blood tests – this technique is called EEG (electroencephalography).

Dr Hartley said: 'The younger babies showed brain activity that was not specific to pain – a bright light or loud noise would cause much the same pattern of activity. As they got older, brain activity matured and the evoked brain activity increased.

'Considering both measures together, we found that older babies with more mature brain activity had more refined reflexes. '

This study suggests that top-down inhibitory mechanisms may begin to emerge during early infancy. As adults, we may instinctively stop ourselves from pulling our hand away from the handle of a hot pan if the alternative would be to tip boiling water everywhere, a potentially more dangerous result: that's an example of top down inhibition. The observation that, as the babies get older, more mature brain activity is related to more refined reflex activity, suggests that these inhibitory mechanisms may begin to play a role.

Pains, brains and clinical trials

Professor Slater explained the context of the research: 'Previous research in animals, which has been pioneered by colleagues at UCL, has shown that top-down inhibitory mechanisms develop in early life. Our results suggest that this research can be translated into humans.

'The results are also relevant to medical practice: doctors and nurses rely on behavioural observation to make judgements about pain in babies. Our results show that the movements of a premature baby in response to a painful procedure may not be proportionate to the amount of information that is being transmitted to the brain.

'That is also critical if we are trying to develop effective pain relief for babies. If we understand better how the immature brain processes information about pain, we may be able to use these patterns of brain activity to see whether different types of pain relief are effective in babies.'

Her next study, starting in September 2016 will test that. The team will measure brain activity and reflex withdrawal activity in a randomised controlled trial investigating whether morphine provides effective pain relief during clinically essential medical procedures.

Professor Slater said: 'Ultimately, we would like to provide better pain relief for some of the most vulnerable patients in hospital.'

We know a lot about JRR Tolkien's writings and his biography.

But what was the creator of Middle Earth like when he was being ordered around for a documentary?

An Oxford academic has found the answer while researching for a BBC Radio 4 documentary.

The documentary, which was broadcast on Saturday, follows the search by Dr Stuart Lee, an English academic and an expert on JRR Tolkien, to find an unbroadcast interview with Tolkien which was shot as part of a documentary on the Lord of the Rings author in 1968.

In the BBC archives, Dr Lee found 90 minutes of unbroadcast interview with Tolkien that was filmed in addition to the seven minutes used in the original documentary.

While making the programme, Dr Lee brought together the original documentary-maker Lesley Megahey, and three stars of the documentary: researcher Patrick O’Sullivan, Tolkien fan Michael Hebbert, and critic Valentine Cunningham.

Over a pint in Tolkien’s favourite pub, the Eagle and Child, Dr Stuart Lee explains what this video tells us about the author.

- ‹ previous

- 120 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria