Features

As a philosophical and practical concept, the idea of the division of labour – the separation of a work process into a number of tasks – can be traced back through figures as eminent as the economist Adam Smith and the engineer Charles Babbage (and even to a passage in Plato's Republic).

But while the division of labour is most commonly associated with mass production assembly lines, a new paper from researchers in Oxford University's Department of Zoology shows how bacteria can evolve a similar process in a matter of days.

Dr Wook Kim, first author of the study, published in Nature Communications, told Science Blog: 'Many sophisticated societies have the division of labour – not least our own, where it is central to much of our success both ecologically and industrially. Indeed, the term was used by the Scottish economist Adam Smith, who was a major player in the industrial revolution. Smith originally applied it to the idea of factory production lines, where different people specialise on individual tasks to manufacture something more complex. Smith wrote about manufacturing pins, but it is in car manufacturing that this process is perhaps best known and used.'

In biology, the division of labour is observed in a number of insect societies – including bees, ants, wasps and termites – in which workers specialise in tasks such as foraging for particular foods, nursing the young, or guarding the colony. This allows the colony to achieve things collectively that a lone individual could never do.

Dr Kim added: 'As well as insects, the division of labour is also known from a few species of bacteria that divide up their cells into specialised cells that do different things. There are a number of tasks divided up in this way, including toxin production, DNA uptake, and spore formation. However, in all cases, these systems have taken a long time – presumably millions of years – to evolve. By contrast, we have found that bacteria can evolve a division of labour in a matter of days. This opens up the possibility that the division of labour is much more widespread than we realised and is a way that many bacteria can deal with new challenges they face in the environment.'

Based on the knowledge that bacteria can evolve rapidly in response to environmental challenges, Dr Kim and colleagues, including senior author Professor Kevin Foster, turned their attention to the division of labour.

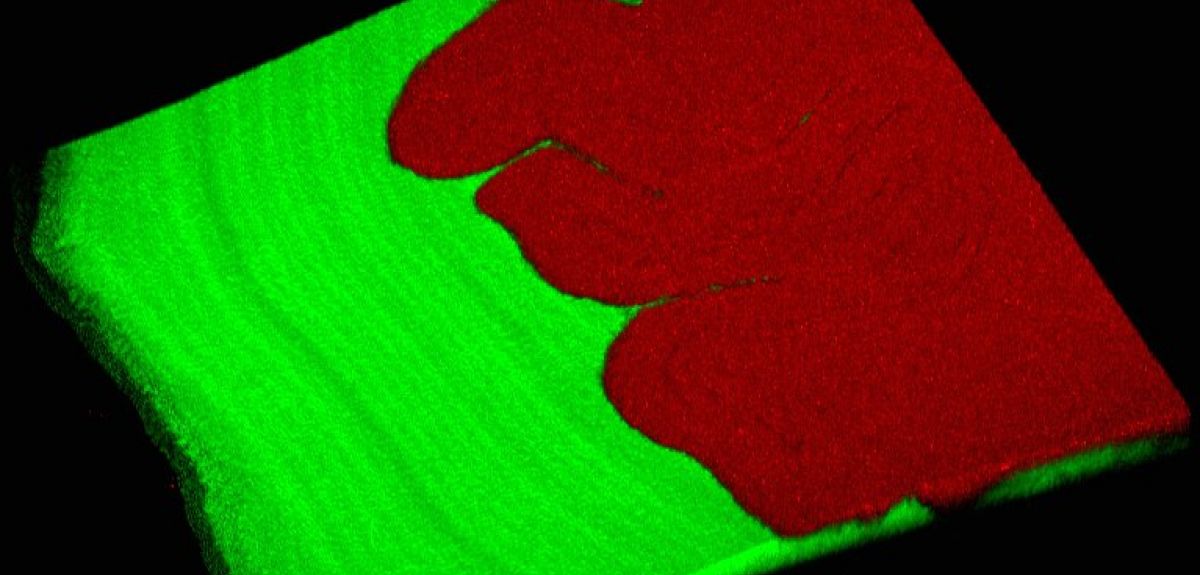

Dr Kim said: 'We observed that colonies of Pseudomonas fluorescens repeatedly evolved to spread out rapidly and gain new territory much more successfully than their ancestors. Moreover, we found that this territory-grabbing is done by the combination of two genotypes working together – a division of labour. One strain pushes from behind, and the other makes a wetting polymer that lubricates and allows them both to move outwards. So it's a really nice mechanical division of labour, where together they can do something that neither can do on their own. We also show that this all occurs with just a single mutation that makes the "pushy" strain more sticky and adhesive. This allows it to form a rigid mat behind the other strain and push it along.

'Given the propensity of bacteria to rapidly radiate – or evolve – in every environment, this process should effectively create many combinations and permutations of distinct genotypes that may lead to a division of labour. Our work is also testament of the power of evolution, through natural selection, to find elegant solutions to a problem. By simply putting the cells on agar, we inadvertently gave the bacteria the challenge of finding a better way to colonise the surface of the nutrient-rich agar. In the face of this challenge, they rapidly responded to generate this simple but elegant solution that relies on both teamwork and the division of labour.'

1 in 3 people born after 1960 in the UK will be diagnosed with some form of cancer in their lifetime, and each year, 4th February marks World Cancer Day, to raise awareness and encourage individuals and governments to fight the disease.

Oxford University has many research groups working at the cutting edge of the fight against cancer, and I spoke to one such researcher, Professor Colin Goding from the Ludwig Institute at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, about what cancer treatments might look like in the future.

We have something like 14 million million cells in our body, but only one in three of us, and over many years, gets cancer.

Professor Colin Goding

Oxford Science Blog: Why is cancer of interest to scientists?

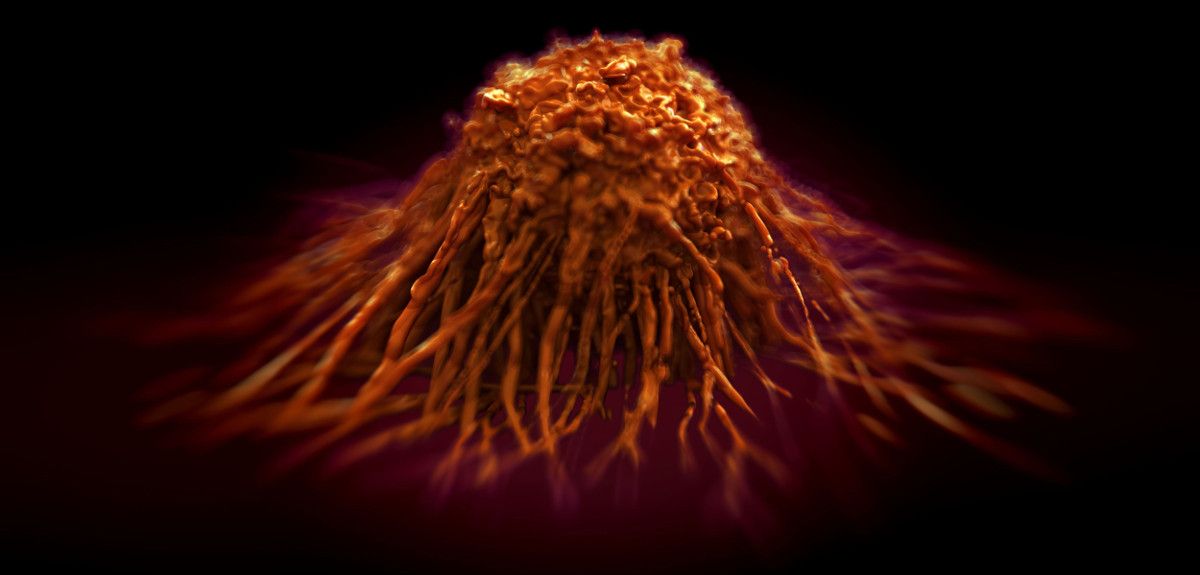

Colin Goding: We have something like 14 million million cells in our body, but only one in three of us, and over many years, gets cancer (defined by the uncontrolled division of cells which grow to form tumour). At the cellular level, cancer is extremely rare, and this is because we have mechanisms that block mutated cells progressing towards disease.

We study these mechanisms in melanomas, which are cancers that begin in melanocytes – the cells the produce the pigment melanin, which colours skin, hair and eyes. So melanomas are usually (but not always) skin cancers.

Melanoma are a good ‘model’ for cancer because we can see all stages of the disease: completely normal pigment cells, but also moles that have an activated cancer-causing gene that puts its foot on the ‘accelerator’ pushing cells to divide, counterbalanced by a very strong anti-cancer mechanism (present in all cells) that cuts the fuel to the engine so cells stop dividing.

We can also see melanomas that progress to spread across the surface of the skin, or those that start to invade and spread to other parts of the body. We’re particularly interested in how these state changes happen.

OSB: Given the rarity of the cellular events that lead to cancer, how does it ever take hold?

For 50 years, there was very little progress in treatments for melanoma.

Professor Colin Goding

CG: It is a complicated process, but to get a cancer, you need to inactivate the ‘brake’ that stops uncontrolled cell division, and there is more than one cellular braking system. On top of this, the genes encoding the ‘accelerator’ for cell division have to be turned on.

If these mutations occur in the wrong order, the engine stalls: there is no cancer. To get cancer, the mutations need to happen in the correct order: you lose the ‘brakes’, the cell machinery gets put in gear, and then the ‘accelerator’ mutations happen. Only then will the cancer progress.

OSB: Why are you particularly interested in melanomas?

CG: The advantage of studying melanomas is that, as a skin cancer, we can see all of these disease stages – in lung cancer, for example, by the time a patient comes in with symptoms, the cancer has usually already moved to quite a late stage.

There are now new drugs in the clinic that will help reactivate the immune system, enabling it to attack the cancer.

Professor Colin Goding

Another advantage of studying melanomas is that we understand a lot about the genetics of pigment cells, and many of the genes that have gone wrong in melanoma are the ones involved in the normal development of pigment cells. So we have a pretty good understanding of the genetic basis of this form of cancer: we know that the ‘accelerator’ genes are, for example, and we understand the braking mechanisms too.

Melanoma is also a form of cancer that affects many people: there are over 13,000 new cases of melanoma every year. The measure that correlates best with disease rates is childhood sunburn and cases of melanoma have been doubling every 10 years for the last 40 years. This is partially because there is about a 30 year lag between people becoming aware of the dangers of UV exposure from the sun and a change in disease rates.

And it is still the case that if you go to a park on a hot sunny day, or the beach, there are still people who are getting burnt. So there is still work to do in educating the public about the dangers of excessive sun exposure.

OSB: How has the treatment for melanoma changed over these decades?

CG: For 50 years, there was very little progress in treatments for melanoma: surgery to cut out early lesions before they started to spread is still a very effective therapy, but that was pretty much it.

But the realization that certain genes act as the accelerator pedal to push melanoma formation has led to drugs that target this mechanism. We now know which cancer gene responds to which particular drug. The response in patients whose cancer stems from these sorts of mutations is very good, but if the patient does not have the specific gene targeted by that drug, treatment with that drug might actually make things worse. So patients are now increasingly being tested for particular mutations before being treated with specific drugs.

The real problem, however, is that even if a drug works, for most patients, it is almost inevitable that resistance to that drug also appears some months later: the drug stops working, and the cancer carries on growing and spreading, eventually killing the patient.

A huge amount of work over the last 50 years or so has also gone into understanding the mechanisms cells use to block immune cells from infiltrating and attacking a developing tumour. Many of these mechanisms have now been identified, and the consequence is that there are now new drugs in the clinic that will help reactivate the immune system, enabling it to attack the cancer.

These drugs have also been very effective in many patients, but again, not all patients respond, there are many side-effects, and in some cases, resistance sets in after a while.

Essentially, resistance seems almost unavoidable for any one single kind of drug.

OSB: What can be done to combat this resistance?

CG: The first mechanism for cancer drug resistance is genetic: unless the disease is at a very early stage, within all the cancer cells in a patient’s body there is likely to be at least one that has another mutation that confers resistance to a particular drug or therapy. So when that drug is used, all of the other cells die, but the one with the mutation survives – and it then repopulates the tumour. This turns out to be quite a common mechanism for resistance to so-called targeted therapies that hit a key molecule.

The only way to really deal with this mechanism of resistance is to treat the patient early, and when the treatment is successful, to monitor the patient very carefully, with tools that are more sensitive that those we currently have, to track the cancer coming back.

This is because it’s a numbers game for genetic resistance - the chances of resistance developing are proportional to the number of cancer cells in the body. The greater the number of these cells, the greater the likelihood that some cells will be resistant to the drug being used. So even if you have a second drug that can kill cancer cells that survive the first drug, giving the second drug at a later stage, when there are many more cancer cells, means that it is again almost inevitable that a few cells will be resistant to the second drug too.

So treating as early as possible, when there are as few cancer cells in the body as possible, is the best way of overcoming genetic resistance.

OSB: How does your own work approach these treatment failures?

CG: We work on the second mechanism for cancer resistance, one based on the cancer cells in a tumour adopting different states.

We and others have found that in different circumstances, cancer cells can adopt different ‘personalities’ that can be more or less resistant to a particular treatment. The adoption of these different states is influenced by the microenvironment surrounding each cell, which includes factors like oxygen or nutrient levels, or signals from infiltrating immune cells.

All of these factors combine to induce the tumour cells to adopt different states. One of these states might be a drug-resistant state, another might be an invasive state, where cells start to move away from the primary tumour and spread throughout the body to form metastases.

For example, we now know, from the work that we’ve done on melanomas, that movement away from the primary tumour to seed these metastasis is primarily driven by the cancer cells’ microenvironment.

The interesting thing is that the cancer cell states are dynamic and reversible, and these micro-environmental influences can potentially be modulated by drugs. This isn’t quite the case for the genetic mutations, which are pretty much irreversible – you can target the altered protein made by the mutation, or you can try and kill the mutated cells when their numbers are low, but that’s the only way you can deal with the genetic issue in cancer.

But by understanding cancer cell states, we can perhaps turn a drug-resistant population of cells to a drug-sensitive one.

OSB: How could you bring about this change in state?

CG: We could do this by changing the micro-environment, or by finding drugs that drive cells to adopt a particular state. We’ve done this quite successfully for a drug called methotrexate – this was already in use for psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis, but we found out a couple of years ago that this drug switches on one of the genes that stops melanoma cells spreading to other parts of the body. Working in collaboration with another group, we also found that methotrexate also sensitized cancer cells to another drug, and so we’re currently working on ways to drive cancer cells into states responsive to different drugs.

We think many drugs designed for other diseases and not currently used to treat cancer might turn out to be useful for targeting some of these mechanisms which can switch cancer cells from one state to another.

OSB: How do you think cancer therapies need to change in the future?

CG: Cancer therapies need two things: first, we need to identify relapse (the cancer coming back) way ahead of when we do now, so that drugs that can bypass resistance to the first therapy can be given before resistance to the second therapy arises. This is similar to what we already do for bacterial infections: we don’t use the same antibiotic again when a first dose leaves resistant bacteria, and we ideally give a second antibiotic before the infection becomes re-established.

The second approach needs us to really understand the mechanisms by which cancer cells adopt inter-convertible states with different drug sensitivities. Then, we can use drug combinations, so that drug A sensitizes a tumour to drug B. We need to be really clever about how to do this and get the timing right. This requires quite a lot of work to understand fully the processes involved, but we’re getting there!

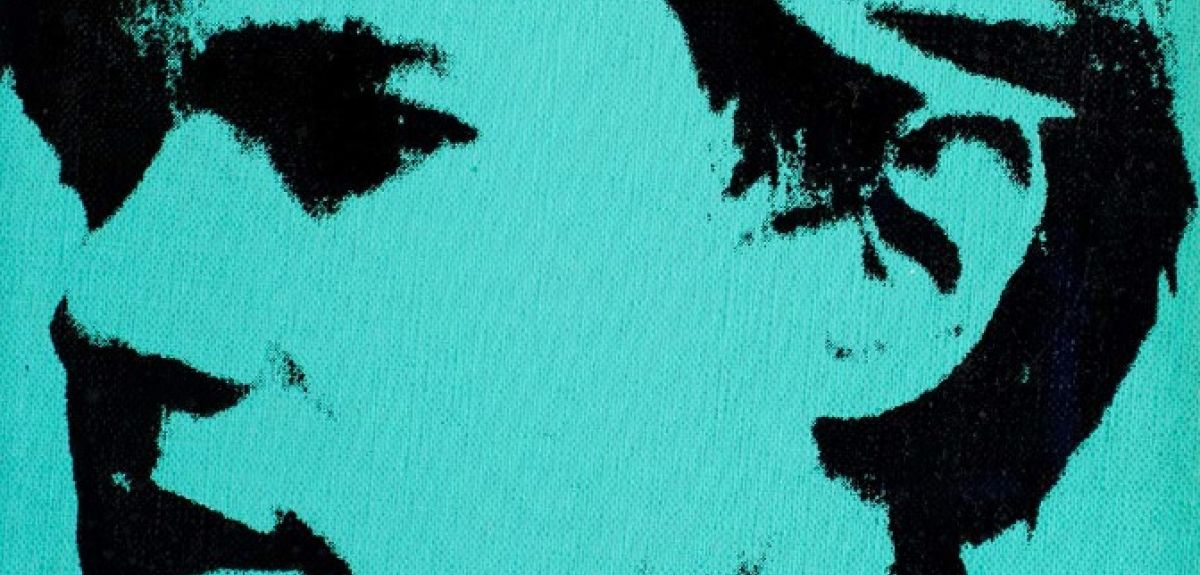

An exhibition of works by Andy Warhol has opened at the Ashmolean Museum.

The Museum has teamed up with the Hall Art Foundation in the USA, which has lent over 100 paintings, sculptures, screen prints and drawings from its private collection.

The Museum has also been loaned some the artist's films from The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

The exhibition opens today and runs until 15 May 2016.

Dr Alexander Sturgis, Director of the Ashmolean, says: 'We are hugely grateful to the Hall Art Foundation and to Andy and Christine Hall for making this exhibition possible with the generous loan of their superb collection.

'The substance and significance of Andy Warhol's art becomes more evident with each passing decade and this exhibition aims to add to what we know about Warhol by highlighting unfamiliar and surprising works from across his career.'

Sir Norman Rosenthal, The Hall Art Foundation Curator of Contemporary Art at the Ashmolean, says: 'Evermore, Warhol feels like the decisive artist of his generation who peered into the future and saw his world with all its glamour and with all its horror. The Hall's collection of Warhols demonstrates the artist's extraordinarily diverse output, as he reacts to his world with penetrating truthfulness and wit.'

Among the works featured are a series of screen prints of Joseph Beuys, based on a Polaroid photograph taken by Warhol in 1979 when the two giants of postwar art came face-to-face for the first time.

Curated by Sir Norman Rosenthal, the exhibition spans Warhol’s entire career, from iconic works of the '60s to the experimental creations of his last decade. It is arranged chronologically, opening with the early Pop masterpieces and portraits.

The first room includes works from key series such as Flowers and Brillo Soap Pads Box; a group of artists' portraits which features Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist and Frank Stella; as well as some of Warhol’s earliest experiments in screen print portraits with pictures of patrons, friends and celebrities (Troy, Patty Oldenburg, Ethel Scull, Jackie).

Films of the early ‘60s, including Sleep (1963) and Empire (1964) and a selection of Warhol’s Screen Tests, illustrate how the artist engaged with the moving image. This brings us to the point, in 1968, when Warhol was shot and seriously wounded by the feminist activist Valerie Solanas.

The main room of the exhibition is dominated by a spectacular display of Warhol’s commissioned portraits spanning the 1970s right up to the year before his death. The group features performers, socialites and politicians including the singer and songwriter, Paul Anka; American celebrities, Maria Shriver and Pia Zadora; the Princess of Iran; and the West German Chancellor, Willy Brandt.

The room also includes works (Hammer and Sickle, Mao, Dollar Sign, Crosses) that offer typically ambiguous and non-committal social and political commentary; and it features a sequence of pencil portraits from the 1980s based, like the prints and paintings, on photographs of figures such as Ingrid Bergman and Jane Fonda.

The gallery closes with Warhol's response to the challenge of abstraction with Rorschach, Shadows and Oxidation Paintings.

The exhibition's final room concentrates on the productive last years of Warhol’s life. In the Positive/Negative series, Warhol revisited the subject matter of his earliest Pop works - advertising, newspaper headlines and commercial packaging - and explored new territory in overtly political and religious works such as Map of the Eastern U.S.S.R. Missile Bases and Detail of the Last Supper. Another departure was Warhol’s use of simple slogans including Stress!, Art and one of his last works, the uncannily prescient Heaven and Hell are Just One Breath Away.

There are three weeks remaining to visit an exhibition of Armenian artefacts which have gone on display for the first time at the Weston Library.

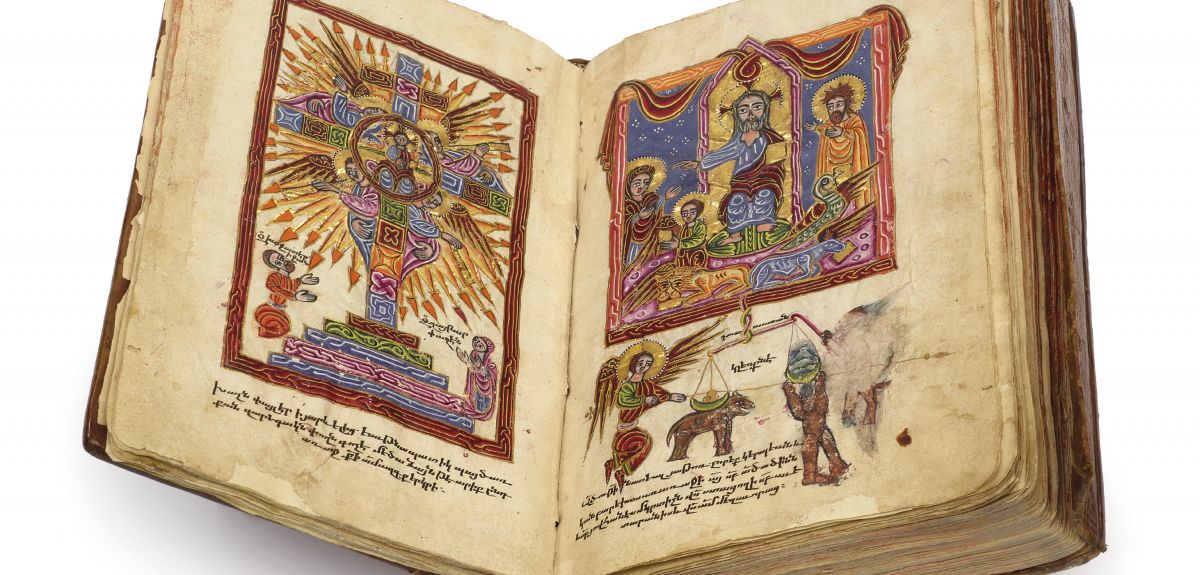

Professor Theo van Lint of the Oriental Institute at Oxford University and Robin Meyer of the Faculty of Classics have curated the display of items from the Bodleian Libraries' Armenian collections, in the first major UK exhibition to focus on Armenian culture in 15 years. The exhibition spans over 2000 years of Armenian history and culture, from the pre-Christian era to the genocide in the early 20th century.

'It's interesting to move from an academic perspective to consider the general public’s knowledge and interest in Armenia,' said Robin Meyer. 'For instance, the ‘Narek’ - the work of an 10th century poet - might not seem accessible, but when people learn that it’s still known and revered today – even learnt by heart – that is something interesting.'

The Narek is a work of poetry by Gregory of Narek, an Armenian saint. The exhibition features an 18th-century printed copy which has been lent by a British Armenian family, for whom the book serves as a 'Saint of the House'. It is kept wrapped in layers of silk and cloth together with other objects of reverence.

'Every step of the process of curation is informative,' said Professor van Lint. 'It involves conservation, publishing, and craftsmanship – for instance, we commissioned cradles to hold the books on display without damaging them.'

The exhibition includes books spanning several millennia, including one which records the earliest known poem in the Armenian language.

The poem, which is recorded in Movsēs Xorenac‘i’s History of the Armenians, recounts the birth of Vahagn, a god of war and part of the Armenian Zoroastrian pantheon. Very few fragments of pre-Christian Armenian poetry survive, and the 'Song of Vahagn', which describes the god's fiery hair and beard, bears some interesting resemblances to Iranian and Indian myths.

2015 marks the centenary of the genocide perpetrated against the Armenian people during World War I.

'Although we've used the anniversary of the genocide as the occasion for this exhibition, we didn’t want just to mourn, but also to use the full wealth of the collections to celebrate thousands of years of Armenian history and culture,' says Professor van Lint.

'We wanted to show that this is a country and a people that has been crucial to the development of culture and trade, and has just as rich and complex a culture as Russia or Italy, for instance, but which is much less well known in Britain.

'Armenia straddles East and West, it exists between Christian and Muslim countries, and there is a depth of human understanding borne out of existing in different circumstances there.

'Christianity underpins Armenian self-perception but there are a number of other influences: I think it’s particularly interesting that there is often a flavour of Zoroastrianism in some of the iconography, particularly with reference to the quality and treatment of light.

'We made an effort to "catch people out" with things they might not expect from a library exhibition,' said Meyer.

As well as books and manuscripts, the exhibition also includes a delicate altar-curtain embroidered in silver and a priest’s staff in the characteristic T-shape, ornamented with snakes. One display case focuses on the pigments used to illuminate books, including gold, plants and poisonous minerals.

'I certainly wouldn’t say that we chose unattractive books and manuscripts, but we didn’t want to select only the ones which immediately spring to mind,' Meyer says.

'We wanted to show the breadth of what has survived over the ages: things which are not just beautiful, but also quite moving. For instance, we have a large handwritten manuscript tracking the history of a family, which was found in 1917 and ends quite abruptly.

'This has not been fully studied, in part because the handwriting is quite difficult to decipher, but there is a lot to learn about the history of the village, including mention of feasts between Muslims and Christians, and other practices which cross boundaries in unexpected ways.'

The free exhibition Armenia: Treasures from an Enduring Culture runs at the Weston Library until 28th February 2016, and is accompanied by a series of public lectures.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest challenges facing global public health, threatening our ability to treat common infections. Cutting-edge research in Oxford University's Department of Chemistry is exploring new ways of administering antibacterial vaccines that could combat growing resistance from bacteria.

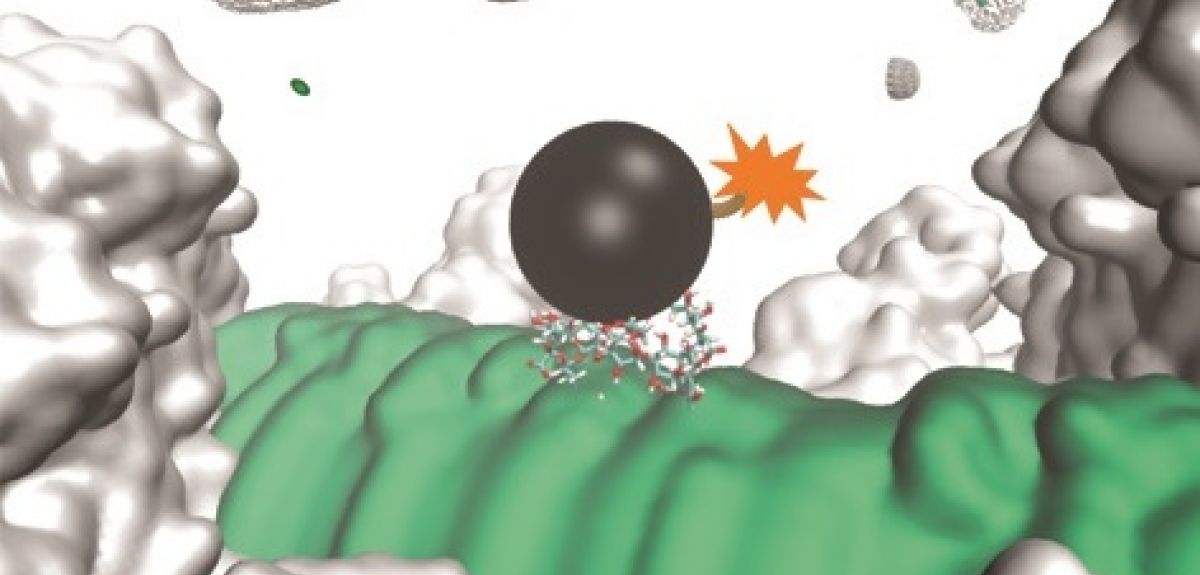

Dr Lingbing Kong is the joint first author (with Dr Balakumar Vijayakrishnan) of a new study, published in Nature Chemistry, exploring a method of vaccination that could circumvent existing resistance pathways by inhibiting, rather than killing, certain species of bacteria. Dr Kong, a member of Professor Ben Davis's research group when the study was carried out, told Science Blog how it all works.

Tell us about the background to your work on antibacterial vaccines

We first started looking at non-toxic antibacterials in 2007. We believed that they might better combat bacterial drug resistance since they do not kill the sensitive bacteria but merely increase their vulnerability in humans. We made our first step through the discovery of the first inhibitor of the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) transporter called Wza, which is common among Gram-negative bacteria. This is the foundation of our antibacterial strategy, which we also call the 'vaccination+block' approach. A report of this early work, carried out under the supervision of Professor Ben Davis and Professor Hagan Bayley, was published in Nature Chemistry in 2013.

How does this potential new vaccine work?

We have been working in collaboration with GlycoVaxyn (now LimmaTech and GSK). The vaccine candidate we developed is targeting a carbohydrate molecule that is common among most Gram-negative bacteria, such as notorious pathogenic bacteria Neisseria meningitidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. This molecule is a tetrasaccharide (four sugar units linked together) found at the base of a polysaccharide, known as a lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS is further covered by the outermost sugar layer, which is composed of CPS.

How could it combat antibiotic resistance?

In order to explain it further, we need to have a look at how the modern drug resistance problem occurred. Most current antibiotics kill bacteria through direct toxicity. There are two key mechanisms through which bacteria can then acquire resistance. In the first, mutations, which evolve over many generations, prevent the antibiotic from functioning. In the other, these mutations are acquired through gene transfer from neighbouring non-sensitive bacterial species.

Currently, the administration of an antibiotic results in the death of sensitive strains and the subsequent complete dominance of resistant strains within the habitat. Increased numbers of resistant bacteria accelerates the spread of resistant bacteria, and ultimately the arrival of multi-drug-resistant bacteria ('superbugs').

Our antibacterial strategy involves the administration of a non-toxic chemical (CPS inhibitor), which destroys the protective outermost CPS layer, exposing the bacteria to attacks by antibodies generated through vaccination. This is followed by cascade immune responses. Our strategy dramatically decreases the occurrence of antibiotic resistance by only killing the pathogenic bacteria within the human body and limiting the optimal effects to occur only after a combined use of vaccination and CPS inhibitor.

Which infections could it target?

We have demonstrated our strategy against infections caused by pathogenic E. coli, with potential against those caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa etc. We expect that our strategy could be extended to infections caused by most, if not all, Gram-negative bacterial pathogens since the CPS inhibitor is a general extracellular inhibitor. We have also demonstrated that after vaccination and upon administration of the CPS inhibitor, the first step of bacterial infections (attachment of bacteria to the host cells) could be prevented. This opens the possibility of rapid treatment of bacterial sepsis.

What are the next steps?

There are a few clear steps for moving forward. For example, we are currently trying to develop the vaccine candidates with larger carbohydrate molecules (more sugar units than the current four-unit molecule) for higher affinity and specificity towards the lipopolisaccharides in bacterial pathogens.

- ‹ previous

- 133 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria