Features

Lockdown learning, with school delivered online, may not be ideal, but it has enabled some highly-unusual lessons to take place. Oxford Classics professors have taken to the internet to engage in ‘Classical Conversations’ with school pupils across the country and the results have excited interest – in all concerned.

The Faculty of Classics Outreach Team has been offering 30 minute classes with an Oxford professor on a Classical subject of the school’s choice – or just a quick-fire question and answer session. And the response was almost immediate – once schools were convinced this offer was ‘for real’. In the last three months, some 600 children at 30 schools from Lancashire to Kent, Norfolk to Wiltshire have taken part. And many more conversations are scheduled over the coming months.

Oxford Classics professors have taken to the internet to engage in ‘Classical Conversations’ with school pupils across the country and the results have excited interest – in all concerned

According to Dr Neil McLynn, head of Classics, the idea was to use the virtual learning of lockdown to ‘zoom' into lessons, in the nicest possible way, giving students a chance to have a conversation with an Oxford expert about their favourite subjects. And, he says, the Faculty has been thrilled.

The project matches primary and secondary school and home-educated students with leading Oxford academics. Topics have ranged from ‘Female characters in the Odyssey’ to ‘Magic and Superstition in Rome’.

But some have been less prosaic, Dr Sophie Bocksberger took part in a Q&A session with a group of primary-aged children. She recalls there were some challenging questions, ‘One boy asked about the toilets in Ancient Greece [he thought everyone would want to know]...somebody else asked if the Greeks had pets and someone asked which was the best god.’

Although such questions would not normally feature in a university Classics course, ‘it was really amazing’, she says. ‘They were really curious about daily life in Ancient Greece and it worked well. I tried to show how we know things, through archaeology or texts, rather than just giving answers.’

One boy asked about the toilets in Ancient Greece...somebody else asked if the Greeks had pets and someone asked which was the best god

Dr Sophie Bocksberger

[In case of interest, toilets were receptacles, emptied into the street, although wealthier Greeks may have sat on marble benches.]

Students, meanwhile, have found the sessions ‘awesome’, ‘really engaging’, ‘very enjoyable’ and ‘fun’, according to their teachers. Many commented that, getting to share their ideas and talk with an Oxford Classicist has, not only, helped them in their current academic work, but has also helped to prepare for the future by giving them an idea of what further classical study might be like.

Dr McLynn also faced a ‘free fire’ round of questions on any subject, but with secondary school pupils. He says, ‘They were full of interest in the Roman world.’

Questions included: who wore togas, farming and food in the UK during Roman times.

‘It was so interesting,’ he says.

A key aim has been to encourage and enthuse school children about the Classics and, the teachers insist, it has been effective

Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson

Some Classical Conversations have centred on the GCSE or A Level syllabuses, with academics sharing their knowledge on topics such as Greek Tragedy, the Parthenon, and the Julio-Claudian Emperors. Others have delved into topics as varied as ‘Persuasive Language in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar’, life in Ancient Egypt, and ‘Feathered Creatures in Mythology’.

In another lesson, Dr McLynn met a group of sixth form Latinists who were studying Juvenal.

‘It involved some very hard questions,’ he remembers.

The project has been received with considerable enthusiasm and imagination in schools and in the university, where the Faculty is keen to encourage applications from a wide variety of applicants – even those without experience of Classics.

One Q&A, involving Professor Peter Stewart and a group of Classical Civilisation students, took place in a virtual ancient theatre. And Professor Armand D’Angour chatted with a class of secondary students about Ancient Greek music.

Dr Gail Trimble, meanwhile, says, ‘It has been really effective...the students have a chance to talk about the subject in a broader way and, for me, joining a lesson without being a ‘visitor’ in a school, having to be looked after, has meant schools got more out of it.’

They talked about heroism and the Roman political context – giving students a taste of what Classics at university might be like

Dr Gail Trimble

She spoke with a group of year 12s, who are studying Virgil’s Aeneid, and they had some ‘very bright questions’. She says, rather than looking narrowly at the text as though it were an A level lesson, they talked about heroism and the Roman political context – giving students a taste of what Classics at university might be like.

Schools too are very positive. According to one school, it was ‘very much a conversation – we could ask questions and input our own ideas whilst being guided and taught’, which meant that ‘the conversation was open to lots of different avenues and interpretations.’

Meanwhile, a teacher says, our Oxford expert ‘answered all questions with humour and intelligence and the students really loved it. I think they also loved having an expert in the field.’

Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson, Research Fellow in Classics Education, says. ‘These 30-minute sessions offer students different viewpoints and ideas to enrich their knowledge and enjoyment of the topic. They might add detail or draw links between different parts of the literature, art and history which they find interesting.’

A key aim of the project has been to encourage and enthuse school children about the Classics and, the teachers insist, it has been effective. The potential for sparking interest is what energises the Classics team.

During school years, there can be moments of direct personal contact with people outside of school which can be transformative

Dr Neil McLynn

Dr McLynn maintains, ‘During school years, there can be moments of direct personal contact with people outside of school which can be transformative.‘

You can find out more about the project here https://clasoutreach.web.ox.ac.uk/classical-conversations.

If teachers would like to request a Classical Conversation, please email [email protected]. Preference will be given to state-maintained schools but we welcome requests from all teachers.

- Ground-breaking research project follows 12,000 from infancy to adulthood

- Across four countries and three continents

- Findings reveal huge changes in poverty, education and expectations

- Study has led to changes in law, and policy

- Massive open access data source for international researchers

When Young Lives started in 2001, it was supposed to be a 15-year project, tracking the lives of children from age one to 15 in four developing countries, in line with the UN’s Millennium Development Goals.

This is 7-Up writ very large, the project encompasses 12,000 young people and, for 20 years, has tracked the lives of children in four developing countries

The sample was selected to over-represent the poorest areas, but covers the diversity of study countries: Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states), Peru and Vietnam. It was intended to be a rich seam of information, with children and their families personally interviewed, to investigate how the experience of poverty and inequality early in life affects what happens later in life, and what difference it makes being born a girl or a boy.

Copyright: Young Lives/Sarika Gulati.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years...early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.

Copyright: Young Lives/Sarika Gulati.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years...early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.Young Lives has now completed five rounds of an in-person household survey, and one by phone in 2020, interspersed with four waves of further in-depth, qualitative interviews. According to deputy director Young Lives at work, Dr Marta Favara, ‘We have carried out a face-to-face survey every three to four years. Interviewers return to the same families to capture changes in their lives and communities.’

In each round, every child is visited at home. It takes around 2 ½ hours and can involve more than one visit by local researchers, some of whom have been with the project from the beginning. Senior research officer, Dr Gina Crivello, explains that the research is carried out by in-country partners, ‘We have a very strong relationship with our research partners... they maintain the relationships with the families which is so important for long-term research.’

She adds, ‘It’s very much a collaborative project.’

The interview questions are crafted to draw out the young lives, including physical growth, cognitive development, health, social and emotional well-being, education, life skills, work, marriage and children and how they feel about their lives and futures.

The more in-depth interviews involve a 200-strong sub-set of the group. Dr Crivello explains these are less-structured conversations, to find out from the young people what matters most to them. She says, ‘We dig deeper to find out what lies behind the statistics emerging from the household survey – if children are dropping out of school, we can use these interviews to find out what is going on.’

One important aspect of the research, according to Dr Favara is, ‘From the beginning, Young Lives talked to the children, who are, after all, experts in their own lives. Most studies about poverty only speak to adults. But children and parents don’t always have the same experiences or think alike.'

And the study has provided a wealth of information about how children’s lives have changed over the last two decades. First and foremost, evidence has found significant improvement in the living standards of many Young Lives families, alongside rapid economic growth and significant poverty reduction.

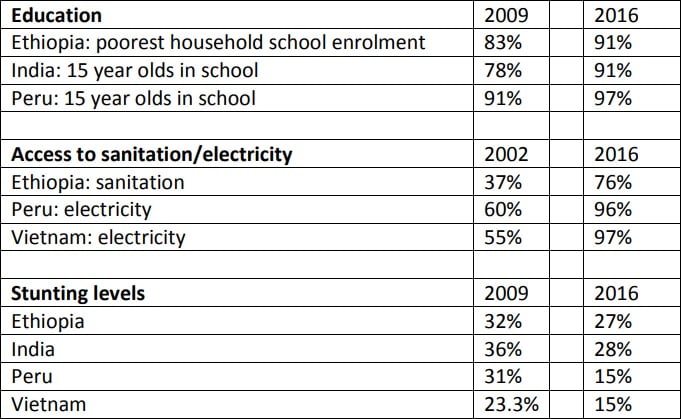

In Ethiopia, extreme poverty declined from 61% in 1996 to 24% in 2016. And many Young Lives families reported improved access to basic services, electricity, water and sanitation. In Peru, the proportion of Young Lives families with access to electricity increased from 60% in 2002 to 96% in 2016.

The study has witnessed important improvements in education.

©Young Lives/Lucero Del Castillo Ames.

The study has witnessed important improvements in education.

©Young Lives/Lucero Del Castillo Ames.

Seven main conclusions from the study so far, according to the two researchers are:

Early childhood is absolutely critical. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life shape what comes next. A malnourished child is more likely to have weaker cognitive abilities by age five. A child arriving at school already disadvantaged will fall further behind as they grow up.Poverty is all encompassing. The study confirms childhood poverty is multi-dimensional and reaches into every part of a child’s life, limiting their potential in many ways.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years. The study has challenged the assumption that persistent malnutrition irreversibly affects cognitive development. Evidence showed children, who physically recover as they age, also perform better in cognitive tests. And early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.

Education attendance did not always result in the hoped for life changes. Across the four countries, 40% of the sample had not established basic literacy by the age of eight, despite attending school, with many only able to access poor quality education.

Early marriage and childbearing have a negative impact on life chances. Early marriage and childbearing affect young mothers’ education and employment chances, as well as the health and cognitive development of their children.

Violence towards children has a profound impact on their lives. This finding saw a change in the law in Peru’s schools to protect children from violence.

Not all work is detrimental to children. No child should undertake harmful work or work that prevents them from attending school. Some families depend on children’s contributions and, when safe, their work can bring important rewards for themselves and their families.

The ground-breaking nature of the survey, with the data open access, gives international researchers the chance to study the lives of thousands of young people in developing countries.

Over 20 years, the study has witnessed important improvements in education, with more access to primary education, secondary education and closing of the education gender gap. But progress remained slower for children born in the poorest households.

The dramatic and on-going shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has raised major concerns about whether improvements will be sustained over time. The 2020 phone survey found lockdowns and related restrictions could not only halt progress made over the last two decades, but could also reverse life chances and entrench persisting inequalities.

Young Lives will find out what happens next. Dr Favara says another phone survey is planned for 2021, to research the mid-term effect of the pandemic, as well as two further survey rounds and is fundraising for more in-depth interviews.

Follow the Young Lives story on Twitter @yloxford, Facebook and LinkedIn.

All the images are of children living in circumstances and communities similar to the children in our study sample

By Professor Jane McKeating, Nuffield Department of Medicine

Our lives are so often dictated by time - it seems like we are not the only ones.

Most living things are aware of the time of day and respond through endogenous biological rhythms, with an approximate cycle of 24 hours. This “circadian clock” controls a range of biological processes including hormone secretion, metabolic cycling and immune protection against pathogens. More recently, the circadian clock has been shown to influence viral infection by altering the host pathways essential for their replication.

Circadian rhythms are everywhere and so are viruses - the interaction between them is both incredibly fascinating and perhaps unsurprising.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a globally important pathogen, with over 270 million individuals infected and at risk of developing liver disease or cancer. A cure for this virus is urgently needed. Dr Xiaodong Zhuang, researcher in the McKeating Group laboratory, recently showed that circadian rhythms influence HBV replication. This research found that the key circadian transcription factor (BMAL1) binds the HBV genome. This ‘intimate’ virus-host interaction promotes viral infection in cells and in animals models, providing exciting avenues for the discovery of new anti-viral drugs. Interesting questions remain to be answered as to whether HBV infection can 'reset' the clock and how this may impact liver cancer development.

Being in synchrony with your body might mean being in synchrony with your viruses.

The circadian clock is thought to be around 2.5 billion years old, tracing back to the cyanobacteria that released vast amounts of oxygen during the Great Oxidation Event. Interestingly, many of the elements of our oxygen sensing systems are homologous to those we use for sensing time, and there is growing evidence of an interplay between the circadian and hypoxia signalling pathways.

Work from the same lab by Dr Peter Wing and colleagues recently found that this ancient oxygen sensing system promotes HBV replication through the well-defined hypoxia induced factors. Has HBV co-evolved to use these two ancient pathways (circadian clock and oxygen sensing) to infect the liver? It seems plausible that such interactions will be found for many other viruses.

To find out more about circadian rhythms and HBV, read the full paper published in Nature Communications.

By Dr Nisreen Khambati, Oxford Vaccine Group

Every year, more than one million children fall ill with tuberculosis (TB) globally, and about a quarter die from this potentially preventable and curable disease. According to the World Health Organization, TB is one of the ten most frequent causes of death among children under five years of age.

The main challenge remains the correct and timely diagnosis of TB, especially in resource-constrained settings. TB is more difficult to diagnose in children compared to adults because there are far fewer TB bacteria present in children than in adults. This means that in many children the diagnosis of TB is missed.

To test young children for TB, we currently need to collect mucus from the lungs (sputum) or liquid contents of the stomach which are difficult to obtain from children and must be collected in a hospital. Diagnosis of TB in children with HIV infection is even more difficult and they are more likely to develop TB compared to children not infected with HIV. Despite advances in TB diagnostic tests in the last decade, these have not impacted significantly on paediatric TB. New and different ways to diagnosis TB in children are urgently needed, especially for those infected with or exposed to HIV.

An international collaboration of researchers is now conducting an exciting large diagnostic study in Uganda to fill this research gap. The NOD for TB study (Novel and Optimized Diagnostics in Paediatric Tuberculosis) aims to evaluate and develop new tests for TB among children under five years of age. Uniquely, the study aims to detect the TB bacteria in body fluids such as blood, urine, stool and saliva that are easier to collect from children than sputum or stomach contents.

The study will also evaluate tests looking at the body’s immune response to the disease that have not been studied in large populations of young children before. NOD for TB is currently being set up in Kampala, Uganda and will start recruiting children with suspected TB in April 2021 for the next five years. Children who are HIV negative and HIV positive will both be recruited.

'We are excited to launch this important study which will evaluate a broad range of innovative new approaches and tests to diagnose TB in children under 5,' says Dr Rinn Song, clinical scientist at the Oxford Vaccine Group, Department of Paediatrics, and study lead for Oxford. 'Our hope is that findings of this study will contribute to address the urgent need to reduce the high number of preventable and tragic deaths of infants and young children due to TB in the world.'

Paediatric TB is underdiagnosed and has a high mortality rate. Gains in the global fight against TB have been threatened due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Promising and accessible new tests are urgently required and need to be evaluated in children less than five years of age, who are most vulnerable and difficult to diagnose. The NOD for TB study in Uganda aims to achieve this critical challenge. The clock is ticking.

NOD for TB is funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health and led by Professor Jerrold Ellner, Professor David Alland and Professor Padmini Salgame of Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and Professor Moses Joloba and Professor Adeodata Kekitiinwa in Kampala. This consortium is comprised of an international group of clinical, translational and laboratory-based scientists, including Rutgers University, Baylor Children’s Clinical Center of Excellence in Kampala, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics in Geneva, Frontiers Science, the US CDC, KEMRI, McGill University, the Medical University of South Carolina and Oxford University. The local Ugandan team at Baylor Children’s Clinical Center of Excellence where the study will start is led by Dr Grace Kisitu and Dr Emmanuel Nashinghe.

It has generally been accepted that economic competence is a core concern of all voters. But new research, published recently in Politics and Society, shows this is not always the case.

Study author, Dr Tim Vlandas, of Oxford’s Department of Social Policy and Intervention, maintains, voters are far more complex – and likely to vote for incumbents, depending on how economic performance affect them specifically, rather than based on a general evaluation of the economy.

The study broadens the scope of economic voting research by investigating how the electoral impact of the economy varies by social group in terms of how particular dimensions of economic performance affects them, not just in terms of general competence.

High unemployment, price rises or austerity do not necessarily spell political disaster...Conversely, greater public spending and low unemployment may not automatically translate into popularity

Dr Vlandas argues voters react in distinct ways to different aspects of economic performance, as they affect them personally to varying degrees. As a result, high unemployment, price rises or austerity do not necessarily spell political disaster if certain groups of politically powerful voters are not directly affected. Conversely, greater public spending and low unemployment may not automatically translate into popularity. Thus, voters penalise incumbent politicians to varying extents, depending on their personal exposure to specific dimensions of economic deterioration.

Dr Vlandas says, ‘Prevailing wisdom suggests that poor economic performance has a negative effect on the re-election chances of political incumbents, either because it signals a lack of competence or because it has an effect on voters’ lives.

‘However, this expectation is subject to conflicting results...In this paper, we build on the emerging idea of heterogeneity among electorates which challenges the assumption that all voters can be thought of as penalising incompetence in a similar way.’

According to the paper, ‘Different social groups have different risk profiles and distinct economic and welfare state policy preferences, which have important implications for electoral behaviour...[for instance] the expected electoral response to austerity policies is heavily contingent on individuals’ socioeconomic resources to withstand cutbacks in government programs.’

Margaret Thatcher’s relatively poor economic performance in terms of unemployment did not prevent her from getting re-elected multiple times, according to the study.

The paper points to one UK politician who was re-elected despite [or, perhaps, because of] economic misery, ‘Margaret Thatcher’s relatively poor economic performance in terms of unemployment did not prevent her from getting re-elected multiple times.’

However, her continuing success, according to the paper ‘could have been the result of economic policies that primarily hurt the low-skilled and the poor, while potentially benefiting some high-income voters and the elderly’.

The article maintains it is the individual’s experience, rather than the politician’s perceived competence, which is key, ‘The electoral impact of deteriorating economic performance is largely contingent on individuals’ risk profiles, with pensioners appearing particularly responsive to retrospective inflation performance, low-skilled workers to unemployment levels, public sector workers and low-skilled workers to public sector cuts, and high-income individuals to developments in the stock market.’

Dr Vlandas adds, ‘Public spending primarily affects the probability of voting for incumbents both among public sector and low-skilled workers, while it influences the electoral decisions of pensioners and high-income earners considerably less so or not at all.’

Public spending primarily affects the probability of voting for incumbents among public sector and low-skilled workers, while it influences...pensioners and high-income earners considerably less so or not at all

Dr Tim Vlandas

But, he says, ‘The opposite pattern emerges with variation in stock market performance: high-income earners and pensioners are highly responsive to stock market returns, whereas public sector and low-income workers are largely unaffected by them.’

The research found incumbent politicians can be affected, ‘Voters are more likely to turn their back on incumbents when certain aspects of the economy deteriorate that are of particular importance for the social groups to which they belong.’

Dr Vlandas says, ‘With pre-electoral unemployment rates...propensity to vote for incumbents declines somewhat more rapidly among the ranks of low-skilled workers,... [But] The group-specific response to inflation marks a clear divide between pensioners and the rest of the population, with the former systematically penalising incumbents during inflationary electoral contexts.’

The findings, say the authors, empirically demonstrate the heterogeneity of social groups in their economic voting patterns, strengthening the electoral link between group-specific policy preferences and government policies.

The paper provides a novel explanation for why there is so little evidence on systematic electoral punishment against governments that undertake policies, such as fiscal adjustment and austerity, that are detrimental for growth (at least in the short run): it is only a subset of the population that is responsive to economic outcomes that are conventionally presumed to capture the economic vote, with other variables being equally important pieces of the full economic voting picture.

The study looked at four social groups (low-skilled workers, pensioners, public sector employees and high-income individuals) and four economic variables (unemployment, inflation, stock market performance and public spending).

Co-written with Dr Abel Bojar from the European University Institute, the paper can be seen here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0032329221989150.

- ‹ previous

- 28 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria