20-year Oxford study follows 12,000 Young Lives in developing world

- Ground-breaking research project follows 12,000 from infancy to adulthood

- Across four countries and three continents

- Findings reveal huge changes in poverty, education and expectations

- Study has led to changes in law, and policy

- Massive open access data source for international researchers

When Young Lives started in 2001, it was supposed to be a 15-year project, tracking the lives of children from age one to 15 in four developing countries, in line with the UN’s Millennium Development Goals.

This is 7-Up writ very large, the project encompasses 12,000 young people and, for 20 years, has tracked the lives of children in four developing countries

The sample was selected to over-represent the poorest areas, but covers the diversity of study countries: Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states), Peru and Vietnam. It was intended to be a rich seam of information, with children and their families personally interviewed, to investigate how the experience of poverty and inequality early in life affects what happens later in life, and what difference it makes being born a girl or a boy.

Copyright: Young Lives/Sarika Gulati.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years...early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.

Copyright: Young Lives/Sarika Gulati.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years...early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.Young Lives has now completed five rounds of an in-person household survey, and one by phone in 2020, interspersed with four waves of further in-depth, qualitative interviews. According to deputy director Young Lives at work, Dr Marta Favara, ‘We have carried out a face-to-face survey every three to four years. Interviewers return to the same families to capture changes in their lives and communities.’

In each round, every child is visited at home. It takes around 2 ½ hours and can involve more than one visit by local researchers, some of whom have been with the project from the beginning. Senior research officer, Dr Gina Crivello, explains that the research is carried out by in-country partners, ‘We have a very strong relationship with our research partners... they maintain the relationships with the families which is so important for long-term research.’

She adds, ‘It’s very much a collaborative project.’

The interview questions are crafted to draw out the young lives, including physical growth, cognitive development, health, social and emotional well-being, education, life skills, work, marriage and children and how they feel about their lives and futures.

The more in-depth interviews involve a 200-strong sub-set of the group. Dr Crivello explains these are less-structured conversations, to find out from the young people what matters most to them. She says, ‘We dig deeper to find out what lies behind the statistics emerging from the household survey – if children are dropping out of school, we can use these interviews to find out what is going on.’

One important aspect of the research, according to Dr Favara is, ‘From the beginning, Young Lives talked to the children, who are, after all, experts in their own lives. Most studies about poverty only speak to adults. But children and parents don’t always have the same experiences or think alike.'

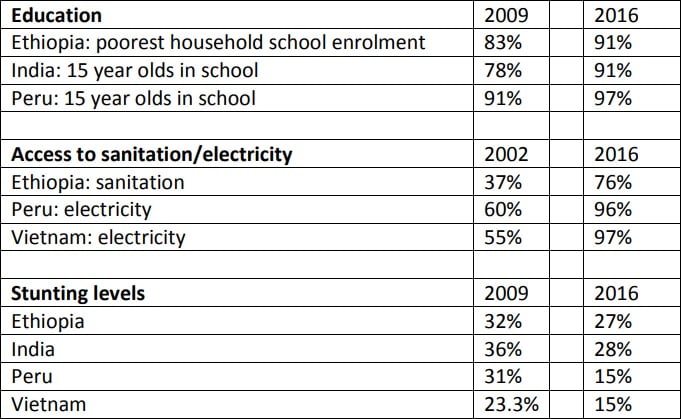

And the study has provided a wealth of information about how children’s lives have changed over the last two decades. First and foremost, evidence has found significant improvement in the living standards of many Young Lives families, alongside rapid economic growth and significant poverty reduction.

In Ethiopia, extreme poverty declined from 61% in 1996 to 24% in 2016. And many Young Lives families reported improved access to basic services, electricity, water and sanitation. In Peru, the proportion of Young Lives families with access to electricity increased from 60% in 2002 to 96% in 2016.

The study has witnessed important improvements in education.

©Young Lives/Lucero Del Castillo Ames.

The study has witnessed important improvements in education.

©Young Lives/Lucero Del Castillo Ames.

Seven main conclusions from the study so far, according to the two researchers are:

Early childhood is absolutely critical. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life shape what comes next. A malnourished child is more likely to have weaker cognitive abilities by age five. A child arriving at school already disadvantaged will fall further behind as they grow up.Poverty is all encompassing. The study confirms childhood poverty is multi-dimensional and reaches into every part of a child’s life, limiting their potential in many ways.

There is a ‘second chance’ in teenage years. The study has challenged the assumption that persistent malnutrition irreversibly affects cognitive development. Evidence showed children, who physically recover as they age, also perform better in cognitive tests. And early action in adolescence, ‘can reverse the effect’ of earlier malnutrition on poor learning.

Education attendance did not always result in the hoped for life changes. Across the four countries, 40% of the sample had not established basic literacy by the age of eight, despite attending school, with many only able to access poor quality education.

Early marriage and childbearing have a negative impact on life chances. Early marriage and childbearing affect young mothers’ education and employment chances, as well as the health and cognitive development of their children.

Violence towards children has a profound impact on their lives. This finding saw a change in the law in Peru’s schools to protect children from violence.

Not all work is detrimental to children. No child should undertake harmful work or work that prevents them from attending school. Some families depend on children’s contributions and, when safe, their work can bring important rewards for themselves and their families.

The ground-breaking nature of the survey, with the data open access, gives international researchers the chance to study the lives of thousands of young people in developing countries.

Over 20 years, the study has witnessed important improvements in education, with more access to primary education, secondary education and closing of the education gender gap. But progress remained slower for children born in the poorest households.

The dramatic and on-going shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has raised major concerns about whether improvements will be sustained over time. The 2020 phone survey found lockdowns and related restrictions could not only halt progress made over the last two decades, but could also reverse life chances and entrench persisting inequalities.

Young Lives will find out what happens next. Dr Favara says another phone survey is planned for 2021, to research the mid-term effect of the pandemic, as well as two further survey rounds and is fundraising for more in-depth interviews.

Follow the Young Lives story on Twitter @yloxford, Facebook and LinkedIn.

All the images are of children living in circumstances and communities similar to the children in our study sample