Features

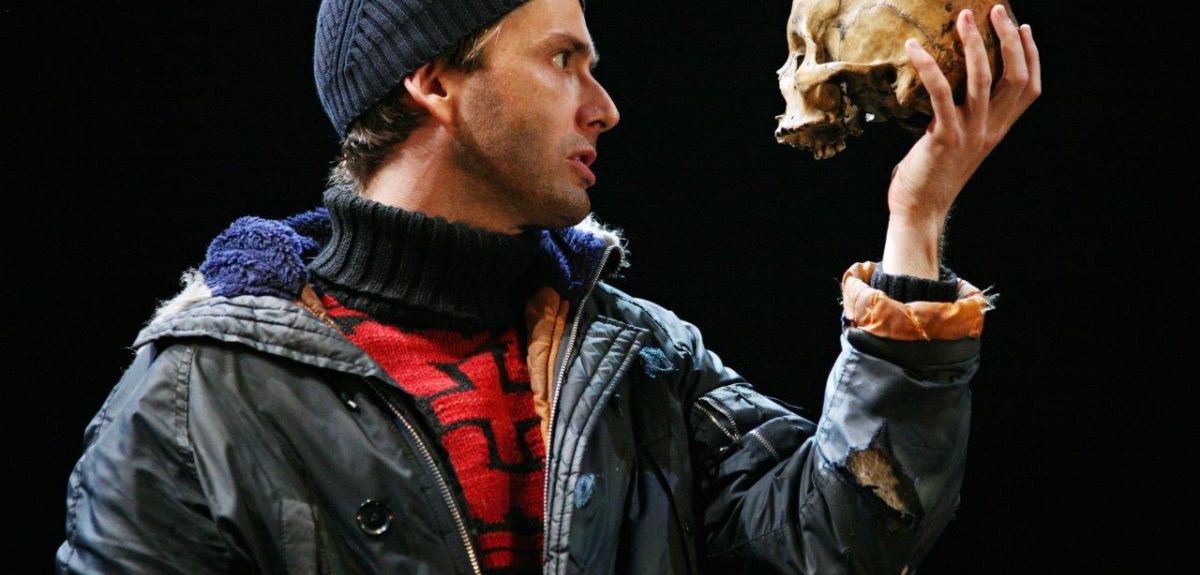

Playwright David Edgar has been announced as this year's Humanitas Visiting Professor of Drama Studies at Oxford University.

He will discuss the future of the playwright in a week-long series of talks and discussions next month.

Mr Edgar said: 'A huge change is happening in British theatre. Throughout the last century, theatre programmes were dominated by revivals. Now, for the first time for at least a hundred years, new work has overtaken old work in the repertoire.

'At the same time, however, there has been a shift of opinion against playwriting, in favour of collective methods of theatre. The very activity of playwriting has been attacked as individualistic, undemocratic and even immoral.

'I'm running a week of events to explore the causes and consequences of the anti-writer trend. Is it happening? Do the charges against the playwright stack up? Can playwrights work effectively in a collective framework? What effect is the controversy having on the theatre ecology as a whole?

'Over the first week in February, I’m bringing together a group of playwrights, theatre practitioners and critics to discuss whether the playwright is dead, and – if not – what the challenge to his and her status will have on the theatre as a whole.'

Mr Edgar will take part in a number of events from Monday 2 February to Saturday 7 February, which are free and open to the public. On Monday he will give a lecture which presents the case for the individual playwright, but also discusses whether the primacy of the playwright is outdated and what playwrights can learn from alternative playmaking methods.

On Wednesday he will discuss the dramatist’s working methods with playwrights April de Angelis and David Greig. On Friday he will explore how playwrights collaborate in a conversation with Howard Brenton, and Bryony Lavery. On Saturday he will lead a debate on the challenge to traditional roles and hierarchies in the theatre, with critic Michael Billington, playwright Rachel De-lahay, theatremaker Chris Goode and academic Dr Liz Tomlin.

David Edgar is a renowned playwright who has written for theatre, television, radio and film. In 1989, he founded Britain's first graduate playwriting course, at the University of Birmingham, of which he was director for ten years. He was appointed as Britain's first Professor of Playwriting in 1995. His book about playwriting, How Plays Work, was published by Nick Hern Books in 2009.

The Professorship is hosted at Brasenose College by Dr Sos Eltis of the English Faculty. Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities. Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue with the support of a series of generous benefactors and administered by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

What has the Bodleian received for Christmas? A spectacular travel-sized library that once belonged to Prince Charles, later King Charles I.

It has been bequeathed by John McLaren Emmerson, DPhil (Oxon), to mark the part played by the University and City in the English Civil War, and in grateful recollection of many enjoyable and informative visits to the Bodleian.

This latest addition to the Bodleian Libraries collection is like a 17th century version of a Kindle. Two red leather cases, designed in the 1970s by Sangorski and Sutcliffe to look like two large books, open up to reveal 59 small volumes covering just about everything that a wealthy educated gentleman would want to read on his travels.

Charles I's travelling library arrived at the Bodleian last week and was acquired through a bequest. The collection of tiny books have gold-tooled bindings and some are believed to have been signed by the Prince himself. Titles include classical texts by the poet Ovid and the philosopher Cicero as well as bibles and religious books such as De Imitatione Christi by Thomas A Kempis.

Travelling libraries are believed to have become popular among wealthy bibliophiles in the 1600s after MP William Hakewill commissioned four such libraries to be made for his friends and patrons. A little is already known about the Prince's portable library but staff in the Bodleian's Rare Books Department hope to discover more about its provenance through their research over the coming months.

The proportion of the Earth's crust that may be capable of supporting life could be much greater than previously thought.

That's according to new research into the hydrogen-rich waters trapped in rock fractures kilometres below the Earth's surface [see this nice BBC piece].

Hydrogen is food for microbes and vital to many deep ecosystems. Now researchers from University of Toronto, Oxford University, and Princeton report in Nature how they used data from 19 different mining sites in Canada, Africa, and Scandinavia to map ancient hydrogen-rich waters locked in Precambrian Shield rocks.

With Precambrian rocks making up more than 70% of the Earth’s crust the researchers calculate that reactions within these rocks could be producing the same amount of hydrogen as the total amount created on the ocean floor (by features such as hydrothermal vents).

I asked study author Professor Chris Ballentine of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences about the importance of hydrogen and what implications this new research has for life on Earth and the search for life on other planets…

OxSciBlog: Why is understanding global hydrogen production important?

Chris Ballentine: Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the Universe, rarely occurs on Earth in a pure di-molecular form (H2) and is mostly found today in its chemically oxidised form, water (H2O). In part this is because hydrogen is light enough to escape Earth's gravity and so is not retained in Earth's atmosphere.

Hydrogen is also very reactive and releases energy when it reacts. Microbes, kilometres down in the continental crust, release the energy trapped in dissolved hydrogen in ancient fracture waters as a key part of their food chain. By understanding the availability and location of hydrogen in the Earth we can build a picture of how important this source of energy is for sustaining life on and in Earth today and in the past.

OSB: What does your study reveal about how much/where hydrogen is produced?

CB: Until now, the scientific communities' attention has been focussed on the hydrogen and associated microbes in the Earth's crust lying under the oceans. Hydrogen production in the continental crust was previously thought to be relatively minor and any role it plays in supporting microbial life similarly small.

We have shown with abundant observations and new calculations that the combination of water reacting with iron rich rocks and natural radioactivity breaking water into oxygen and hydrogen (radiolysis) together produce in the continental crust an amount of hydrogen equal to that produced by the oceanic crust.

OSB: What are the implications for searching for deep microbial life on Earth?

CB: In geological terms the continental crust is much older, deeper and more stable than oceanic crust which rarely survives longer than 200 million years. We have already shown using techniques developed by my team (Nature 2013) that at least one deep continental environment with the right chemistry to support life may have been isolated from the surface for billions of years. This is on planetary timescales (The Earth is about 4.56 billion years old) and our work now shows that hydrogen production is at a sufficient level to support life as a general rather than an isolated or exotic phenomenon in the stable continents.

OSB: How might it help in the search for life on other planets?

CB: The basic chemistry and physics on rocky planets similar to Earth will also be the same. Any planet that has supported surface water is likely to retain water in the deeper rock pore spaces if it preserves an old crust. Mars is such a planet whereas Venus's crust is much younger and likely lost any water.

Over time, water will react with some of the rock to produce hydrogen at rates able to support microbial life. Reactions with hydrogen can be catalysed by some rocks to produce light hydrocarbons and provides a rich chemistry or menu for microbes. We now know there is ample material and energy for microbial communities to exist. Deep environments can be protected from surface processes such as meteorite bombardment and planetary atmosphere loss.

These devastating processes, while removing life from the planetary surface, might leave life to survive in the deep crust, warmed by deep planetary heat and natural radioactivity.

OSB: What's the next step in this research?

CB: Access to fluids from the deepest parts of the continental crust from deep mines are becoming more available. Our consortium are developing with the funding organisation (the Deep Carbon Observatory), an international network of sites where we can build a full understanding of the nature and age of habitats in the continents that might support microbial life.

The type of microbes that are found in the deep continental crust is still in a discovery phase, but this is making us ask questions such as how does life get established, how does it survive and evolve and how might it play a role in seeding life in other parts of the Earth. How does it compare, for example, to the microbial communities in the younger oceanic crust feeding on a similar energy chain and indeed different parts of the continental system?

We know from plate tectonics that some regions of the crust are stable for billions of years, but when continents collide fluids can migrate huge distances, perhaps carrying and seeding life from such deep biological planetary nurseries both to other regions of the crust and also to the surface.

A trip to the northernmost tip of the British Isles resulted in an unusual photo opportunity.

Leejiah Dorward, an Oxford University DPhil student studying human-wildlife conflict at the Environmental Research DTP, visited the Hermaness Nature Reserve whose cliffs are home to around 20,000 pairs of puffins, 12,000 pairs of Northern Gannets, as well as fulmars, kittiwakes, guillemots, razorbills, shags, and gulls.

It was there that Leejiah took the photo above that was recently highly commended in the British Ecological Society photo competition.

He tells me: 'While aware that Hermaness was an important breeding site for a number of bird species, we were not prepared for the full assault on our senses that awaited us as we arrived at the cliff tops. Looking down over the thousands of birds squabbling on the cliffs or soaring over a rough sea 170 metres below. The strong updrafts these birds were riding also bringing with it the acrid stench of guano that stains much of these cliffs white.'

Along with a couple of friends Leejiah perched on the grass above the cliffs and was quickly mesmerised by the sheer numbers of birds flying above, below and all around:

'The effort I had expended cycling up Shetland's hilly roads with my heavy camera gear was soon rewarded with gannets, fulmars and skuas all performing wonderfully for the camera. Unfortunately time was against us as we had many more miles to cycle that day before reaching our beds for the night so we had to tear ourselves away from the cliffs and head back to the road, however it was a real joy and pleasure to be able to watch and photograph these majestic birds.'

A walking molecule, so small that it cannot be observed directly with a microscope, has been recorded taking its first nanometre-sized steps.

It's the first time that anyone has shown in real time that such a tiny object – termed a 'small molecule walker' – has taken a series of steps. The breakthrough, made by Oxford University chemists, is a significant milestone on the long road towards developing 'nanorobots'.

'In the future we can imagine tiny machines that could fetch and carry cargo the size of individual molecules, which can be used as building blocks of more complicated molecular machines; imagine tiny tweezers operating inside cells,' said Dr Gokce Su Pulcu of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry. 'The ultimate goal is to use molecular walkers to form nanotransport networks,' she says.

However, before nanorobots can run they first have to walk. As Su explains, proving this is no easy task.

For years now researchers have shown that moving machines and walkers can be built out of DNA. But, relatively speaking, DNA is much larger than small molecule walkers and DNA machines only work in water.

The big problem is that microscopes can only detect moving objects down to the level of 10–20 nanometres. This means that small molecule walkers, whose strides are 1 nanometre long, can only be detected after taking around 10 or 15 steps. It would therefore be impossible to tell with a microscope whether a walker had 'jumped' or 'floated' to a new location rather than taken all the intermediate steps.

As they report in this week's Nature Nanotechnology, Su and her colleagues at Oxford's Bayley Group took a new approach to detecting a walker's every step in real time. Their solution? To build a walker from an arsenic-containing molecule and detect its motion on a track built inside a nanopore.

Nanopores are already the foundation of pioneering DNA sequencing technology developed by the Bayley Group and spinout company Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Here, tiny protein pores detect molecules passing through them. Each base disrupts an electric current passed through the nanopore by a different amount so that the DNA base 'letters' (A, C, G or T) can be read.

In this new research, they used a nanopore containing a track formed of five 'footholds' to detect how a walker was moving across it.

'We can't 'see' the walker moving, but by mapping changes in the ionic current flowing through the pore as the molecule moves from foothold to foothold we are able to chart how it is stepping from one to the other and back again,' Su explains.

To ensure that the walker doesn't float away, they designed it to have 'feet' that stick to the track by making and breaking chemical bonds. Su says: 'It's a bit like stepping on a carpet with glue under your shoes: with each step the walker's foot sticks and then unsticks so that it can move to the next foothold.' This approach could make it possible to design a machine that can walk on a variety of surfaces.

It's quite an achievement for such a tiny machine but, as Su is the first to admit, there are many more challenges to be overcome before programmable nanorobots are a reality.

'At the moment we don’t have much control over which direction the walker moves in; it moves pretty randomly,' Su tells me. 'The protein track is a bit like a mountain slope; there's a direction that's easier to walk in so walkers will tend to go this way. We hope to be able to harness this preference to build tracks that direct a walker where we want it to go.'

The next challenge after that will be for a walker to make itself useful by, for instance, carrying a cargo: there’s already space for it to carry a molecule on its 'head' that it could then take to a desired location to accomplish a task.

Su comments: 'We should be able to engineer a surface where we can control the movement of these walkers and observe them under a microscope through the way they interact with a very thin fluorescent layer. This would make it possible to design chips with different stations with walkers ferrying cargo between these stations; so the beginnings of a nanotransport system.'

These are the first tentative baby steps of a new technology, but they promise that there could be much bigger strides to come.

- ‹ previous

- 157 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?