Features

Economic 'games' routinely used in the lab to probe people's preferences and thoughts find that humans are uniquely altruistic, sacrificing money to benefit strangers. A new study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests that people don't actually play these games in the way researchers expect, and finds no evidence for altruistic behaviour.

'These results do not necessarily mean that humans are selfish rather than altruistic', cautions lead author Dr Maxwell Burton-Chellew from the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford, 'But they do mean that current evidence cannot support claims about humans being altruistic in these laboratory experiments. While the previous results are robust and were replicated by our study, once you put in the proper controls, the previous interpretations of these results no longer stand up.'

I asked him about what these results are likely to mean for the field.

OxSciBlog: What do these economic games involve?

Maxwell Burton-Chellew: In the 'public goods' game that we and others have used, we bring a group of people into the lab, and we tell them that they're playing a game with other people, and that they have the chance to earn some money. They play anonymously through a computer, so they don't see each or talk to each other. They all have an initial sum of virtual money (which gets paid for real at the end), and they can either keep this money, or invest it in a common pot. Putting money into the common pot is more efficient, since we double the total contributions, but the people who benefit are the other players: the money gets divided equally, regardless of individual contributions. The volunteers play this game again and again, and we don’t spell it out to them that investing is personally costly, although this information is in the instructions.

OSB: What have others found using these games?

MBC: The way to win the most money in this game is to be a 'free-loader': even if a player doesn't invest anything at all in the common pot, they still get an equal share of what everyone has contributed, so the 'rational' thing to do is to just keep all the money, and not contribute anything at all into the common pot.

However, this is not what people actually do - they still invest money into the common pot, even when they could calculate, after playing the game again and again, that they are getting less than they are putting in. Previous work has assumed that this is because people are altruistic: willing to help others at personal cost. This was surprising because traditional economic theory holds that organisms (including humans) are rational: they make consistent choices, making use of all available information, and they are self-interested, prioritizing their own interests above others.

But the Nobel prize-winning work from Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed that people are not always consistent in their decisions, and instead have all sorts of cognitive biases, leading to imperfect choices that limit their own welfare. This idea is now widely accepted: we know that people are not robots.

Now, more recent work appears to show that people are not self-interested either, overturning what is left of the idea of rational choices. However, to conclude that, you have to assume that people are making use of all the information in the instructions: working out in advance that they will make a loss, and then going ahead anyway, in the interests of others. But we know that this assumption is often untrue! So this feels a bit like having your cake and eating it too.

OSB: What did you find instead?

MBC: Previous experiments couldn't distinguish between an imperfect player and an unselfish player, and they assumed that it was the latter. Our study instead suggests that it is the former.

To do this, we analysed data we had collected previously, from 236 people playing the public goods games. We pitted three different rules that people could potentially use to play the game against each other, to find the one that best fitted the way that people actually played the game. The 'payoff maximizing' rule assumed that people wanted to earn as much money as possible, but they are initially unsure about how to do this. The 'prosocial' rule assumed that people are trying to get the most income for both themselves and the group, while the 'conditional cooperation' rule assumed a sort of 'tit-for-tat' behaviour, with people contributing money only when other players do so.

We found that that the payoff maximizing rule explained our volunteers' behaviour much better than the other rules, and our analyses suggest that what researchers had previously thought were altruistic choices were actually just people learning to play the game.

OSB: Does this mean that the field needs to re-evaluate some widely accepted findings?

MBC: This is potentially quite a bit problem for the field, since all the work (and there is a lot!) using these economic games assumes that you can probe peoples' thoughts, desires and, importantly, preferences by using these games. But if they don't understand the game, it all falls apart. For example, some previous work uses these games to suggest that different people might have varying levels of altruism, with culture and specific genes influencing altruism. But these results could just reflect differences in how well people understand the game, how consistently they play it, whether they use all the information available to them or ignore it, or any combination of these factors.

OSB: How are you planning to explore these ideas further?

MBC: Well, it is interesting to contrast how animal behaviourists and economists study animals making choices. In non-human animal studies, you need a lot of evidence to back up any claims of cognition, and you have to build up any claims for cognitive operations (such as altruism or rational decision-making) from the bottom up. Economics, on the other hand, often assumes that humans always make sensible decisions, and any claims of deviations from this instead need lots of evidence. So it's more of a top-down approach. Scientifically, this doesn’t make any sense: there shouldn't be a difference in approaches to studying humans versus other animals. I am hoping to bring these two approaches together.

More specifically, we’re tackling some of the assumptions behind the idea that there are different types of people when it comes to altruistic behaviour, and what factors promote cooperation amongst people.

We are also interested in looking at the interaction between culture and the spread of social learning.

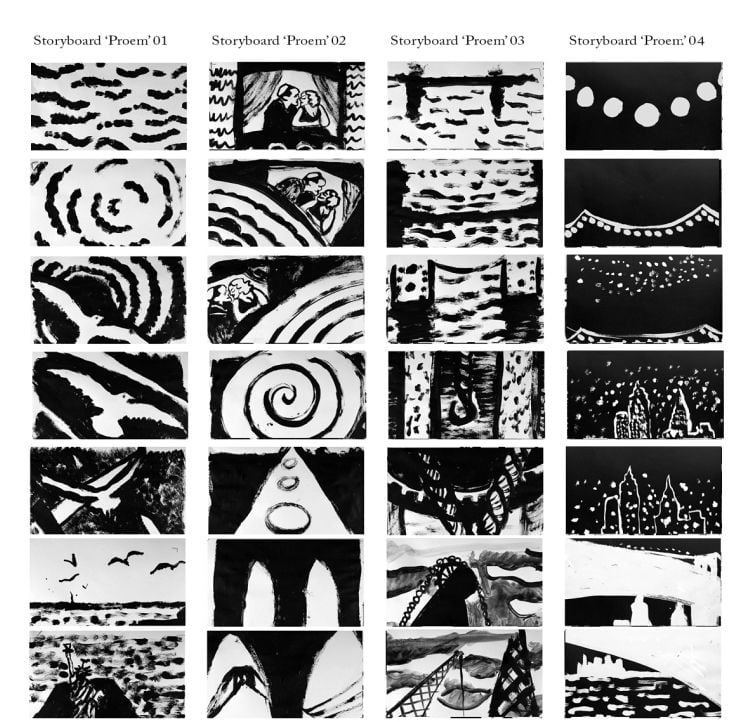

An animated short produced by Oxford researcher Sally Bayley is being screened at film festivals worldwide, including the London Short Films Festival and the Berlin British Shorts Festival. The film, produced by Dr Bayley of the Rothermere American Institute and animated by Professor Suzie Hanna of Norwich University of the Arts, is a stylised representation of a poem by Hart Crane, a 20th century American poet.

'Hart Crane's Proem: To Brooklyn Bridge is the opening to his much longer epic work, The Bridge,' said Dr Bayley. 'His work was a response to poets such as TS Eliot, who wrote about modernity in terms of decline and decay. Crane expresses a more optimistic view of modern life and of the city.'

The animation, produced almost entirely through hand-cut stencils, draws on the bold geometric shapes of 1920s graphic art to evoke the "vertiginous" landscape of New York City. 'For this short film we amassed a huge amount of material: notes, sketches and short test animations,' said Dr Bayley. 'We drew on contemporary influences, including advertising and typography, and art prints by members of Crane’s circle, such as Joseph Stella and Marsden Hartley.'

The soundtrack of the film, composed by Tom Simmons, also draws on Crane’s influences. Crane devised a “shamanic” process for composing poetry, part of which involved listening repeatedly to certain records. Distorted fragments of Ravel’s “Bolero” are incorporated into the sound of the film to evoke this process. The film is being shown at the London Short Films Festival this week.

Proem: To Brooklyn Bridge is the latest in a series of collaborations between Dr Bayley and Professor Hanna, including The Girl Who Would Be God, an animated short inspired by Sylvia Plath’s early drawings, poems and diary entries, which helped to define the collaborative process. 'We were very clear that we wanted the film to be a representation of Sylvia Plath's ideas, rather than a direct portrayal of her. The diary is a kind of self-dramatisation, and even in her teenage diaries Plath begins to play with different ways of exploring and portraying the self,' said Dr Bayley.

The animation - a collage of drawn, painted and photographed images – draws on the same varied cultural background as Proem, alluding to Plath’s musical interests as well as the social and aesthetic world of young women at the time.

Dr Bayley's ongoing research develops the theme of diaries as a tool for self-representation, and she is currently working on a book, The Private Life of the Diary: From Pepys to Tweets.

Notes from the planning of the film

Notes from the planning of the film The storyboard for the film

The storyboard for the filmIn a 3-part of the BBC's science documentary series Horizon, starting tonight on BBC2 at 9 pm, Susan Jebb and Paul Aveyard from Oxford University, together with Giles Yeo and Fiona Gribble from Cambridge, explore whether personalized diets tailored to different causes of overeating can succeed where other diets have failed. 'What I would like people to take away from watching the programme is that rather than jumping on the bandwagon of the latest diet or celebrity endorsement, it is more important to think about the way you live your own life and understand your own triggers, in order to find a diet that works for you', says Susan Jebb, professor of diet and population health at the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford. Oxford Science Blog asked her about her experience with the programme.

OxSciBlog: What are the new ideas being explored in this TV series?

Susan Jebb: Previous discussions about tailoring diets to individual physiology for weight loss have mostly been based on retrospective analyses: by which I mean that it is only after a large study has been done, and a group of people have all gone on a particular diet, there is occasionally some discussion of the characteristics of the people who were more or less successful at losing weight. I cannot think of any studies where researchers have put forward a hypothesis about specific diets being particularly effective for groups of people with a certain trait, and then gone out and tested it. So the TV series gave us a chance to explore a new research direction, though we really need to do more controlled experiments in order to establish any conclusions about personalized diets being more successful than a 'one size fits all' approach.

OSB: What did you get out of working on the programme? Has it changed your day-to-day work?

SJ: It gave me a chance to interact very directly with a large, diverse group of people trying to lose weight. Their stories have directly influenced and shaped some of our research plans: my DPhil student, Jamie Hartman-Boyce, is now working on the self-management of obesity, which we know very little about. Drawing on the experience of the volunteers in the programme, we have developed a questionnaire, the Oxford Food and Activity Behaviours (OxFAB) to elucidate the strategies people use to manage their weight. We would now like to invite lots of other members of the public to get involved too, by clicking through to our website and completing the questionnaire.

People who choose to enrol in the study will be able to track their weight over time and fill in the questionnaires online. The programme participants found that answering the questions helped them to identify new strategies they could try. As time goes on, participants will get feedback on what other people are doing and will be able to compare that to the strategies they are using. Meanwhile, we will be able to build up a picture of the strategies people use and over time to relate the strategies people use to the weight they lose. By understanding strategies associated with success, we hope to be able to develop more effective interventions.

OSB: Who do you hope will watch the programme?

SJ: This programme was also a great way of talking to people such as health professionals and policy-makers. One of my concerns is that within the NHS, we don't necessarily give people a lot of help to lose weight. I am sorry to say that too often, there is still an attitude which says that 'People just need to pull themselves together and eat less'. I hope that this programme might help people begin to recognize that that there are differences between individuals which make it much harder for some people to lose weight than others. Like managing any other chronic condition, people trying to lose weight need our support, not criticism. I hope that raising awareness of the issues that the programme discusses might lead to a more supportive atmosphere for those who want to lose weight.

OSB: How did you get involved in working with Horizon?

SJ: Nutrition is in the media all the time, and I've been involved in media outreach since I was a post-doctoral researcher. I get the same buzz out of media work as I do from academic presentations. In my experience, working with the BBC has been incredibly productive. We have in fact collaborated with Horizon before, and you can almost track the history of scientific developments in obesity through Horizon. I have been in contact with the producers of this programme for almost 2 years now, and indeed, the questions that this programme looks at have developed collaboratively. There was sometimes tension between the competing demands of providing entertainment versus doing science but with discussion, we were able to iron them out. That said, I think it is important to emphasize that the 'experiments' in the programme work as demonstrations of scientific concepts to illustrate aspects of the work. The BBC creative department was really great at bringing these aspects to life and illustrating some of the scientific studies that might otherwise be difficult for a general audience to understand.

I am very passionate about taking the results we get from scientific research and getting it out into society, where it can make a difference to people's lives right now. The media is a fantastic way to do this: far more people will watch this BBC series, compared to the number of people who might be expected to come to a public lecture in Oxford.

OSB: What were the best and worse things about working on a prime-time television programme?

SJ: The best thing for this series was working alongside some of my colleagues and seeing them doing things that I would never have imagined they would do: Giles Yeo (at Cambridge) clad in gauntlets in a meat freezer, wielding an enormous knife, and Paul Aveyard (Professor of Behavioural Medicine at Oxford) in a scene reminiscent of the Great British Bakeoff, talking about an unplanned cake eating incident'.

The worse thing about television is that it is SO time-consuming and so much ends up on the cutting room floor. On one occasion, I spent 5 hours sitting around in a field, and about fifty words have made it on screen.

OSB: What advice would you give to someone thinking of being involved in television?

SJ: First, I would absolutely say do it: I think it presents amazing opportunities to make science part of everyday conversation. But here are some things to keep in mind:

- Choose your programme and production team very carefully. In dieting and nutrition, there are some very exploitative programmes around which I would not be comfortable being linked to. So do your groundwork.

- Don’t ever compromise your scientific and moral principles. Yes, you need to simplify, but it is important that you never get yourself into a position where you are saying something that you wouldn’t be prepared to defend later.

- Relax – it may not be perfect but how many scientific papers do you look back on and feel they were perfect? And like an academic presentation or a grant application, it gets easier over time and hopefully you get better with practice.

Professor Susan Jebb is the speaker for the 2015 Oxford London lecture on 17th March, 2015. The lecture is open to the public, and will discuss how to improve the nation’s diet.

The winner of the first Oxford/Sennheiser Electronic Music Prize (OSEMP) can be heard here.

Launched last year, the competition received more than 100 entries. Ten finalists were chosen to perform their composition in front of a live audience and a judging panel of leading electroacoustic composers Natasha Barrett and Trevor Wishart and Oxford University's Professor of Composition Martyn Harry.

The judges chose Samuel Barnes' composition The Nature in Devices as the winner. Sam Kendall's One Fast Move or I'm Gone and Daniel Cioccoloni's Deep Time came second and third respectively.

Samuel responded to his win on Twitter, saying: 'Delighted, shocked and honoured to have been awarded first place at OSEMP. A wonderful evening of inspiring new music!'

Eric Clarke, Heather Professor of Music at Oxford's Faculty of Music, said: 'OSEMP attracted a huge field of entries, ten outstanding finalists and three extremely talented winners. In many ways, though, it was the audience in the packed Jacqueline du Pré music building who were the real winners. They were fortunate to be present at a memorable evening of terrific music. We’re already looking forward to next year!'

OSEMP was sponsored by audio specialists Sennheiser, which has also supported the Oxford Surround Composition and Research studio at (OSCaR) - a bespoke, state-of-the-art electronic music studio which opened in the University last year. The competition, which was also supported by Warp Records, aimed to find the most innovative new works in electronic music by composers aged 35 and under.

The Oxford Slade Lectures 2015 will be on the subject of printmaking before photography, it has been announced.

Antony Griffiths, former Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, will give eight lectures under the title, ‘The print before photography: The European print in the age of the copper plate and wooden block'.

The lectures will be held every Wednesday at 5pm between 21 January and 11 March at the Mathematic Institute on the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter. The lectures are open to the public and admission is free.

The Slade Lectures were founded in 1869 after a bequest from the art collector Felix Slade in 1869. John Ruskin gave the first series of eight public lectures in 1870. In his inaugural lecture he announced that he was setting up the Ruskin School of Drawing, which is now the Ruskin School of Art.

Professor Griffiths said: 'Gutenberg's invention of moveable type made it possible to print letters. But images could only be printed using two other technologies that were developed alongside letterpress. One depended on wooden blocks which were cut and printed in relief, the other on copper plates into which lines were cut by engraving or etching and were printed on a rolling press.

'Copper-plate printmaking developed into a huge business employing thousands of people, and dominated image production for nearly four centuries across the whole of Europe. Its processes remained very stable, and a man of 1500 could have walked into a printing shop of 1800 and understood what was going on. During the nineteenth century this world was displaced by new technologies, of which photography was by far the most important.'

He added: 'Today the old hand-crafted processes that used wooden blocks and copper plates are obsolete, and are only found in the small area of printmaking by artists. The Slade lectures will attempt to resurrect this lost world and describe its structure.'

Craig Clunas, Professor of the History of Art at Oxford University, said: 'These free lectures are designed to be accessible to non-specialists, and I think anyone interested in the visual arts will get great insight and enjoyment from them. Antony has an extremely distinguished record as head of the British Museum's Prints and Drawings Department for many years, and as the author of some two dozen books and exhibition catalogues on the subject.'

More information on the lectures can be found here.

- ‹ previous

- 156 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?