Features

As reported by the BBC, scientists at Oxford University have built a mathematical model to explain the secrets of the chameleon's extraordinarily powerful tongue.

The chameleon's tongue is said to unravel at the sort of speed that would see a car go from 0-60 mph in one hundredth of a second – and it can extend up to 2.5 body lengths when catching insects.

A team from Oxford's Mathematical Institute (working in collaboration with Tufts University in the US) derived a system of differential equations to capture the mechanics of the energy build-up and 'extreme acceleration' of the reptile's tongue.

The research is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A.

Derek Moulton, Associate Professor of Mathematical Biology at Oxford and one of the authors of the paper, said: 'If you are looking at the equations they might look complex, but at the heart of all of this is Newton's Second Law – the sort of thing that kids are learning in A-levels, which is simply that you're balancing forces with accelerations.

'In mathematical terms, what we've done is used the theory of non-linear elasticity to describe the energy in the various tongue layers and then passed that potential energy to a model of kinetic energy for the tongue dynamics.'

Special collagenous tissue within the chameleon's tongue is one of the secrets behind its effectiveness. This tissue surrounds a bone at the core of the tongue and is surrounded itself by a muscle.

Professor Moulton added: 'The muscle – the outermost layer – contracts to set the whole thing in motion. We've modelled the mechanics of the whole process; the build-up and release of energy.'

The researchers say the insights will be useful in biomimetics – copying from nature in engineering and design.

Previously, Science Blog has reported on the work of Dr Lingbing Kong in Oxford University's Department of Chemistry, who is exploring new methods of antibacterial vaccination that could combat the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

In a new paper published in Nature Chemistry, Dr Kong takes an in-depth look at capsular polysaccharides, or 'sugar armour' – the outermost layer of bacteria that provides a key defensive shield for pathogens (including against antibiotics).

Here, Dr Kong describes the latest research:

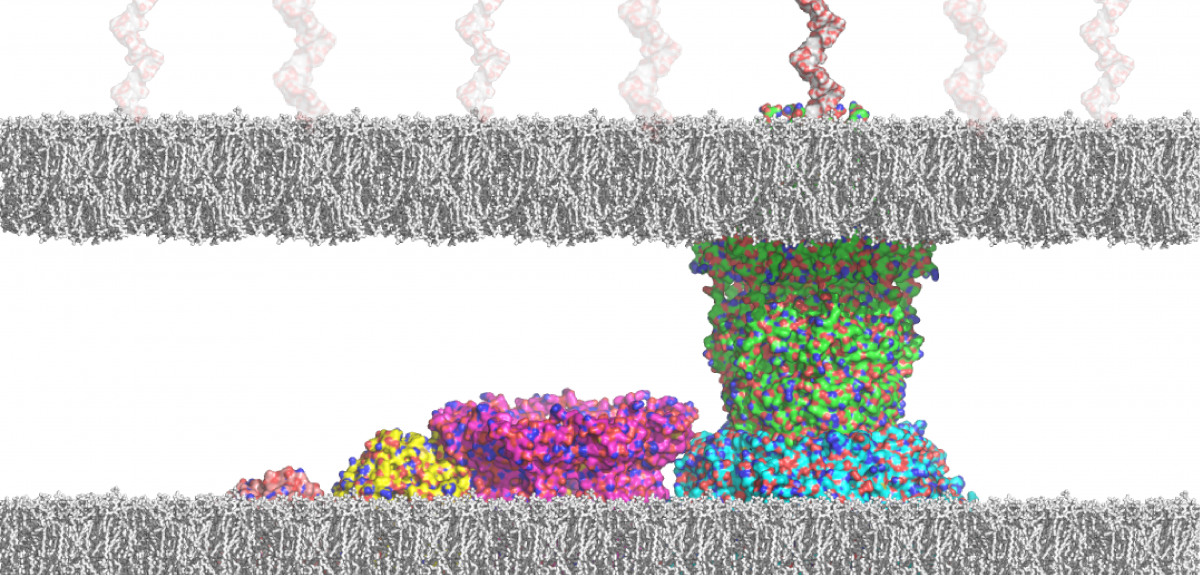

'I started the work contained in the paper in 2007 in the labs of Professor Ben Davis and Professor Hagan Bayley in Oxford's Department of Chemistry. The overall aim of my project was to elucidate the interaction of the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) K30 and its exporter outer membrane protein Wza, which would facilitate the development of novel antibacterial strategies. The biochemical, biophysical, and biological part of the project was going smoothly and led to the discovery of the first inhibitor of the Wza pore. It is, however, fundamentally important to analyse the interaction of the K30 CPS and the Wza pore at the single-molecule level, which would be crucial for later generations of the Wza inhibitor when resistant mutants appear.

'This part of the project had several barriers that had to be overcome – it has been a great challenge in academia to successfully analyse this kind of bimolecular interaction. The carbohydrate-protein interactions are generally weak, and the access to defined oligosaccharides and polysaccharides is always the main limiting factor. Therefore, we dedicated ourselves to achieving this goal.

'This new Nature Chemistry paper reports how we achieved this over the last nine years and reveals new insights into the important biological process.

'We have developed a generalised synthetic approach to obtain polysaccharides with defined sizes, which has rarely been attempted in literature. In polysaccharide-related syntheses, it has been a frequent bias that only one of the possible repeating ("monomer") units, typically the most synthetically accessible, is selected for synthesis. Our approach includes a non-biased analysis of the targeted polysaccharide for all possible minimum oligosaccharide repeating units. Next, multi-step organic synthesis gave the desired repeating units, which were then activated to form the according oligomers and polymers.

'Further separation by high-performance liquid chromatography afforded the defined large oligosaccharides and polysaccharides in pure forms. The analysis of the interaction between K30 carbohydrate fragments and the exporter Wza pore was carried out with an advanced droplet system that requires a volume as small as 200 nanolitres. This setup was developed to enable analysis and detection of the behaviours of the same protein pore before and after the addition of the sugar substrates, which was not possible previously. As a result, the weak interaction between K30 CPS and the Wza pores was detected at the single-molecule level.

'Analysis of the complex data revealed that only small (not large) fragments of the K30 fragments were translocated through the pore. We also observed capture events that occur only on the intracellular side of Wza, which would complement coordinated feeding by adjunct biosynthetic machinery.

'The techniques that we developed to recapitulate sugar export at the single-molecule level would potentially allow studies of all bacterial sugar export. This will facilitate not only the detection of the sugar-exporter interactions but also screening of blockers of the sugar exporters. In addition, the generalised approach that we developed for polysaccharide synthesis, ie polyglycosylation, could potentially be applied to all polysaccharide synthesis. Such approaches are rarely reported and usually not generalisable.

'Our approaches exemplified: 1) non-biased analysis of the chemical structures of the target polysaccharide; 2) rational design and solid synthesis of all polymerisable minimum oligosaccharide repeating units; 3) screening and optimization of conditions for polyglycosylation; and eventually 4) separation of individual oligomeric and polymeric products, which is followed by deprotection to afford defined and pure large oligosaccharides and polysaccharides.

'On the other hand, the advanced droplet system that we developed enables the detection and analysis of weak interactions between a membrane protein pore and the substrates in a very small quantity at the single-molecule level. For one single experiment, only one protein pore and 1 microgram (or even 1 nanogram) of substrate (given molecular weight 500 and a concentration of 1 minimole/litre or 1 micromole/litre, respectively) are required.

'Nowadays, mass spectrometry is one of the most sensitive techniques. The technology we developed would enable the detection and analysis of bimolecular interactions in the same resolution. We therefore expect our technologies to find far-reaching applications in numerous vital binding processes in glycobiology.'

If you're seeking to understand mental ill health, it helps to understand mental health first. This is particularly true of neuropsychiatric conditions – when problems with the structure or function of the brain underlie diagnosis. Simply put: If we know what a healthy brain looks like and how a healthy brain works, we can better understand how to diagnose and treat neuropsychiatric conditions.

We have shown that reducing cortical inhibition can unmask silent memories. This result is consistent with a balancing mechanism – the increase in excitation seen in learning and memory formation, when excitatory connections are strengthened, appears to be balanced out by a strengthening of inhibitory connections.

Dr Helen Barron, Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) and MRC Brain Dynamics Unit

One key question about healthy brain function concerns the interaction between two types of cells in the brain – excitatory and inhibitory neurons. The former increase activity in a given area of the brain, while the latter decrease activity. Yet, when scientists measure the voltage – called conductance – received by a given cell, they find that excitation and inhibition are balanced, maintaining a stable state in the neuron.

Various scientists have hypothesised that when excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance is disrupted, this results in neuropsychiatric conditions like schizophrenia and autism. A more obvious example of such imbalance is epilepsy – where run-away excitation can be observed.

So is a healthy mind literally a well-balanced mind? And if so, how does the brain keep this balance in check?

Dr Helen Barron is a research fellow of Merton College at the University of Oxford, based jointly at the Medical Research Council Brain Dynamics Unit and the Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB). In a paper published this week, she and her colleagues shed light on how E/I balance is maintained in the healthy brain.

One thing to realise, she explains, is that a healthy brain is not always in a state of perfect balance. In the cortex, during learning and memory formation, connections between excitatory cells are strengthened, causing an E/I imbalance. Yet, balance must eventually be restored. Looking at theoretical work and the results of recent experiments in rodents, she hypothesised that the increase in brain activity due to strengthened excitatory connections becomes balanced out by corresponding changes in the strength of inhibitory connections. These restorative inhibitory connections can be considered inhibitory replicas of memories, and may therefore be described as 'antimemories'.

The issue now was to find a way to test the hypothesis in the human brain. One difficulty with studying the human brain is that there is no way to easily measure what is happening in individual cells. Instead, available techniques tend to give a larger-scale representation of what is happening in an area of the brain.

FMRIB, at the University of Oxford, has a powerful MRI machine with magnets of 7 Tesla strength which allowed the team to get a more detailed picture of brain activity. To put that in context – 1 Tesla is about 20,000 times the strength of Earth’s magnetic field and medical MRI scanners are usually 1.5 Tesla . Even so, to get the level of detail they wanted, Helen and her colleagues took the unusual step of combining a number of techniques with functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, including magnetic resonance spectroscopy, transcranial direct current stimulation and computer modelling.

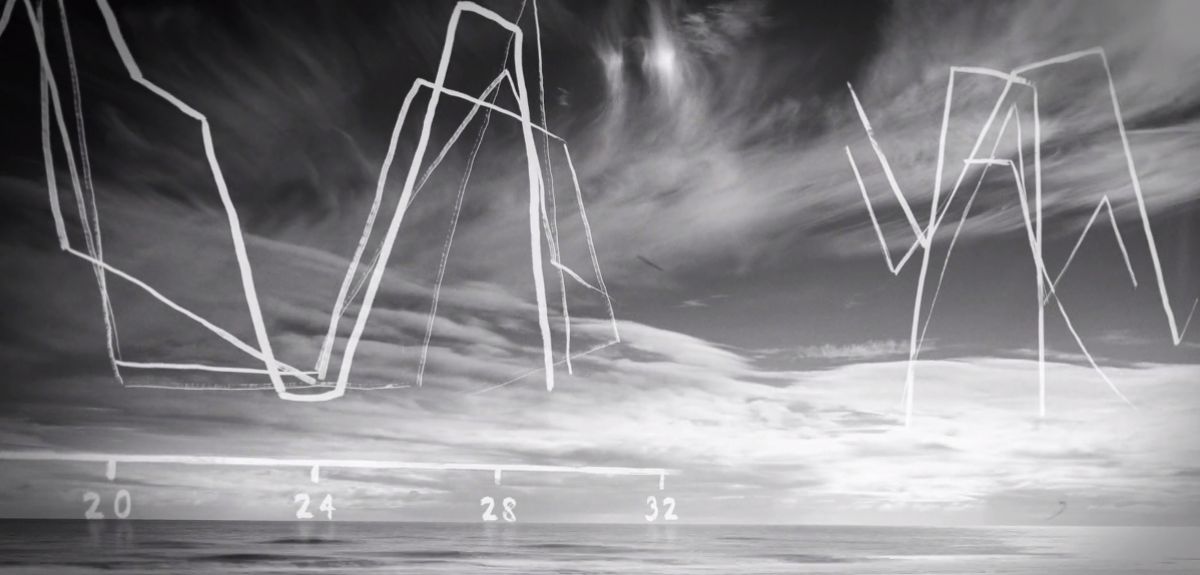

Dr Barron explained the process: 'Volunteers were taught pairs of shapes. If you link shape A with shape B, we will see brain activity related to shape A followed by brain activity related to shape B. To measure these links, or associative memories, we use a technique called repetition suppression where repeated exposure to a stimulus – the shapes in this case – causes decreasing activity in the area of the brain that represents shapes. By looking at these suppression effects across different stimuli we can use this approach to identify where memories are stored.

'Over 24 hours, the shape associations in the brain became silent. That could have been because the brain was rebalanced or it could simply be that the associations were forgotten. So the following day, some of the volunteers undertook additional tests to confirm that the silencing was a consequence of rebalancing. If the memories were present but silenced by inhibitory replicas, we thought that it should be possible to re-express the memories by suppressing inhibitory activity.'

The team therefore used transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), where a safe, very low current is passed across the brain to modulate inhibitory activity. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy allowed them to measure the concentration of certain neurochemicals linked to excitation and inhibition, including GABA, which is linked to inhibition. If the concentration of GABA reduces, inhibitory activity also reduces. So if their theory was correct, this reduction in GABA should reduce the silencing effect of inhibitory connections upon memories.

That's exactly what happened: When tDCS was applied, memories of the shape associations were re-expressed. Notably, those volunteers who showed the greatest reduction in GABA concentration were also those with the strongest re-expression of the memory.

Helen explains: 'We have shown that reducing cortical inhibition can unmask silent memories. This result is consistent with a balancing mechanism – the increase in excitation seen in learning and memory formation, when excitatory connections are strengthened, appears to be balanced out by a strengthening of inhibitory connections. From this we can infer that memories are stored in balanced E/I cortical ensembles.'

The results are also important because they have shown how it is possible to get information about the workings of the brain at a more detailed level than previously possible.

While the human part of the study has provided a better understanding of balance in a healthy brain, there was a further piece of work that has added to the team’s conclusions.

Having a set of tools that can be translated into clinical use will enable psychiatrists to identify more easily when processes demonstrate unhealthy activity.

Dr Helen Barron, Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) and MRC Brain Dynamics Unit

They worked with computational neuroscientist Dr Tim Vogels who used an artificial neural network to simulate the same processes demonstrated in the volunteers. This provided a qualitative description of the same result and was able to show how the signals observed in the human brain may arise from changes in the strength of neural connections.

Helen concludes: 'The paradigm has the potential to be translated directly into patient populations, including those suffering from schizophrenia and autism. We hope that this research can now be taken forward in collaboration with psychiatrists and patient populations so that we can develop and apply this new understanding to the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders.'

She, meanwhile, will continue to index the healthy brain, providing the important reference points for further research into mental illness: 'I am trying to find indexes for microscopic processes in the human brain. Having a set of tools that can be translated into clinical use will enable psychiatrists to identify more easily when processes demonstrate unhealthy activity.'

What do you get when you cross an artist with a scientist?

It's not a trick question, but the basis of a project called Silent Signal, which brought together six animation artists and six leading biomedical scientists, to create experimental animated artworks exploring new ways of thinking about the human body.

Oxford University's Professor Peter Oliver worked with artist Ellie Land, talking about the links now being discovered between sleep and mental health. The result is a five minute animation titled Sleepless. Its rhythm is inspired by the circadian cycle and displays visual icons rooted in the science of sleep, whilst featuring the voices of a group of mental health service users who share their experience of disrupted sleep/wake patterns.

That disruption is the target of Peter’s research. He studies gene function in the brain and the consequences of gene dysfunction in disease, with focus on the relationship between sleep and mental health.

Watch the animation below or find out more at: http://www.silentsignal.org/Collaborations/sleepless/

Scientists have long known that our bodies need to control the communities of bacteria in the gut to prevent a beneficial environment from turning into a dangerous one. What hasn't been known is how we do this.

Now, Oxford University researchers have proposed a clever solution to the problem: make good bacteria sticky so they don't get lost. The key to this is for a host to target good bacteria over bad ones – potentially via the immune system, which produces highly-specific adhesive molecules called immunoglobulins (specifically 'IgA') that coat the bacteria in the gut.

The research is published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

Co-lead author Kirstie McLoughlin, of the Department of Zoology at Oxford University, said: 'We carry with us vast communities of bacteria that live on us and inside us, particularly in our intestines. These bacteria perform many functions for us, such as breaking down our food, helping our immune system develop, and protecting us from pathogenic bacteria. These are what are often known as the "good" bacteria: a diverse set of beneficial species that improve our health and wellbeing.'

These bacteria perform many important functions for us, and if the wrong species take hold inside us the results can be dramatic. An upset stomach is a common result of a pathogen such as Salmonella taking hold, but there are also many other effects of having undesirable bacterial species in the gut. These include chronic inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, and an increased risk of conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. There has also been some suggestion that the microbiota contributes to some psychological disorders.

Discussing the latest study, co-lead author Jonas Schluter of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center – who has carried out previous work on the 'stickiness' of bacteria – said: 'Our gut is lined with our own epithelial cells, and we use these to secrete all kinds of compounds into the gut. That is, we don't just absorb nutrients from our gut, we release a lot of things back in. This includes mucus, which can be modified so that it sticks to particular bacteria and also antibodies – one of the key tools of the immune system.

'In particular, a class of antibody called IgA (immunoglobulin A) is released into the gut in large quantities. This is a sticky molecule that comes in a vast number of forms where each one can preferentially target a particular strain or species of bacteria. By using things like mucus and IgA, therefore, humans have the ability to make certain bacteria sticky. We are proposing that this can be used to hold them close to the epithelial surface in the gut.'

Senior author Professor Kevin Foster of Oxford University added: 'Our study is based on a computational model of the gut and the key next step is a direct empirical test of our idea. However, as we discuss in our study, existing data do support our idea that stickiness may be a simple and powerful way to control the bacteria that we carry with us.'

- ‹ previous

- 128 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools