Features

You're in hospital and you need to have a blood test: What do you think would reduce your pain?

- Sucrose (sugar water)

- Painkillers

You probably went with option 2. But in babies option 1 is often prescribed.

Ultimately, we would like to provide better pain relief for some of the most vulnerable patients in hospital.

Prof Rebeccah Slater, Department of Paediatrics

It is difficult to test whether painkillers work for very young children and we often don't know the best dose to give. But if Professor Rebeccah Slater and her research team at Oxford are successful we may find alternative ways to measure pain in babies and may eventually be able to offer babies some better options to soothe their pain.

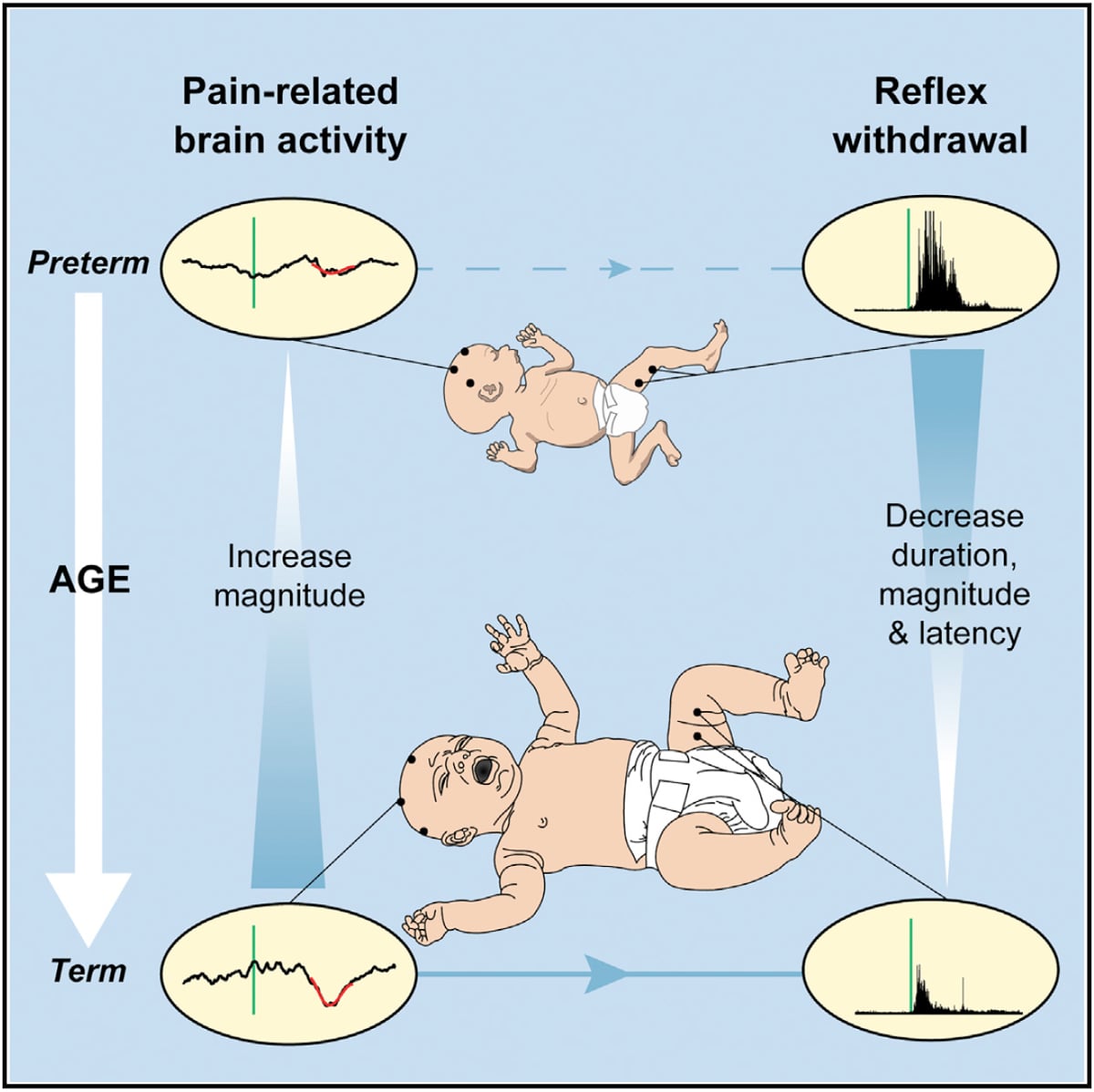

Their latest research, published in Current Biology and led by Caroline Hartley and Fiona Moultrie, looks at how babies who have been born early respond when a blood sample is taken from the heel of their foot.

Premature babies have to undergo various procedures, including regular blood tests. So, with the support of parents and working with the charity SSNAP, babies were recruited to the study and the team were able to measure both brain activity and reflex responses during this painful procedure.

Dr Hartley said: 'The youngest babies have disorganised and exaggerated motor responses when painful procedures are performed. For example, they might pull away both feet even when the blood test is performed on just one foot.

'As they get older, these reflex movements become quicker, shorter and smaller. They respond faster but don't pull away as much. However, you cannot directly infer how much pain a baby is experiencing from these responses – for example a premature baby can withdraw both their legs even in response to a light touch.

In the study the babies' brain activity was also measured by placing electrodes on their heads prior to the blood tests – this technique is called EEG (electroencephalography).

Dr Hartley said: 'The younger babies showed brain activity that was not specific to pain – a bright light or loud noise would cause much the same pattern of activity. As they got older, brain activity matured and the evoked brain activity increased.

'Considering both measures together, we found that older babies with more mature brain activity had more refined reflexes. '

This study suggests that top-down inhibitory mechanisms may begin to emerge during early infancy. As adults, we may instinctively stop ourselves from pulling our hand away from the handle of a hot pan if the alternative would be to tip boiling water everywhere, a potentially more dangerous result: that's an example of top down inhibition. The observation that, as the babies get older, more mature brain activity is related to more refined reflex activity, suggests that these inhibitory mechanisms may begin to play a role.

Pains, brains and clinical trials

Professor Slater explained the context of the research: 'Previous research in animals, which has been pioneered by colleagues at UCL, has shown that top-down inhibitory mechanisms develop in early life. Our results suggest that this research can be translated into humans.

'The results are also relevant to medical practice: doctors and nurses rely on behavioural observation to make judgements about pain in babies. Our results show that the movements of a premature baby in response to a painful procedure may not be proportionate to the amount of information that is being transmitted to the brain.

'That is also critical if we are trying to develop effective pain relief for babies. If we understand better how the immature brain processes information about pain, we may be able to use these patterns of brain activity to see whether different types of pain relief are effective in babies.'

Her next study, starting in September 2016 will test that. The team will measure brain activity and reflex withdrawal activity in a randomised controlled trial investigating whether morphine provides effective pain relief during clinically essential medical procedures.

Professor Slater said: 'Ultimately, we would like to provide better pain relief for some of the most vulnerable patients in hospital.'

We know a lot about JRR Tolkien's writings and his biography.

But what was the creator of Middle Earth like when he was being ordered around for a documentary?

An Oxford academic has found the answer while researching for a BBC Radio 4 documentary.

The documentary, which was broadcast on Saturday, follows the search by Dr Stuart Lee, an English academic and an expert on JRR Tolkien, to find an unbroadcast interview with Tolkien which was shot as part of a documentary on the Lord of the Rings author in 1968.

In the BBC archives, Dr Lee found 90 minutes of unbroadcast interview with Tolkien that was filmed in addition to the seven minutes used in the original documentary.

While making the programme, Dr Lee brought together the original documentary-maker Lesley Megahey, and three stars of the documentary: researcher Patrick O’Sullivan, Tolkien fan Michael Hebbert, and critic Valentine Cunningham.

Over a pint in Tolkien’s favourite pub, the Eagle and Child, Dr Stuart Lee explains what this video tells us about the author.

Oxford University researchers work with partners around the globe to develop new treatments to benefit people worldwide. Sometimes, those relationships enable our scientists, many of whom are also practising doctors, to benefit individuals too, as Kimberley Bryon-Dodd explains.

July 28 is World Hepatitis Day. More than 300,000 people in the United Kingdom are known to be infected with Hepatitis C virus. Although in some cases it can be a relatively mild infection and patients eventually eradicate the virus after a couple of weeks, it can also be a lifelong condition causing severe liver damage that requires a transplant and that can ultimately result in death.

Knowing that you're dying if nothing happens is very different to knowing that you will die soon.

Nils Nordal

In 2014 Nils Nordal was on the brink of death due to liver failure. After contracting the disease during dental treatment in Egypt 20 years ago he desperately needed a liver transplant to survive. However, the hepatitis virus would attack any new liver so he urgently needed treatment before surgery to clear the virus from his bloodstream.

In an impossible situation, his body was so weak that the standard treatment to clear the virus (interferon) would likely kill him. Each week ten litres of excess fluid needed to be drained from his abdomen in an excruciatingly painful procedure, and he was bent over, unable to pick up his young children or walk without a cane.

'Everything that could go wrong with the liver had gone wrong with my liver. It was massively sclerotic. I had varices, I had ascites. It wasn't in good shape and it was pretty clear that I needed a liver transplant. '

There was one option. Sofosbuvir, a uridine nucleotide analogue that inhibits hepatitis C virus polymerase to prevent the virus replicating, had been shown to be incredibly effective in the USA and had just been approved in Europe for treatment of Hepatitis C. NHS England were in the process of setting up the Early Access scheme scheme where patients, such as Nils, with advanced liver disease would receive these new drugs but it was in the early stages so the medication was not available to Nils.

'My baseline viral load was 494,000 copies of the virus per ml of blood'

Professor Ellie Barnes, Nils' consultant, was convinced that Sofosbuvir would eradicate the Hepatitis C virus from Nils' body and with his condition quickly deteriorating, she went directly to the maker, Gilead Sciences, to get it. Nils became one of the first people in the UK to receive Sofosbuvir outside a clinical trial.

'I started the course in May 2014. My baseline viral load was 494,000 copies of the virus per ml of blood. After I had been on Sofosbuvir for one week it was down to 64 copies per ml of blood. By week 2 it was down to 16 and by weeks 3 and 4 the virus was almost undetectable at between 0-15 copies per ml of blood. By week 5 amazingly the virus was no longer present.'

After eradicating the virus Nils was finally able to go on the transplant list for a new liver. In August 2014 he saw his consultant in London and was told to spend as much time as he could with his children as he had at the best 6 months to live without a new liver. Nils was diagnosed with advanced liver disease and was starving to death due to an inability to process food to get any nourishment.

'Vampire in a casino'

'Knowing that you're dying if nothing happens is very different to knowing that you will die soon.

'When you get a transplant your new liver has to match your blood type and body size. It is a weird situation where you are like a vampire in a casino. You are waiting for your number to come up so that you can feed. Which means that somebody else is dead. It is an awful thing but you are praying for the right person to die.

'I was the back-up person for a liver as they thought the person in front of me would not survive the operation. There is nothing worse than sitting in a hospital waiting to find out if you will live or die that day.'

Thankfully, Nils was able to receive a transplant in time and has now mostly recovered.

As part of the Oxford Hepatology Research Team led by Dr Jane Collier and Professor Barnes we had experience of working with Gilead Sciences in the Phase III clinical trials with these new Direct Acting Anti-Virals, Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir (now licensed as Harvoni) and we had treated patients with this drug in a clinical trial setting. I believe all of this had led to us having a good working relationship with Gilead which I think helped in pushing for Nils to receive Harvoni.

Denise O’Donnell, Senior Hepatology Research Nurse

'In the ICU I was afloat in a sea of tubes. I had tubes in and out of my neck and my arms. I had drains in both sides of my abdomen to get rid of excess liquid. I had oxygen going down my nose and throat. It was me, excruciating pain, a solitary nurse, and a bunch of machines; but I was alive.

'I had an amazing recovery. The first step is just getting out of the bed and moving to a chair. I was out of ICU after 2 days and walking after a week. I woke up every morning with the sunrise because it was so amazing to be alive. 3 weeks after surgery I was able to be in the park with my kids. I was driven there but I could pick my daughter up for the first time in 6 months.

'I am alive because of the liver transplant but I have survived because of the treatment, Sofosbuvir. It is the most amazing drug and I completely credit it with my being alive. The joy of being alive and take care of my family is the best job I have ever had.

'I am tremendously grateful to everybody who contributed keeping me alive.'

Today, the hepatitis treatment service run by Dr Jane Collier is available in regions across the UK and has enabled relatively equitable access to drugs across England.

One challenge now faced by University researchers is to identify patients who are unaware that they are infected with Hepatitis C and to develop and provide a vaccine to prevent new cases.

When it comes to your bone health, the benefits of alendronate outweigh the risks, Associate Professor Daniel Prieto-Alhambra from the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences tells Jo Silva

As an Associate Specialist in Metabolic Bone, I welcome strong evidence-based guidance on the safety of medication I'm likely to prescribe to my patients. As a clinical researcher, sometimes I get to answer my own questions.

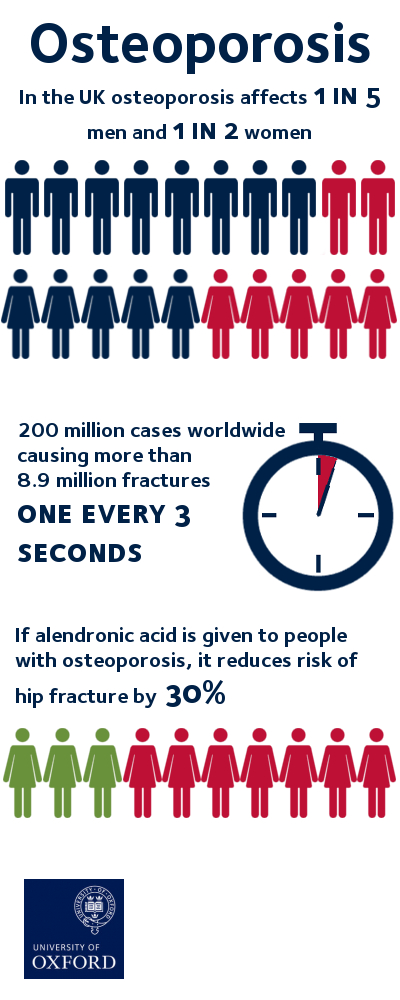

Worldwide, osteoporosis affects more than 200 million people and causes more than 8.9 million fractures annually, resulting in an osteoporotic fracture every 3 seconds.

In the UK, 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men over 50 will suffer a fracture related to osteoporosis, making it a much more common condition than other diseases which usually catch public attention, like breast or prostate cancer.

Currently, alendronate – a bisphosphonate drug – is one of the most common medications for osteoporosis, but prescription rates have declined by 50% in both the US and the EU amid fears of its potential risks of it leading to more (the so-called atypical) fractures.

This was bad news for osteoporosis patients. With it being the first line therapy, it was crucial to investigate the effects of taking alendronate for a long time. This can inform doctors and support patients to understand their treatment and options.

By using the Danish prescription registry, we are closer to an answer on the benefit/risk cost of alendronate. Holding almost 20 years of drug exposure data for all residents in the country, the registry can also be linked to all fractures treated in hospital in the same period.

The results of our study into alendronate using the Danish registry were recently published in the BMJ and suggest that taking this medication for over 10 years is associated with a reduced risk of hip fracture by 30% whilst not increasing other femoral fractures overall – both are excellent news to patients worldwide, as well as doctors tasked with prescribing suitable medication for their patients, like me.

How we did our study

We used anonymised records on hospital contacts and drug dispensations in the whole of Denmark.

From there, we identified all users of alendronate, and we followed them for as long as available (more than 10 years for some) until they fractured their hip or other parts of their femur. We then matched these fracture cases to non-fractured alendronate users to then study the association between drug use - long versus short-term use, and high versus low compliance - and fracture risk.

What's next?

The main limitation of our study is its observational nature, meaning that patients were not randomly allocated to treatment but prescribed treatments based on clinical recommendations.

In addition, there are other potential side effects like osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) that need quantification within the same cohort. We are now therefore working on an analysis of the risk of ONJ in this same population, which we hope to report upon in the coming few months.

It has been the farthest planet from the Sun since Pluto's 'relegation', but despite Neptune's remoteness in our solar system, it still holds plenty of interest for physicists – not least because of the unusual things going on in its atmosphere.

A new paper published in the journal Nature Communications by Dr Karen Aplin of Oxford University's Department of Physics attempts to get to the bottom of the 'wobbles' observed in Neptune's atmosphere over the past 40 years.

The study, written with Professor Giles Harrison of the University of Reading, evaluates two competing hypotheses for why we can see changes in the planet's brightness – a phenomenon essentially connected to its cloud cover. The results solve a long-standing conundrum in planetary science.

Dr Aplin says: 'Neptune's great distance from the Sun means that its atmosphere is very cold, but despite this it has some interesting weather, including clouds, winds, storms and perhaps lightning. It provides an entirely different environment to help us test our knowledge of atmospheres.

'Unlike Earth's atmosphere, which is mostly nitrogen, Neptune's atmosphere is mainly hydrogen and helium, with some methane. The methane absorbs much of the red light in the atmosphere, making the planet seem blue to us.

'Neptune’s atmosphere contains clouds made of a range of substances, such as ammonia and methane, whereas clouds on Earth are almost always made of water. Neptune's atmosphere is also a lot colder than ours – around -170C – because it receives 900 times less sunlight. Despite this, the Sun can still affect its clouds in subtle ways.'

Since the early 1970s, Neptune's brightness has been measured with great care by Dr Wes Lockwood of Lowell Observatory in Arizona. Because Neptune rotates around the Sun once every 165 years, each of its seasons is about 40 Earth years. Most of the ups and downs seen in Neptune's brightness since the 1970s are therefore due to its slowly changing seasons. However, even when the seasonal changes are accounted for, there are still some other small 'wobbles' in Neptune's clouds – and these are the subject of Dr Aplin's study.

Dr Aplin says: 'The "wobbles" in Neptune's cloudiness appeared to follow the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle, which could mean that they were influenced by small changes in sunlight. Another suggestion was that particles from outer space, called cosmic rays, which are also affected by the solar cycle, were changing the clouds. Using the different physics of the two mechanisms, we showed that the combined effect of the two "rival" hypotheses explained the changes in cloudiness more successfully than each would do individually.

'We also looked for a known marker of cosmic ray effects, a kind of fingerprint, in Neptune's cloud data. During the 1980s, when the Voyager 2 mission was nearing Neptune, we were able to compare both cosmic rays and clouds at Neptune and show that they had the same fingerprint. We were therefore able to confirm the effects of cosmic rays in planetary atmospheres.'

Another mission to Neptune would allow for even more scientific insight into this distant planet. But, with nothing currently planned, scientists will continue to rely on telescopic observations combined with simulation experiments of the type carried out in Dr Aplin's laboratory.

- ‹ previous

- 121 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools