Features

Miguel Pereira Santaella, Research Associate at the Oxford University Department of Physics, discusses his newly published work observing never before seen water transitions in space. He breaks down how the discovery will help scientists to answer big planetary questions and build a more accurate understanding of the universe.

From clouds to rivers, and glaciers to oceans, water is everywhere on Earth. What’s less well-known, though, is how abundant the molecule is in space.

Unlike on Earth, most of the water in space takes either the form of vapour or forms ice mantles stuck to interstellar dust grains. This is because the extremely low density of interstellar space - which is trillions of times lower than air, prevents the formation of liquid water. the birth of star formations can tell us about how the Universe behaves. But, since the only way to study them in such dust obscured environments is through the infrared light, detecting water transitions capable of detecting this light, is of vital importance.

Observing the birth of star formations can tell us a great deal about how the Universe behaves. But, since the only way to study these events in such dust obscured environments is through the infrared light, detecting water transitions capable of capturing this light, is vital.

Water molecules experience fluctuating quantum energy levels. This activity allows us to observe them and is known as a water transition. The term refers to the best point for scientific observation, which is the exact wavelength at which water molecules go from one quantum state to another, emitting light and increasing their visibility as they do so.

The majority of these transitions are not very energetic so they appear in the far-infrared and sub-millimetre ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum, with tiny wavelengths (ranging from 50 μm and 1000 μm (1 mm)). Observing these water transitions from the ground is very difficult because the thick vapour in Earth’s atmosphere almost completely blocks the emission from view.

Improvements in technology and the development of super telescopes offer an increasing gateway to the universe, and planetary insights are moving at rapid pace. We can now detect water transitions in ways that we just could not before. They are best seen from telescopic observatories situated at high-altitude, in extremely dry sites. Such as, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), which is located in the Atacama desert (Chile) at 5000 m above sea level.

Image of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), showing the telescope’s antennas under a breathtaking starry night sky. Image credit: Christoph Malin

Image of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), showing the telescope’s antennas under a breathtaking starry night sky. Image credit: Christoph MalinIn our study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, we used ALMA and detected the (670 μm) water transition in space, for the first time. The molecules were spotted in a nearby spiral galaxy (160 million light years away) at a point where the Universe is vastly expanded, and the atmosphere is therefore at its most transparent (red-shifted at 676 μm).

The water vapour emission in this galaxy originates at its core, in its nucleus, where most star formation takes place. To give you an idea of how enormous this galaxy is, the nucleus contains an equivalent amount of water 30 trillion times that of Earth’s oceans combined, and has a diameter 15 million times the distance from Earth to the Sun.

So what sets this water transition apart from others observed in the past? Our analysis revealed that these water molecules intensify their rate of emission when they come into contact with infrared light photons. This increase in activity makes it easier for scientists to observe them. Water molecules are most attracted to photons with specific wavelengths of 79 and 132 μm, which, when absorbed, strengthen the transition’s outline, therefore increasing its visibility. For this reason, this specific water transition has the ability to show us the intensity of the infrared light in the nucleus of galaxies, at spatial scales much smaller than those allowed by direct infrared observations.

Infrared light is produced during events like the growth of supermassive black holes or extreme bursts of star-formation. These events usually occur in extremely dust obscured environments where the optical light is almost completely absorbed by dust grains. The energy absorbed by the grains increases their temperature and they begin to emit thermal radiation in the infrared. Capturing these events can tell us a great deal about how the Universe behaves, so detecting water transitions that can capture this infrared light, is vital.

Moving forward we plan to observe this water transition in more galaxies where dust blocks all the optical light. This will reveal what hides behind these dust screens and help us to understand how galaxies evolve from star-forming spirals, like the Milky Way, to dead elliptical galaxies where no new stars are formed.

Oxford academics give lectures all around the world – but this must be a first.

Dr Anders Sandberg, Senior Research Fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute in the University’s Philosophy Faculty, gave a lecture over Skype from Terminal 5 of Heathrow Airport recently.

He had intended to give the lecture in Madrid, but his flight was one of many to be delayed by a computer bug which struck British Airways during the last Bank Holiday.

When it became clear he was not going to make it to Spain, Dr Sandberg took it in his stride. ‘My dad worked for a Scandinavian airline and so when I was younger my time was spent waiting at airports,’ he said.

‘So I took a quite phlegmatic approach to it. It was probably the first time anybody has given a lecture at a departure gate. Maybe we should have them more often.’

Dr Sandberg’s lecture was titled ‘Reviewing the methods of slowing ageing’. No doubt his audience in Madrid were hooked by the content, but his fellow passengers were baffled.

‘People were wondering what was going on when I started talking about stem cells and ageing,’ he said. 'It must have looked quite weird.’

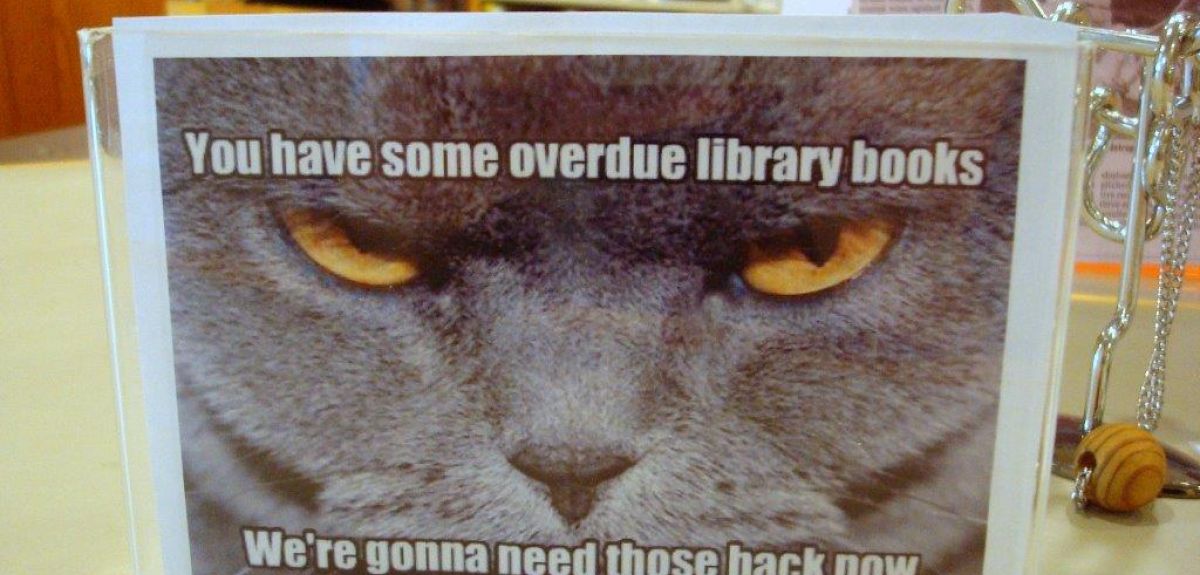

A library copy of a book written by Oxford University historian Dr Roderick Bailey has been returned eight years overdue – and 4,000 miles from where it was borrowed.

A copy of Dr Roderick Bailey’s ‘The Wildest Province: SOE In the Land of the Eagle’, was lent out by Dudley Library in the West Midlands in 2009, and was recently returned to the Boone County Public Library in Burlington, Kentucky.

Luckily for the reader, Dudley Library caps fines at £4.

Dr Bailey, who is Lecturer in the History of Medicine at Oxford University, is happy to speculate about why the reader held onto his book for so long.

‘The book was based on my PhD research (which I did at Edinburgh University) although it took me several years to turn my thesis into something readable,’ he says. ‘At least, I think it was readable.

‘Hopefully this story doesn't suggest that it takes eight years for readers to fight their way through it. Or perhaps, in this case, they so loved the book that they couldn't bring themselves to part with it? I prefer that explanation, although I'm aware that it doesn't really explain its reappearance in Kentucky.’

Dr Bailey has continued to specialise in the study of unconventional warfare and the Second World War in Europe. His last book, published in 2014, was 'Target Italy: The Secret War on Mussolini' (Faber & Faber) which was about Britain's clandestine war on Fascist Italy.

He has also completed a three-year, Wellcome Trust-funded study of the wartime work of professional psychologists and psychiatrists engaged by Britain's Special Operations Executive.

He looked into how they assessed and selected prospective personnel for hazardous, high-risk, high-strain operations in enemy territory, and to do what they could to help those who came home with psychological problems.

This week, we are celebrating what must be the most committed visitors to an Oxford University museum.

They have travelled from Africa to visit the Museum of Natural History every year since 1948.

But although they stay from May to August, they don’t count towards the museum’s visitor numbers or leave any money in the donation box.

They are a colony of 60 pairs of swifts who settle in the ventilation shafts of the tower of the Museum of Natural History.

Keen birdwatcher Ronan Ferguson, 29, says: ‘Like the swifts, I make the journey to Oxford at around this time every year.

'It is a magnificent story that they have been coming here for so long, and there is no better setting to watch them from than from the Museum of Natural History.’

The swifts have been studied by the Edward Grey Institute of Ornithology since 1948.

Earlier this year, the Museum hosted the launch of the Oxford Swift City project, which aims to study swift populations in Oxford. Numbers of swifts in the UK have fallen by 47% since 1995.

The University is partnering with the City Council and the RSPB on this project.

You can keep an eye on the swifts via a live webcam.

Updates on when the chicks are hatched and how they are getting on are also posted on the Museum’s diary.

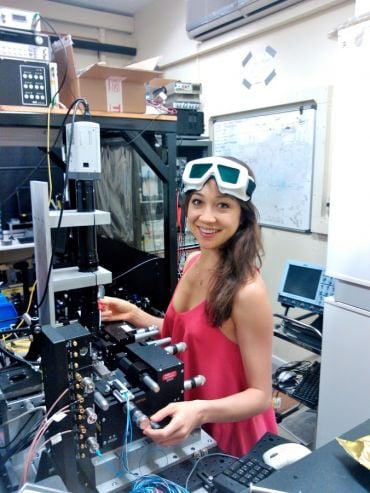

Merritt Moore has achieved what some would call ‘the impossible’: a career as a professional ballet dancer and as an academic quantum physicist. Having quite literally danced her PhD, she is just months’ away from completing her degree in quantum and laser physics. Immediately after graduation she will fly to China to perform at the Beijing National Theatre. Having danced since childhood, she sees great crossover between dance and quantum physics. Earlier this year she combined her passions, collaborating on a meditative science-influenced virtual reality experience called Zero Point Virtual Reality, which is currently running at the Barbican Theatre.

Scienceblog met with Merritt to learn more about fusing her talents and achieving success on her terms.

How did Zero Point Virtual Reality come about?

I have danced In a few of [choreographer] Darren Johnston’s productions, including his original Zero Point live performance in 2013. He takes a spiritual approach to his craft, and would often talk about ‘zero-point’ as a state of calm and zen. I introduced him to the concept of zero point energy as a physics phenomenon. A concept that means that there is always energy, even in empty vacuum, where one imagines no energy could exist. When the Barbican invited Darren to bring back his live production Zero Point, it was a natural progression to continue investigating the notion of ‘zero-point’, but this time using technology and dance. This led us to the virtual reality extension of the show.

We put our ideas together and collaborated with the Games and Visual Effects Lab at the University of Hertfordshire, and now we have a meditation experience running in 360° virtual reality (VR), at the Barbican. The end result is sublime and unique, and I hope people like it.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.In what way did you draw on your physics background for the production?

It is an interactive, sensory experience, people walk from scene to scene, taking in the themes. There are quite a few quantum physics-based elements included. For example, in quantum mechanics the systems are constantly evolving, but the minute you try to measure or interfere with them, they stop. We’ve incorporated this by having a moving rock that only moves when you are not looking at it. The approach is very subtle, and a non-scientist probably wouldn’t spot the connection, but it is there. Hopefully it will trigger people to think in a different way.

I’ve always felt that physics and dance have a lot in common. I have a confession that I sometimes read more physics papers when I am preparing for dance meetings than I do for my own research. It inspires me and makes me think about a process, and how I would explain it to someone without all the lingo and technical terminology that we scientists are so used to. Sometimes we ourselves get so lost in jargon, that we forget what things mean, so how can we expect anyone else to understand? The dance community are not scientists, so they ask a lot of ‘why’ questions, which can really throw you. In science, people rarely ask why? They work from facts, so it just is the way it is. It challenges you to think differently and try harder to break things down.

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

How would you like people to react to it?

The main purpose is to inspire people to view ideas from a different perspective, (literally since with VR you can be placed anywhere). I don’t want to just regurgitate facts, I want to encourage people’s curiosity.

When did you discover your passions for science and dance?

I started dancing when I was 13, which is considered middle-aged in the dance world - most people start as toddlers. Before I discovered dance I was just a girl who loved maths and solving puzzles. I didn’t talk until I was three, so I would communicate through my puzzles. Then I found dance, and was just like ‘this sits in the box of non-verbal activities, I dig this!’ And then, when I found physics, I felt the same way.

You are in your final year at Oxford, what is your thesis investigating?

I am currently working to create large entangled states of light. The more photons - particles of light, you use, the harder it becomes to maintain their quantum properties. Adding more photons makes the whole project more vulnerable to noise, which can destroy their natural state. Understanding how photons behave when you interfere with them can help scientists to explore quantum mechanics phenomena.

Image credit: Merritt Moore

Image credit: Merritt Moore

What drew you to physics?

I love the creativity. Visualising and probing problems that have never been solved before requires a lot of imagination. Often it is mind-bending, and makes no sense. Quantum mechanics is so bizarre - even though the experiment proves again and again that it works, it still makes my head spin.

How do you manage two successful careers in two different fields?

I’ve retired from dance about ten times, burnt my ballet shoes and tried to get so out of shape I would never dance again, but I always come back to it. I honestly never thought I would be a professional dancer. A dance career was a no-go in my family. But I always worked really hard, and achieved the grades I needed. So, when I got to [Harvard] university I was in a position to take a year off to dance with the Zurich Ballet Company. After that I returned for a year, and did the same again the following year, with the Boston Ballet. During the winter break at Oxford I performed with the English National Ballet, and right after leaving here, I will be in Beijing and then on to Edinburgh and Cuba.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a struggle. I’ve worked a lot. Yes, there have been times that I have felt overwhelmed - when I have been in the lab for over 20 hours a day, sometimes literally sleeping there. But it has always been fun. I’ve realised doing both actually helps me to relax. It’s exercising a different part of the brain and the body and I need it.

What is your ultimate goal?

I haven’t figured out what my title will be yet, but I want to shatter all the stereotypes. The dream is to continue combining physics and dance. I want to dance for the next 10 years, become a principal dancer with a company, and still publish physics papers. I was inspired by the film Interstellar, which, for authenticity, channelled real science into its stunning visuals. Physicists shared insights on black holes and worm holes, and they were converted into special effects for the movie. If I’m able to do something like that, then life is complete.

Quantum physics is one of the more polarising sciences, why do you think that is?

Honestly I think physics in general is really under-sold at school. Classes tend to run the same way, with the standard set of problems that have been done so many times that they are probably online. It’s hard to inspire someone when they know that they can google and memorise the facts. That’s not learning. Technology has evolved so far that most of the information is already there. The asset that we bring to the table, as human beings, is creativity.

I think the way science is taught in schools is very isolating, and self-selecting. There is a misconception that science is technical and geeky, but it is collaborative, imaginative and so much fun.

Do you think that there are any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally have never thought that there is anything that a man can do that a woman can’t. So I had always made a point of avoiding the “women in science” physics societies. I felt that by going, I was making a statement that I saw a difference. But, last year I went to my first meeting and it was amazing, and I thought ‘why didn’t I come sooner?’ I really valued the female camaraderie, and hearing people’s shared experiences. It made me realise that there are serious issues. The ratio of women to men in physics has barely budged in 40 years. You hear a lot of talk about change, but the numbers tell a different story.

Little things make a huge difference, particularly to young girls, and I had no idea. I was having lunch at a young STEM event, for girls aged 11-13. One girl causally looked up at a line-up of the old portraits and said ‘oh there’s a woman - I guess she’s the wife or something’, and the girl next to her said ‘Probably not important.’ My heart sank. I had heard of the Oxford Diversifying Portraiture initiative but never thought anything of it. I would shrug my shoulders and think ‘oh well, it’s history’. But listening to the girls’ highlighted how much, if we really care about getting more girls in science, every little change matters.

Zero Point Virtual Reality is running at the Barbican Theatre until 28 May

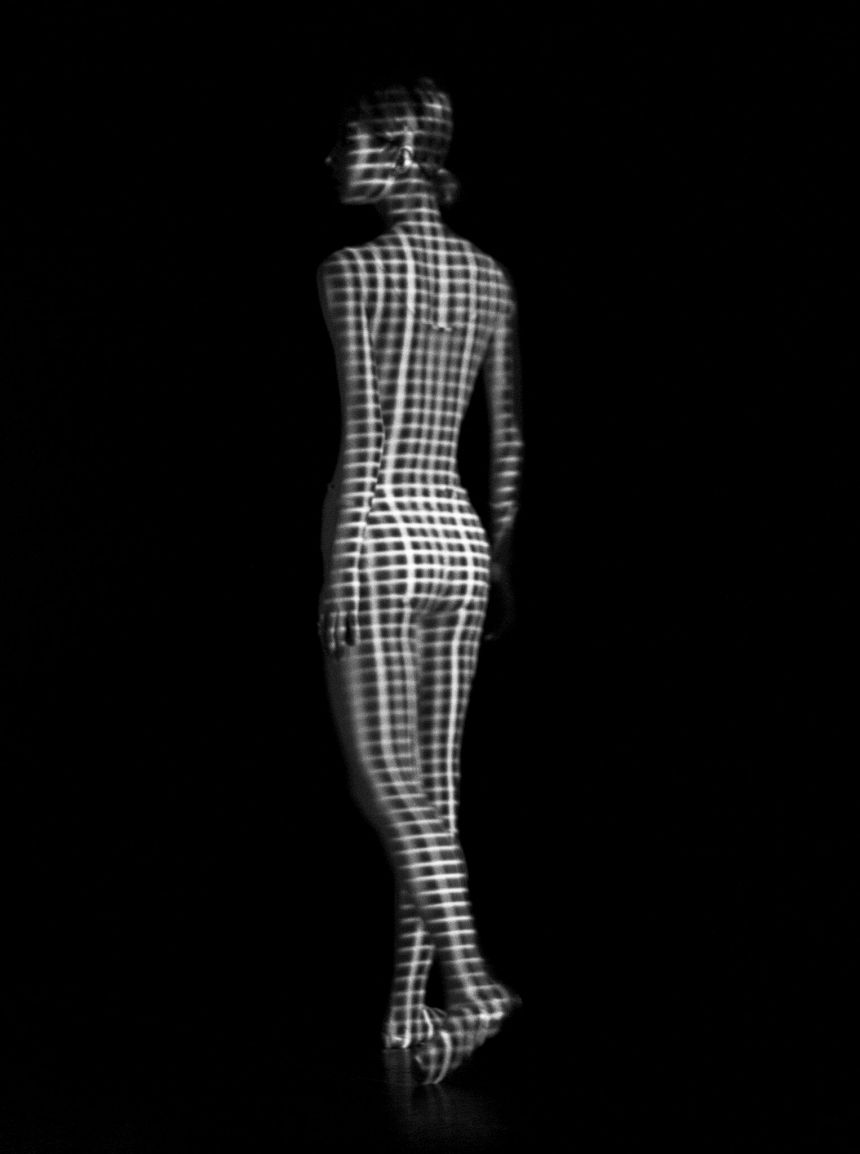

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

- ‹ previous

- 96 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria