Features

Professor Justin Jones of Oxford’s Faculty of Theology and Religion, who has been working on Islam in India for the last 15 years through a variety of different projects, is now working on Sharia (Islamic law), and how it is practised among Muslim communities in modern India.

India, by its constitution, is considered to be a secular state. However, the Indian government has always promised to protect religious freedoms by allowing minorities to live by their own religious laws in their personal and family lives. This means that Muslims in India are still subject to a version of Islamic law (known as Muslim personal law) in family matters – issues such as marriage and divorce, for instance.

In much of the Islamic world, these laws have been codified. But in India, it is very different. There is no code of Muslim family law, and much of it is handled informally, at community level. This means that community religious leaders – often known as the ulama – have a lot of power over individual lives. They make decisions on issues like marriages and divorces that have huge ramifications for individual men and women.

Professor Jones explores the complicated implications of India’s status as a secular state. His work shows that, since India’s constitutional system delegates much legal power to communities themselves, it indirectly makes ‘religious’ leaders more, not less, powerful within their communities. They have exercised authority as legal professionals, issuing legal instructions (fatwas) and running non-government legal forums, like Sharia councils, that handle community cases.

Professor Jones says his work is an attempt to explore what he calls the ‘lived law’ in India. Usually, legal historians have tended to look at the sources left behind by formal legal systems: things like court records, legal statutes or legal digests. This is also true for much legal history of India. But this project considers the exact opposite – how little these formal ideas matter in a society like this. It argues there is a huge gap between these state-driven forms of law, and how law is actually handled and experienced locally. There is a whole world in India where these government involvements in law are entirely absent: community leaders come to their own decisions themselves.

Doing this research means engaging in this informal world. Professor Jones has been working with these communities, in small villages and peripheral urban neighbourhoods across India. He has talked to the scholars actually making these informal decisions, observed ‘Sharia court’ sessions, and been given access to the records of some of these institutions.

Another set of questions raised by this research has been the impact upon Muslim women, who are often most affected by how laws of marriage, divorce, inheritance and child custody are handled. Professor Jones has been working with different Muslim feminist groups within India to discuss their experiences and opinions of this uncodified system. In August 2017, he teamed up with Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA), India’s foremost Islamic feminist group, to run a workshop with young activists in Delhi. He and a number of activists and NGO leaders based around India ran sessions discussing both Sharia laws and Indian laws to help them find ways to empower the women they work with. This gave these activists the opportunity to share their knowledge and experiences with academics and writers, and consider different strategies for improving women’s rights.

The BMMA argue that Islamic law and the Islamic constitution both uphold women’s rights, and offer gender justice and protection. They argue that religious scholars have sustained a flawed, patriarchal interpretation of Islam. They are making arguments from Islamic principles, using religion as a basis for building a new language of women’s rights. They have even set up their own Sharia councils, led by women, to offer their own more gender-just interpretations, and they are now arguing for an overhaul of Muslim family laws in India.

In the coming years, Professor Jones hopes to look further into Islamic feminism, and the efforts of these groups to build an equal and fair family law, both within India and around the world.

Nathalie Seddon, Professor of Biodiversity & NERC Knowledge Exchange Fellow at Oxford’s Department of Zoology, discusses the launch of her new Nature-based Solutions Initiative , which took place at the Adaptation Futures 2018 Conference, in Cape Town last week. Through policy advice and advocacy, the interdisciplinary, research-led programme aims to increase the use of natural solutions in the fight against climate change.

Climate change, biodiversity loss and poverty are inextricably linked. Not only do communities from the poorest nations suffer the worst effects of climate change, they also experience the highest rates of loss and damage to their natural ecosystems. However, nature is our best line of defence against harmful environmental change. In particular, it is becoming increasingly clear that the protection and restoration of nature can be the most cost-effective way of dealing with both the causes and consequences of climate change.

For example, one recent study indicates we could achieve a 30-40% reduction in CO2 emissions by restoring natural habitats across the globe; while another shows how natural coastal habitats have protected millions of dollars’ worth of property during recent hurricanes in America.

In other words, there is growing evidence that nature-based solutions not only help to slow warming, but shield us from the impacts of change and protect the ecosystems on which our health, wealth and wellbeing so fundamentally depends.

Despite this, nature-based solutions are not being implemented across the globe, and they receive very little funding. There are three major reasons for this. First, evidence for the benefits of nature in a changing world is very scattered. Second, there is a lack of knowledge exchange between scientists, policy makers and practitioners: too much ecosystem science is done in isolation from the end-users, and too many adaptation policy decisions are made without considering the science. And third, more broadly, there is a general lack of appreciation in business and government of our fundamental dependency on nature, especially in a warming world.

To address these issues, alongside partners from the conservation and development sectors, we have co-created a new interdisciplinary programme of research, research translation, policy advice and advocacy called the Nature-based Solutions Initiative.

The initiative was launched last week at the Adaptation Futures 2018 conference in Cape Town, which is the largest annual gathering of researchers, practitioners and policy makers looking for long-term sustainable solutions to the impacts of climate change.

Our presentation included the release of a new interactive online science to a policy platform, which makes information about climate change adaptation planning across the globe openly available, easy and interesting to explore.

The platform includes country by country details of who is doing what, in terms of incorporating nature-based solutions into their adaptation plans, and is linked to an extensive database of scientific evidence for the effectiveness of such approaches.

This initial version showcases adaptation plans in the climate pledges of all signatories of the Paris Agreement, and highlights the prominence of Nature-based Solutions to climate change hazards. Through this work we aim to facilitate the global stock-take of the Paris Agreement and provide a baseline against which changes in ambition for Nature-based Solutions to climate change adaptation can be monitored and increased.

By helping decision makers and practitioners access and understand evidence for the effectiveness of nature-based approaches to dealing with the impacts of climate change, our aim is to tackle the twin challenges of conserving biodiversity and building socio-ecological resilience in a warming world.

WHAT ARE NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS TO CLIMATE CHANGE?

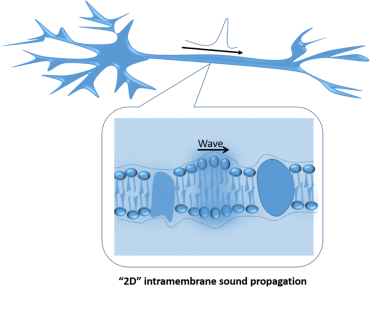

Shamit Shrivastava, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Engineering Science, writes about a recent finding that has far-reaching consequences for the fundamental understanding of the physics of the brain. The research was conducted in partnership with Professor Matthias F Schneider at the Technical University in Dortmund, Germany.

The findings, published in the Journal of Royal Society Interface, provide the experimental evidence that sound waves propagating in artificial lipid systems that mimic the neuron membrane can annihilate each other upon collision – a remarkable property of signals propagating in neurons that was considered to be inaccessible to an acoustic phenomenon.

Nerve impulses are believed to propagate in a manner similar to the conduction of current in an electrical cable. However, for as long as the electrical theory has been around, scientists have also been measuring various other physical signals that are equally characteristic of a nerve impulse, such as changes in the mechanical and optical properties that propagate in sync with the electrical signal. Furthermore, several studies have reported reversible temperature changes that accompany a nerve impulse, which is inconsistent with the electrical understanding from a thermodynamic standpoint.

To address these inconsistencies, researchers had previously proposed that nerve pulse propagation results from the same fundamental principles that cause the propagation of sound in a material and not the flow of ions or current. In this framework, the electromechanical nature of the nerve impulse, also known as an action potential, emerges naturally from the collective properties of the plasma membrane, in which the sound or the compression wave propagates. Thus the characteristics of the wave are derived from the principles of condensed matter physics and thermodynamics, unlike the emphasis on molecular biology in the electrical theory.

The suggestion has been highly controversial because of the well-accepted and widely successful nature of the electrical basis of nerve pulse propagation in spite of its few inconsistencies. As a wave phenomenon, nerve pulse propagation has remarkable properties, such as a threshold for excitation, non-dispersive (solitary) and all-or-none propagation, and annihilation of two pulses that undergo head-on collision. Moreover, sound waves are generally not associated with such characteristics, rather sound waves are known to spread out, disperse, dissipate, superimpose and interfere, which is counter-intuitive given the properties of nerve impulses.

Therefore, experimental evidence for such a phenomenon was crucial, which was provided by us in 2014. We showed that sound or compression waves can indeed propagate within a molecular thin film of lipid molecules, mimicking action potentials in the plasma membrane. Remarkably, even in such a minimalistic system that is devoid of any proteins and macromolecules other than lipids, these waves behave strikingly similar to nerve impulses in a neuron, including the solitary electromechanical pulse propagation, the velocity of propagation and all-or-none excitation. These characteristics were shown to be a consequence of the conformational change or a phase transition in the lipid molecules that accompany the sound wave. Thus only when sufficient energy is provided to cause a phase change in the lipids (fluid to gel-like), the entire pulse propagates otherwise nothing propagates, the so-called all-or-none propagation.

Now, in research published in the Journal of Royal Society Interface, we have shown that these waves can even annihilate each other upon collision, just like nerve impulses. Even from a purely acoustic physics perspective, this is a remarkable finding. The amplitudes of two sound pulses colliding head-on typically superimpose linearly before passing each other unaffected. Even nonlinear sound pulses, such as solitons, typically remain unaffected upon collision, which was a major criticism of the proposed acoustic theory of nerve pulse propagation.

With the observation of annihilation of colliding sound pulses in the model lipid system, we have shown that qualitative characteristics of the entire phenomena of nerve pulse propagation can be derived solely from the principles of condensed matter physics and thermodynamics without the need for molecular models or fit parameters of the electrical theory. We have demonstrated a unique acoustic phenomenon that combines all the observable characteristics that define the propagation of nerve impulses. This strongly suggests that the underlying physics of propagation of sound and nerve impulses is indeed one and the same.

Sound waves propagating in artificial lipid systems that mimic the neuron membrane can annihilate each other upon collision.

Sound waves propagating in artificial lipid systems that mimic the neuron membrane can annihilate each other upon collision.Don’t be fooled by popular wisdom — when it comes to eating disorders, books can be just as harmful as other forms of media, finds Francesca Moll...

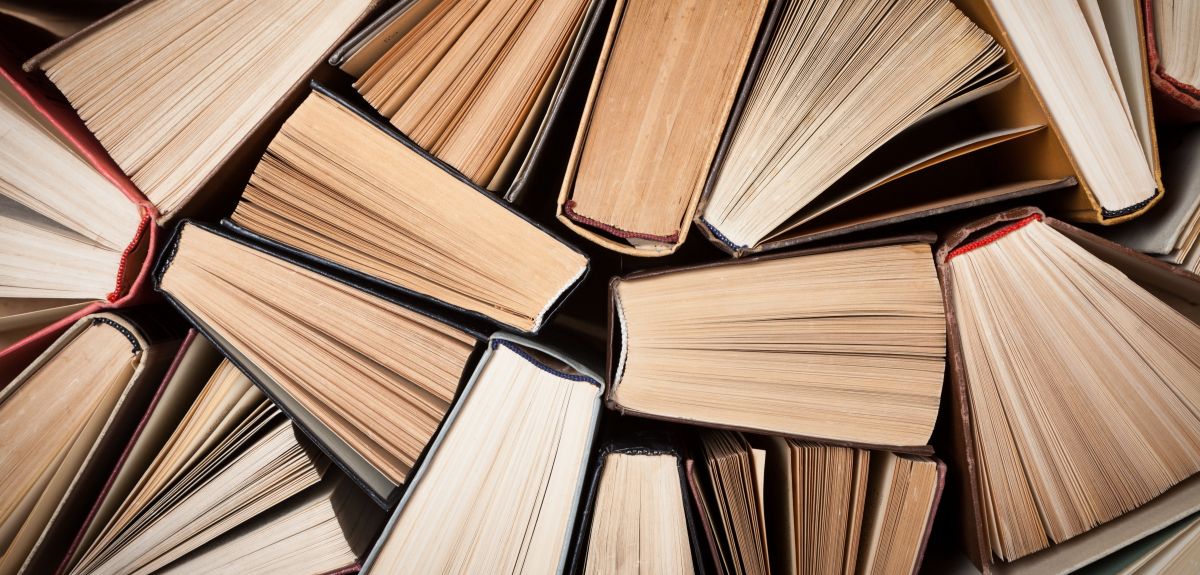

It is a truth seemingly universally acknowledged that the mainstream media can have a negative effect on eating disorders. But what about books? According to Dr Emily Troscianko, of Oxford’s Medieval and Modern Languages Faculty, we ignore them at our peril.

Dr Troscianko, whose research spans cognitive studies and German literature, also writes a blog for Psychology Today based on her personal experience with anorexia and the science of eating disorders. She was inspired to bring together the two sides of her research when she realised how little was known about the relationship between eating disorders and reading.

As part of a Knowledge Exchange Fellowship with TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities), she teamed up with BEAT, the UK’s largest eating disorders charity, to find out how these illnesses might affect how people engage with literature, and whether reading could help sufferers adopt more healthy ways of thinking.

Together they came up with a comprehensive survey of over 60 questions, assessing how mood, self-esteem, body image and diet and exercise habits were affected by reading. This was filled out by nearly 900 respondents in varying stages of eating disorder recovery, both from BEAT’s UK volunteer network and via sister charities in the US, Canada, and Australia.

The results proved quite a shock: certain books seemed to make illness worse, and these were the ones that the theory of ‘creative bibliotherapy’ predicts would be most helpful for recovery. It is generally assumed that illness narratives, where the main character goes through the same illness as the reader, would be best at generating insight and a desire to recover.

But Dr Troscianko found that in fact the reverse was true: an overwhelming majority of respondents reported decidedly negative effects on their illness from reading such fiction. Indeed, rather distressingly, it seems that many were aware of the negative effect on their mood that they caused, and sought them out deliberately with the intention of making themselves more ill.

Although these works rarely explicitly supported disordered eating, it seems that the moral was getting lost thanks to the restrictive thinking patterns of the readers. Sufferers ended up getting trapped in an endless ‘positive feedback loop’ where the unhealthy mindset that sent them there in the first place was reinforced by reading the same thing described on the page.

‘It’s clear that people are filtering out the stuff that doesn’t accord with the eating disorder mindset and just seeing the positives, the control, the sense of superiority, all those things that are covered in the early parts of the books before the recovery happens, and not seeing that there’s any critical angle on them,’ says Dr Troscianko.

Although it’s usually glossy magazines and TV shows that are blamed for encouraging disordered eating patterns, it’s clear books can be just as harmful, although in different ways.

‘I wonder whether in a way we’re kind of image-saturated. Skeletal catwalk models are still shocking and off-putting and fascinating to some extent, but I wonder whether encountering a description of such a person in words actually might do something equally problematic, just in a different way.

‘One of the things I get frustrated about is that people tend to assume because it’s literature it must be doing good. And there’s no reason to assume that.’

On the other hand, Dr Troscianko also found that many books had a helpful effect on eating disorders. These varied greatly depending on individual taste, with everything from Harry Potter to Pride and Prejudice being mentioned. What they had in common was that they helped to jolt the respondents out of their established thinking patterns by showing them that something else was possible outside of these confining boundaries, or else simply boosted their mood by providing a much-needed escape.

Rather than a narrow focus on the grim reality of eating disorders, then, therapeutic fiction may need to take a more oblique approach. Dr Troscianko is hopeful about the possibilities of metaphor, extended allegory, or even a science fiction or fantasy setting.

‘Eating disorders, all mental illnesses probably, are so much about getting stuck in very narrow circles of thinking and not being able to break out of them, that anything that breaks into that and just forces you to widen your gaze for a moment and to think differently, even just very temporarily, is powerful.’

Dr Troscianko is keen to emphasise that this survey is just the first step; she hopes to back up the subjective data of this self-reported survey with more in-depth psychological experiments.

‘The trouble is you do a little bit of research and then you find out how much you don’t know. But we’re getting there.’

You can read Dr Troscianko’s blog here, as well as following her latest projects — including developing an app to help eating disorder recovery. Visit the BEAT website here.

As MPs give Heathrow Airport's proposed third runway the green light, Professor David Banister, Emeritus Professor of Transport studies at Oxford University, sheds light on the issue of transport inequality and just why the proposed expansion has sparked such controversy.

London Heathrow (LHR) is the busiest airport in the UK with 48 million passengers beginning or ending their journeys in London, and an additional 28 million passengers making interconnecting flights to other destinations. The 3rd Runway will increase the total capacity to 130 million (+71%) and the number of flights will increase to 740,000 per annum (+56%). But who will be the new passengers flying from LHR?

About half the population of Great Britain has flown in the last year (47%), and this figure has been stable over the last 15 years. Most of those that do fly make one or two trips a year (31%). This means that 10% make about 60% of all flights, and as might be expected these people are mainly from the highest income groups. The richest 10% make 6.7 times as many trips by air as the poorest 10% of the population. The inequality in air travel in Great Britain is far higher than any other form of travel with the exception of High Speed Rail (10.3 times). Figures for the other forms of transport are much lower, with the difference for car travel being 2.75 times and for the bus the poor make more trips than the rich.

Some might argue that low cost airlines have helped rebalance this inequality, but the evidence would suggest that cheaper flights have enabled those already flying to travel more frequently and possibly to save money. Inequality is important as it reflects on societal values and the argument that society as a whole should gain. But it is equally important to identify who are the winners and who are the losers – it is about fairness and justice. This is particularly the case when large amounts of public money are involved. The new runway is estimated to cost £14 billion, with a similar amount being needed to improve road and rail links to the airport. A substantial part of this funding will come from Government and Transport for London.

It is likely that low income people will make only limited use of the new runway, but they will also be impacted by it indirectly through additional CO2 emissions. Overall, the richest 10% of households produced 3 times the levels of CO2 emissions than those from the poorest 10% of households, but for transport the difference is between 7-8 times and 10 times for aviation. New runway capacity at LHR will increase this difference, as more rich people fly further and more frequently. Local pollutants (e.g. NOx) and the noise impact are also likely to increase from the additional planes (and traffic). This means that it becomes much harder to meet CO2 reduction targets and improve local air quality, and air quality around LHR is already very poor.

Even the argument about the importance of increased airport to the local and national economies is weak. Business air travel accounts for about 20% of all passengers in Great Britain, with the figure for LHR being higher (30%). This market has been relatively stable, as the growth in air travel has come from leisure travel and visiting friends and relatives. In addition, UK residents are spending more overseas than others do coming to the UK. In 2016, there were 71 million overseas visits from UK residents and the total spend was £43.8 billion. There were 38 million visits to the UK and the total spend was £22.5 billion.

The clear conclusion is that on grounds of inequality, environment and spend, building additional airport capacity at LHR does not add up, as it will enable the richest 10% to fly even more and spend their money overseas. It will be the poorest 10% that stay in the UK, and they will suffer from even higher levels of CO2 emissions and poorer levels of air quality.

This analysis is based on National Travel Survey data (2002-2012) and Air Passenger Surveys carried out for the Civil Aviation Authority.

Read the full article on The Conversation here

This analysis of air travel in the UK forms part of Professor Banister’s new book Inequality in Transport, which will be published by Alexandrine Press on 12th July.

- ‹ previous

- 70 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria