Features

By Jesús Aguirre Gutiérrez, researcher at the Environmental Change Institute, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, and the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, The Netherlands.

The tropical forest canopy is one of the Earth’s underexplored frontiers. To understand how these unique environments respond to climate change a team from the Ecosystems Lab at the University of Oxford and partner institutes in Ghana gathered evidence from the treetops, finding drier forests are at greater risks.

Our natural world is facing unprecedented changes in the distribution of biodiversity – the variety of life on earth – at local and global scales. Around one million species are threatened with extinction, posing an imminent threat to the functioning of ecosystems and to human wellbeing.

Image: A tree climber collecting leaf samples 30 m up a rainforest tree (Ankasa, Ghana). © Yadvinder Malhi.

In our new study, recently published in Nature Communications, we investigate if and how climate change has affected the diversity of tropical ecosystems in West Africa over the last decades. In particular, we wanted to understand if wetter and drier tropical forests responded in different ways to the same drivers of change.

For this study we conducted fieldwork in Ghana over six months. The field campaign was led by Dr Imma Oliveras and Dr Stephen Adu Bredu and coordinated by co-authors Theresa Peprah and Agne Gvozdevaite. It formed part of a global effort. More than 25 research assistants from KNUST University and Forestry Institute of Ghana (FORIG) participated in the field campaign and were trained in the sampling techniques and scientific protocols for undertaking the research.

Image: Albert Aryee labels plastic bags for collecting samples of leaves. All bags must be labelled with a unique code so that each leaf can be tracked to a branch, tree, and site. © Imma Oliveras

During the campaign we visited clusters of sample plots at three sites, stretching along a climate gradient from humid ancient rainforest through to parched try forest and savanna. We sampled leaves and branches from 299 trees. These were very long days, usually starting at 4.30 am with a group breakfast and by 6 am we would be already working in the field. We would finish the fieldwork at around 3 pm and then work in the field laboratories until 10 pm. Some of the research assistants – who were masters and undergraduate students at the time – have pursued further postgraduate studies after the experience and successfully found scholarships in Ghana, Europe and the US.

Image: Working in the field laboratory. © Imma Oliveras

Image: Working in the field laboratory. © Imma Oliveras

When starting this research, we expected that a drying trend would be reflected in overall diversity decreases for all tropical forests. However, we found that forest communities in drier sites experienced on average stronger declines in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity across time than forest communities in wetter areas.

This means that drier forests are transitioning towards increasingly more homogenous forest communities, diverging further from wetter forests in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity. In contrast, wetter forests showed on average increases in functional and taxonomic diversity, which could be the result of their higher atmospheric and ground water availability in comparison to that available for drier forests. Overall, climatic and soil conditions partly explained the changes in diversity and differences in responses between drier and wetter tropical forests in West African.

Stephen Adu-Bredu and Theresa Peprah from CSIR-Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, described that some of the most challenging things to do during the fieldwork were waking up daily at 3am in order to get to the field around 4am for predawn water potential measurements, as well as climbing of the trees at this hour of the day. They say: ‘The dry season CO2 exchange measurement was difficult and frustrating. One can spend over an hour or even a day on a single leaf, and the measurements are to be carried on three leaves per branch, as the protocol demands.’

Dr Imma Oliveras, senior study author and Deputy Programme Leader on Ecosystems at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, reflects on the field campaign: ‘To me this field campaign was an incredible enriching experience. These were busy days of knowledge exchange. I would be training local students on scientific methodologies, and they were teaching me about the local flora as well as about the local forests and of the Ghanaian culture and traditions.

‘Some forests had taboo days in which we were not allowed to go to the forest and we would use for catching up on lab work. We would also exchange knowledge in other aspects, such as cuisine. I learned to make fufu and I taught them to cook Spanish omelets. Scientifically, I enjoyed training the research assistants in both data collection, data curing and data analyses, and most participants are now co-authors of other related research.’

Image: Part of the team at base camp. © Yadvinder Malhi.

Image: Part of the team at base camp. © Yadvinder Malhi.

In our study we did not assess on how diversity changes affect ecosystem functioning. However, there is ample evidence showing that decreases in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity could cause loss of forest functions, such as resources uptake, cycling and biomass production and resilience to a changing climate. Therefore, the ecosystem functions of communities that show decreases across all three facets of diversity could be especially vulnerable under a drying climate.

Overall, our study found that drier forest communities have undergone biodiversity homogenisation due to a warming and drying climate, which could ultimately have negative impacts not only on the functioning of ecosystems but also on their contribution to people’s wellbeing and livelihoods.

Image: Heading into the field. © Yadvinder Malhi.

Image: Heading into the field. © Yadvinder Malhi.

The work was funded through a European Research Council Advanced Investigator Grant to Prof Yadvinder Malhi, coupled with a Royal Society Africa Capacity Building Award. The transects of field sites where this work was conducted were established with the support of a NERC Standard Grant.

Citation: Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J., Malhi, Y., Lewis, S.L. et al. Long-term droughts may drive drier tropical forests towards increased functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic homogeneity. Nat Commun 11, 3346 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16973-4

COVID-19 sent the global public back to more trusted news sources and more people than ever are paying for news from leading organisations, according to this year’s Digital News Report from Oxford’s Reuters Institute. But, the Institute believes, a shift to social media and mobile platforms remains the underlying trend in news consumption.

Based on research in 40 markets around the world, the Reuters’ report gives a snapshot of the state of news before and during the pandemic. The Institute found that COVID-19 saw a major increase in all age groups watching TV news, as people sought reliable information. The report shows, social media and online sites also saw significant increases, although newspaper sales – adversely affected by the lockdown have declined. But trusted brands have done ‘disproportionately well’ online.

According to the Institute, ‘The change of underlying preferences is even more clear when we ask people to choose their main source of news. The UK shows a 20-percentage-point switch in preference from online to TV between the end of January and the start of April.’

The report reveals, ‘Industry data also indicate strong traffic increases for online news with the most trusted brands often benefiting disproportionately. The BBC reported its biggest week ever for UK visitors, with more than 70 million unique browsers as the lockdown came into effect.’

Although most surveying was done at the beginning of the year, the Institute carried out additional research in April, to see the impact of the pandemic. It reveals, ‘At around the peak of the lockdowns, trust in news organisations around COVID-19 was running at more than twice that for social media, video sites and messaging applications where around four in ten see information as untrustworthy.’

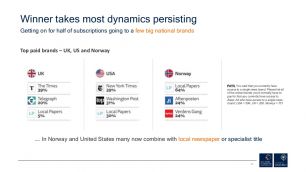

However, the Institute found, subscriptions soared to well-known news organisations, which have gone behind ‘paywalls’, even before the virus. In the US, during 2019, there was a 4% increase to 20% of people paying for online news, while in Norway there was an 8% rise to 42%. On average, some 26% in Nordic countries now pay for news subscriptions.

In the UK, the biggest subscription brand is The Times, which was first to go behind a paywall, with 39% share of the subscription market. The Telegraph has a 20% share. Meanwhile, in the US, where local papers are important players in the news market, the New York Times has a 39% share of the market and the Washington Post holds 31%, just ahead of local papers on 30%.

In the UK, the biggest subscription brand is The Times, with 39% share of the subscription market. The Telegraph has a 20% share. Meanwhile, in the US, the New York Times has a 39% share of the market and the Washington Post holds 31%

But, according to the report, ‘A large number of people remain perfectly content with the news they can access for free and we observe a very high proportion of non-subscribers (40% in the US and 50% in the UK) who say that nothing could persuade them to pay.’

Rasmus Nielsen, the report co-editor, says, ‘We see clear evidence that distinct, premium news publishers are able to convince a growing number of people to pay for quality news online. But most people are not paying for online news, and given the abundance of freely available alternatives, it is not clear why they would. In such a competitive market, only truly outstanding journalism can convince people to pay.’

Nic Newman, senior research associate, at the Reuters Institute, writes ‘Journalism matters and is in demand again. But one problem for publishers is that this extra interest is producing even less income...it is likely we’ll see a further drive towards digital subscription and other reader payment models which have shown considerable promise in the last few years.’

Journalism matters and is in demand again

He adds, ‘Looking to the future, publishers are increasingly recognising that long-term survival is likely to involve stronger and deeper connection with audiences online.’

A major concern among the Institute’s responders was misinformation, but while Facebook was seen as unreliable by a third, accredited journalists are not generally perceived to be the problem. Before the peak of the pandemic, more than half of Reuters’ global sample said they were ‘concerned about what is true or false on the internet’. Globally, journalists were seen as unreliable by 13%, but at the top of the list were politicians, with 40% believing they provide false or misleading information. And Facebook aroused concern among 29%.

Trust is a major issue. According to the report, ‘In our January poll, across all 40 markets, less than four in ten (38%) said they trust ‘most news most of the time’

Trust is a major issue. According to the report, ‘In our January poll, fewer than four in ten (38%) said they trust ‘most news most of the time’ – a fall of four percentage points from 2019. Less than half (46%) said they trust the news they use themselves while trust in search (32%) and social media (22%) is even lower.’

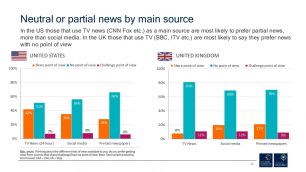

Finland is most trusting, with some 56% saying they trust most news most of the time. Ireland registers 48% trust, Germany 45% Australia 38%. But US responders registered news trust levels of less than 30% and the UK, following Brexit and a bruising General Election, registered 28% – with trust levels in France at just 24%. According to the Institute, ‘Our survey shows that the majority (60%) still prefer news that has no particular point of view.’

A significant minority (28%) prefer news that shares or reinforces their views

But it found a significant minority (28%) prefer news that shares or reinforces their views, ‘Partisan preferences have slightly increased in the United States since we last asked this question in 2013 but even here a silent majority seems to be looking for news that at least tries to be objective.’

In the US, ‘Both politics and the media have become increasingly partisan over the years, we do find an increase in the proportion of people who say they prefer news that shares their point of view – up six percentage points since 2013 to 30%. This is driven by people on the far-left and the far-right who have both increased their preference for partial news sources.

Initially at least, COVID-19 did provide a boost for news but this fell away, once news organisations turned to more critical reporting, ‘Subsequent polling...shows that the COVID-19 crisis did temporarily increase trust levels in the news media in the early stages of lockdown...this has fallen almost as quickly as the media has stepped up its criticism of government and official handling of the pandemic.’

The report emphasises, ‘While the COVID-19 crisis has reinforced the need for reliable and trusted news, the report argues that the next 12 months are likely to see significant changes in the media environment as severe economic pressures combine with political uncertainty and further consumer shifts to digital, social and mobile environments.’

But it concludes, ‘The COVID-19 lockdown has reminded us both of the value of media that bring us together, as well as the power of digital networks that connect us to those we know and love personally....’

The COVID-19 lockdown has reminded us both of the value of media that bring us together, as well as the power of digital networks that connect us to those we know and love personally

However, ‘The biggest impact of the virus is likely to be economic...The coronavirus crisis is driving a cyclical downturn in the economy hurting every publisher, especially those based on advertising, and likely to further accelerate existing structural changes to a more digital media environment...Reader payment alternatives such as subscription, membership, and donations will move centre stage, but as our research shows, this is likely to benefit a relatively small number of highly trusted national titles as well as smaller niche and partisan media brands....

‘Despite this, there are some signs of hope. The COVID-19 crisis has clearly demonstrated the value of reliable trusted news to the public but also to policymakers...and others who could potentially act to support independent news media. The creativity of journalists has also come to the fore...Fact-checking has become even more central to newsroom operations, boosting digital literacy more widely and helping to counter the many conspiracy theories swirling on social media and elsewhere.’

The figures are from a YouGov online survey conducted at the end of January, early Feburary in 40 countries of 80,155 adults (around 2,000 per country).

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased public awareness of the extent to which society - from farms to care homes - relies on the availability of a low-wage workforce.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased public awareness of the extent to which society - from farms to care homes - relies on the availability of a low-wage workforce

Media coverage during the coronavirus crisis has, in many cases, highlighted the risks to which these workers are exposed, alongside the low pay and difficult working conditions they endure (such as lack of personal protective equipment). In recent months, delivery drivers, food producers, and supermarket staff have been recognised as ‘key’ workers. Many of those lower-waged occupations, which have been acknowledged as essential in the crisis, are heavily dependent on migrant workers.

Many of those lower-waged occupations, which have been acknowledged as essential in the crisis, are heavily dependent on migrant workers

In this context, it is important to ask if, and how, future immigration policies should take account of the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic? This question is important for countries around the world but, at the moment, it is particularly relevant for the UK.

The COVID-19 emergency comes at a time when the UK is on the verge of shifting to a new immigration system, when the Brexit transition period comes to an end.

The selection process of immigration systems and essential workers

Immigration systems in high-income countries are typically more open towards workers in higher-paid jobs, while imposing restrictions on those coming to work in lower-paid occupations.

For example, work visas for high-skilled jobs are less likely to be restricted by numerical caps and requirements to look locally first for workers. They will often have a path to permanent residence and citizenship. By contrast, employers recruiting migrant workers in low-skilled jobs will face more complex bureaucracy, such as detailed regulations on pay and working conditions. There may be a maximum stay and no path to permanent status. So, in many cases, immigration into ‘essential’ but low-pay jobs is strongly restricted.

In many cases, immigration into ‘essential’, but low-pay jobs, is strongly restricted

Currently, the UK imposes strong restrictions on immigration for work purposes from outside the European Union, while EU nationals enjoy free movement for work purposes. As a consequence, during the pandemic, EU nationals have played major roles in ‘essential’ low wage sectors of the economy. For example, a large majority of seasonal harvest workers in the UK come from the EU. This workforce is essential, since significant labour shortages in the sector could threaten the UK food supply.

However, free movement will soon end and the UK Government is proposing to restrict substantially the immigration of EU nationals into jobs that are not considered high-skilled.

How would this affect the supply of essential workers in the UK?

Many essential workers from the EU, including NHS nurses and doctors, are likely to be eligible for visas under the proposed immigration system. Obviously, there is a question of whether as many would still be interested in living in the UK, given the different immigration status conditions. We will soon find out. But many other essential workers from the EU, such as those in social care or food manufacturing, are less likely to qualify for a visa.

Many essential workers from the EU, including NHS nurses and doctors, are likely to be eligible for visas under the proposed immigration system...But many other essential workers from the EU, such as those in social care or food manufacturing, are less likely to qualify for a visa

Estimates vary of the share of current workers in essential occupations who do not meet the proposed post-Brexit visa requirements. The discrepancy comes, in part, because there is no unique definition of an ‘essential’ worker.

In a recent paper, I wrote with colleagues Madeleine Sumption and Marina Fernandez-Reino, we find that 53% of EU-born and 42% of non-EU-born full-time employees, in essential occupations in the UK, do not meet the proposed requirements for a work visa. The Migration Observatory updated these numbers using a slightly different definition provided by the UK’s Office for National Statistics and found similar shares: 58% for EU-born and 49% for non-EU-born workers.

Will the pandemic change UK policymakers’ views about how essential workers should be treated in the post-Brexit immigration system?

The current pandemic might convince some policymakers that some industries have strategic value and need special access to a sufficient workforce - so they are in a position to provide essential goods and services in case of a new pandemic or a second wave.

The current pandemic might convince some policymakers that some industries have strategic value and need special access to a sufficient workforce - so they are in a position to provide essential goods and services in case of a new pandemic or a second wave

This could see support for that rationale in post-Brexit immigration policy planning. But the current pandemic provides little guidance on more fine-grained questions, such as which industries should be considered ‘strategic’, in terms of the immigration system.

Others might point out that the current emergency has led to worker lay-offs in other industries – so there is more potential than usual to hire within the domestic labour market. But, while this sounds like a straightforward solution, in the past, even in periods of high domestic unemployment, many employers have still preferred to recruit from abroad. The reasons behind those preferences are complex, but there is evidence that migrants are particularly targeted for jobs that are riskier or require greater physical intensity.

Deciding between these, and other options, is not straightforward and involves a major degree of subjectivity. Expect much more debate on these issues over the next few months.

Carlos Vargas-Silva, Director and Associate Professor, Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford

A collaboration between Oxford scientists and a distillery has produced a special gin called Physic Gin. Based on 25 ingredients found in the Oxford Botanic Garden, the history of this new spirit stretches back 400 years to the garden’s creation in 1621. With this week’s reopening of the Oxford Botanic Garden following months of closure during lockdown, it would seem there are several reasons to raise a glass.

Oxford Sparks’ caught up with Professor Simon Hiscock, Director of the Oxford Botanic Garden for their latest podcast. He tells Sparks how he came up with the idea for Physic Gin from the moment he started in his new role. He says: ‘I wanted to commission a gin because of the great botanicals we have here and the history of the garden.

The intention was for it to grow herbal, medicinal plants, that would then be used in the teaching of herbal medicine for the medical students of Oxford. Gin was also a medicine in its own right, created in the 17th century in Holland and Belgium, for the treatment of fever.

‘The garden was founded in 1621 by Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby, but it wasn’t planted up until the 1640s. Jacob Bobart, the garden’s first director, was an excellent gardener and also ran The Greyhound Tavern just across the road from the Botanic Garden. He started planting the garden and by 1648 he had about 1600 plants here and he made a list – a Catalogus Plantarum – almost like a field notebook, and this little notebook is the inspiration for Physic Gin. Among those 1600 plants are many botanicals that we would use to flavour gin today and importantly juniper because juniper is the base fruit ingredient for flavouring the alcohol.’

The name Physic Gin derives from the fact that the garden was founded originally as a physic garden; a medicinal garden, as Simon explains: ‘The intention was for it to grow herbal, medicinal plants, that would then be used in the teaching of herbal medicine for the medical students of Oxford. Gin was also a medicine in its own right, created in the 17th century in Holland and Belgium, for the treatment of fever.’

After chatting to his local pub landlord about the idea, Simon was put in touch with The Oxford Artisan Distillery, and the collaborative mixing of spirits and minds began.

Dried chamomile flowers

Dried chamomile flowersThe team of scientists and distillers worked closely together on the recipe for two months to ensure that that the history of the garden went into the bottle with the optimum flavour preserved.

Francisco says: ‘We are always playing. We use spices, fruits, flowers and fresh herbs. There’s a base distillation and some of the botanicals need to be distilled separately.’

Incredibly, 25 botanicals have gone into the Physic Gin. They have an almost poetic sound when read aloud: ‘Juniper, coriander seed, angelica root, lemon peel, liquorish root, angelica seed, Japanese bitter orange peel, Grapefruit peel, key lime peel, sweet fennel seed, almonds, poppy seed, wild hops, chamomile flower, wormwood, artichoke leaf and bayleaf...’

Black pine in Oxford Botanic Garden

Black pine in Oxford Botanic GardenAs we start to emerge from lockdown, it’s now possible to start to explore the sources of these inspirations in person as The Oxford Botanic Garden reopens on 22 June, and for those in need of a medicinal tonic, Physic Gin is available to order now.

Listen to ‘Why is Oxford’s Botanic Garden Making Gin?’ on Oxford Sparks.

Find out more about Physic Gin from The Oxford Artisan Distillery.

The Oxford Botanic Garden is now open to visitors. Find out more and book a ticket.

Discover more episodes of the Oxford Sparks ‘Big Questions’ podcast.

We got the ‘green’ in green issues from the chlorophyll in plants. But the botanical world – which drives the planet’s ecosystems – is the Cinderella science, struggling for resources and recognition, struggling even to keep up with the rate of extinction. And there’s a reason for that – or quite a few, says Oxford Professor of Systematic Botany, Robert Scotland.

While arbitrary international targets are set for ‘saving species’, loss is very much a reality in the funding-strapped world of plants. The truth is, plants have been disappearing at the rate of at least two species a year, every year, for the last 250 years (but that’s a very conservative estimate, we don’t really know).

There are a lot of unknowns - and very big numbers - in the world of plants. Of the 370,000 known species of flowering plants, at least half are so poorly known they are almost invisible to any conservation effort

There are a lot of unknowns - and very big numbers - in the world of plants. Of the 370,000 known species of flowering plants on Earth, at least half are so poorly known they are almost invisible to any conservation effort - as fewer than 25% of flowering plants have a conservation assessment. In terms of insects, the situation is even worse: with just one million described species out of an estimated 6 million. To put these numbers in context, altogether there are some 36,000 birds, mammals and butterflies – about which much more is known.

We do know that about 40% of all land has been claimed for agriculture, so the assumption is that many plants and insects have already disappeared. But we do not really know. It is estimated because of this that more than half the plants in the world’s collections are mislabelled. Imagine for a moment, how significant that (big number) is. If 50% of plants in collections have an incorrect name, what does that mean for our understanding of one of the biggest living groups on Earth? And what does it mean for conservation?

Plant taxonomy, the approach that could sort this situation, does not fit into the zeitgeist - science by innovation

The fact is, plant taxonomy, the approach that could sort this situation, does not fit into the zeitgeist - science by innovation. There is innovation in plant science. Professor Scotland’s team embraced all the technological advances available, including DNA and phylogenetic trees – earlier this year to create a door-stopping monograph of Ipomoea ‘morning glories’. But the science, the pain-staking taxonomy of identifying and recording many known specimens in a species and creating a monograph, is unadulterated, hard-core botany. It may not be good TV, but it is fundamental and good science.

No Luddite, when walking his dogs, Professor Scotland enjoys using Google Lens to identify UK plants. ‘The app is often right in context of UK plants that are very well known,’ he says, surprised, although pleased to be able to catch it out. But the Professor stands by the science of monography, carefully cataloguing and classifying plants as the most effective way to bring order to the chaos of the botanical world - and make long-term progress.

It is essential, says Professor Scotland, to get to grips with what is there, before it is possible to save it. But at the moment, given a business-as-usual capacity, recent Oxford research has shown it takes about 100 years to discover a plant species, at the most basic level. From collecting the first specimen of a species, to describing it as new, and then gathering 15 correctly-identified specimens of that species, it can take a century.

According to a research paper from a team including Professor Scotland and Dr Zoe Goodwin of Edinburgh, some 40 years is the initial discovery phase – that’s from when the sample is brought in by a plant collector, to when it is identified by a botanist.

But, such is the lack of capacity in the system for taking this further, it can then be another 60 years before the next stage is completed and the 15 samples are gathered, as supporting evidence. It is a tortuous process. It impedes progress and action, but it is essential to identifying species.

What chance of achieving conservation targets, when there is no accurate inventory of plants? What chance can there be of a completed inventory of plants, when it takes 100 years even to reach a basic understanding of a species?

What chance of achieving conservation targets, when there is no accurate inventory of plants? What chance can there be of a completed inventory of plants, when it takes 100 years even to reach a basic understanding of a species? How can this process be speeded up, when there is little interest or support for monographic taxonomy and no coordinated international policy – and half of collections are mislabelled? The task is simply enormous – and that is before we even get to thinking about conservation and biodiversity.

Targets for climate change are clear and comprehensible. But when it comes to plants, the 2010 targets – for instance, to have conservation assessments for all plants by 2020 - were ‘pie in the sky’, according to Professor Scotland, ‘Well-meaning but out of reach’.

He maintains, ‘The most recent high-profile policy suggestion is to simplify the message, as was done for climate change scientists, where the aim is to limit global warming to two degrees C. The suggested unified biodiversity target is to limit species’ extinctions to 20 species per year for the next 50 years.’

But, a clearly exasperated Professor Scotland says, ‘This target is impossible to implement, given the lack of basic knowledge of the world’s biodiversity

When it comes to plants, the 2010 targets...were ‘pie in the sky’, according to Professor Scotland, ‘Well-meaning but out of reach’

In fact, he says, most of the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) international targets, from 2010-2020, ‘were doomed to fail’.

In simple terms, Professor Scotland explains, ‘There is no global strategy for sorting out the taxonomy of flowering plants and insects, so understanding the conservation status of many tropical plants and insects is simply not possible....unless you know what is there, how can you save it or monitor its health?’

Professor Scotland is not recommending an unreconstructed return to Victorian botany as a solution to the world’s problems. But, he insists, it is essential to tackle the huge gaps in knowledge before significant global targets can be made.

Why does it matter?

Clearly a cricket fan, he maintains, ‘Taxonomy is a front foot approach [attempting to tackle the issue, rather than taking a reactive approach]. But we are a very long way from any willingness [internationally] to see something worthwhile in this, despite the evidence.’

Much can be learned from the experience of creating the Ipomoea monograph. Although they were following the path of the first monographer, another Scottish-born Oxford botanist, the celebrated Robert Morison, Professor Scotland and the team confronted the very modern reality of the international plants problem. It was clearly a seminal experience.

It is tempting for the team to reflect that not much has changed in the 300+ years since Morison created the world’s first monograph [of the carrot family]. But taxonomy is in some ways more difficult now than in the past, because of the huge number of specimens that now exist, a voluminous messy literature and many names associated with a group (60-70% of published plant names are usually synonyms). Years of effort was needed to identify the many specimens of Ipomoea in collections around the world - many were synonyms, as the same species had been ‘discovered’ and named multiple times.

If you’re attempting to monitor the health of biodiversity and extinction accurately, you need to know what’s there. We’re never going to get to a comprehensive system where we know everything, but we are a very long way from knowing even half of the world's biodiversity in any detail

Professor Scotland maintains, ‘On the one hand there is a huge diversity of plants, which is a great resource for humankind. But it needs sorting out.

‘On the other hand, if you’re attempting to monitor the health of biodiversity and extinction accurately, you need to know what’s there. We’re never going to get to a comprehensive system where we know everything, but we are a very long way from knowing even half of the world's biodiversity in any detail.’

Goodwin et al 2020 How long does it take to discover a species? Systematics and Biodiversity

Wood et al 2020. A foundation monograph of Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in the New World 2020, PhytoKeys. 10.3897/phytokeys.143.32821

Muñoz-Rodríguez et al 2019. A taxonomic monograph of Ipomoea integrated across phylogenetic scales. Nature Plants 5, 11, 1136-1144. 10.1038/s41477-019-0535-4

- ‹ previous

- 41 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria