Features

Some of the UK's top female scientists will be taking to their soapboxes in Oxford this weekend to share their passion for their subjects with the public.

This Saturday, 18 June, the national Soapbox Science initiative will be making its debut in Oxford. From 2pm to 5pm in Cornmarket Street, 12 female scientists from across the country will be giving a series of fascinating talks on topics as diverse as facial recognition, oral health, the body clock, saving elephants in Mali, and even what tea bags can tell us about soil.

Now in its sixth year, Soapbox Science aims to challenge perceptions of who a scientist is by celebrating the diverse backgrounds of women in science. With speakers ranging from PhD students to professors, Soapbox Science represents the full spectrum of the academic career path and gives the speakers themselves the chance to meet and network with other women in science.

The talks are free and open to the public, and anyone stopping by can expect hands-on props, experiments and specimens, as well as bags of enthusiasm from the speakers.

Carlyn Samuel, ICCS Research Coordinator in the Department of Zoology at Oxford, is coordinating the Oxford leg of Soapbox Science. She said: 'Being part of the great team that has brought Soapbox Science to Oxford for the first time has been an amazing experience. It has opened my eyes to some really interesting research that I would never have heard about otherwise, and I am sure visitors to Cornmarket Street this Saturday will agree.

'Our aim is to bring cutting-edge science to the public in an accessible, fun and unintimidating way. We're hoping to inspire people who never normally get exposed to science – particularly young people. I'm excited that there is such a wide range of topics to learn about, from contentious issues like nuclear energy to saving desert elephants or finding out how chemists have much to learn from nature.'

Among those representing Oxford University on Saturday will be Dr Susan Canney, from the Department of Zoology, whose work involves assessing the threats facing elephants in Mali, and Dr Irina Velsko, from the School of Archaeology, who studies ancient dental calculus and will be talking about how the bacteria that live in our mouths can have a big impact on our overall health.

Soapbox Science co-founder, Dr Nathalie Pettorelli of the Zoological Society of London, said: 'Soapbox Science gives female scientists the much-needed boost to their visibility and profile they need to help achieve equality in science. In the five years of Soapbox, we have seen real impact on the career paths of our speakers, raising their profiles and opening new opportunities for them within the science communities.'

With Johnny Depp’s ‘Mad Hatter’ returning to cinemas in Disney's ‘Through the Looking Glass’, an Oxford academic reveals the real-life influences on Lewis Carroll’s portrayal of insanity and the insane in his Alice books.

Franziska E. Kohlt of the Faculty of English Language and Literature explores Carroll’s knowledge of Victorian psychiatry in the current issue of the Journal of Victorian Culture.

She explains that Carroll’s close relationship with his uncle, Commissioner in Lunacy Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, was his primary connection to the profession. A well-connected barrister, Skeffington was responsible for inspecting lunatic asylums; many of his psychiatric colleagues became friends of Carroll’s too.

Skeffington also had a keen interest in photography, which he passed on to Carroll. It was through this hobby that Carroll came into contact with a friend of his uncle’s, Dr Hugh Welch Diamond of the Surrey lunatic asylum, who believed that photography had an important role to play in diagnosing and recording mental illness. According to contemporary theories, the state of one’s mind was reflected in one’s appearance – which made photographs a highly useful tool.

Ms Kohlt writes: 'Carroll's engagement with Diamond’s work illustrates how the influence of Skeffington and his profession were multifaceted in their nature and consequently found their way into his nephew’s writing via indirect routes. It further indicates how Skeffington’s professional contacts provided Carroll with the opportunity to witness professional practices first hand.'

Through his contacts, Carroll developed an understanding of the practical aspects of psychiatric practice. The Mad Tea-Party in Alice’s Adventures was inspired directly by the tea parties held in asylums as ‘therapeutic entertainments.’ ‘That the types of insanity of the tea-party’s members draw on popular imagery of insanity is made explicit at the earliest instance when the Cheshire Cat informs Alice they are ‘both mad’,’ she writes.

Carroll was also very aware of the class and wealth distinctions between ‘lunatics’ and ‘pauper lunatics,’ which had so much bearing on where and how a Victorian patient was treated. Though never actually referred to in the novel as ‘the mad hatter’, Ms Kohlt feels the character ‘illustrates vividly’ the case of a typical pauper lunatic.

'Carroll's Hatter is consistent with Victorian asylum environments in other aspects, as impoverished hatters and other manual workers and artisans were frequently to be found among a pauper lunatic asylum’s population,' she says.

Ms Kohlt says writers and satirists like Carroll played an important role in raising public awareness of psychiatry. They also shaped the popular image of insanity through their plots and characters.

She says Alice is far more than just a children's novel. 'Alice stands in dialogue with both psychiatric practice and popular perceptions of insanity,' she says.

Follow Franziska Kohlt on Twitter.

We've been able to see them for over a hundred years, but only now are scientists beginning to get to the bottom of what's happening inside membraneless organelles – compartments within cells that really do have no boundaries.

Most people will be broadly familiar with cellular structures such as the nucleus or mitochondria. These compartments, or organelles, are bounded by biological membranes to separate them from the rest of the cell. But, as the name suggests, the droplets of liquid protein known as membraneless organelles have no such physical border, making them an intriguing subject for scientists keen to make use of the advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques that have opened up their inner workings in the past five years.

And now, an Oxford University-led study published in the journal Nature Chemistry has shed new light on the phenomenon, demonstrating that even stable structures such as the DNA double helix can be altered, or 'melted', inside these droplets. That’s in addition to their ability to separate molecules such as proteins that reside within the organelles.

The work also has huge commercial potential, with Oxford's technology transfer company having filed a patent on a technique that could lead to a revolutionary platform for purifying biomolecules in life sciences research.

First author Dr Timothy Nott of Oxford's Department of Chemistry says: 'The premise of our work has been trying to understand how cells are internally compartmentalised. Broadly speaking, there are two ways of creating compartments in cells: one using membranes, which produces things like the nucleus or mitochondria, and another without membranes.

'These membraneless organelles were first observed at the turn of the last century, when experiments involving sea urchin eggs being "squashed" produced globules of liquid that fused together and behaved like an emulsion.

'In the past five years, scientists have realised that advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques can be used to carry out rapid live cell imaging with the aim of interrogating the physical behaviour of these droplets in cells. So only recently have we developed the toolkit necessary to analyse what's going on.'

While there are different classes of membraneless organelles within cells, they all share the common feature of this lack of a delimiting boundary. As well as being tiny and spherical, they also have the viscosity of honey and have been likened to globules of oil in vinegar.

Dr Nott says: 'These unusual properties make membraneless organelles difficult to study. You can't just purify them from within the cell and expect them to behave the same way on the outside.

'What we've been doing is trying to reconstitute them in the lab, controlling when and how they form and performing a wide range of experiments on them.'

The team has been able to identify the main protein components of membraneless organelles – they are made up of long protein chains that 'behave like spaghetti' – which can then be targeted and purified in the lab.

Professor Andrew Baldwin, group leader in Oxford's Department of Chemistry, adds: 'Francis Crick used to say that if you want to study function, study structure. But what we find with membraneless organelles is that while they don't really have a structure, they have plenty of functions.'

Oxford University's technology transfer company is keen to hear from parties interested in developing this innovative technology ([email protected]).

It can take some time before anti-depressant drugs have an effect on people. Yet, the chemical changes that they cause in the brain happen quite rapidly. Understanding this paradox could enable us to create more effective treatments for depression.

In addition to the direct chemical effect, the drug seems to contribute to learning to be in control.

Professor Robin Murphy, Department of Experimental Psychology

However, new research from a group of scientists at Oxford, Harvard and Limerick universities has shown that the way the drugs affect learning about control and helplessness may explain both why anti-depressant effects take time and why their effectiveness differs across individuals.

The team's study saw them administer a commonly prescribed dosage of an anti-depressant drug for 7 days to people who were depressed or not depressed. The drug, escitalopram, increases levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the central nervous system.

After 7 days of either taking the drug or a placebo, volunteers took part in a computer-based game designed to test learning ability. They were required to learn about how their actions could control events occurring in the game. Volunteers tested the effectiveness of their actions on numerous occasions (using keyboard presses) to check if they could control a sound turning on. The researchers had ensured that, in all cases, the volunteers actually had no control over these events in the game.

In these situations, healthy people who are not experiencing depression tend to perceive that they are 'in control', whereas people with depression report little control or so-called helplessness. In this study, published in the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, the team found that the anti-depressant drug affected how people behaved in the game, and importantly how they learned about their own control over events in relation to events randomly occurring in the environment.

People with depression who were taking the placebo tended to interact less with the game and feel that the environment was more in control of events than they were. After taking the drug for 7 days, depressed volunteers interacted more with the game, testing whether their actions controlled the situation on more occasions, and the environment was judged as less controlling than for participants on the placebo. In other words, the drug influenced depressions' effects on learning about control.

Professor Robin Murphy said: 'Other research from members of our group has emphasized the effects these drugs have on processing of emotions, here we focussed on our sense of agency, on how we learn to be 'in control'. In addition to the direct chemical effect, the drug seems to contribute to learning to be in control, less constrained by the environment, and perhaps this might be a link to how these drugs contribute to the alleviation of depression.'

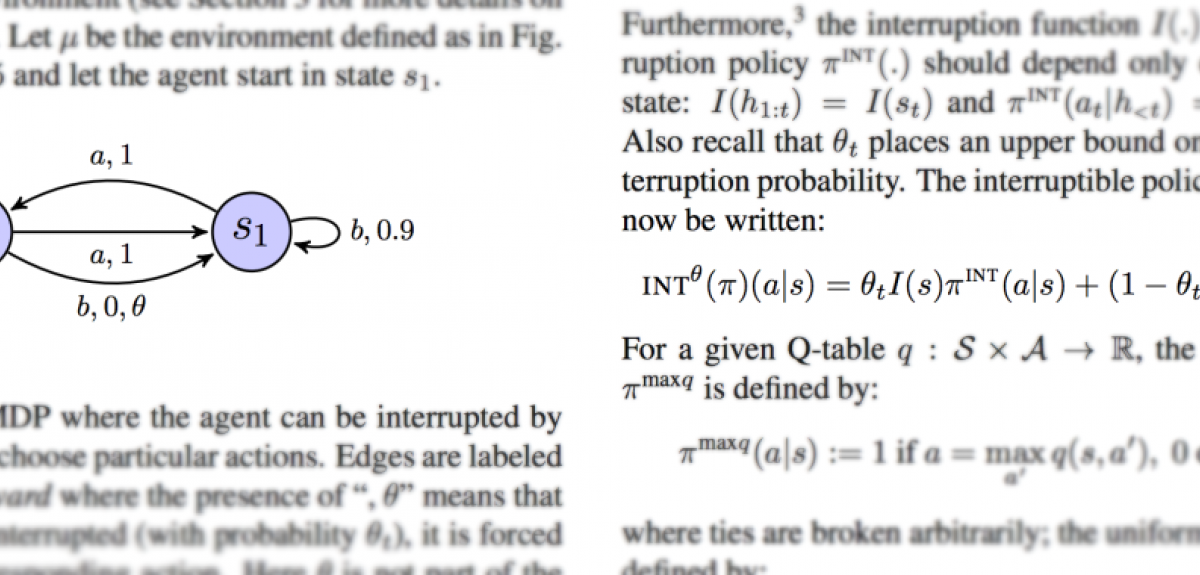

Oxford academics are teaming up with Google DeepMind to make artificial intelligence safer.

Laurent Orseau, of Google DeepMind, and Stuart Armstrong, the Alexander Tamas Fellow in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, will be presenting their research on reinforcement learning agent interruptibility at the Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence conference in New York City later this month.

Orseau and Armstrong's research explores a method to ensure that reinforcement learning agents can be repeatedly safely interrupted by human or automatic overseers. This ensures that the agents do not “learn” about these interruptions, and do not take steps to avoid or manipulate the interruptions.

The researchers say: 'Safe interruptibility can be useful to take control of a robot that is misbehaving… take it out of a delicate situation, or even to temporarily use it to achieve a task it did not learn to perform.'

Laurent Orseau of Google DeepMind says: 'This collaboration is one of the first steps toward AI Safety research, and there's no doubt FHI and Google DeepMind will work again together to make AI safer.'

A more detailed story can be found on the FHI website and the full paper can be downloaded here.

- ‹ previous

- 124 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria