Features

Since late 2015, an epidemic of yellow fever in the central African countries of Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) has affected more than 7,000 people, causing almost 400 deaths.

An international team of researchers led by epidemiologists at Oxford University and Institut Pasteur has sought to better understand the spread of this outbreak, with the aim of making more efficient use of the limited vaccine stocks available.

First author Moritz Kraemer, of Oxford's Department of Zoology, told Science Blog about the study, which is published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases:

'Yellow fever is a haemorrhagic fever transmitted between humans by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, and for a long time it was one of the most feared lethal diseases. In about 15-25% of people infected, it causes severe symptoms that can lead to death. Fortunately, there is a single dose vaccine to protect people for the rest of their lives.

'We analysed datasets describing the epidemic during a large urban yellow fever outbreak in Angola and DR Congo in combination with mosquito-ecological and demographic information. Our aim was to predict the invasion of yellow fever in the region during this outbreak and test whether we could predict where it would arrive next. This was done in light of a shortage in vaccine stock that became apparent during this outbreak in central Africa.

'Early invasion was positively correlated with high population density. The further away locations were from Luanda, the capital of Angola, the later the date of invasion. A model that captured human mobility and vector suitability successfully discriminated districts with high risk of invasion from others at lower risk. If, at the start of the epidemic, sufficient vaccines had been available to target 50 out of 313 districts in the area, our model would have correctly identified 27 (84%) of the 32 districts that were eventually affected. We found that by using a simple statistical model, we could identify locations at highest risk of yellow fever cases.

'From our analysis, we anticipate that the spread of the virus was the result of two factors. One of these was the increased travel between districts – especially large urban centres such as Luanda and Kinshasa, the capital cities of Angola and DR Congo respectively. Such big urban centres are hubs for mosquito activity, and the density of living contributes to the high risk of being infected. In addition, the low levels of vaccination against the virus may have contributed to the successful arrival of the virus in new regions where it had been absent previously.

'The research and model applied here is applicable for a range of diseases, including those rapidly expanding, such as Zika or Ebola. Predicting where the next location may be is important for public health policy makers to decide where to target their resources.

'The continental expansion of Zika in the Americas has shown how quickly new viruses can expand, especially in locations where they have been absent previously. Zika, for example, is also transmitted through the Aedes aegypti mosquito, the same insect that transmits yellow fever. However, in our research we point towards the importance of human demography as a main driver of spread and highlight the possibility that this research could be readily implemented in the context of other vector-borne diseases.'

A gallery of potraits of great Oxford classicists has been installed at the University's Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies.

The portraits, which include Dame Averil Cameron, Gilbert Murray, Anna Morpugo Davies and Sir Fergus Millar, can now be viewed by members of the public in the building on St Giles' in Oxford.

There are images of 32 classicists in total - 28 are photographs and four are oil paintings.

‘These portraits, along with the current exhibition of the Garima Gospels, are part of our aim to brighten up the Classics Faculty’s building and invite people in to look around,’ says Mai Musié of the Classics Faculty.

‘The gallery not only provides a history of Classics at Oxford, but it also celebrates the contributions of many female classical scholars whose work has often not been fully recognised outside their areas of specialism,’ says Professor Fiona Macintosh, Curator of the Ioannou Centre.

A new role has been discovered for a well-known piece of cellular machinery, which could revolutionise the way we understand how tissue is constructed and remodelled within the body.

Lysosomes are small, enzyme-filled sacks found within cells, which break down old cell components and unwanted molecules.

Their potent mixture of destructive enzymes also makes them important in protecting cells against pathogens such as viruses by degrading cell intruders.

However, new research from the University of Oxford has revealed that in addition to breaking down cellular components, lysosomes are also important in building cellular structures.

‘We’ve traditionally viewed lysosomes as the cell ‘dustbin', because everything that goes into them gets chewed up by enzymes,’ said Professor Nigel Emptage from the University’s Department of Pharmacology, who led the research. ‘However, our research has revealed that lysosomes actually play a far more elaborate role, being involved in building as well as demolition, and playing a key part in structural remodelling of cells.'

The discovery was made while the team was looking at hippocampal pyramidal neurones – specialist brain cells important in spatial navigation and memory, which degenerate in Alzheimer's disease. The researchers observed that lysosomes were involved in supporting the growth of spines from dendrites, structures that increase the cell’s ability to store and process large amounts of information.

He added: ‘This discovery fundamentally changes how we view this well-known organelle, as it appears that without them new memory could not be stored in the brain. There has been a growing body of evidence for some time that lysosomes have other functions in addition to their traditional role, but it appears that they are also important in cellular construction.’

The full paper, ‘Activity-Dependent Exocytosis of Lysosomes Regulates the Structural Plasticity of Dendritic Spines’ can be read in the journal Neuron.

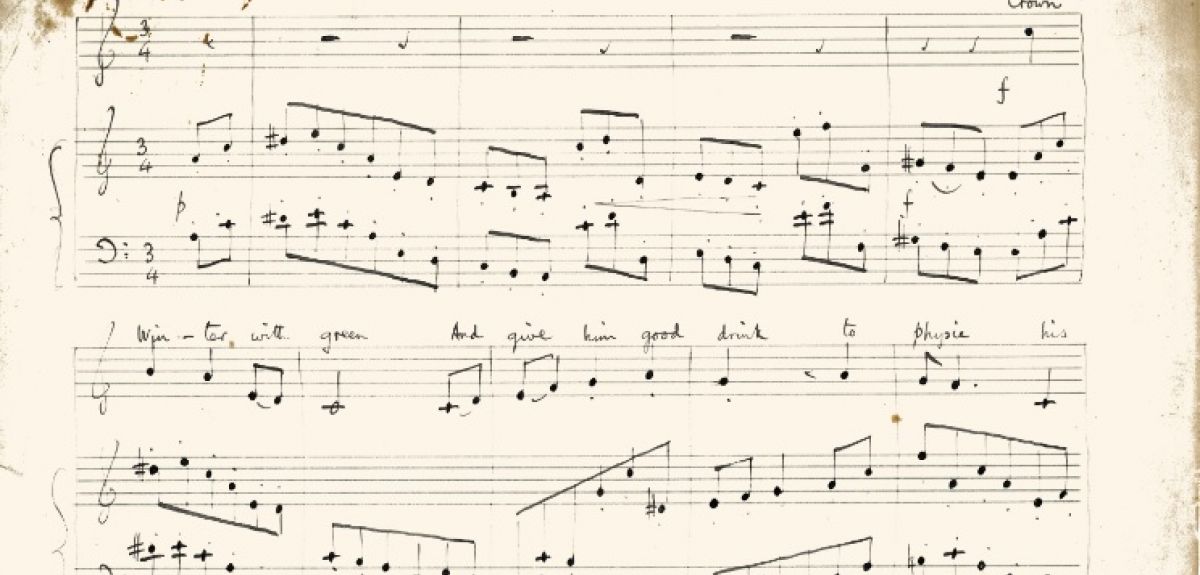

A long-lost song by English composer George Butterworth has been rediscovered at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, a century after his death in the trenches.

The three-page score is a musical setting of a short festive poem by Robert Bridges, beginning with the words Crown winter with green. It is believed to be the only surviving copy of this Butterworth composition.

It was found among a group of uncatalogued music manuscripts which were transferred from the library in Oxford University's Music Faculty to the Bodleian's Weston Library.

The festive find is particularly special because the body of Butterworth’s surviving work is relatively small. Butterworth (1885-1916) was one of the most promising English composers of his generation, but his life was cut short when, at the age of 31, he was killed at the Battle of the Somme in World War I.

Before going off to war he destroyed all of his music which he thought not worthy of preserving. His few surviving works, which include his song settings of AE Housman’s poems from A Shropshire Lad and an orchestral idyll The Banks of Green Willow, are considered masterpieces.

The newly-discovered song has three verses and the lyrics speak of Christmas cheer. It begins with the words ‘Crown winter with green, And give him good drink To physic his spleen …’ and ends with the lines ‘And merry be we This good Yuletide.’ Butterworth’s later music often drew inspiration from English folk music and traditions. He wrote the musical setting for this poem in the style of a drinking song, for voice and piano.

It is not known how the manuscript came to be in the Bodleian Libraries. One possibility is that Butterworth’s father, Sir Alexander Kaye Butterworth, may have passed it on to Sir Hugh Allen, who was a great friend of the composer from his days as an undergraduate at the University of Oxford. Allen was Heather Professor of Music at Oxford from 1918 until his death in 1946, after which his collection of books and music was incorporated into the University’s Music Faculty Library, which is now part of the Bodleian Libraries. It is possible that the song was among these papers but its significance was not noticed at the time.

‘The song’s musical and technical shortcomings suggest that it is probably one of Butterworth’s earlier pieces, possibly dating from his school or student days, which would have been in the early years of the 20th century,’ said Martin Holmes, Alfred Brendel Curator of Music, who rediscovered the manuscript at the Bodleian.

‘As a song, Crown winter with green may not be a masterpiece, in the way that Butterworth’s later Housman songs undoubtedly are, but it can perhaps be seen as a small step on the path towards his musical maturity.'

The manuscript score of Butterworth’s Crown Winter with Green will be on public display in the Bodleian’s Weston Library from Wednesday 14 December to Sunday 18 December, 10am – 5pm (11am-5pm on Sunday). The display will be accompanied by a listening post where visitors can hear a recording of the song.

In a guest blog, Prof Paul Newton of the Nuffield Department of Medicine, and Head of the Medicine Quality Group at the Infectious Diseases Data Observatory (IDDO), explains the history of falsified medicines and highlights what needs to be done to avert a problem that threatens us all.

From Vienna to the Democratic Republic of Congo, fake medicines have threatened citizens across the board – and borders – in wartime as well as peacetime.

Falsified medicines have sadly probably been with us since the first manufacture of medicines and their producers may be the world’s third oldest profession after prostitution and spying. Last year falsified ampicillin was discovered circulating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in bottles of 1,000 capsules and containing no detectable ampicillin.

The post Second World War trade of fake penicillin inspired The Third Man, a fascinating film written by Graham Greene and set in Vienna. Many of the characters, including the protagonist, fake penicillin smuggler Harry Lime, were inspired by real spies and criminals who used penicillin – both falsified and genuine – to bribe, lure and get rich in the chaos of post-war Germany and Austria. Greene later turned the script into a novel.

Unfortunately, the problem is not yet consigned to history. There are probably thousands of Third Men hidden in today’s world, for example, a Parisian who ‘manufactured’ falsified antimalarials containing laxatives, international trade in falsified medicines especially from Asia into Africa, and emergency contraceptives containing antimalarials in South America.

But falsification is not the only problem. There are also severe issues with substandard medicines, poor quality medicines produced due to negligence, sometimes gross, in the manufacturing processes, but not deliberately to defraud patients and health systems. Their consequences are also very harmful; they are likely to be under-recognised drivers of antimicrobial resistance, as they often contain less than the stated amount of active ingredient.

For both falsified and substandard medicines objective prevalence data are few and poor quality, as there has been remarkably little research or surveillance. The data are insufficient to reliably estimate the extent of the problem. Much more investment is needed to understand the epidemiology of poor quality medicines and guide interventions.

Considered a ‘miracle’ medicine, penicillin was highly effective to treat gonorrhoea and syphilis, common venereal diseases among soldiers. During the Second World War and shortly after, the drug supply was controlled by the authorities and primarily reserved for the Army, but as often happens with prohibitions, the illegal trade flourished.

Penicillin was so scarce but so sought after, as an innovative cure of many important bacterial infections, that it became a currency in post-war Europe.

The drug was also at the centre of Operation Claptrap, conducted by US Major Peter Chambers in the first years of the Cold War in Vienna. He offered genuine penicillin to Russian soldiers, in exchange for secrets and defection. It was an attractive offer, as venereal diseases were a court-martial offence in the Red Army.

Austria and France cooperated in 1946 to manufacture penicillin in the Alps to facilitate availability. In 1951, they developed the first oral version of the drug, as Penicillin V. The V referred to vertraulich, the German word for confidential.

In the 21st century, government action remains key to fighting both falsified and substandard medicines. Although there has been an enormous increase in global pharmaceutical manufacturing, there has been a grossly inadequate parallel investment in support for national medicine regulatory authorities (MRAs) in many countries. A key intervention to protect the drug supply in Low- and Middle-Income Countries will be investment in MRAs, the national keystones of medicine regulation.

IDDO works to strengthen knowledge of the scale of the problem of poor quality medicines and the most affected areas, and raise awareness among key stakeholders by sharing global expertise and collating information. The Antimalarial Quality Literature Surveyor, available through the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), is an interactive tool that visualises summaries of published reports of antimalarial medicine quality, displaying their geographical distribution across regions and over time.

The full article, ‘Fake Penicillin, The Third Man and Operation Claptrap’, can be read in the BMJ.

- ‹ previous

- 107 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria