Features

By Shamit Shrivastava and Robin Cleveland

Ultrasound has long been an important tool for medical imaging. Recently, medical researchers have demonstrated that focused ultrasound waves can also improve the delivery of therapeutic agents such as drugs and genetic material. The waves form bubbles that make cell membranes - as well as synthetic membranes enclosing drug-carrying vesicles - more permeable. However, the bubble-membrane interaction is not well understood.

Soft lipid shells, insoluble in water, are a key component of the barrier that surrounds cells. They are also used as drug nanocarriers: nanometer size particles of fat or lipid molecules that carry the drug to be delivered locally at the diseased organ or location, and which can be injected inside the body.

The lipid shell can be “popped” by soundwaves, which can be focused to a spot around the size of a grain of rice, resulting in a highly localized opening of barriers potentially overcoming major challenges in drug delivery.

However, the understanding of such interactions is very limited which is a major hurdle in biomedical applications of ultrasound. Lipid shells can melt from a gel to a fluid-like material depending on environmental conditions.

By observing the nanoscopic changes in lipid shells in real time as they are exposed to soundwaves, our research has shown that lipid shells are easiest to pop when they’re close to melting. We also show that after rupture, a cavity forms and the lipids at the interface experience “evaporative cooling” - the same process by which sweat cools our body - which can locally freeze the lipids, or even water, at the interface. This research advances the fundamental understanding of the interaction of sound waves and lipid shells with applications in drug delivery.

We performed ultrasound experiments on an aqueous solution containing a variety of lipid membranes, which are similar to cellular membranes. We tagged the membranes with fluorescent markers whose light emission provided information about the molecular ordering within the membranes. We then fired ultrasound pulses into the solution and watched for bubbles. The bubbles began to form at lower acoustic energy when the membranes were transitioning from a gel state to a more liquid-like state. The bubbles also lasted longer during this phase transition.

We explained these observed effects with a model that — unlike previous models — account for heat flow between the membranes and the surrounding fluid.

Future work may be able to use this model of membrane thermodynamics to optimize drug-carrying vehicles with membranes that go through a phase transition at the desired moment during an ultrasound procedure.

Read the full study - 'Thermodynamic state of the interface during acoustic cavitation in lipid suspensions' - in Physical Review Materials

Find out more about Dr Shamit Shrivastava

Find out more about Robin O. Cleveland

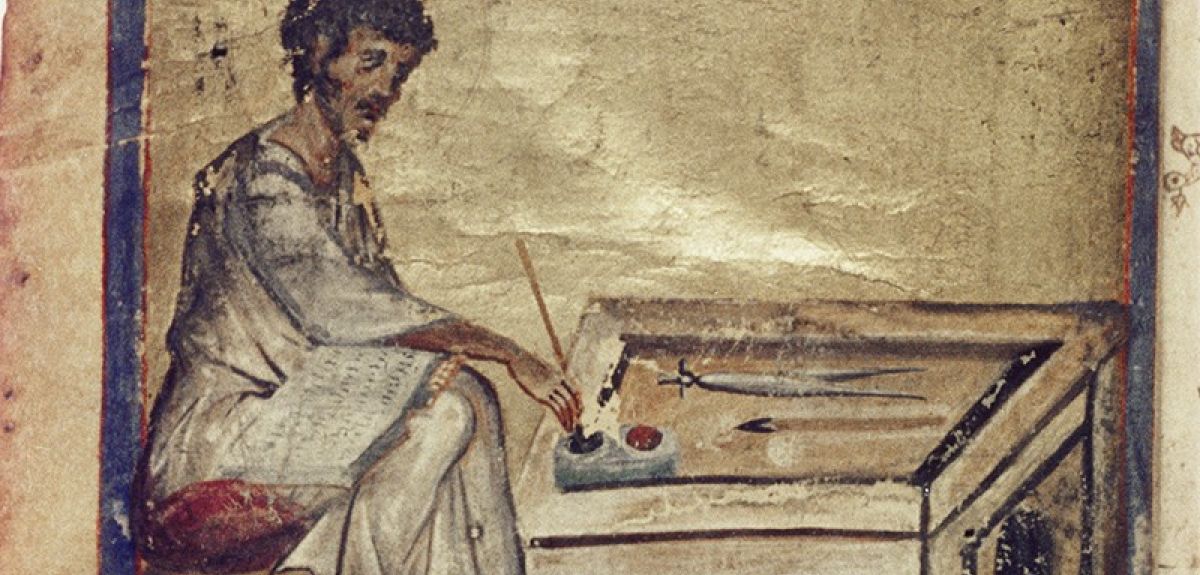

The University of Oxford is delighted to announce a major gift of £3 million from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) to support the consolidation and expansion of Late Antique and Byzantine studies.

SNF’s generous endowment of the prestigious Bywater and Sotheby Professorship of Byzantine and Modern Greek Language and Literature and the Associate Professorship of Byzantine Archaeology and Visual Culture ensures the long-term vitality of teaching and research in Late Antique and Byzantine studies at Oxford.

Additionally, SNF will provide support for the transformation and expansion of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research as a global centre of excellence in Late Antique, Byzantine, and post-Byzantine studies. Over two years, the new SNF grant will build the centre’s capacity with the introduction of a new Directorship, a core administrative operating role, and three graduate scholarships. This will allow the University to set a framework for the expansion of the discipline, while facilitating international engagement with research and teaching institutions and outreach to the wider public.

For more than a millennium, Byzantium sat at the heart of a huge network linking together Asia, Europe, and Africa. Consequently, the study of the Byzantine Empire’s influence in shaping Europe, Russia, and the historic relations between Christianity and Islam has the ability to yield transformative insights into today’s world. However, the area remains under-explored.

Oxford is a world leader in the field of Late Antique and Byzantine studies, which incorporates a range of disciplines, from history and archaeology to languages and theology. The concentration of Byzantine scholars at the University is no accident: the Bodleian Library and Ashmolean Museum house remarkable resources, including many relating to the Byzantine Empire, while Oxford’s excellence in the humanities provides a stimulating cross-disciplinary environment.

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation is a longstanding and generous supporter of the humanities at Oxford. SNF has contributed to the building of the Stelios Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies, and has funded graduate scholarships in Classics and the endowment of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Clarendon Associate Professor and Fellow of Ancient Greek Philosophy, held jointly by the University and Oriel College.

Professor Louise Richardson, Vice Chancellor of the University of Oxford, says: “The Stavros Niarchos Foundation’s generous gift to Late Antique and Byzantine studies will have a tremendous impact on the academic community here in Oxford, in Europe and across the world. We are enormously grateful to the foundation for their support, which will ensure that the field of Late Antique and Byzantine studies continues to thrive for many years to come.”

Professor Peter Frankopan, Director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research, says: “This magnificent gift is testimony to the work done in the field of Late Antique and Byzantine studies at Oxford. It is wonderful that one of the world’s great philanthropic foundations has chosen to support the community of distinguished scholars, early career researchers, graduate and undergraduate students. It sends a powerful message about the importance of the humanities and the role we can play in helping make sense of the past in the fast-moving 21st century.”

Andreas Dracopoulos, Co-President of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, says: “Understanding today’s world requires tracing the dots of history and connecting them through to the present. The Byzantine Empire sat at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa for over a thousand years. As a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, global empire, its legacy on our modern world remains far-reaching and continues to influence cultural and religious practices in Europe, Russia, and beyond. The Stavros Niarchos Foundation is proud to help Late Antique and Byzantine studies at Oxford, and the field as a whole, grow and flourish in the years to come. The grant to secure two important endowed academic positions and fund graduate scholarships is very timely, since support for the humanities in general and Byzantine studies in particular has declined in recent years.”

Cultures and Commemorations of War is an interdisciplinary seminar series that explores the practices and politics of war memory across time. Organised by Dr Alice Kelly, Harmsworth Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Oxford’s Rothermere American Institute, the series was initially funded by a British Academy Rising Stars Engagement Award.

The next event, held on Thursday 9 May, is the fifth in the series and focuses on the interplay between art, war and memory, with a keynote speech from the renowned graphic novelist Joe Sacco. Dr Kelly, who is also a Junior Research Fellow at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, talks to Arts Blog about the event...

What topics will this seminar explore?

The purpose of this interdisciplinary seminar is to explore the artistic and visual representation of war in many different contexts. Over the course of the day, we will hear from a range of academics (from professors to PhD students), artists and practitioners working on the artistic representation and memory of many different conflicts. In the morning there will be short talks on a new First World War video game, on art after Auschwitz, and on the political cartoons of the Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali (assassinated in 1987). In the afternoon we will hear about a project which links the Belgian refugee crisis in the First World War with contemporary refugees, and a project to photograph murals in Northern Ireland through the Troubles.

What role does art play in the representation of war?

Art and war have a complex relationship. In one way, the two are opposite: art is creative, war is destructive, but obviously it’s more complicated than that. Art, perhaps more than other media, has an immediacy which makes it highly effective in telling the story of a war. Art in wartime can promote war through propaganda, or it can protest against war. War inspires art, but it can also be looted in wartime or destroyed by war – think of, in recent times, the temples destroyed in Palmyra, Syria. Art can enable us to remember violence, recording the experience of people who may be forgotten by the historical record, and to rewrite the history of war, but it can also facilitate the forgetting of violence by censorship and photo manipulation. After a war, art can enable people to recover. There are also the complicated ethics of war art – what can be depicted and what can’t? What is reportage and what is exploitation? What constitutes ‘war art’? We’ll be thinking about some of these issues at our seminar.

Tell us about Joe Sacco’s significance in this area.

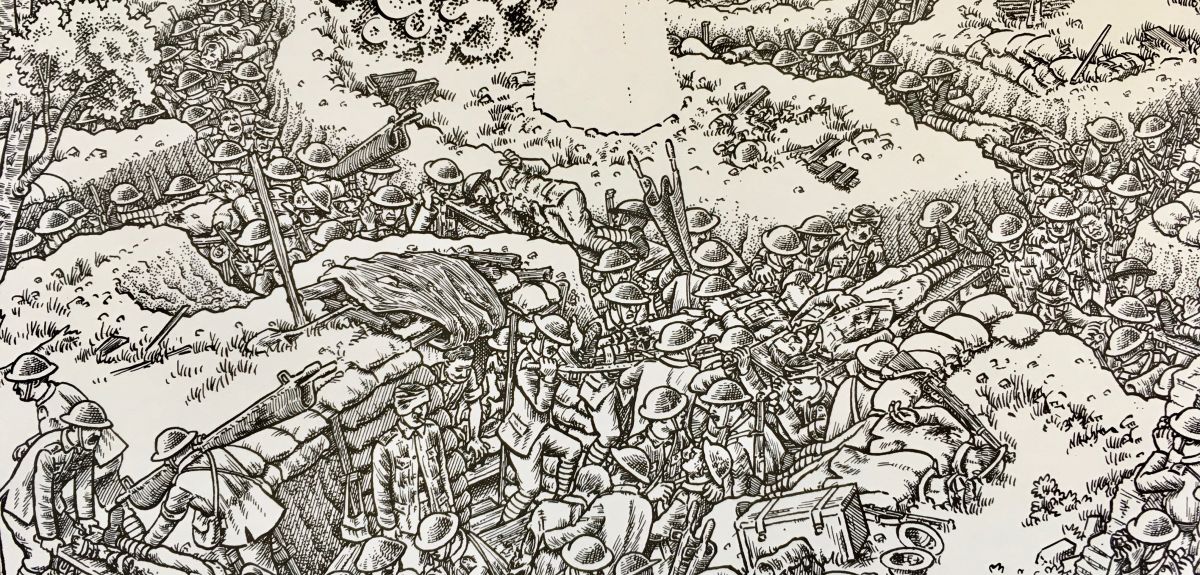

Joe is an award-winning cartoonist who combine eyewitness journalism and art, and is a pioneer within the genre of comics journalism. He is particularly known for representing conflict and violence, and their cultural and social memory. Some of his best-known books, for example Palestine (2001) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009), have focused on the Israel-Palestine conflict, while in books such as Safe Area Goražde he focuses on the Bosnian War. His epic 24-foot depiction of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, called The Great War (2013), should be seen by everyone thinking about the war. The scope of Joe’s reportage and his ability to provide panoramic scenes while paying meticulous attention to detail, combined with his humane and sensitive journalism, constitute a body of work which exemplifies the key themes of this CultCommWar seminar.

What else have you covered in this seminar series?

This is the fifth workshop in the seminar series. Our previous four events have covered a wide range of topics related to the practices and politics of war memory across time. In the first year, the series was funded by a British Academy Rising Stars Public Engagement Fellowship. In the two events held in Oxford and one at Imperial War Museum London, our keynote speakers were the journalist and writer David Rieff, the academic Marita Sturken, and the Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller (who told us about the process of creating We’re Here Because We’re Here, his Somme centenary piece). Our first event this academic year focused on American wars and American memory, and featured the anthropologist Sarah Wagner. Across the series, our conversations have considered the myriad ways that war has been remembered in unofficial and official contexts, from video games to baseball caps (shared between Vietnam vets); from old and new memorials to volunteers dressed as soldiers in Paddington station.

Most of the events feature a morning roundtable led by postgraduates and early career researchers, where the chairs are set in a circle to encourage an open and democratic exchange of ideas. I wanted to move away from the set structure of a conference and I think of these events more like a kind of thinktank, where audience members are encouraged to participate as much as possible.

You can read short pieces about the series on the British Academy website and the Oxford Arts Blog, and I wrote a short article for Times Higher Education on how the series particularly champions emerging and early career scholars in these types of events.

There are still a few places available at the event:

To register for the full-day workshop, please click here.

To register ONLY for the talk by Joe Sacco, please click here.

Eduardo Lalo, Professor of Literature at the Faculty of General Studies at the University of Puerto Rico, and an artist and author, has been appointed as Global South Visiting Fellow at TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities).

Eduardo Lalo's literary oeuvre comprises novels, essays, poetry, graphic art and fascinating hybrids of all of these. He is the author of the novels La inutilidad (Uselessness, 2004), Simone (2015), and Historia de Yuké, which has just been published by Ediciones Corregidor in Argentina. For Simone, he was awarded the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel prize - an exceptional honour granted to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez for One Hundred Years of Solitude (1972) and Roberto Bolaño for The Savage Detectives (1999). Uselessness and Simone have both been translated to English and published by the University of Chicago Press.

The Global South visitor programme, which sits in TORCH, is part of a wider aim to diversify the curriculum in Oxford’s humanities departments. The scheme is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and is part of TORCH’s ‘Humanities & Identities’ series.

Mr Lalo said: ‘I am looking forward to joining the Oxford academic community and working with Dr María del Pilar Blanco from the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages. I am grateful for the opportunity to be included in conversations on curriculum diversification and look forward to sharing my work and experiences with students, academics and staff.’

María del Pilar Blanco, Associate Professor in Spanish American Literature, is sponsoring Mr Lalo’s term at the University. She said: ‘I am pleased to see Eduardo join us here in Oxford. He is one of the most important cultural figures working in Puerto Rico today. He will offer our academic community a much-needed, urgent perspective on contemporary Caribbean arts and politics, as well as a unique view on hemispheric American and transatlantic cultural, political and social exchanges.’

Through the Global South visitor scheme, academics from countries in the Global South are hosted by a University of Oxford academic for one or more terms. The programme also provides role models and increases awareness around diversity and inclusivity across the wider University. The scheme builds on and reinforces existing links between Oxford (including TORCH), Mellon and universities in the Global South.

Mr Lalo will be based at Oxford’s Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and Trinity College during Trinity Term 2019.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) has announced that Caster Semenya and other athletes with disorders of sex (DSD) conditions will have to take testosterone-lowering agents in order to be able to compete. Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Professor of Practical Ethics in Oxford's Faculty of Philosophy, writes in response to this decision...

Reducing the testosterone levels of existing intersex female athletes is unfair and unjust.

The term intersex covers a range of conditions. While intersex athletes have raised levels of testosterone, its effect on individual performance is not clear. Some disorders which cause intersex change the way the body responds to testosterone. For example, in androgen insensitivity syndrome, the testosterone receptor may be functionless or it may be partly functional. In the complete version of the disorder, although there are high levels of testosterone present, it has no effect.

As we don’t know what effect testosterone has for these athletes, setting a maximum level is sketchy because we are largely guessing from physical appearance to what extent it is affecting the body. It is not very scientific. We simply don’t know how much advantage some intersex athletes are getting even from apparently high levels of testosterone.

It is likely that many winners of Olympic medals and holders of world records in the women’s division will have had intersex conditions historically. It is only recently we have become aware of the range of intersex conditions as science has progressed.

These intersex women have been raised as women, treated as women, trained as women. It is unfair to change the rules half way through their career and require them to take testosterone-lowering interventions.

It is a contradiction that doping is banned because it is unnatural, risky to health, and reduces solidarity. But in these cases they want to force a group of women to take unnatural medications, with no medical requirement, in order to alter their natural endowments. Elite sport is all about genetic outliers. Cross-country skier Eero Mantyranta won seven Olympic medals in the 1960s, including three golds. He had a rare genetic mutation that means the body creates more blood cells. The oxygen carrying capacity can be up to 50% more than average. This is a huge genetic advantage for endurance events like cross-country skiing. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) says “the spirit of sport is the celebration of the human spirit, body and mind”, but in this case, the rules seek to limit and quash bodies that don’t fall into line with our expectations.

It is true that the rules of sport are arbitrary. What defines man and woman will always have borderline cases. But it is imperative these individuals are not unfairly disadvantaged. It is unfair to take away a person’s life and career because you choose to redefine the rules.

CAS agreed that the rules are unfair, but found the unfairness justified: “The panel found that the DSD regulations are discriminatory but the majority of the panel found that, on the basis of the evidence submitted by the parties, such discrimination is a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the IAAF’s [International Association of Athletics Federations] aim of preserving the integrity of female athletics in the restricted events.”

Yet there is another option: to implement the rules prospectively by allowing a “grandmother” clause for existing athletes who identify and were raised as women. Then testing for new athletes could take place early – as soon as puberty is complete – to identify athletes who would come under the DSD definition. Affected athletes could make an informed choice about continuing to compete at the cost of being required to take testosterone-lowering agents. This would still deny them the opportunity of competing to their full potential, but it would at least prevent individuals from investing their lives in a sport they would either not want to or be able to compete in.

Intersex conditions can restrict people’s life options. In many cases, it is not possible to have a biologically related child or carry a pregnancy. Unfortunately, it can still carry stigma and discrimination (indeed CAS agree this is an example of it). One possible upside is an advantage in sports. This should not be denied.

Sport is based on natural inequality. If this is of concern to the authorities, I have argued that physiological levels of doping should be allowed. This would allow all women to use testosterone up to 5nmol/L, as can occur naturally in polycystic ovary syndrome and which the IAAF has considered an upper limit for women with intersex conditions. This would also reduce or eliminate the advantage some intersex athletes hold.

The rules of sports are arbitrary but they should not be unfair. Changing the rules to exclude a group of people who signed up under the current rules is unfair. A change for future generations of athletes would be less unfair, but I believe that it will make for a less interesting competition and will still disadvantage some women.

There is no fairytale ending to this story. Someone will be a loser. But that is always the case in sport.

- ‹ previous

- 57 of 253

- next ›

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools