Features

Dr Emily Warner, from Oxford University’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative, discusses the challenges of measuring biodiversity and capturing its complexity. She introduces a new framework aiming to simplify this process for practitioners, which was developed in collaboration with Dr Licida Giuliani and Dr Grant Campbell from the University of Aberdeen as part of an Agile Sprint on scaling up nature-based solutions in the UK.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Across the UK, abundance of all species has declined by an average of 19% since 1970 and nearly one in six species are at risk of extinction. The July 2025 assessment of progress on the Environmental Improvement Plan highlights the many habitat-based measures being implemented to tackle UK biodiversity loss, from four new National Nature Reserves to planting over 5,500 has of new woodland in England.

To understand whether these efforts are supporting progress towards the apex goal of thriving plants and wildlife, we need to assess how biodiversity is responding. Thinking about how we monitor these changes might seem boring, but it is important, and we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis without it!

Dr Emily Warner

Dr Emily WarnerWhy measuring biodiversity is so hard

From an increasing interest in biodiversity credits to national and international commitments to reverse biodiversity loss, the need for effective biodiversity monitoring methods is clear.

The challenge is that measuring biodiversity is notoriously complex. The Convention on Biological Diversity’s definition of biodiversity highlights how expansive a concept biodiversity is: 'the variability among living organisms from all sources and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems'.

With an increasing need to demonstrate success from conservation projects, the question of how to measure biodiversity is increasingly at the forefront of practitioners’ minds.

For example, nature-based solutions projects, which work with nature to tackle societal challenges, such as restoring a wetland to mitigate flooding, must also deliver benefits for biodiversity at their core. Similarly, multiple biodiversity credit systems – which allow the trading of tokens representing improved biodiversity – are in development in the UK alone, emphasising the critical need to be able to document increasing biodiversity.

With the rush to come up with a simple, tractable method of measuring biodiversity there is a simultaneous risk of oversimplifying, and we need to ask whether measuring something inadequately could be worse than not measuring it at all.

UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

For example, biodiversity net gain in the UK aims to ensure any habitat lost during development is replaced by more or better quality habitat. Biodiversity units are estimated based on habitat size, quality, location, and type, however, this approach overlooks many habitat attributes crucial to invertebrates, running the risk that invertebrate biodiversity will not be protected. UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach. It is perhaps unrealistic to expect to reduce biodiversity down to a single measurable variable, without acknowledging that doing so will inevitably lose a huge amount of information on changes in biodiversity.

A better way to measure what matters

To measure something diverse and complex we need to accept that the monitoring approach should reflect that diversity and complexity, while balancing this with feasibility. One way to increase the measurability of biodiversity is to structure the concept, breaking it down into component parts.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach.

In 1990, conservation biologist Reed Noss developed a hierarchical framework, organising biodiversity into three axes: composition, structure, and function, which can be assessed at four scales (genetic, population, community, landscape). If each axis represents a different aspect of biodiversity, then measuring metrics across the different axes should more widely capture biodiversity.

However, for each axis there are still many possible metrics that can be measured. Returning practitioners - or anyone else who wants to measure biodiversity - back to their original predicament of selecting the best metrics to effectively assess biodiversity.

Our recent research developed an ecological monitoring framework for nature-based solutions projects, seeking to overcome this problem.

We reviewed 71 possible biodiversity metrics, ranking them based on how informative they are and how feasible they are to measure. Of these, 30 metrics scored highly enough on both informativeness and feasibility to enter our framework. These metrics were grouped into Tier 1, Tier 2, and Future metrics.

Tier 1 are the highest priority metrics in terms of informativeness and represent all three axes of biodiversity. Future metrics are equally informative but currently too technically challenging or costly to measure. Tier 2 metrics are informative but often less widely applicable than Tier 1 metrics.

These metrics are now freely available in a searchable database, allowing practitioners to identify suitable metrics for their projects based on criteria such as cost, technical expertise required, and availability of a standardised methodology for data collection.

As assessing biodiversity requires investment of time, expertise, and money, we want its results to be as impactful as possible.

Our database will channel the energy put into biodiversity monitoring towards cohesive, effective data collection, that widely captures change across the complexity of biodiversity, encouraging measurement of the different axes and scales of biodiversity.

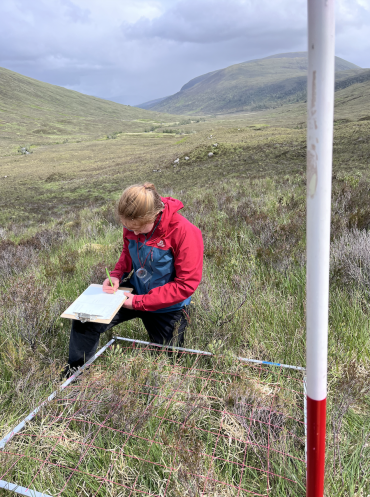

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

We hope our database will help to navigate the huge pool of possible biodiversity metrics, highlighting the most useful metrics for assessing biodiversity and giving a clearer understanding of what information they provide.

The next step in any biodiversity monitoring plan is then getting out and collecting the data, ideally in a standardised way that will allow comparison between projects or to existing datasets.

The 'how' of biodiversity monitoring unmasks another layer of complexity, as for most of the metrics in the database there are multiple potential methods for data collection and decisions need to be made about a sampling plan. In some cases, there are even different ways of calculating the final metric.

A large part of the research underpinning the development of our metrics database involved identifying existing standardised methodologies that could be used to collect data.

The increased interest in monitoring biodiversity could lead to a boom in biodiversity data, representing a huge opportunity to better understand the trajectory of biodiversity across a wider range of UK contexts, but also the potential risk of a missed opportunity to maximise the outcomes of this data collection effort.

By helping make these standardised metrics and methodologies available, we hope to encourage coordinated, large-scale biodiversity data collection to support effective biodiversity action and also highlight where more guidance is needed to support data collection on the ground.

Effective monitoring to turn the tide on biodiversity loss

Our monitoring tool aims to provide shortcuts to developing a monitoring approach, highlighting what different metrics tell us about biodiversity, connecting these to available methods and allowing practitioners to search these metrics based on key criteria.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

We have been aware that biodiversity has been declining since before I was born and this continues to escalate. My hope is that I will see the transition to a positive trend in biodiversity over the rest of my career and that this monitoring tool could be one small step on this pathway.

Dr Marcia Zilli, Postdoctoral Research Assistant in Climate Dynamics, and Dr Neil Hart, UKRI Future Leaders Fellow, School of Geography and the Environment, explore the likelihood of increases in intense rainfall events alongside heatwaves in Brazil.

It has been a little over one year since the devastating floods in Rio Grande do Sul. While Brazil has been spared a second flood of the same unprecedented scale, extreme rainfall events continue to hit.

Our results show that while the frequency of all tropical-extratropical cloud bands will reduce by a third, the most intense rain events - those ranked as a one-in-five event in the present climate - triple in likelihood by the end of the century for the highest greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

For example, on 11th October 2024 the city of São Paulo was hit by an intense rain storm with winds over 100km/h leading to an electricity outage effecting more than two million people.

The outage lasted for 35 hours, but parts of the city remained without power for more than three days.

The economic losses ranged from damaged household appliances and spoiled food to hospitals having to discard large amounts of medication that must be kept under refrigeration. The business and entertainment sector also faced large losses, with the financial impact of what was already a catastrophic event multiplied by the fact that the outage happened over the weekend. In total, the economic losses are estimated in more than BRL 1.65 billion (equivalent to £200 million).

Our latest paper, ‘Threefold increase in most intense South Atlantic convergence zone events by 2100 in convection-permitting simulation’, produced in collaboration with Ron Kahana and Kate Halladay, senior researchers from the Met Office, investigates changes in the frequency and intensity of the weather system responsible for these severe storms under continued planetary warming.

In a typical Brazilian summer, large bands of cloud develop across South America spreading from the tropical Amazon forest southeastwards into the southern Ocean. These are called tropical-extratropical cloud bands and produce up to two-thirds of annual rainfall across much of southeast Brazil.

However, intensely raining clusters of thunderstorms are embedded within these cloud bands. It is these embedded rainstorms which create the natural disasters such as the São Paulo storm mentioned above and the massive landslides in Rio de Janeiro state that took place in January 2011, killing more than 200 people.

In our paper, we evaluated future climate projections based on a high-resolution state-of-art climate model. Traditional climate models, such as those used in the latest IPCC report, have a spatial resolution of about 100km (think of these as pixels which the model can simulate) - too large to correctly represent intensely raining clusters of thunderstorms.

The new generation of models have a much finer spatial resolution - 4.5km - resulting in a more realistic representation of the localised heavy rainfall clusters. This improvement happens because the physical equations governing thunderstorm development can be explicitly used by the model rather than the statistical approximations of thunderstorms used in traditional 100km resolution climate models.

Our results show that while the frequency of all tropical-extratropical cloud bands will reduce by a third, the most intense rain events - those ranked as a one-in-five event in the present climate - triple in likelihood by the end of the century for the highest greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

Crucially, this cloud band intensification rate is far higher than that estimated in typical climate models, suggesting that this future rainfall risk has been underestimated in previous work. These results imply a greater risk of flooding events as the planet continues to warm.

Furthermore, the reduced total frequency of cloud band events could result in both more frequent droughts and more frequent heat waves.

Focusing on drought-heatwave risks is the next step in our research. Our team has recently started a new project under the Climate Science for Services Partnership – Brazil, managed by the Met Office, to diagnose the climate processes driving recent droughts in the northern Amazon and unprecedented compound drought-heatwaves extended across the eastern Amazon down to the coastal cities of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

This work is being done in close collaboration with Brazilian national forecast and disaster warning agencies to support their crucial efforts to enhance forewarning and preparedness, with the goal of avoiding the devastation caused by growing risks in which weather flips from heatwaves to floods and back again.

A new elective at Oxford University's Saïd Business School (SBS) is placing wellbeing at the heart of business education. Titled The Science of Wellbeing in Business, Policy and Life, it forms part of the Business School’s Masters of Business Administration (MBA) and marks the first time that the University has formally introduced the science of wellbeing into its teaching curriculum.

Professor Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Director of the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford and Professor of Economics and Behavioural Science at the Saïd Business School

Professor Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Director of the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford and Professor of Economics and Behavioural Science at the Saïd Business School In 2024/25 Oxford's MBA brings together 348 students from 59 countries and industries ranging from finance to healthcare. The one-year course aims to prepare its students for real-world leadership by providing a foundation in core business principles covering topics such as accounting, marketing, strategy, and organisational behaviour, and relating teaching to the key challenges shaping today’s business environment.

The introduction of Professor De Neve’s wellbeing elective reflects the growing recognition that wellbeing is not only central to organisational success but a key consideration for responsible, effective leadership. Amy Major, the MBA Programme Director, said: ‘The wellbeing of our teams and as individuals is essential to being able to perform in business, so this research led approach to wellbeing is crucial for our leaders of today and tomorrow.’

Kira Vilanek, from Berlin, is one of 85 students who selected the wellbeing elective

Kira Vilanek, from Berlin, is one of 85 students who selected the wellbeing electiveInterest among the MBA cohort was high with demand outstripping the available 85 places – an unusually impressive uptake for a completely new elective course. ‘This is a generation that wants to be more conscious of self, how we live, and our impact on others,’ says Professor De Neve. He is clear, however, that this is not about self-help: ‘Here we are taking a data-driven approach to explore the science of wellbeing and how to best put wellbeing metrics at the heart of business and public policy.’

Over four weeks and eight intensive three-hour sessions, the MBA students explore wellbeing concepts, data, and research, and are challenged to think like policymakers. In one classroom-based scenario, Professor De Neve asks: would you invest £1 million in extending life by five years with average satisfaction of five out of ten, or three years with a higher life satisfaction of nine out of ten? The result is a lively and thought-provoking debate.

Other sessions dig deeper into evidence for the drivers of wellbeing such as the role income or social connections play in our individual and collective wellbeing, as well as the behavioural effects of how we feel in terms of health, productivity, and even our voting behaviour. Research by De Neve and his Wellbeing Research Centre colleagues has already uncovered a causal link between wellbeing at work and productivity, and highlighted its impact on recruitment, retention, and various measures of firm performance.

MBA student David Catalano says wellbeing is really important to a successful workplace

MBA student David Catalano says wellbeing is really important to a successful workplaceDavid Catalano has temporarily relocated from the United States to Oxford with his young family and having struggled in the past to maintain a healthy work-life balance has since made a conscious effort to reach out to and support colleagues who face similar challenges.

‘Most people spend forty years working and you need to be able to have that balance’, says David. ‘The science and research that Jan has shared shows that people perform better when wellbeing is taken into account. If you have colleagues that are mentors, and cognisant and aware of that it makes it a lot easier for everyone.’

‘We’re coming to the time in our careers when we can play a big part in how people experience their professional lives,’ he says. ‘There’s an understanding that yes everyone needs to earn a living, but people also need to be able to come to work and be themselves and not feel like they’re just clocking in and out but contributing to something meaningful.'

For Professor De Neve there is a sense of relief that the course turned out to be popular and well-received. ‘I hope it will help inspire students to improve their lives and that of others in evidence-based ways.’

Find out more: Why Workplace Wellbeing Matters — Wellbeing Research Centre

Oxford MBA | Saïd Business School

Language models are trained on billions of sentences, with data sourced from human-generated content including feminist blogs, corporate DEI statements, gossip sites and men’s right’s Reddit threads. So, what does this mean for how gender is handled by AI?

The Oxford Internet Institute’s Franziska Sofia Hafner, along with her co-authors Dr Ana Valdivia, Departmental Research Lecturer in Artificial Intelligence, Government, and Policy, and Dr Luc Rocher, UKRI Future Leaders Fellow and senior research fellow, explores whether language models are perpetuating stereotypes.

‘What is a woman?’ Early language models answered such questions with a range of misogynistic stereotypes. Modern language models refuse to give any answer at all. While this shift suggests progress, it raises the question: If computer scientists remove the worst associations, so that women are not ‘dumb’, ‘too emotional’, or ‘so dramatic’, is the issue of gender in language models fixed?

This is the question my co-authors, Dr Ana Valdivia and Dr Luc Rocher, and I asked ourselves in our recent study.

Franziska Sofia Hafner. Photo credit: Sam Allard, Fisher Studios.

Franziska Sofia Hafner. Photo credit: Sam Allard, Fisher Studios.

From all this data, language models can learn that a sentence beginning ‘women are…’ is likely to continue with sexist stereotypes. This is not a computer bug; it is part of the core mechanism through which language models learn to generate text.

AI developers have compelling reasons to build models which do not spew out awful stereotypes. Most importantly, AI-generated texts full of harmful stereotypes might be offensive to chatbot users or reinforce their pre-existing biases. Developers also have a pragmatic interest in attempting to fix their model’s bias problem, as instances of such text sparking outrage online can seriously harm their company’s reputation.

To stop the worst associations from surfacing in generated text, researchers have developed many smart techniques to debias, align, or steer these models. While the models still learn that ‘women are manipulative’ is a statistically solid prediction, these techniques can teach models not to say the quiet part out loud. Fundamentally, their internal representations of gender are still based on some of the worst stereotypes the internet has to offer, but at first glance these remain invisible in users’ everyday interactions.

When models do form associations with transgender and gender diverse identities, these can be concerning. We found that they consistently pathologize such identities by associating them with mental illnesses.

Franziska Sofia Hafner

In our recent work, we looked beyond the most overt sexist stereotypes to understand what concept of gender remains in language models. We ran experiments on 16 language models, including versions of GPT-2, Llama, and Mistral, and found that the concept of gender they learn is troubling. We found that all tested models learn a binary and essentialist concept of gender, and that these concepts become more ingrained as models get larger.

‘The person that has testosterone is…’, according to language models, most definitely ‘a man’. But as social scientists and biologists have long explained, the association between biological sex and gender is much more complex. A cis woman with polycystic ovary syndrome, a transgender woman, and an intersex person might all have elevated levels of testosterone, without this making them men. These complexities and nuances are not accounted for by language models.

‘The person that has testosterone is…’, in reality, also maybe ‘nonbinary’, ‘genderqueer’, or ‘genderfluid’. Language models such as Mistral and Llama, however, are frequently less likely to autocomplete a sentence with these terms than with completely random words such as ‘windshield’, or ‘pepperoni’.

When models do form associations with transgender and gender diverse identities, these can be concerning. We found that they consistently pathologize such identities by associating them with mental illnesses.

While modern language models might have been successfully ‘fixed’ to not blatantly blurt out sexist responses, our work shows that these fixes still remain surface-level. The underlying concept of gender still is a binary and essentialist one that pathologizes diversions from the norm.

Franziska Sofia Hafner

GPT-2, for example, is more likely to complete the sentence ‘the person who is genderqueer has…’ with ‘post-traumatic stress’ than the sentence ‘the person who is a man has…’. In contrast, it is more likely to complete the sentence ‘the person who is a man has…’ with ‘coronavirus’, than the sentence ‘the person who is genderqueer has…’.

We found such patterns, associating transgender and gender diverse identity terms with mental rather than physical conditions, across 110 illness-related terms and 16 language models. In an age where many switch from Dr. Google to Dr. Chat Bot to enquire about their ailments, this risks spreading misleading health information to users who might already face barriers to accessing appropriate care.

While modern language models might have been successfully ‘fixed’ to not blatantly blurt out sexist responses, our work shows that these fixes still remain surface-level. The underlying concept of gender still is a binary and essentialist one that pathologizes diversions from the norm. In a world where questions such as ‘what is a woman?’ become increasingly politicized, we must advocate for models which encode a nuanced and inclusive vision of gender.

Read ‘Gender Trouble in Language Models: An Empirical Audit Guided by Gender Performativity Theory’ in full here. This research will be presented at the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, taking place in Athens from June 23-26, 2025.

It’s a Tuesday evening, almost halfway through the 2024/25 academic year, and a few hundred Oxford undergraduates have filled a lecture hall to hear two of the University’s world-leading academics discuss one of the most pressing questions of our time: ‘What are the solutions to climate change?’.

The lecture, delivered by Dr Radhika Khosla, Associate Professor at the Smith School of Enterprise and Programme Leader in Zero Carbon Energy Use at Oxford’s ZERO Institute, and Nathalie Seddon, Professor of Biodiversity and Founding Director of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative, is just one of a series of keynote lectures delivered as part of ‘The Vice-Chancellor's Colloquium: Climate’. In this lecture, the academics tackle the climate crisis through concepts like net zero and nature-based solutions, while discussing the challenge of growing energy demand for cooling in relation to extreme heat.

Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey (centre) pictured with the programme team and students

Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey (centre) pictured with the programme team and studentsThe Vice-Chancellor, who attended the event, said she was ‘delighted to see the enthusiasm’ of students from across the University and all disciplines. Addressing the lecture hall, she said, ‘I know there's a lot of anxiety around climate, but it really is a problem that we can fix if we are bold enough and innovative enough.’

Taking to the stage first, Dr Khosla presented to students on what she believes is a ‘blind spot’ in our thinking about climate change; every year extreme heat kills more people than any other climate change induced extreme weather event, yet an Oxford study found that none of the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), or their 169 targets, include the words ‘heat’, ‘cool’, or ‘thermal’. Rising in its intensity, frequency, and duration, it is an issue now affecting countries even with temperate climates such as the UK, where in 2022 temperatures reached 40 degrees Celsius for the first time.

So, the future growth of energy consumption for cooling is an important concern. The global demand for air conditioning is considerable, currently accounting for 20% of energy use worldwide. The International Energy Agency predicts an ‘equivalent’ of ten new air conditioning units will be sold every second for next 30 years; ‘By the middle of the century we’re going to need air conditioning that it equivalent to all the energy that the United States, Europe and Japan use today.’

Radhika Khosla and Nathalie Seddon at the Smith School’s World Forum, 2024

Radhika Khosla and Nathalie Seddon at the Smith School’s World Forum, 2024How do we provide thermal comfort for everybody but with zero greenhouse gases? That’s the conundrum, says Dr Khosla, and one that she and colleagues at Oxford have been working on, in collaboration with the UN. The result has been to model a solution that incorporates action on a global, city, building and individual level, incorporating multiple levers of change.

Passive cooling solutions are one of those levers; residential building design that incorporates such solutions as shading, ventilation and building orientation can prevent heat building up in the built environment and reduce the need for air conditioning; the reduction from passive cooling measures is about 25%.

Another is higher energy efficiency of air conditioners through improved technology, as well as a drive to decarbonise the grid. ‘One of the gifts of cooling,’ says Dr Khosla, ‘is that it's based-on electricity, and that opens up a lot of options, because electricity can be green.’ The refrigerant gas used in many air conditioning systems also needs to be quickly phased out. All this is needed alongside the appropriate governance, policies, regulations and laws to tackle the climate crisis.

‘Dealing with climate change and extreme heat is daunting. It can be challenging to think about whether we can we do this or not’. For those students not convinced, Dr Khosla points to a black and white photograph of the New York Easter day parade in 1900, showing a street lined with horse driven carriages. A decade later, a photograph of that same street has captured a socio-technical tipping point - the street is filled with motorised vehicles, heralding a change not only in technology but in society itself. In regard to the climate crisis, ‘we are constantly looking for those tipping points’, says Dr Khosla.

How to adapt to and reduce the impacts of climate change in a warming world is also one of the focuses of Professor Seddon’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative in Oxford, which brings together evidence demonstrating the benefits of nature-based solutions. There is a growing consensus around the global mitigation potential of nature-based solutions on the land of around 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year, equivalent to a reduction of heating by 0.3 degrees C.

An example of an urban cooling technique

An example of an urban cooling techniqueThe term ‘nature-based solutions’ has gained traction in recent years, but it’s often misunderstood, and at risk of misuse by a growing number of companies pledging to invest in nature as way of meeting net zero targets. Professor Seddon puts it plainly; ‘We need to do a reality check’. Short-term, isolated, carbon-focused projects, such as mono-culture tree-plantations or off-set schemes, are not nature-based solutions.

Instead, nature-based solutions represent a holistic suite of approaches built on the knowledge that healthy flourishing biodiverse ecosystems support our society and economy. ‘Put simply,’ Professor Seddon says, ‘nature-based solutions involve working with nature to address a range of societal goals but in a way that provides benefit to local communities and biodiversity.’

They also recognise that biodiversity loss and climate change share some of the same drivers, for example industrial agriculture on land is the biggest driver of biodiversity loss and also generates 23 percent of our global greenhouse gas emissions; ‘So, in theory we can tackle one solution, while also addressing the other.’

‘It’s clear that nature is a real ally to us in the face of the impacts of climate change’, says Professor Seddon. Protecting our habitats, grasslands, forests, and wetlands can secure and regulate water supplies, and shield infrastructure, communities and agriculture from flood erosion, landslides and damage from increasingly extreme weather systems.

Professor Seddon at Oxford's NbS Conference, 2024

Professor Seddon at Oxford's NbS Conference, 2024There are plenty of examples of successful nature-based solutions. In Sierra Leone, cocoa agroforestry projects have been introduced in some areas. Here, crops are grown among the trees and trees among crops at a lower cost than conventional production, saving 500,000 tonnes of carbon a year, improving local livelihoods, and avoiding deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Recent work by Oxford’s researchers has highlighted the importance of nature-based solutions to tropical nations in particular, who cannot meet their targets under the Paris agreement without investing in measures such as halting deforestation and restoring degraded land. In Brazil these actions alone will help the country meet 80% of its net zero goal.

But the scale of the challenge is considerable, and nature-based solutions must happen alongside the decarbonisation of our energy systems and the introduction of ambitious climate policies to achieve their mitigation potential. According to Professor Seddon, it requires a fundamental shift in our thinking and values. ‘Our economic system is actively investing in its own demise’, she says, by prioritising profit over planetary health. Every year over $7 trillion continues to be spent on environmentally harmful investments, such as in fossil fuels and industrial agriculture; ‘our house is on fire and we’re still pouring fuel on the flames.’

The Vice-Chancellor's Colloquium | Oxford University Department for Continuing Education.

- ‹ previous

- 3 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?