Features

Dr Emily Warner, from Oxford University’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative, discusses the challenges of measuring biodiversity and capturing its complexity. She introduces a new framework aiming to simplify this process for practitioners, which was developed in collaboration with Dr Licida Giuliani and Dr Grant Campbell from the University of Aberdeen as part of an Agile Sprint on scaling up nature-based solutions in the UK.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Across the UK, abundance of all species has declined by an average of 19% since 1970 and nearly one in six species are at risk of extinction. The July 2025 assessment of progress on the Environmental Improvement Plan highlights the many habitat-based measures being implemented to tackle UK biodiversity loss, from four new National Nature Reserves to planting over 5,500 has of new woodland in England.

To understand whether these efforts are supporting progress towards the apex goal of thriving plants and wildlife, we need to assess how biodiversity is responding. Thinking about how we monitor these changes might seem boring, but it is important, and we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis without it!

Dr Emily Warner

Dr Emily WarnerWhy measuring biodiversity is so hard

From an increasing interest in biodiversity credits to national and international commitments to reverse biodiversity loss, the need for effective biodiversity monitoring methods is clear.

The challenge is that measuring biodiversity is notoriously complex. The Convention on Biological Diversity’s definition of biodiversity highlights how expansive a concept biodiversity is: 'the variability among living organisms from all sources and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems'.

With an increasing need to demonstrate success from conservation projects, the question of how to measure biodiversity is increasingly at the forefront of practitioners’ minds.

For example, nature-based solutions projects, which work with nature to tackle societal challenges, such as restoring a wetland to mitigate flooding, must also deliver benefits for biodiversity at their core. Similarly, multiple biodiversity credit systems – which allow the trading of tokens representing improved biodiversity – are in development in the UK alone, emphasising the critical need to be able to document increasing biodiversity.

With the rush to come up with a simple, tractable method of measuring biodiversity there is a simultaneous risk of oversimplifying, and we need to ask whether measuring something inadequately could be worse than not measuring it at all.

UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

For example, biodiversity net gain in the UK aims to ensure any habitat lost during development is replaced by more or better quality habitat. Biodiversity units are estimated based on habitat size, quality, location, and type, however, this approach overlooks many habitat attributes crucial to invertebrates, running the risk that invertebrate biodiversity will not be protected. UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach. It is perhaps unrealistic to expect to reduce biodiversity down to a single measurable variable, without acknowledging that doing so will inevitably lose a huge amount of information on changes in biodiversity.

A better way to measure what matters

To measure something diverse and complex we need to accept that the monitoring approach should reflect that diversity and complexity, while balancing this with feasibility. One way to increase the measurability of biodiversity is to structure the concept, breaking it down into component parts.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach.

In 1990, conservation biologist Reed Noss developed a hierarchical framework, organising biodiversity into three axes: composition, structure, and function, which can be assessed at four scales (genetic, population, community, landscape). If each axis represents a different aspect of biodiversity, then measuring metrics across the different axes should more widely capture biodiversity.

However, for each axis there are still many possible metrics that can be measured. Returning practitioners - or anyone else who wants to measure biodiversity - back to their original predicament of selecting the best metrics to effectively assess biodiversity.

Our recent research developed an ecological monitoring framework for nature-based solutions projects, seeking to overcome this problem.

We reviewed 71 possible biodiversity metrics, ranking them based on how informative they are and how feasible they are to measure. Of these, 30 metrics scored highly enough on both informativeness and feasibility to enter our framework. These metrics were grouped into Tier 1, Tier 2, and Future metrics.

Tier 1 are the highest priority metrics in terms of informativeness and represent all three axes of biodiversity. Future metrics are equally informative but currently too technically challenging or costly to measure. Tier 2 metrics are informative but often less widely applicable than Tier 1 metrics.

These metrics are now freely available in a searchable database, allowing practitioners to identify suitable metrics for their projects based on criteria such as cost, technical expertise required, and availability of a standardised methodology for data collection.

As assessing biodiversity requires investment of time, expertise, and money, we want its results to be as impactful as possible.

Our database will channel the energy put into biodiversity monitoring towards cohesive, effective data collection, that widely captures change across the complexity of biodiversity, encouraging measurement of the different axes and scales of biodiversity.

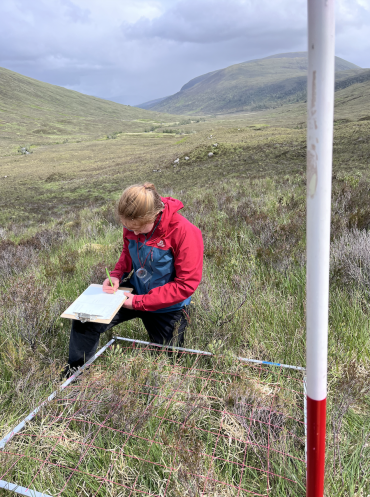

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

We hope our database will help to navigate the huge pool of possible biodiversity metrics, highlighting the most useful metrics for assessing biodiversity and giving a clearer understanding of what information they provide.

The next step in any biodiversity monitoring plan is then getting out and collecting the data, ideally in a standardised way that will allow comparison between projects or to existing datasets.

The 'how' of biodiversity monitoring unmasks another layer of complexity, as for most of the metrics in the database there are multiple potential methods for data collection and decisions need to be made about a sampling plan. In some cases, there are even different ways of calculating the final metric.

A large part of the research underpinning the development of our metrics database involved identifying existing standardised methodologies that could be used to collect data.

The increased interest in monitoring biodiversity could lead to a boom in biodiversity data, representing a huge opportunity to better understand the trajectory of biodiversity across a wider range of UK contexts, but also the potential risk of a missed opportunity to maximise the outcomes of this data collection effort.

By helping make these standardised metrics and methodologies available, we hope to encourage coordinated, large-scale biodiversity data collection to support effective biodiversity action and also highlight where more guidance is needed to support data collection on the ground.

Effective monitoring to turn the tide on biodiversity loss

Our monitoring tool aims to provide shortcuts to developing a monitoring approach, highlighting what different metrics tell us about biodiversity, connecting these to available methods and allowing practitioners to search these metrics based on key criteria.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

We have been aware that biodiversity has been declining since before I was born and this continues to escalate. My hope is that I will see the transition to a positive trend in biodiversity over the rest of my career and that this monitoring tool could be one small step on this pathway.

It’s a Tuesday evening, almost halfway through the 2024/25 academic year, and a few hundred Oxford undergraduates have filled a lecture hall to hear two of the University’s world-leading academics discuss one of the most pressing questions of our time: ‘What are the solutions to climate change?’.

The lecture, delivered by Dr Radhika Khosla, Associate Professor at the Smith School of Enterprise and Programme Leader in Zero Carbon Energy Use at Oxford’s ZERO Institute, and Nathalie Seddon, Professor of Biodiversity and Founding Director of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative, is just one of a series of keynote lectures delivered as part of ‘The Vice-Chancellor's Colloquium: Climate’. In this lecture, the academics tackle the climate crisis through concepts like net zero and nature-based solutions, while discussing the challenge of growing energy demand for cooling in relation to extreme heat.

Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey (centre) pictured with the programme team and students

Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey (centre) pictured with the programme team and studentsThe Vice-Chancellor, who attended the event, said she was ‘delighted to see the enthusiasm’ of students from across the University and all disciplines. Addressing the lecture hall, she said, ‘I know there's a lot of anxiety around climate, but it really is a problem that we can fix if we are bold enough and innovative enough.’

Taking to the stage first, Dr Khosla presented to students on what she believes is a ‘blind spot’ in our thinking about climate change; every year extreme heat kills more people than any other climate change induced extreme weather event, yet an Oxford study found that none of the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), or their 169 targets, include the words ‘heat’, ‘cool’, or ‘thermal’. Rising in its intensity, frequency, and duration, it is an issue now affecting countries even with temperate climates such as the UK, where in 2022 temperatures reached 40 degrees Celsius for the first time.

So, the future growth of energy consumption for cooling is an important concern. The global demand for air conditioning is considerable, currently accounting for 20% of energy use worldwide. The International Energy Agency predicts an ‘equivalent’ of ten new air conditioning units will be sold every second for next 30 years; ‘By the middle of the century we’re going to need air conditioning that it equivalent to all the energy that the United States, Europe and Japan use today.’

Radhika Khosla and Nathalie Seddon at the Smith School’s World Forum, 2024

Radhika Khosla and Nathalie Seddon at the Smith School’s World Forum, 2024How do we provide thermal comfort for everybody but with zero greenhouse gases? That’s the conundrum, says Dr Khosla, and one that she and colleagues at Oxford have been working on, in collaboration with the UN. The result has been to model a solution that incorporates action on a global, city, building and individual level, incorporating multiple levers of change.

Passive cooling solutions are one of those levers; residential building design that incorporates such solutions as shading, ventilation and building orientation can prevent heat building up in the built environment and reduce the need for air conditioning; the reduction from passive cooling measures is about 25%.

Another is higher energy efficiency of air conditioners through improved technology, as well as a drive to decarbonise the grid. ‘One of the gifts of cooling,’ says Dr Khosla, ‘is that it's based-on electricity, and that opens up a lot of options, because electricity can be green.’ The refrigerant gas used in many air conditioning systems also needs to be quickly phased out. All this is needed alongside the appropriate governance, policies, regulations and laws to tackle the climate crisis.

‘Dealing with climate change and extreme heat is daunting. It can be challenging to think about whether we can we do this or not’. For those students not convinced, Dr Khosla points to a black and white photograph of the New York Easter day parade in 1900, showing a street lined with horse driven carriages. A decade later, a photograph of that same street has captured a socio-technical tipping point - the street is filled with motorised vehicles, heralding a change not only in technology but in society itself. In regard to the climate crisis, ‘we are constantly looking for those tipping points’, says Dr Khosla.

How to adapt to and reduce the impacts of climate change in a warming world is also one of the focuses of Professor Seddon’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative in Oxford, which brings together evidence demonstrating the benefits of nature-based solutions. There is a growing consensus around the global mitigation potential of nature-based solutions on the land of around 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year, equivalent to a reduction of heating by 0.3 degrees C.

An example of an urban cooling technique

An example of an urban cooling techniqueThe term ‘nature-based solutions’ has gained traction in recent years, but it’s often misunderstood, and at risk of misuse by a growing number of companies pledging to invest in nature as way of meeting net zero targets. Professor Seddon puts it plainly; ‘We need to do a reality check’. Short-term, isolated, carbon-focused projects, such as mono-culture tree-plantations or off-set schemes, are not nature-based solutions.

Instead, nature-based solutions represent a holistic suite of approaches built on the knowledge that healthy flourishing biodiverse ecosystems support our society and economy. ‘Put simply,’ Professor Seddon says, ‘nature-based solutions involve working with nature to address a range of societal goals but in a way that provides benefit to local communities and biodiversity.’

They also recognise that biodiversity loss and climate change share some of the same drivers, for example industrial agriculture on land is the biggest driver of biodiversity loss and also generates 23 percent of our global greenhouse gas emissions; ‘So, in theory we can tackle one solution, while also addressing the other.’

‘It’s clear that nature is a real ally to us in the face of the impacts of climate change’, says Professor Seddon. Protecting our habitats, grasslands, forests, and wetlands can secure and regulate water supplies, and shield infrastructure, communities and agriculture from flood erosion, landslides and damage from increasingly extreme weather systems.

Professor Seddon at Oxford's NbS Conference, 2024

Professor Seddon at Oxford's NbS Conference, 2024There are plenty of examples of successful nature-based solutions. In Sierra Leone, cocoa agroforestry projects have been introduced in some areas. Here, crops are grown among the trees and trees among crops at a lower cost than conventional production, saving 500,000 tonnes of carbon a year, improving local livelihoods, and avoiding deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Recent work by Oxford’s researchers has highlighted the importance of nature-based solutions to tropical nations in particular, who cannot meet their targets under the Paris agreement without investing in measures such as halting deforestation and restoring degraded land. In Brazil these actions alone will help the country meet 80% of its net zero goal.

But the scale of the challenge is considerable, and nature-based solutions must happen alongside the decarbonisation of our energy systems and the introduction of ambitious climate policies to achieve their mitigation potential. According to Professor Seddon, it requires a fundamental shift in our thinking and values. ‘Our economic system is actively investing in its own demise’, she says, by prioritising profit over planetary health. Every year over $7 trillion continues to be spent on environmentally harmful investments, such as in fossil fuels and industrial agriculture; ‘our house is on fire and we’re still pouring fuel on the flames.’

The Vice-Chancellor's Colloquium | Oxford University Department for Continuing Education.

Kamanamaikalani Beamer. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Kamanamaikalani Beamer. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Throughout the event, participants were encouraged to engage with art, film, and ceremonies led by indigenous elders that aimed to showcase the importance of nature and our interconnectedness with it. The conference venue, at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, further underscored the need to draw on our evolutionary past to plan better for a flourishing future.

Discussing the importance of nature connection, speakers put forward that we are not separate from the environment, but an integral part of it. This understanding can then foster a deeper commitment to protecting our natural world.

Delegates were challenged to consider the benefits of nature-based solutions beyond climate change mitigation, and to reflect on ways to reconnect with nature on a deeper level.

A mural painted in real-time during the conference. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

A mural painted in real-time during the conference. Image credit: Matthew Mulholland, Oxford Media Group.

Ceremonies and Cultural Integration

Delegates experienced the unique confluence of science, art, music, short films, and ceremonies, inviting them to pause, reconnect with nature, and contemplate our shared humanity and common ancestry with all of life. Indigenous elder Mindahi Bastida guided elemental ceremonies that marked the opening and closing of the event.

Invaluable Indigenous Perspectives

‘There is no separation between nature and culture’ conference speaker Kamanamaikalani Beamer, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

Humans are not separate from the environment but an integral part of it. This fundamental understanding fosters a deeper commitment to protecting and preserving our natural world. Our connection with nature is not just a philosophical concept; it is a practical, essential pathway to effective nature-based solutions

By respecting indigenous sovereignty, protecting ecosystem integrity, and embedding human rights, nature-based solutions can play a key role in addressing the climate and biodiversity crises. As a global community, we need to take bold, informed, and collaborative actions to care for that which sustains us.

Professor Nathalie Seddon, Director of the Nature-based Solutions Initiative at the University of Oxford

Holistic Solutions and Community Empowerment

There is an urgent need for holistic approaches to environmental issues, with integration across disciplines to break down research and policy silos. This fosters collaboration and innovation, leading to more comprehensive and effective solutions.

Call to Action

Participants unanimously called for bold, collaborative actions to safeguard our planet's biodiversity and support social-ecological flourishing. The conference concluded with a shared commitment to scaling nature-based solutions ethically and effectively, ensuring they contribute to building an economy that is in service of the flourishing of life on Earth.

Recordings of the conference sessions will be available soon on the NbSI YouTube channel.

At this year's Skoll World Forum Oxford University Innovation (OUI) showcased five social ventures from the University of Oxford changing lives and impacting the environment.

The University’s support for social ventures through OUI started in 2018. Since then 18 social ventures have been created, positively impacting society and making a difference in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Discover five social ventures making waves below:

Greater Change: Alleviating homelessness through empowerment

Greater Change is revolutionising how we approach homelessness by providing financial planning support and micro grants to help those in need overcome financial barriers. With over 670 people supported and 80% now in stable housing, this unique approach has proven to be effective in helping those experiencing homelessness get back on their feet. The best part? Greater Change’s approach is scalable and can quickly plug into partners across wide geographies.

Wise Responder: Creating multidimensional wellbeing

Wise Responder is empowering social investments and sustainable human development goals by providing social metrics for financial institutions, investors, companies, and governments to tackle the world’s declared number one goal: United Nations SDG1 – No Poverty. By identifying deprivations at the individual and household levels, including health, education, and living standards, Wise Responder is making a significant impact on poverty reduction. The company is also helping to create sustainability-linked financing and investment options for financial institutions, corporates, and investors eager to make a difference.

Rogue Interrobang: Using creative thinking to solve wicked problems

Rogue Interrobang is helping individuals and organisations unlock their potential and create a better world. With offerings that include creative thinking training, diversity workshops, and coaching, Rogue Interrobang has worked with high-profile clients like the Cabinet Office, HMRC and the Open University. Their products include Mycelium, a card game that promotes creativity, and books “Our Dreams Make Different Shapes” and “Lift,” are just a few examples of how Rogue Interrobang is helping individuals tap into their full potential.

SEREN: Delivering life-saving diagnostic solutions in Africa

SEREN is working to improve access to diagnostic solutions in lower middle-income economies, like Tanzania, where cancer, anaemia and inherited diseases are a major health problem. SEREN provides DNA-based tests for as little as $10, making life-saving diagnostics accessible to those who need it most. Their cloud-based data systems allow for remote analysis and rapid diagnostics by experts so that samples don’t need to be sent abroad and valuable data can be used to further research and the provision of patient solutions.

Nature-Based Insetting: Creating Sustainable Supply Chains for a Healthier Environment

Nature-Based Insetting is helping organisations implement evidence-based targets for mitigating and insetting impacts on climate, biodiversity, and society through nature-based solutions. By enhancing the value and resilience of supply chains, Nature-Based Insetting is making a positive impact on our environment and promoting socially just, nature-positive, and net-zero pledges. With collaborations like Reckitt for biodiversity and net-zero targets, Nature-Based Insetting is helping individual businesses make a significant impact on sustaining a healthy, functioning natural environment and a stable climate system.

The full portfolio of social ventures can be viewed here.

Contact a member of OUI's social ventures team with your questions.

Some people are so energetic, dynamic and enthusiastic, they make you feel as though you do nothing but watch box sets while eating ice cream. But Nathalie Seddon’s passion for protecting nature and addressing climate change, makes you want drop the remote and follow her into the rainforest or the corridors of power, wherever she is going next. And you would not be alone.

Some people are so energetic, dynamic and enthusiastic, they make you feel as though you do nothing but watch box sets while eating ice cream. But Nathalie Seddon makes you want drop the remote and follow her

Oxford’s Professor of Biodiversity, from the university's Zoology department and Wadham college, is rightly something of a celebrity in the eco world. She is an official ‘friend’ of the COP26 climate conference. She has the ear of leading politicians and policymakers and she has been a determined force in the move to give ‘nature’ a place at the climate change top table.

Such concerns, plus expertise and leadership in climate and biodiversity has brought together key scientists and researchers, including Professor Seddon, from across Oxford's different departments and disciplines to deliver cutting-edge research, information and policy advice. The team includes Zoology, the Environmental Change Institute and the Smith School and initiatives such as Oxford Net Zero, the Oxford Martin School Programme for Biodiversity and Society and the Nature-based Solutions Initiative (Ever busy, Professor Seddon is a co-PI of the first two and directs the last).

But, in 2017, when Professor Seddon established the Nature Based Solutions Initiative at Oxford, few were talking about how nature fitted into discussions about global warming.

‘As a term, nature-based solutions wasn’t really in the lexicon,’ she says. ‘Now, it’s gone mainstream, viral even; now everyone seems to be talking about them – not just the conservation organisations, but those working in development, health, local businesses, banks, international corporations and governments.’

As a term, nature-based solutions wasn’t really in the lexicon. Now, it’s gone mainstream, viral even; now everyone seems to be talking about them

Professor Nathalie Seddon

Indeed, enter the words ‘nature-based solutions for climate change’ into Google, and a million results seem to pop up. It is one of the main themes for the UK-hosted climate change meeting in Glasgow in November (COP26) and at the forefront of discussions around climate change. And Professor Seddon, the doyenne of NbS [as they are known] is one of only 30 ‘friends’ of COP26, of whom just a handful are scientists.

But, until recently, Professor Seddon’s career involved far more hard science than scientific lobbying – although it also demonstrated the sort of single-minded determination which is proving so useful in pushing nature up the climate agenda. Her supportive parents encouraged her passion for nature but were not academics. Instead it was her headmaster who suggested that nature-mad Nathalie apply to study Natural Sciences at Cambridge. She won a place – and, to underline his conviction, did not leave until she had completed a doctorate and a junior research fellowship.

During the next 15 years, she travelled the world to study the lives of unusual birds and their songs. But this was not birdwatching as we know it [don’t mention the word twitcher].Then, as now, enthusiasm was her watchword. In her first year, the young student found a piece of paper on a noticeboard, asking for a birdwatcher for an expedition to Peru. It was a life-changing moment for a girl who had been mapping bird territories in her back garden since her family moved to the country when she was eight.

The Peruvian rainforest, by Chris Abney, Unsplash.

The Peruvian rainforest, by Chris Abney, Unsplash.Determined to go, she removed the paper from the board and a few months later found herself on a quest to find the Long-Whiskered Owlet while hiding from Shining Path guerrillas near the Peruvian border with Colombia. It was, perhaps, not the best way to start a life of scientific investigation. But her adventures did not stop there. That trip marked the beginning of a long passion for tropical wilderness and a fascination for understanding its unparalleled diversity.

To undertake her doctorate on the social behaviour and conservation of a threatened species of bird, the Subdesert Mesite (see below right), Nathalie had to drive solo across Madagascar in an ancient ex-military Land Rover she had transported by boat from Southampton. It might have been better had it never arrived since she spent more time trying to repair it than collecting data. And she says, ‘It turned out to be very challenging to study Mesites, as they live in the dense undergrowth of prehistoric spiny forests.’

Credit: Shutterstock. The Subdesert Mesite.

Credit: Shutterstock. The Subdesert Mesite.She says, with considerable feeling, ‘I loved being in those places....I am hugely privileged to have had worked there and those experiences enrich my every day and inform so much of the work I do. '

'Back then I was motivated by wanting to understand tropical diversity; now I am motivated by wanting to save it for future generations.’

Baobabs in Madagascar - by Haja Arson, Unsplash.

Baobabs in Madagascar - by Haja Arson, Unsplash.I discovered that hardly any knowledge we have about ecosystems and biodiversity was influencing big decisions that affect our futures...I found I could add value as a scientist to the policy environment...having children made me want to focus on the existential challenge that is climate change – and the intergenerational injustice we are perpetuating with our desecration of the natural world.

But what are NbS?

‘They are actions that involve working with nature for societal good,’ she says.

They involve community-led restoration and protection of mangroves, kelp forests, wetlands, grasslands and forests, bringing trees into working lands and nature into cities and much more.

It is now accepted that such actions can bring multiple benefits from storing carbon and protecting us from extreme events, to supporting biodiversity and providing jobs and livelihoods.

Critics sometimes argue that the potential contribution of nature to arresting climate change is tiny, compared with stopping fossil fuel use. But she insists, ‘Our work shows that nature has a role to play...and although new technology [to address climate change] might not be fully scalable until the end of the century, nature is here now, ready to be revitalised and can make a significant contribution to cooling this century.’

This is not mere dewy-eyed affection, although Professor Seddon clearly takes loss of biodiversity very personally.

‘Nature motivates, calms and grounds me,’ she says. But, she maintains, ‘We need nature because it is our life support system, because we are a part of it, not separate from it. There is huge value in the natural world, economically and ecologically, and huge risks of ignoring it...we have built our economies as if nature has no value; climate change and pandemics are showing us this not sustainable and that it is now time to repay our vast debt to nature.’

It is not just politicians, though, who have heard the call for nature – businesses too have made bold pledges. Everyone has heard about tree planting as an NbS. But this has not always been a positive move and some have planted trees to ‘offset’ their continued use of fossil fuels.

There is huge value in the natural world, economically and ecologically, and huge risks of ignoring it...we have built our economies as if nature has no value; climate change and pandemics are showing us this not sustainable and that it is now time to repay our vast debt to nature

Professor Seddon is concerned so-called ‘greenwashing is a really big issue’. She adds, ‘We need wood, and commercial planting can sometimes take the pressure off biodiverse native forests...also, in some parts of the world, where the land is badly degraded, tree plantations can help bring back soil health and are a step towards natural regeneration.’

But she warns, ‘Plantations are really bad news when they replace native habitats and violate human rights, and when they delay or distract from the urgent need to decarbonise.'

Professor Seddon is emphatic, 'Tree planting is not alternative to keeping fossil fuels in the ground...if we don’t, the resultant warming will undermine nature’s capacity to support us.'

She insists we cannot afford to ignore the harm we do to nature, ‘Covid shone a light on the risks of continued disrespect of the natural world. It also showed us that we cannot continue to travel and consume as much without paying severe consequences.’

But Professor Seddon has high hopes of the climate summit this year, where nature is a key theme.

‘For the UK,’ she says. ‘This is a real opportunity to show leadership. But to do that that, we need to get our own house in order and to shine light on good practice on nature-based solutions in our own country to inspire action globally.

‘We also need to end all the harmful subsidies that encourage land degradation and over-fishing and instead properly incentivise the careful stewardship of nature.’

We need to get our own house in order and shine light on good practice in our own country to inspire action globally...we also need to end all the harmful subsidies that encourage land degradation and over-fishing

Professor Seddon acknowledges the enormous role the great polluters need to play in reducing carbon emissions, but she sees considerable room for personal action, although it will mean substantial change for individuals, starting with moving, if possible, to a plant-based diet.

And, says the former globe-trotter, she could not quite bring herself to get on a plane again, unless there were a very good and urgent reason. And she says, ‘Scientists need to work with businesses and government to help them set realistic and robust evidence-based targets for climate and nature, and advise on how to reach those targets without compromising other goals for food security or economic recovery.’

Treading the corridors of power is a new path for Professor Seddon. But climate concerns have brought together scientists, looking for solutions, doing the hard-science to inform policy. She says, ‘There is a lot of really exciting fundamental research to be done to shore up the evidence around the value of working with nature in a warming world.’

She adds, ‘At Oxford, to address these knowledge gaps and meet policy needs, we’ve gone up a gear, we are working together more.’

And Professor Seddon is very much engaged in university life - delivering lectures, as Admissions Coordinator for Biology, interviewing candidates and working with young researchers and students. She says, 'Young people come asking what they should study to be part of it – to help. It’s our job to show them there is much they can learn and do, that they have real agency in their futures.'

At Oxford, to address these knowledge gaps and meet policy needs, we’ve gone up a gear, we are working together

She adds, ‘I am excited to be getting back into the science and to be working with colleagues from across the University and country to address fundamental questions about how we scale-up NbS...

'The next 10 to 20 years are going to be critical...Now is when the world needs us all to collaborate to enable transformational change.’

She concludes with hope for the future, ‘There is such a lot of good work going on around the world. Thousands of communities across the globe are implementing nature-based solutions to deal with climate change impacts, protect nature and support livelihoods. It is really inspiring. We all have a say in our futures...and as we work with nature we will heal ourselves.’

See latest research here. And a talk on NbS here: Evaluating and investing in Nature-based Solutions with Nathalie Seddon & Cameron Hepburn - YouTube

- 1 of 2

- next ›

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools