Features

As the planet warms, and our population grows, there is an ever-increasing pressure on natural resources. It has been estimated that ‘stressed’ crops - from changing weather patterns, drought, flooding and extreme temperature - may reduce production by as much as 70%, which will have devastating impact on our ability to feed the world.

‘It’s becoming increasingly clear that such post-translational regulation of chloroplast proteins is vital for plant growth and productivity, and thus of course for food production’. Professor Paul Jarvis

It has become increasingly urgent that we develop improved crop varieties - plants with enhanced nutritional value or resilience to adverse environments - and key to this development will be our understanding of the molecular basis of plant stress tolerance.

New research from the University of Oxford, published recently in the journal eLife, sheds fresh light on plant chloroplasts, and the proteins inside them. The regulation of chloroplast proteins is important for plant development and stress acclimation and is increasingly significant as plants - including our staple crops, wheat, rice, barley - are having to respond to our changing environments.

‘As the planet warms, it will be increasingly urgent to understand the molecular basis of plant stress tolerance.’ Dr Samuel Watson

All green plants grow by converting light energy into chemical energy via a process known as photosynthesis. Photosynthesis occurs within specialised compartments of plant cells known as chloroplasts. Chloroplasts require thousands of different proteins to function, and these are imported into the chloroplast via a specialised machinery known as the TOC complex. The TOC complex is, itself, made of proteins.

Recent studies revealed that the TOC complex is rapidly destroyed when plants encounter environmental stress - this protects plant cells from damage by limiting photosynthesis, which can generate toxic by-products under adverse conditions. This process has been named CHLORAD, for “chloroplast-associated protein degradation”.

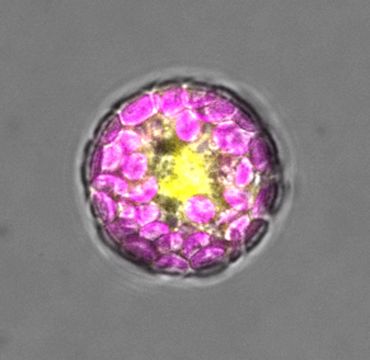

Plant cell (a protoplast) expressing the SUMO1 protein tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP); the chloroplasts inside the cell are coloured magenta in this image

Plant cell (a protoplast) expressing the SUMO1 protein tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP); the chloroplasts inside the cell are coloured magenta in this imageIn CHLORAD, the TOC complex is first marked with a small protein called ubiquitin. This ‘ubiquitination’ promotes the destruction of the complex, and thus suppresses chloroplast protein import, photosynthesis, and the production of toxic by-products.

‘This study has uncovered another layer of complexity within the systems that plants use to control their chloroplasts.’ Professor Paul Jarvis

In this study, researchers asked whether the TOC complex is also SUMOylated - SUMO is another small tag that is similar to ubiquitin - and, if so, what the function such TOC SUMOylation is.

The researchers found that the TOC complex is indeed SUMOylated, and that TOC SUMOylation also triggers the destruction of the TOC complex and is important for plant growth and development. These results are intriguing, as they indicate that SUMO action is very similar to that of CHLORAD, in this context.

In fact, the observed similarity with CHLORAD implies that SUMOylation regulates the activity of the CHLORAD pathway. This is particularly interesting, as SUMOylation is known to be induced by various forms of environmental stress and is a key driver of plant stress acclimation.

Professor Paul Jarvis, who supervised the work said: ‘It was remarkable when the role for ubiquitination, and CHLORAD, was discovered a few years ago, and this new role for SUMO just adds to the intrigue.’

Building on these discoveries, the researchers are currently exploring how the CHLORAD pathway can be manipulated to improve crop performance. Better understanding of the regulation of chloroplast protein import and/or the CHLORAD pathway, delivered as a result of the new findings reported here, will help to guide these efforts.

Professors of English Literature spend their lives asking the right questions, reading between the lines and interpreting texts. It is the day job. This skill means they are not the easiest people to interview; they know what you are going to ask before you ask it and they are questioning your motivation before you have finished speaking. However, Professor Abigail Williams is anything but the traditional academic and talks enthusiastically about her many lives and interests.

Professor Williams almost became an academic by accident. She never imagined becoming a Professor of English and, she says, she would have liked to go into advertising, except ‘she hadn’t really seen any adverts on television’, so did rather poorly in the interview. In an eclectic aside, she reveals she would also have liked to be a florist or a radio presenter. Apparently by chance, though, she is an Oxford scholar. Much of her work as an academic has been, quite literally, on the margins of English, studying unfashionable texts and even what readers wrote on books.

She says she is not a ‘Dead Poets’ Society’ sort, contemplating Great Literature (capital G, capital L), but then she talks about holding classes in museums and sounds quite a lot like the unconventionally inspirational teacher of English (capital E).

Professor Williams is not a ‘Dead Poets’ Society’ sort, contemplating Great Literature (capital G, capital L)

It is hard to keep up with the Humanities academic lead for Innovation. Professor Williams talks excitedly about her lockdown project - an interactive ‘game’ for teenagers, where they have WhatsApp-style ‘conversations’ with characters from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Typically focusing on the language, she does not use the term ‘game’ since young gamers see her ‘game’ as a very poor substitute for Grand Theft Auto. But, call it a ‘learning resource’, she says, and they love it. It is all about words.

Professor Williams loves to take English out of context and clearly enjoys breaking a few moulds on the way. From games, (sorry, learning resources), to working with a perfumer, on a range of historically-inspired fragrances, to musing on ‘Between the Sheets’, as an appropriate title for a forthcoming book on reading in bed, Professor Williams confounds conventional stereotypes and seeks to reach wider audiences with her love of literature.

Born in London, but raised on a commune in Dorset, she did not have the most conventional start. It was not the sort of troubling 1970s communal experience, which features from time to time in the popular press, but a collection of professional people who gave up the professions they were good at, to do things they were not really good at, she laughs.

In an early example of her atypical journey, she went from her commune to a scholarship place at a prestigious local convent school.

‘I really liked English,’ she says. ‘We had some very impressive English teachers, I suppose, in a Dead Poets’ Society way...but that is not the sort of English I have ever done.’

She won a place from the convent to come to Oxford to study English, potentially the last conventional thing she has done.

‘It was amazing, eye opening,’ says Professor Williams. ‘When you arrive, you do a lot of comparing with other people and, suddenly, you may have been the best at school, but now you realise you’re just one fish in a big sea....It took a while before I found what I was good at.’

Leaving the university on graduation, she enjoyed exploring opportunities but was, as she cheerfully admits, woefully unprepared for her chosen career of advertising.

‘My interview was a disaster,’ she says with amusement. ‘How could I talk about something, when I knew nothing about it?’

So she returned to Oxford for postgraduate study and took an MPhil in 18th century literature, ‘It was a brilliant course, a really good grounding.’

It was then that Professor Williams’s journey took another sideways move - she began studying less well known 18th century poetry, not Pope or Swift or the other acclaimed Tory poets, but their forgotten Whig counterparts. Very popular in their day, but now virtually unknown, these poets were given to paeans of praise about William III and his bloody wars. To modern ears, they are ‘dreadful’, according to Professor Williams. But she is intrigued by the fact that they were so popular and praised when written.

‘They were thought terrific in their day but seem so recherché and unpalatable now,’ she says. ‘People say great art transcends time, but Whig poets wrote about things which no one would want to read about now. It is awful jingoistic dross and yet at the time was loved by the most successful people in the country.

‘I want to understand the head set of that; the psychology of that aesthetic change.’

People say great art transcends time, but Whig poets wrote about things which no one would want to read about now. It is awful jingoistic dross and yet at the time was loved...I want to understand the head set of that; the psychology of that aesthetic change

Professor Williams

Another less popular area of research, which is a great interest of Professor Williams, is ‘marginalia’: what people wrote on their books, the underlinings, the notes, the words in the margins. She is interested in what people were saying about their books and, like the Whig poetry, how historical readers might be different from modern ones. In future, she predicts, scholars will look at social media to interpret the reception of literature, as well as the marginalia.

With growing debate about content warnings and offensive material in historical works,’ Professor Williams says it is important to recognise that novels in particular have always been controversial and ‘dangerous’.

‘Northanger Abbey was all about the dangers of novel reading,’ she says. ‘It has always been a matter of concern; the isolated reader, getting inside the consciousness of the writer. We worried in the 18th century about some kinds of novels and their content and we worry now about different ones. Students might register discomfort at some texts, but this is the reality of literature and what we are here to explore.'

And, she says enthusiastically, ‘English has become more global, we talk about Englishes and the range of writers has expanded, there is more diversity. We’re less hung up now on doing things the way they were when we were students.’

Northanger Abbey was all about the dangers of novel reading...It has always been a matter of concern; the isolated reader, getting inside the consciousness of the writer. We worried in the 18th century about some kinds of novels and their content and we worry now about different ones. Students might register discomfort at some texts, but this is the reality of literature and what we are here to explore

She adds, ‘It’s great to help students understand the world the works were written in, so how better to understand Georgian novels than to spend an afternoon looking at tea pots and snuff boxes at the museum...it’s a better way of teaching.’

Professor Williams is determined to see the enjoyment brought by literature spread, which is why she threw herself into developing Will Play, her Shakespearean learning resource, during the pandemic.

‘It was trialled at my children’s school...I wore a hoodie to disguise myself, because they were so embarrassed...it was great fun to see them use it. It became a gateway into reading.

‘English Literature teaching has always used different routes...you can empathise with the characters, engage with the texts...it was really exciting seeing how Shakespeare was embraced.

‘They really got into it, messaging the characters and even warning them about what was going to happen.’

There has developed a link between cleverness and obscurity, with almost a contempt for language that is understood. I would like to uncouple those things....You should be able to say something clearly

Professor Williams is almost evangelical in her wish to reach out to audiences, admitting that she would also have liked to be a radio presenter, underlining her emphasis on the importance of communication. She maintains, ‘There has developed a link between cleverness and obscurity, with almost a contempt for language that is understood. I would like to uncouple those things.’

Before disappearing into the Oxford street, the Professor of English Literature says thoughtfully, ‘You should be able to say something clearly.’

Prof. Jonathan Doye

Prof. Jonathan DoyeMost people who have done some chemistry will have seen examples of how the directionality of the covalent bonding for a given element can determine the crystal structures they form. For example, the tetrahedral bonding of carbon atoms naturally leads to the crystalline structure of diamond. But to better understand this challenge, we first need to explain what a quasicrystal is.

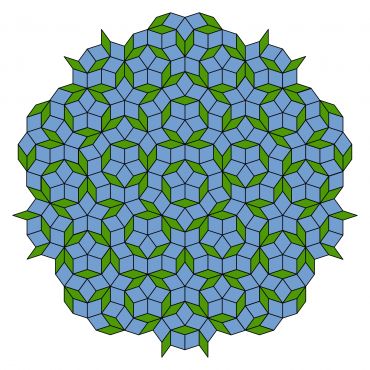

We should start with a discovery of Sir Roger Penrose, an Oxford mathematician and physicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2020. In 1974 he showed that one could tile a plane with just two types of tiles, such that the tiling has no repeating pattern but has a kind of 5-fold symmetry that is not possible for crystals. These Penrose tilings, one of which is shown below, are said to have “quasiperiodic order”.

An example of a Penrose tiling

An example of a Penrose tiling

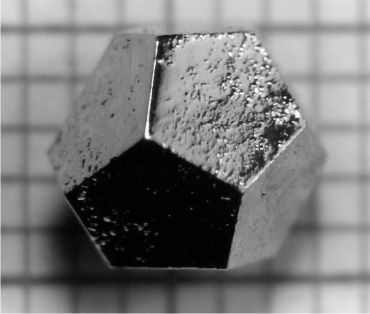

The order of these quasicrystals is revealed by the diffraction patterns that result when electrons or x-rays pass through them. They are labelled as icosahedral, because like the icosahedron that is one of the Platonic solids, there are six axes along which five-fold symmetry is revealed in the diffraction patterns. Like crystals, this underlying symmetry can also be revealed by the shapes into which quasicrystals grow, such as the dodecahedron below. Dan Shechtman’s paradigm-shifting discovery led to him receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011.

A large quasicrystal with a docahedral shape that is a consequence of its underlying non-crystallographic icosahedral symmetry

A large quasicrystal with a docahedral shape that is a consequence of its underlying non-crystallographic icosahedral symmetryThis discovery led to an intense search for other examples of icosahedral quasicrystals. Many were found, including even natural examples in meteorites, but all were metallic alloys, whereas none have been found in covalent materials where the bonding is directional.

This raises the question of whether, if one is not restricted by the geometry of covalent bonding that is allowed by atoms, it might be possible to design particles that could form icosahedral quasicrystals through directional bonding. In 2014 Eva González Noya, my collaborator at CSIC in Madrid, and myself set ourselves the task of finding computational models that could achieve this.

One of the challenges we faced is that the structure of quasicrystals is more complex to describe than periodic crystals. For example, if one has the diffraction pattern for a crystal, one can work out exactly where all the atoms are in the unit cell. However, for an icosahedral quasicrystal, one instead gets a description of the quasicrystal in terms of a crystal in six dimensions!

Some help came from computational experiments by the group of Sharon Glotzer at the University of Michigan in which icosahedral quasicrystals formed in systems without directional bonding. Although these provided examples where the positions of all the particles were known, they revealed another challenge: although the icosahedral quasicrystals have beautiful long-range order, locally they are quite disordered. For example, if one was to try to have particles that reproduce all the different patterns of local bonding in this example, the number of types of particles needed would be far too large to be practical.

Progress was gradually made, a key insight being that one should not be too fussy about whether a particle is able to form all its possible directional bonds, and in 2018 a first example system consisting of five particle types was found that assembled into an icosahedral quasicrystal in simulations; later, this was simplified to a system of two particle types.

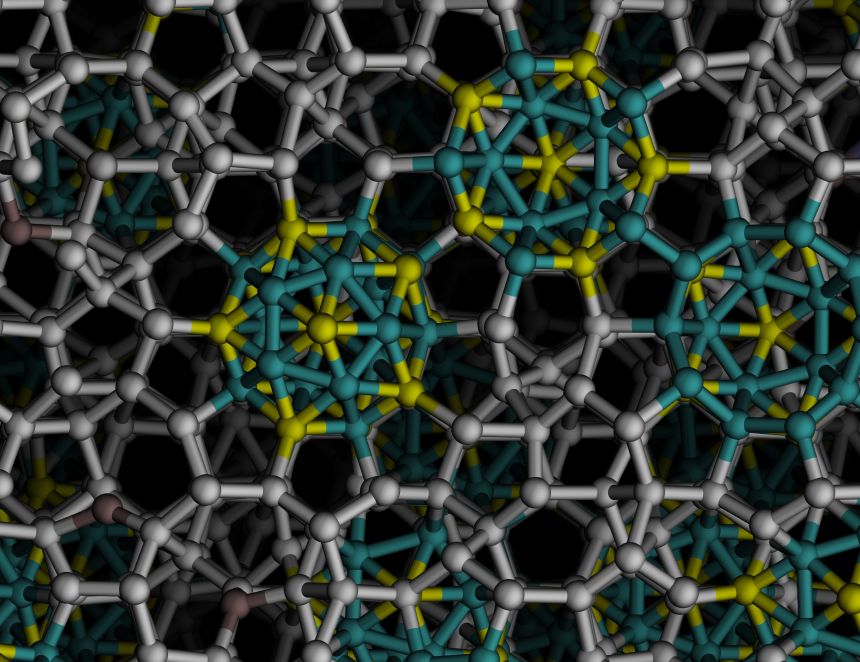

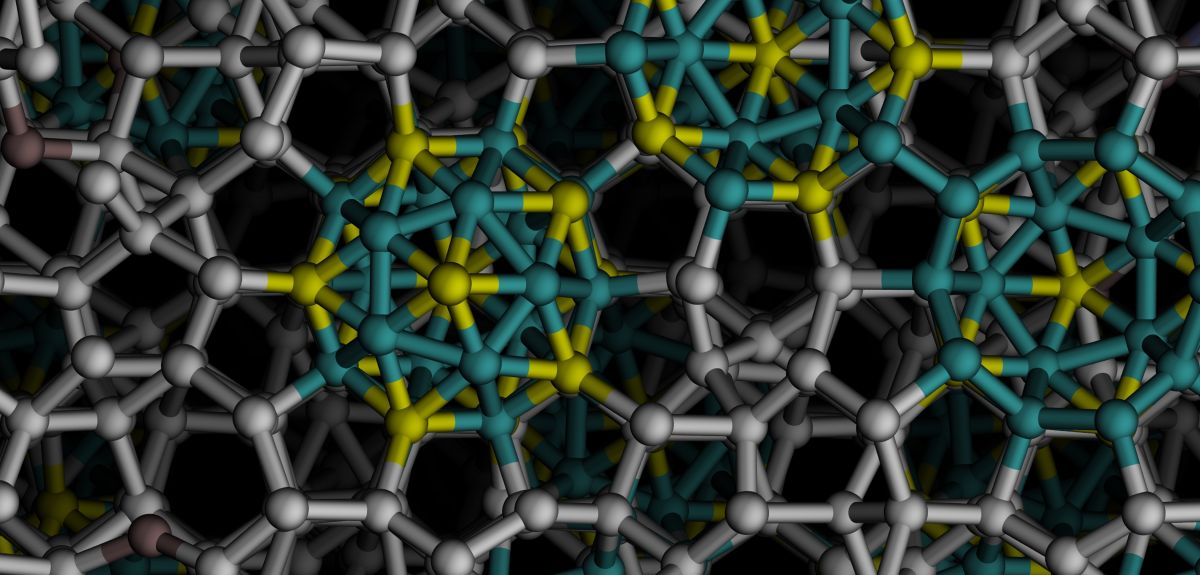

And to show the generality of the design principles, a second quasicrystal-forming system was developed that had a totally different pattern of local directional bonding. Somewhat like the metallic alloy examples, key building blocks are icosahedral clusters (the yellow and cyan rhombic triacontahedra in the image below) which form in a matrix of particles that propagates the global order.

A close-up of a cut through one of the icoshedral quasicrystals grown in our computational experiments viewed along a five-fold axis of symmetry.

A close-up of a cut through one of the icoshedral quasicrystals grown in our computational experiments viewed along a five-fold axis of symmetry.Of course, an important question is whether these computationally discovered quasicrystals could be realized experimentally. Although it is unlikely that they could be formed by atomic materials, atoms are not the only particles that form crystals. Nanoparticles and colloidal particles can also form crystals; for example, precious opals are crystals of colloidal silica spheres and their iridescence results from the diffraction of light by these crystals.

Recently, crystals made up from building blocks made of DNA have been realized. The beauty of these DNA nanotechnology techniques is that the shape of the DNA particles and the interactions between them can be almost arbitrarily controlled. Computational modelling of such DNA particles suggests that making icosahedral quasicrystals from DNA origami particles could well be feasible.

How to design an icosahedral quasicrystal through directional bonding, Published 18th August 2021, Nature.

By Ruth Moore, TORCH Theatre and Performance Officer.

When theatres shut on 16 March 2020, no one imagined that ‘going dark’ would last so long and cost so much.

As the weeks dragged on, theatre historians reminded us of closures for plague and war in the 16th century and the Blitz, and speculated about how quickly live performance would bounce back. For theatre decision-makers in Oxford and around the world, the 21st century calculations were terrifying. In the UK, the government's Cultural Recovery Fund grants made the difference for some, but others were not so fortunate. And the plight of freelance artists, the lifeblood of the theatre industry, is well documented.

Here at TORCH, The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, we watched from the wings, supporting our projects to adapt, and seeking ways to amplify conversations about the future of live performance. We find ourselves in another uncertain phase. Theatres are legally able to operate at full capacity, but there are continuing concerns over self-isolating cast members and anxious audiences. Here we look back at some of the emergent themes of theatre in a pandemic.

Duchess of Malfi, Creation Theatre 2021 (Actors Kofi Dennis and Andy Owens)

Duchess of Malfi, Creation Theatre 2021 (Actors Kofi Dennis and Andy Owens)

From the beginning, it was evident that, while theatre buildings went dark, theatre itself would not be silenced by the virus. An amazingly diverse range of virtual theatre sprang up. It was ‘unified as a genre only by its reliance on Wi-Fi’, as Vinson Cunningham wrote in the New Yorker.

Theatre lovers could spend virtually every minute of lockdown watching premieres of glittering ‘NT At Home’ productions such as Small Island and Angels in America, or browsing through the back catalogues of a global collection of theatre companies, or debating whether to brave going ‘camera on’ for live, experimental Zoom performances.

To those who know the theatre world well, this outpouring of creativity came as no surprise. Speaking at a TORCH event, Ria Parry, co-director of the North Wall Arts Centre reflected, ‘You give a problem to artists and it's not a problem… it's a challenge… put a load of graft and talent in the mix and suddenly it turns into something extraordinary and beautiful and brilliant.’[1]

Sometimes, the experience really was extraordinary. Oxford’s innovative Creation Theatre Company was in the first wave to push the limits of live-streamed performance, including a partnership with Big Telly and Charisma.ai to see audiences caught up in the action in ‘Alice: A Virtual Themepark’. That same can-do, innovative spirit infused a recent Knowledge Exchange production of The Duchess of Malfi, with Dr Laura Wright.

Adventures in Digital – image Creation Theatre. Design Keiko Ikeuchi

Adventures in Digital – image Creation Theatre. Design Keiko IkeuchiSpeaking about the ground-breaking digital repertory company used for Malfi, Artistic Director Lucy Askew said, ‘We can really start to build on each experience and each show and unpick different things and explore different kinds of digital propositions with each piece of work.’[2]

As companies large and small worked with these new formats, it became evident that the pandemic was accelerating an existing trend. Sarah Ellis, Director of Digital Development at the Royal Shakespeare Company, noted, ‘What happened was this form of accelerated disruption… we'd been slowly emerging into those hybrid worlds and then suddenly with the pandemic it cracked open the future in the moment that we were in and exposed the fact that we're very much first draft in this space.’[3]

First draft, perhaps, but the drafts are exciting, and speaking at the same event, Oxford Professor Emma Smith, who has worked with the RSC, expressed her hope that, as we emerge from the pandemic, ‘That there isn't a reactionary move towards an idea of theatre which is in some ways quite limited.’[4]

Of course, many have felt the loss of being ‘in the room’. But, at TORCH and among our partners, we have also felt a deep appreciation for the way virtual events have opened us up to new audiences. Barriers of all kinds - geographical, financial, socio-cultural - have been broken down, and the mood is clear: theatre must build on this.

Building a stronger theatre

Oxford Playhouse for the #lightitinred campaign; by Ash Bale, Oxford Playhouse

Oxford Playhouse for the #lightitinred campaign; by Ash Bale, Oxford PlayhouseMany theatres are considering how to retain and develop the online audiences they have won, even as doors re-open. This includes the Young Vic’s ‘Best Seat in Your House’ project, an audacious decision to provide a livestream of every play going forwards.

For the first time, audience members who do not want to be in the room or who physically cannot be in the room are being heard. With the emergence of hybrid methodologies, theatres can offer them a choice – although the additional costs can be difficult to navigate.

The same hybrid thinking is evident among theatre outreach and learning teams. These behind-the-scenes professionals provided a vital lifeline between theatres and audiences throughout 2020, and again showed extraordinary resilience in working out how to adapt. While some participants are anxious to get back in the building, others found new possibilities online. Paul Simpson, Participation Manager at Oxford Playhouse noted an ability ‘to be in some instances more expressive because they're in the comfort of their own homes'. [6]

Another pressing theme in the past year has been the need to pay close, practical attention to dismantling racism within the cultural sector. Even as members battled to keep their organisations afloat, Oxford’s Cultural Partnership worked collaboratively to form the Oxford Cultural Anti-Racism Alliance. A successful Arts Council bid is now fostering cross-institutional efforts to support Global Majority artists, to embed better recruitment practices, and to champion leadership development. Across the industry, similar initiatives are gaining ground.

There is a lot to be excited about, and many have noted a remarkable spirit of collaboration across the industry through each stage of the pandemic. As theatres move forward in exploring all these areas, we hope that this spirit will endure. At a recent event, James Dacre, Artistic Director of Royal & Derngate Theatres, Northampton, emphasised, ‘The importance now of making work, touring work, and reigniting the sector… ensuring that the support that we've been lucky enough to have from our audiences, from government, from local authorities now can go directly towards engaging the freelance workforce who are the lifeblood of course of our sector in every way.’[7]

But with finances still precarious for everyone from commercial theatre producers to small touring companies, there are many delicate questions about what is programmed and whom is cast. To make bold decisions in these areas requires an answering boldness in audiences.

As the curtain goes up

Farewell to Zoom? design Keiko Ikeuchi

Farewell to Zoom? design Keiko Ikeuchi19 July 2021, the much touted ‘freedom day’, turned into a day of misery for some theatres with a string of high-profile show cancellations and delays because of the ‘pingdemic’. As we wait to see how theatres fare through the late summer of 2021, we urge ourselves and our networks to support every way we can.

Arifa Akbar, the chief theatre critic at The Guardian, spoke for many when she said theatre in the pandemic, ‘Became much more self-reflective… I found myself engaging with those things and… the ideal of what theatre could be; what we, what I might hope for it to be when things open up again.’[8]

As curtains go up around the country, hope can be shown in the tickets we buy, the reviews we share, and the projects we commission.

With thanks to all who took part in our recent conversations, and to support from the Higher Education Innovation Fund and the University’s KE Seed Fund.

[1] Ria Parry, ‘Never Such Innocence’, 29 March 2021

[2] Lucy Askew, ‘Adventures in Digital’, 4 March 2021

[3] Sarah Ellis, ‘A Farewell to Zoom?’ 10 June 2021

[4] Emma Smith, ‘A Farewell to Zoom?’ 10 June 2021

[5] Louise Chantal, ‘Never Such Innocence’ 29 April 2021

[6] Check out discussion in ‘It’ll Never Work on Zoom’, 20 May 2021

[7] James Dacre, ‘Never Such Innocence’ 29 April 2021

[8] Arifa Akbar, ‘Never Such Innocence’ 29 April 2021

What people do not say can be as interesting as what they do, says Dr Ridhi Kashyap. Along with Connor Gilroy of the University of Washington, the Oxford demographer has been studying the disclosure of information on Facebook linked to sexuality in the United States.

Their study, published last month, reveals some possibly predictable findings such as: older social media users are less likely to disclose the gender in which they are interested, than younger users. But more unexpected findings have also come out of the data, say the authors, such as that women in their 20s and early 30s are twice as likely as older women to identify as bisexual, and women are more likely to identify as bisexual or homosexual than men.

A very interesting aspect of the aggregated and anonymised data is that it reveals what Facebook users were prepared to say about themselves in terms of their sexual identity. They chose to make this information public – or not

According to Dr Kashyap, a very interesting aspect of the aggregated and anonymised data is that it reveals what Facebook users were prepared to say about themselves in terms of their sexual identity. They chose to make this information public – or not. It makes a fascinating study, she says - as these differences in who discloses, or not, displays interesting variations by age, gender and relationship status and reveals for whom sexual identity is likely to be salient.

Such data offers a novel opportunity for demographers and sociologists, as they provide a window into the lives of respondents about what people will offer up about themselves when they are not being officially surveyed.

You can see how people signal themselves...[our study] encompassed 200 million Facebook users, 28% (56.3 million) of whom revealed sexuality-related information

Dr Ridhi Kashyap

‘You can see how people signal themselves,’ says Dr Kashyap. ‘They were not doing this in the context of a survey or a data collection exercise such as a census, but for themselves and their social networks and communities.

‘The data generated when we use social media platforms provide a different but complementary perspective to one offered by more classic social science approaches, which rely on asking and getting a response.’

She continues, ‘This, of course, also raises important and new types of ethical issues for researchers to consider, and requires us to be careful and considerate in how we use the data. In our study, we used only aggregated counts – so no individuals can be identified. It encompassed 200 million Facebook users, 28% (56.3 million) of whom revealed sexuality-related information and describe patterns that we observe.’

Mr Gilroy says interesting patterns were revealed, ‘There are large generational differences, as younger social media users share their sexualities much more than older users. Younger users, and especially younger women, are also more likely to be interested in the same gender, or both men and women. For older users, marital status often substitutes for their sexual identity, whereas single people are more likely to disclose their sexuality.’

Younger users, and especially younger women, are also more likely to be interested in the same gender, or both men and women. For older users, marital status often substitutes for sexual identity, whereas single people are more likely to disclose their sexuality

Connor Gilroy

But, just as there are generational differences in disclosure and non-disclosure, there are gender differences.

‘Women are more likely to say they are bisexual than men,’ says Mr Gilroy. ‘Men are more likely to say explicitly that they are heterosexual – and not in a relationship.’

He wonders if the relative absence of heterosexual women, compared to heterosexual men, suggests women do not disclose for fear of being harassed online and appearing ‘available’.

But, he says, it was notable that there still appears to be some stigma around male homosexuality, given that more women than men disclosed same-sex and, more notably, bisexual interests. In the past, he says, the expectation was that people would be heterosexual and, even today, this comes with privilege for men, ‘Anxiety over male homosexuality is much greater [than female homosexuality]...but in the online world, women are concerned about attracting unwanted attention and worried about online safety [which can constrain disclosure].’

Younger generations are more likely to see their sexuality as an important aspect of their identity, which could explain why more are prepared to disclose

Non-disclosure is a fascinating area, say Mr Gilroy and Dr Kashyap but, they add, their study suggests sexuality has become for younger generations a ‘core demographic trait’ alongside ethnicity, gender and race.

‘Younger generations are more likely,’ says Dr Kashyap, to see their sexuality as ‘an important aspect of their identity’, which could explain why more are prepared to disclose.

- ‹ previous

- 14 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences