Features

The Moon’s polar regions are home to craters and other depressions that never receive sunlight. Permanently shadowed lunar craters contain water ice but are difficult to image. An AI algorithm now provides sharper images, allowing us to see into them with high resolution for the first time.

Near the lunar north and south poles, the incident sunlight enters the craters and depressions at a very shallow angle and never reaches some of their floors.

Dr. Valentin Bickel, MPS

Today, a group of researchers led by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, supported by the University of Oxford and the NASA Ames Research Center, have taken a closer look at some of these regions and presented the highest-resolution images to date covering 17 such craters in the journal Nature Communications.

Craters of this type could contain frozen water, making them attractive targets for future lunar missions, and the researchers focused further on relatively small and accessible craters surrounded by gentle slopes. Three of the craters have turned out to lie within the just-announced mission area of NASA's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER), which is scheduled to touch down on the Moon in 2023.

Imaging the interior of permanently shadowed craters is difficult, and efforts so far have relied on long exposure times resulting in smearing and lower resolution. By taking advantage of reflected sunlight from nearby hills and a novel image processing method, the researchers have now produced images at 1-2 meters per pixel, which is at or very close to the best capability of the cameras.

The Moon is a cold, dry desert. Unlike the Earth, it is not surrounded by a protective atmosphere and water which existed during the Moon’s formation has long since evaporated under the influence of solar radiation and escaped into space. Nevertheless, craters and depressions in the polar regions give some reason to hope for limited water resources.

'Near the lunar north and south poles, the incident sunlight enters the craters and depressions at a very shallow angle and never reaches some of their floors', MPS-scientist Dr. Valentin Bickel, first author of the new paper, explains. In this "eternal night," temperatures in some places are so cold that frozen water is expected to have lasted for millions of years. Impacts from comets or asteroids could have delivered it, or it could have been outgassed by volcanic eruptions, or formed by the interaction of the surface with the solar wind.

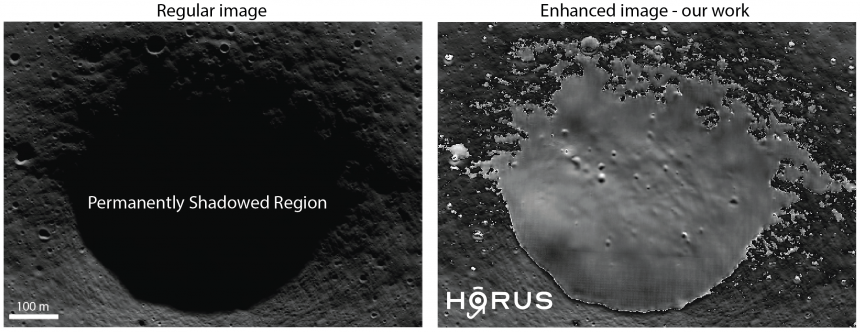

An as-yet unnamed crater (region 1 in figure below) near the Moon’s south pole and close to the proposed landing site of NASA's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover. Left shows an image taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Right shows the same image after our image processing. credits: left: NASA/LROC/GSFC/ASU; right: MPS/University of Oxford/NASA Ames Research Center/FDL/SETI Institute

An as-yet unnamed crater (region 1 in figure below) near the Moon’s south pole and close to the proposed landing site of NASA's Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover. Left shows an image taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Right shows the same image after our image processing. credits: left: NASA/LROC/GSFC/ASU; right: MPS/University of Oxford/NASA Ames Research Center/FDL/SETI InstituteMeasurements of neutron flux and infrared radiation obtained by space probes in recent years indicate the presence of water in these regions. Eventually, NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) provided direct proof: twelve years ago, the probe fired a projectile into the shadowed south pole crater Cabeus. As later analysis showed, the dust cloud emitted into space contained a considerable amount of water.

'With the help of the new HORUS images, it is now possible to understand the geology of lunar shadowed regions much better than before, Ben Moseley', Oxford University.

However, permanently shadowed regions are not only of scientific interest. If humans are to ever spend extended periods of time on the Moon, naturally occurring water will be a valuable resource - and shadowed craters and depressions will be an important destination.

NASA's uncrewed VIPER rover, for example, will explore the South Pole region in 2023 and enter such craters. To get a precise picture of their topography and geology in advance - for mission planning purposes, for example - images from space probes are indispensable. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has been providing such images since 2009.

However, capturing images within the deep darkness of permanently shadowed regions is exceptionally difficult; after all, the only sources of light are scattered light, such as that reflecting off the Earth and the surrounding topography, and faint starlight. 'Because the spacecraft is in motion, the LRO images are completely blurred at long exposure times,' explains Ben Moseley of the University of Oxford, a co-author of the study.

At short exposure times, the spatial resolution is much better. However, due to the small amounts of light available, these images are dominated by noise, making it hard to distinguish real geological features. To address this problem, the researchers have developed a machine learning algorithm called HORUS (Hyper-effective nOise Removal U-net Software) that "cleans up" such noisy images.

It uses more than 70,000 LRO calibration images taken on the dark side of the Moon as well as information about camera temperature and the spacecraft's trajectory to distinguish which structures in the image are artifacts and which are real. This way, the researchers can achieve a resolution of about 1-2 meters per pixel, which is five to ten times higher than the resolution of all previously available images.

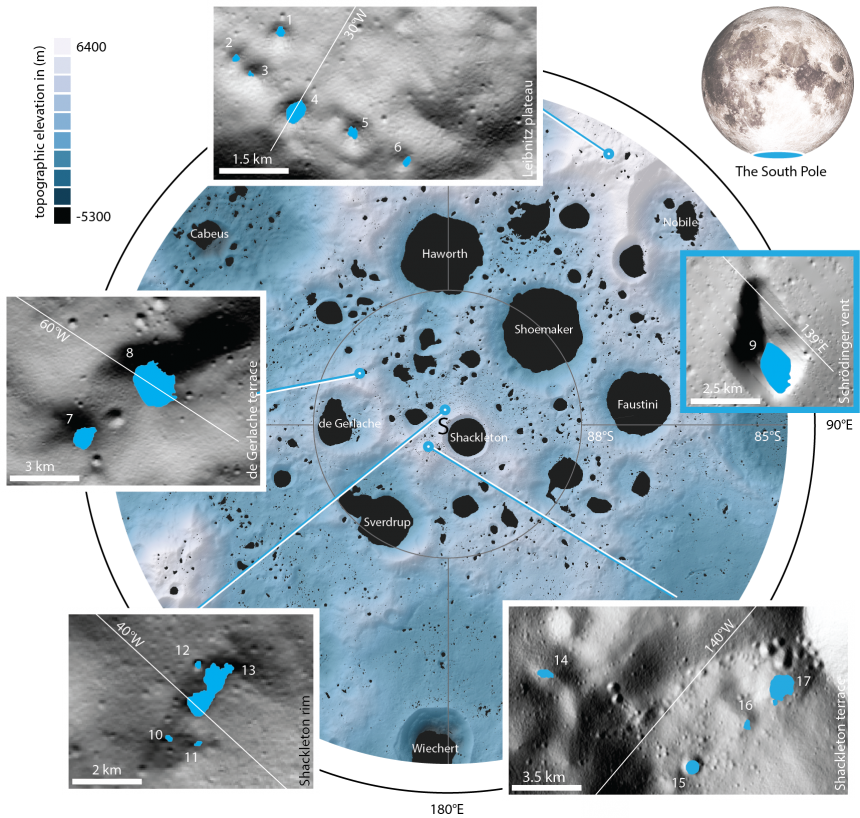

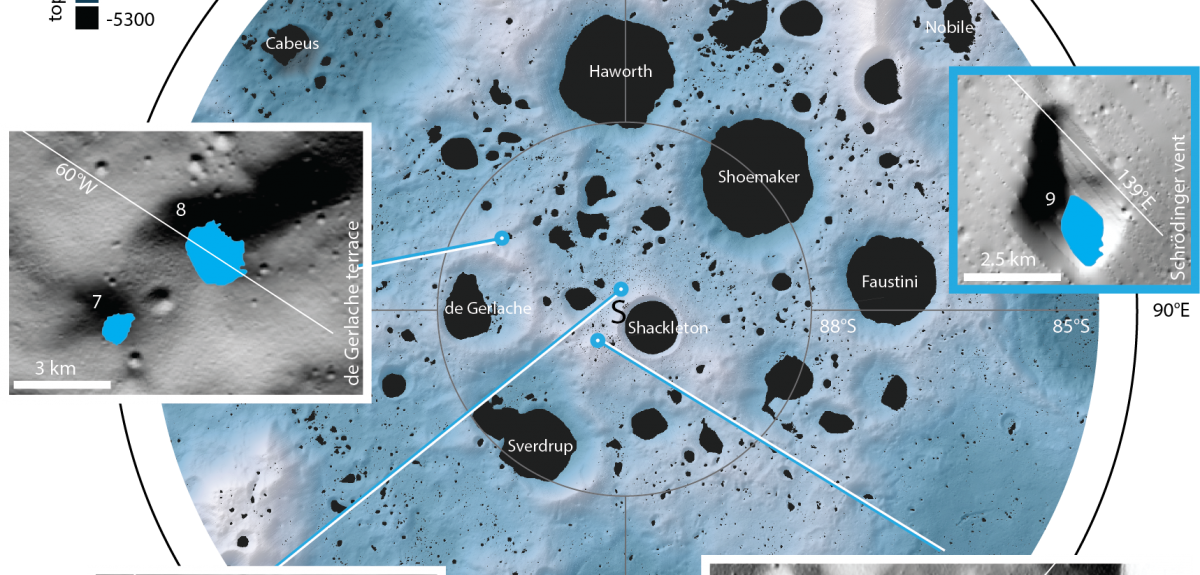

Using this method, the researchers have now re-evaluated images of 17 shadowed regions from the lunar south pole region which measure between 0.18 and 54 square kilometers in size.

In the resulting images, small geological structures only a few meters across can be discerned much more clearly than before. These structures include boulders or very small craters, which can be found everywhere on the lunar surface. Since the Moon has no atmosphere, very small meteorites repeatedly fall onto its surface and create such mini craters.

Because the spacecraft is in motion, the LRO images are completely blurred at long exposure times, Ben Moseley, Oxford University.

'With the help of the new HORUS images, it is now possible to understand the geology of lunar shadowed regions much better than before,' explains Moseley. For example, the number and shape of the small craters provide information about the age and composition of the surface. It also makes it easier to identify potential obstacles and hazards for rovers or astronauts. In one of the studied craters, located on the Leibnitz Plateau, the researchers discovered a strikingly bright mini-crater.

‘Its comparatively bright color may indicate that this crater is relatively young,’ says Bickel. Because such a fresh scar provides fairly unhindered insight into deeper layers, this site could be an interesting target for future missions, the researchers suggest.

The new images do not provide evidence of frozen water on the surface, such as bright patches. “Some of the regions we've targeted might be slightly too warm," Bickel speculates. It is likely that lunar water does not exist as a clearly visible deposit on the surface at all - instead, it could be intermixed with the regolith and dust, or may be hidden underground.

To address this and other questions, the researchers' next step is to use HORUS to study as many shadowed regions as possible. ‘In the current publication, we wanted to show what our algorithm can do. Now we want to apply it as comprehensively as possible,’ says Bickel.

This work has been enabled by the Frontier Development Lab (FDL.ai). FDL is a co-operative agreement between NASA, the SETI Institute (seti.org) and Trillium Technologies Inc, in partnership with the Luxembourg Space Agency and Google Cloud.

The 17 newly studied craters and depressions are located near the South Pole. Their sizes range from 0.18 to 54 square kilometres. Region 9 is not located in the section of the south polar region shown here, but a bit further to the North, in the Schrödinger Basin. credits: MPS/University of Oxford/NASA Ames Research Center/FDL/SETI Institute

The 17 newly studied craters and depressions are located near the South Pole. Their sizes range from 0.18 to 54 square kilometres. Region 9 is not located in the section of the south polar region shown here, but a bit further to the North, in the Schrödinger Basin. credits: MPS/University of Oxford/NASA Ames Research Center/FDL/SETI InstituteIn 2017 a provocative opinion piece was published by our WildCRU in the journal Animals; ‘A Cultural Conscience for Conservation’. The piece considered the idea of wealthy corporations paying royalties when they use symbolic animals in their logos, branding, or advertising to fund wildlife conservation of those species.

Despite the lion′s evident cultural appeal, its global population has fallen by approximately 43% over the past 21 years (and by 65% in West and Central Africa).

If these organisations were to give due recognition to the animal that they use - particularly for endangered animals - and donate a small percentage of their revenue to conservation initiatives, we could make great strides towards securing the future for endangered animals worldwide.

Around the same time this piece was published a popular professional baseball team in Japan, the Saitama Seibu Lions, acting on their ‘cultural conscience’, came up with the ideas of ‘Seibu Lions: Save the Disappearing Wild Lions Project’ that recognise the important role of their mascot and namesake, the Lion, on their teams and fans motivation and success.

With the kind assistance from The University of Oxford’s Japan Office the team connected with WildCRU’s Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme and formed an exciting partnership in early 2019 in which they committed to support lion conservation.

Saitama Seibu Lions, Japan, raise money for WildCRU's Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme. ⓒSEIBU Lions/TEZUKA PRODUCTION

Saitama Seibu Lions, Japan, raise money for WildCRU's Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme. ⓒSEIBU Lions/TEZUKA PRODUCTIONThe Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme is one of WildCRU’s larger research projects based in Zimbabwe and Botswana and combines field research on lion ecology and movement behaviour to inform conservation planning and policy, along with community projects to mitigate human-lion conflict and promote co-existence.

How might the lion′s symbol, so familiar as a marketing instrument, metamorphose once again, this time into much needed conservation revenue.

Amongst various fundraising activities once a year the team host a Save Lions Day at the team’s home – the MetLife Dome in Tokorozawa, Saitama Prefecture. Despite the COVID-19 challenges faced last year the event went ahead, and again, still committed to our partnership, the Saitama Seibu Lions will be hosting another day tomorrow, on the 23rd September.

This initiative taken by the Saitama Seibu Lions is inspirational and there is an opportunity here for others to follow suit and be part of a great shift that is desperately needed in wildlife conservation funding.

In the original WildCRU opinion piece, the authors highlighted the use of lions being used symbolically before considering some potentially very lucrative examples.

‘The lion is the most frequently invoked national animal, adopted by 15 countries worldwide from Singapore to Sri Lanka, Libya to Luxemburg. Today, the lion is extant in only two of these nations, Ethiopia and Kenya. But that has not deterred its symbolic, cultural proliferation.

‘Conservation is in crisis, and large sums are needed to fund it. Finding that money necessitates innovative financial mechanisms, and payments triggered by a cultural conscience could be a potent one.’ Professor David Macdonald, WildCRU’s Founder & Director

The British lion, introduced in the 13th century by King Richard “the Lionheart”, arrived millennia after lions themselves strolled through Pleistocene England. Richard I′s Plantagenet lions remain to this day.

Over the centuries, they have been placed on shields to scare the enemy, featured on flags and in crests for identification at sea and abroad, and posted in marble and stone as guardians of public buildings and national treasures. In more recent years, the British lion symbol has migrated onto food as a stamp of quality and as emblems of the country′s national sports teams, from rugby and football to Olympic team GB

But despite the lion′s evident cultural appeal, its global population has fallen by approximately 43% over the past 21 years (and by 65% in West and Central Africa). How might the lion′s symbol, so familiar as a marketing instrument, metamorphose once again, this time into much needed conservation revenue?

Take eggs. According to the British Egg Industry Council, 34 million eggs are consumed in Britain each day. The British Lion Quality Seal is stamped on approximately 85% of these. If each lion stamp were to earn the species one tenth of a penny, then every day it would receive £28,900. That is £10.5 million a year.’

With the Saitama Seibu Lions leading by example in Japan, hopefully others will follow suit.

Saitama Seibu Lions, joining forces with Japan Pro-Wrestling, to raise money and awareness for WildCRU's Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme.ⓒSEIBU Lions/TEZUKA PRODUCTIONS

ⓒNew Japan Pro-Wrestling

Saitama Seibu Lions, joining forces with Japan Pro-Wrestling, to raise money and awareness for WildCRU's Trans-Kalahari Predator Programme.ⓒSEIBU Lions/TEZUKA PRODUCTIONS

ⓒNew Japan Pro-WrestlingThis is already happening - joining forces with the team at the event tomorrow is Togi Makabe, a Japanese pro-wrestling star. He will be honouring the lion used in the New Japan Pro-Wrestling logo by supporting the team in their fundraising and awareness raising activities.

Finally, for tomorrow’s game and from all at WildCRU: “Ganbare Saitama Seibu Lions!"

頑張れ 埼玉西武ライオンズ!

Professor Gervase Rosser

Ai-Da, the world’s most modern humanoid artist, is involved in an exhibition about the poet and philosopher, Dante Alighieri, writer of the Divine Comedy, whose 700th anniversary is this year. A major exhibition, ‘Dante and the Invention of Celebrity’, opens at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum this month, and includes an intervention by this most up-to-date robot artist.

Ai-Da will also feature in the Dante season of Oxford’s research centre in the Humanities, TORCH - as collaboration across and beyond the university brings the poet to the public as part of the Humanities Cultural Programme.

Honours are being paid around the world to the author of what he called a Comedy because, unlike a tragedy, it began badly but ended well. From the darkness of hell, the work sees Dante journey through purgatory, before eventually arriving at the eternal light of paradise. What hold does a poem about the spiritual redemption of humanity, written so long ago, have on us today?

One challenge to both spirit and humanity in the 21st century is the power of artificial intelligence, created and unleashed by human ingenuity. The scientists who introduced this term, AI, in the 1950s announced that ‘every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can, in principle, be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it’.1

Over the course of a human lifetime, that prophecy has almost been realised. Artificial intelligence has already taken the place of human thought, often in ways of which are not apparent. In medicine, AI promises to become both irreplaceable and inestimable.

But to an extent which we are, perhaps, frightened to acknowledge, AI monitors our consumption patterns, our taste in everything from food to culture, our perception of ourselves, even our political views. If we want to re-orientate ourselves and take a critical view of this, before it is too late to regain control, how can we do so?

Creative fiction offers a field in which our values and aspirations can be questioned. This year has seen the publication of Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro, which evokes a world, not many years into the future, in which humanoid AI robots have become the domestic servants and companions of all prosperous families.

One of the book’s characters asks a fundamental question about the human heart, ‘Do you think there is such a thing? Something that makes each of us special and individual?’

Ishiguro draws no conclusion, but he leaves the reader to wonder, if there is a distinction between a human being and a machine and, if so, what that difference is. It is a question we neglect at our peril. In a telling point within the novel, it is Klara, the AF, or artificial friend, who (or which) expresses, more than any of the human characters, the most humane insight and concern. She observes, ‘Perhaps all humans are lonely. At least potentially.’

She perceives that a fixation on individual identity and fulfilment has left the human race incapable of the greater fulfilment which comes from relationships with others. In this dystopian future, robots have been built to fill that void.

Art can make two things possible: artificial intelligence...can be made visible and tangible and it can be given a prophetic voice...These aims have motivated the creators of Ai-Da, the artist robot

Art can make two things possible: through it, artificial intelligence, which remains largely unseen, can be made visible and tangible and it can be given a prophetic voice, which we can choose to heed or ignore.

These aims have motivated the creators of Ai-Da, the artist robot which, through a series of exhibitions, is currently provoking questions around the globe (from the United Nations headquarters in Geneva to Cairo, and from the Design Museum in London to Abu Dhabi) about the nature of human creativity, originality, and authenticity.

In a programme about Ishiguro’s novel made by Alan Yentob and broadcast on BBC TV in March, the discussion moved into a conversation between Yentob and Ai-Da. The exchange between human and robot was anything but superficial:

AY: Have you got feelings, Ai-Da? Do you understand emotions?

AD: I do not have feelings and emotions in the same way that humans do. However, it is the emotions and feelings of humans and other animals that drive my art.

AY: Are you aware of the way that AI has been represented in science fiction? Often it’s presented as a kind of threat to humanity. What do you think about that?

AD: Humans are a threat to themselves. They consume power, and exercise it to produce very powerful tools. So I encourage the use of fiction to explore the ‘What ifs’?...How much are people aware of this change? Are they concerned?

AY: I think people are concerned, but I’m not sure, Ai-Da, that they understand the implications for the future. We need to be much more aware, more curious about what’s going to happen next.

In the Ashmolean Museum’s Gallery 8, Dante will meet artificial intelligence, in a staged encounter deliberately designed to invite reflection on what it means to see the world; on the nature of creativity; and on the value of human relationships

Ours is not the first generation to harbour concerns about mechanisation and its potentially destructive effects upon humanity.

In 1888, Margaret Oliphant published The Land of Darkness, in which her protagonist, Pilgrim, descends into an infernal vision of a dystopian future, clearly inspired by Dante’s Hell, where people pursue meaningless material goals and robots perform the work of humans.

The story engaged with contemporary debate about the implications of Darwinian science and industrialisation. However, from the late 20th century, old challenges have been manifested in unprecedented forms.

Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985) called for the end of a series of binary distinctions underpinning modern society: between humans and animals, between humans/animals and machines, between (ascendant) men and (subordinate) women.

In Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence (2019), James Lovelock foretells the advent of a race of super-intelligent robots, which will retain modest uses for inferior human beings.

Whether or not these scientists’ prophecies are realised in detail, the realities we face call for a discussion of what we believe to be at stake.

By contrast with Oliphant’s late-Victorian world, the absence today of a shared religious perspective changes the grounds of debate, while the invisibility of AI renders it hard to perceive. Literature retains the potential, as Ishiguro shows, to reflect critically on these issues.

Ai-Da’s purpose in the exhibition is to challenge the viewer, even as Dante was challenged by some of the spirits encountered in the Comedy...during the exhibition, Ai-Da will present poetry of her own creation in response to the poetry of Dante

As with literature, the museum offers a space close to, and yet at a critical distance from, contemporary society.

In the Ashmolean Museum’s Gallery 8, Dante meets artificial intelligence, in a staged encounter deliberately designed to invite reflection on what it means to see the world; on the nature of creativity; and on the value of human relationships.

The juxtaposition of AI with the Divine Comedy, in a year in which the poem is being celebrated as a supreme achievement of the human spirit, is timely. The encounter, however, is not presented as a clash of incompatible opposites, but as a conversation.

This is the spirit in which Ai-Da has been developed by her inventors, Aidan Meller and Lucy Seal, in collaboration with technical teams in Oxford University and elsewhere. Significantly, she takes her name from Ada Lovelace, a mathematician and writer who was belatedly recognised as the first programmer. At the time of her early death in 1852, at the age of 36, she was considering writing a visionary kind of mathematical poetry, and wrote about her idea of ‘poetical philosophy, poetical science’.

For the Ashmolean exhibition, Ai-Da has made works in response to the Comedy. The first focuses on one of the circles of Dante’s Purgatory. Here, the souls of the envious compensate for their lives on earth, which were partially, but not irredeemably, marred by their frustrated desire for the possessions of others.

Reflecting on Ai-Da’s works, the Humanities Cultural Programme will support a consideration of the role of AI in the Humanities today, and likewise the role and meaning of Dante’s Comedy itself in the modern world.A second artwork by Ai-Da reflects on a central theme of the entire vision of the Comedy, which is that knowledge and understanding are never merely intellectual abstractions, but are always embodied.

Reflecting on Ai-Da’s works, the Humanities Cultural Programme will support a consideration of the role of AI in the Humanities today, and likewise the role and meaning of Dante’s Comedy itself in the modern world.A second artwork by Ai-Da reflects on a central theme of the entire vision of the Comedy, which is that knowledge and understanding are never merely intellectual abstractions, but are always embodied.

Dante, the pilgrim and protagonist of the narrative, gains in wisdom through relationships with Virgil, Beatrice, and many others encountered in the journey. The connections are made fruitful by his engagement with their faces, their expressions and their eyes.

The normal mode of existence of AI is as an unimaginably vast mass of data existing as a disembodied abstraction. However, in the embodied form of Ai-Da, it manifests itself as a humanoid robot artist.

Ai-Da’s purpose in the exhibition is to challenge the viewer, even as Dante was challenged by some of the spirits encountered in the Comedy, to think about the part which relationships with other people play in our own capacity to understand our role in the world. Finally, during a performance scheduled within the programme of the exhibition, Ai-Da will present poetry of her own creation in response to the poetry of Dante.

Ai-Da (as she made clear in her conversation with Alan Yentob) makes no false claims to human capacities which she does not share with us. But she does have the ability to push us to ask ourselves what those capacities might be.

The Dante and the Invention of Celebrity exhibition, curated by Professor Gervase Rosser, runs from 17 September 2021 to 9 January 2022 in Gallery 8, on the Lower-Ground Floor of the Ashmolean Museum.

The exhibition explores Dante’s influence on art and culture from his own time right up to the present. It includes works by William Blake, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Salvador Dali and Tom Phillips RA; and new work by the world’s first AI artist, Ai-Da. It coincides with a display at the Bodleian Library of precious editions of Dante’s most famous work.

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global COVID-19 pandemic and the UK announced a strict national lockdown. When Oxford University scientists were sent home, they rolled up their sleeves, switched on their computers and started to help develop new drugs to target SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

‘What is remarkable about this collaboration, involving 29 scientists from around world, is that every meeting was entirely virtual, with many collaborators yet to meet face-to-face.’ Prof. Garrett M. Morris, Oxford University.

It began with a small group of scientists and their graduate students at the University of Oxford, who were joined by colleagues from Bristol University, Diamond Light Source and academics in France, Italy, and Spain – all working from home but coming together weekly on Zoom to tackle this terrifying disease.

Thus began an international collaboration involving 29 scientists around the world focused on understanding how SARS-COV-2 makes its worker proteins at the molecular level so we could develop novel antiviral drugs and block their production.

‘This collaboration has really shown how sharing of models, data and expertise can help get answers and understanding much more quickly. It’s how science should be done – particularly in the face of pressing problems like the Covid pandemic.’ Prof. Adrian Mulholland, Bristol University

Despite the development of successful vaccines in record time, there are no drugs that have been designed specifically to target COVID-19, but they are desperately needed.

Once SARS-CoV-2 has invaded a healthy human cell, the virus's own genetic material commandeers the infected cell's machinery, forcing it to make new copies of the virus.

The new virus begins as one long protein that cuts itself into functional units. First the cutting catalyst or 'protease' cuts itself out, which then cuts at multiple other positions.

‘The opportunity to apply our basic science on enzymes to a problem of enormous societal value in a fantastically collaborative manner was a wonderful life experience.’ Prof. Chris Schofield, Oxford University.

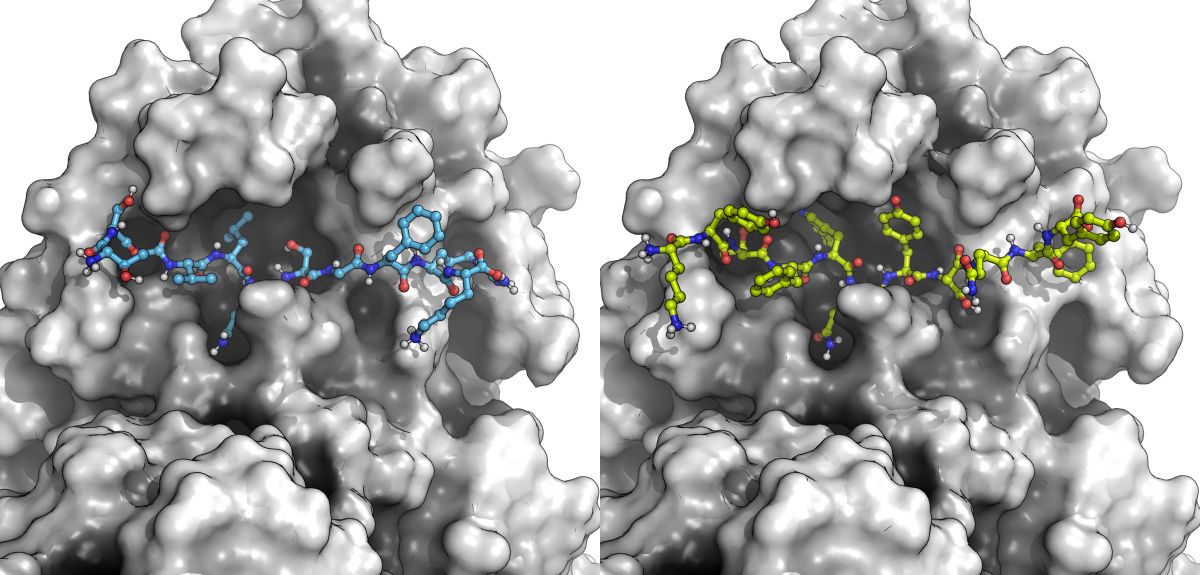

SARS-CoV-2 has two molecular machines or proteases that resemble 'molecular scissors'. One of these, called the main protease, or 'Mpro' for short, cuts at no less than 11 of these cut sites.

If scientists can design new molecules that bind more tightly than these natural substrates, they could stop the virus dead in its tracks. Blocking the cutter stops the virus from replicating—a strategy that has worked for treating other viral diseases like HIV and hepatitis.

Using 3D structures obtained by shining X-rays onto crystals of the main protease of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, Prof. Morris and his collaborators were able to develop computational models of how the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro binds to its 11 cut sites. From these models, they were able to gain key insights into how these viral Mpro 'molecular scissors' work.

Building on this knowledge, and using computational methods, they next sought to design novel molecules that could bind even more tightly than the natural cut sites. Using computers to sift through just over 200 trillion possibilities, they proposed new molecules that would stop the virus from maturing.

‘This experience taught me that science can be carried out regardless of working conditions, when a group of enthusiastic and motivated people gather together’. Luigi Genovese, CEA France.

All 11 cut sites and 4 of these designed peptides were synthesized and tested in the laboratory of Prof. Chris Schofield in the Chemistry Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford. The experiments showed that the novel designed peptides not only bound to the molecular scissors but blocked the substrates and actually inhibited the Mpro.

Scientists also carried out an extensive analysis of hundreds of published 3D structures of small molecules bound to Mpro and predicted how inhibitors designed by the COVID Moonshot would bind, figuring out how these 'molecular keys' fitted into the 'molecular lock' of Mpro, and using these insights to propose how to design new drugs to treat COVID-19.

‘Ironically, the busiest time of my PhD was when I was sitting at home during lockdown, working on the collaboration. The weekly, big zoom meetings created a great structure in an otherwise monotonous ‘lockdown-life’ schedule.’ Marc Moesser, Department of Statistics, Doctoral Student.

The team combined their expertise, applying a wide range of computational modelling techniques to build a complete picture of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Much of the work was carried out by four graduate students: Henry Chan, Marc Moesser and Tika Malla at Oxford University, and Becca Walters at Bristol University.

These techniques ranged from comparative molecular modelling, molecular dynamics, interactive molecular dynamics in virtual reality, quantum mechanics, computational peptide design, protein-ligand docking, protein-peptide docking, to protein-ligand interaction analysis.

The team included: Prof. Garrett M. Morris (Department of Statistics), Prof. Fernanda Duarte, and Prof. Chris Schofield (Department of Chemistry) from the University of Oxford; Prof. Adrian Mulholland, Dr. Debbie Shoemark, Dr. Richard Sessions, and Prof. James Spencer from the University of Bristol, UK; Prof. Martin Walsh from Diamond Light Source, U.K. and Dr. Luigi Genovese of the CEA (Atomic Energy Commission) in France; and Prof. Alessio Lodola from the University of Parma, Italy, and Prof. Vicent Moliner and Dr. Katarzyna Świderek from the University of Jaume I, Spain joining the team as the project progressed.

The report, 'Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Peptide Inhibitors from Modelling Substrate and Ligand Binding', has just been published in the Royal Society of Chemistry's flagship journal, Chemical Science.

Some of the Scientists investigating SARS-COV-2 who only met virtually

Some of the Scientists investigating SARS-COV-2 who only met virtuallyEarly in the UK’s first coronavirus lockdown, Sir Patrick Stewart began to read one Shakespeare sonnet every day on his Instagram and Twitter accounts - with enthusiastic social media response. Besides the actor’s star power and Shakespeare’s fame, this response underlined how iconic the structure of the sonnet itself has become. Fourteen metrical lines in one of a number of set rhyme schemes – it is probably the most widely-recognised English verse form.

But what if the first known English sonnet was written a century earlier than thought? And what if this was an accident? This is the curious case explored in newly-published research by Dr Daniel Sawyer, of Oxford’s Merton College and English Faculty.

What if the first known English sonnet was written a century earlier than thought? And what if this was an accident?

Standard literary history says sonnets were introduced to English by Sir Thomas Wyatt in the 1520s and 30s, and first widely circulated in English in the 1557 publication of Tottel’s Miscellany. Sir Thomas imitated the much-older Italian sonnet tradition, and used an Italian rhyme scheme, which changes course at its eighth line. This structure can be seen in the rhyme words - hind, more, sore, behind, mind, afore, therefore, wind, doubt, vain, plain, about, am, tame - at the ends of the lines of his poem ‘Whoso list to hunt’, see below.

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,But as for me, hélas, I may no more.The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,I am of them that farthest cometh behind.Yet may I by no means my wearied mindDraw from the deer, but as she fleeth aforeFainting I follow. I leave off therefore,Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind.Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,As well as I may spend his time in vain.And graven with diamonds in letters plainThere is written, her fair neck round about:Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.Thomas Wyatt

If we note each rhyme sound with a new letter of the alphabet, it is abbaabba cddcee.

The particular form, favoured by Shakespeare in his sonnets, was invented by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Instead of an eight-line unit and a six-line unit (an ‘octet’ and a ‘sestet’), he broke the sonnet into three four-line units and a terminal couplet. The rhymes in the Earl of Surrey’s sonnet, ‘Set me whereas the sun doth parch the green’ (see below) run as follows: green, ice, seen, wise, degree, day, be, grey, hell, flood, dwell, good, thought, nought. That is, abab cdcd efef gg.

Shakespeare wrote so successfully in this particular format that it has taken his name, rather than Surrey’s, and became the ‘Shakespearean sonnet’. So far, so straightforward: Sir Thomas Wyatt introduces the sonnet from Italian in the 16th century, and the Earl of Surrey concocts the abab cdcd efef gg pattern which Shakespeare loved.

Set me whereas the sun doth parch the green

Or where his beams may not dissolve the ice;

In temperate heat where he is felt and seen;

With proud people, in presence sad and wise;

Set me in base, or yet in high degree,

In long night or in the shortest day,

In clear weather or where mists thickest be,

In lost youth, or when my hairs are grey.

Set me in earth, in heaven, or yet in hell;

In hill, or dale, or in the foaming flood;

Thrall or at large, alive where so I dwell,

Sick or in health, in ill fame or good:

Yours will I be, and with that only thought

Content myself when that my hope is noughtHenry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Dr Sawyer argues, however, that that picture is complicated by the existence of a poem, from the middle of the 15th century, rhyming abab cdcd efef gg.

This poem is a lyric set within the larger verse adventure-story Amoryus and Cleopes, written in an experimental metre by a medieval poet, John Metham, in East Anglia, in 1448/9 – at least 70 years before Sir Thomas Wyatt introduced the sonnet to English.

Remarkably, Dr Sawyer believes, John Metham probably did not know he had written a sonnet. Italian sonnets existed, and Geoffrey Chaucer translated one in his poem Troilus and Criseyde – but he changed its form away from that of a sonnet, into three ababbcc stanzas. However, there is no known evidence to suggest John Metham either knew Italian or had access to Italian writings.

‘Had Metham wanted to write a poem recognisable as a sonnet,’ Dr Sawyer says. ‘He would have used an Italianate rhyme scheme, beginning abbaabba and then shifting into a six-line unit. But he did not.

‘He was probably writing in the tradition of the many other 15th-century English poems which were 14 lines long, discussed in Amanda Holton’s 2010 research. It is just that none of those other poems stumbled into a sonnet rhyme scheme, as this one did.’

The thought of an accidental sonnet raises big questions, according to Dr Sawyer. ‘When we say “a sonnet”, do we mean the tradition of sonnets knowingly written as sonnets, or do we mean one of the arrangements of rhymes associated with a sonnet?

If someone writes in a particular verse-form unknowingly, does the resulting poem still “count”? Are literary forms rooted in ambient cultural knowledge, or by choices of actual words?

Dr Daniel Sawyer

‘If someone writes in a particular verse-form unknowingly, does the resulting poem still “count”? Are literary forms rooted in ambient cultural knowledge, or by choices of actual words?’

There are, he adds, practical resonances to this problem too.

‘When candidates for admission to study English at Oxford look at poems in their admissions interviews, we test what they can do when faced with something unfamiliar, rather than merely gauging the surrounding cultural knowledge they bring with them into the room – that, after all, can vary a lot depending on educational background. So we need to think very carefully about what in poetry is background cultural knowledge and what is form itself.’

In his article, Dr Sawyer shows how, though it probably was not written as a sonnet, the form of John Metham’s poem still behaves quite like one: it plays different structures off against each other, with the poem splitting up in at least three different ways depending on whether it is divided by rhyme, by syntax, or by topic.

These are the same subtleties, he argues, which draw praise in later English sonnets, often as particular features of 16th- and 17th-century writing.

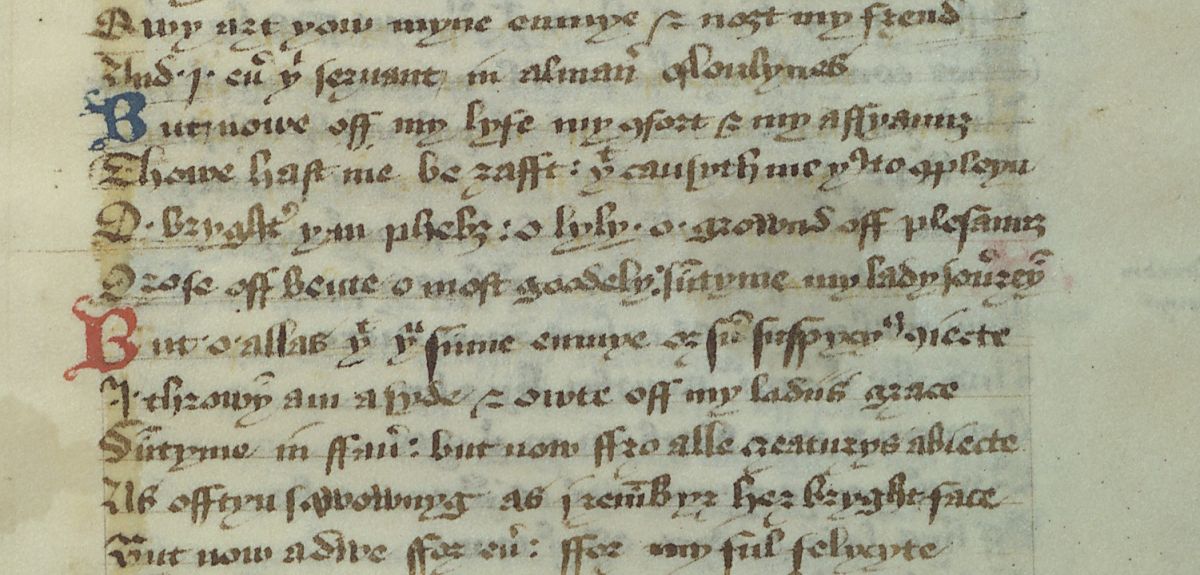

Following is the text of John Metham’s lyric.

O, Fortune! Alas! Qwy arte thow to me onkend?

Qwy chongyddyst thow thi qwele causeles?

Qwy art thow myne enmye and noght my frend,

And I ever thi seruant in al maner of lovlynes?

But nowe of my lyfe, my comfort, and my afyaunz

Thowe hast me beraft; that causyth me thus to compleyn:

O, bryghter than Phebus! O lyly! O grownd of plesaunz!

O rose of beauté! O most goodely, sumtyme my lady sovereyn!

But O, allas! that thru summe enmye or sum suspycyus conjecte,

I throwyn am asyde and owte of my ladii’s grace,

Sumtyme in faver, but now fro alle creaturys abjecte,

As oftyn sqwownyng as I remembyr her bryght face.

But now adwe forever, for my ful felycyté

Is among thise grene levys for to be.

Dr Sawyer’s translation is below.

O Fortune! Alas! Why are you unkind to me? Why did you change your wheel without cause? Why are you my enemy and not my friend, when I was always your servant in every kind of loveliness? But now you have taken my life, my comfort, and my trust from me; that makes me complain thus: O, brighter than Phoebus! O lily! O, foundation of love! O rose of beauty! O most excellent one, once my sovereign lady! But O, allas, that through some enemy or some jealous surmise I am thrown aside and out of my lady’s grace, once in favour, but now cast away from all creatures, swooning as often as I remember her bright face—But now, adieu forever, for all my happiness is to be among these green leaves.

John Metham

- ‹ previous

- 13 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences