The mystery of the ‘first’ English sonnet.

Early in the UK’s first coronavirus lockdown, Sir Patrick Stewart began to read one Shakespeare sonnet every day on his Instagram and Twitter accounts - with enthusiastic social media response. Besides the actor’s star power and Shakespeare’s fame, this response underlined how iconic the structure of the sonnet itself has become. Fourteen metrical lines in one of a number of set rhyme schemes – it is probably the most widely-recognised English verse form.

But what if the first known English sonnet was written a century earlier than thought? And what if this was an accident? This is the curious case explored in newly-published research by Dr Daniel Sawyer, of Oxford’s Merton College and English Faculty.

What if the first known English sonnet was written a century earlier than thought? And what if this was an accident?

Standard literary history says sonnets were introduced to English by Sir Thomas Wyatt in the 1520s and 30s, and first widely circulated in English in the 1557 publication of Tottel’s Miscellany. Sir Thomas imitated the much-older Italian sonnet tradition, and used an Italian rhyme scheme, which changes course at its eighth line. This structure can be seen in the rhyme words - hind, more, sore, behind, mind, afore, therefore, wind, doubt, vain, plain, about, am, tame - at the ends of the lines of his poem ‘Whoso list to hunt’, see below.

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,But as for me, hélas, I may no more.The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,I am of them that farthest cometh behind.Yet may I by no means my wearied mindDraw from the deer, but as she fleeth aforeFainting I follow. I leave off therefore,Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind.Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,As well as I may spend his time in vain.And graven with diamonds in letters plainThere is written, her fair neck round about:Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.Thomas Wyatt

If we note each rhyme sound with a new letter of the alphabet, it is abbaabba cddcee.

The particular form, favoured by Shakespeare in his sonnets, was invented by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Instead of an eight-line unit and a six-line unit (an ‘octet’ and a ‘sestet’), he broke the sonnet into three four-line units and a terminal couplet. The rhymes in the Earl of Surrey’s sonnet, ‘Set me whereas the sun doth parch the green’ (see below) run as follows: green, ice, seen, wise, degree, day, be, grey, hell, flood, dwell, good, thought, nought. That is, abab cdcd efef gg.

Shakespeare wrote so successfully in this particular format that it has taken his name, rather than Surrey’s, and became the ‘Shakespearean sonnet’. So far, so straightforward: Sir Thomas Wyatt introduces the sonnet from Italian in the 16th century, and the Earl of Surrey concocts the abab cdcd efef gg pattern which Shakespeare loved.

Set me whereas the sun doth parch the green

Or where his beams may not dissolve the ice;

In temperate heat where he is felt and seen;

With proud people, in presence sad and wise;

Set me in base, or yet in high degree,

In long night or in the shortest day,

In clear weather or where mists thickest be,

In lost youth, or when my hairs are grey.

Set me in earth, in heaven, or yet in hell;

In hill, or dale, or in the foaming flood;

Thrall or at large, alive where so I dwell,

Sick or in health, in ill fame or good:

Yours will I be, and with that only thought

Content myself when that my hope is noughtHenry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Dr Sawyer argues, however, that that picture is complicated by the existence of a poem, from the middle of the 15th century, rhyming abab cdcd efef gg.

This poem is a lyric set within the larger verse adventure-story Amoryus and Cleopes, written in an experimental metre by a medieval poet, John Metham, in East Anglia, in 1448/9 – at least 70 years before Sir Thomas Wyatt introduced the sonnet to English.

Remarkably, Dr Sawyer believes, John Metham probably did not know he had written a sonnet. Italian sonnets existed, and Geoffrey Chaucer translated one in his poem Troilus and Criseyde – but he changed its form away from that of a sonnet, into three ababbcc stanzas. However, there is no known evidence to suggest John Metham either knew Italian or had access to Italian writings.

‘Had Metham wanted to write a poem recognisable as a sonnet,’ Dr Sawyer says. ‘He would have used an Italianate rhyme scheme, beginning abbaabba and then shifting into a six-line unit. But he did not.

‘He was probably writing in the tradition of the many other 15th-century English poems which were 14 lines long, discussed in Amanda Holton’s 2010 research. It is just that none of those other poems stumbled into a sonnet rhyme scheme, as this one did.’

The thought of an accidental sonnet raises big questions, according to Dr Sawyer. ‘When we say “a sonnet”, do we mean the tradition of sonnets knowingly written as sonnets, or do we mean one of the arrangements of rhymes associated with a sonnet?

If someone writes in a particular verse-form unknowingly, does the resulting poem still “count”? Are literary forms rooted in ambient cultural knowledge, or by choices of actual words?

Dr Daniel Sawyer

‘If someone writes in a particular verse-form unknowingly, does the resulting poem still “count”? Are literary forms rooted in ambient cultural knowledge, or by choices of actual words?’

There are, he adds, practical resonances to this problem too.

‘When candidates for admission to study English at Oxford look at poems in their admissions interviews, we test what they can do when faced with something unfamiliar, rather than merely gauging the surrounding cultural knowledge they bring with them into the room – that, after all, can vary a lot depending on educational background. So we need to think very carefully about what in poetry is background cultural knowledge and what is form itself.’

In his article, Dr Sawyer shows how, though it probably was not written as a sonnet, the form of John Metham’s poem still behaves quite like one: it plays different structures off against each other, with the poem splitting up in at least three different ways depending on whether it is divided by rhyme, by syntax, or by topic.

These are the same subtleties, he argues, which draw praise in later English sonnets, often as particular features of 16th- and 17th-century writing.

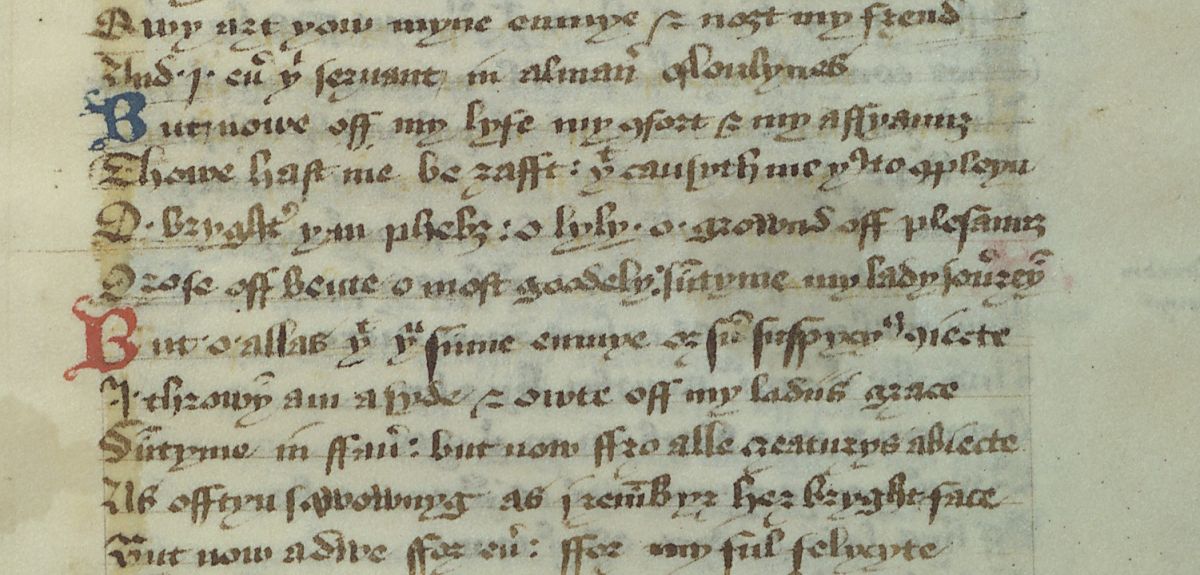

Following is the text of John Metham’s lyric.

O, Fortune! Alas! Qwy arte thow to me onkend?

Qwy chongyddyst thow thi qwele causeles?

Qwy art thow myne enmye and noght my frend,

And I ever thi seruant in al maner of lovlynes?

But nowe of my lyfe, my comfort, and my afyaunz

Thowe hast me beraft; that causyth me thus to compleyn:

O, bryghter than Phebus! O lyly! O grownd of plesaunz!

O rose of beauté! O most goodely, sumtyme my lady sovereyn!

But O, allas! that thru summe enmye or sum suspycyus conjecte,

I throwyn am asyde and owte of my ladii’s grace,

Sumtyme in faver, but now fro alle creaturys abjecte,

As oftyn sqwownyng as I remembyr her bryght face.

But now adwe forever, for my ful felycyté

Is among thise grene levys for to be.

Dr Sawyer’s translation is below.

O Fortune! Alas! Why are you unkind to me? Why did you change your wheel without cause? Why are you my enemy and not my friend, when I was always your servant in every kind of loveliness? But now you have taken my life, my comfort, and my trust from me; that makes me complain thus: O, brighter than Phoebus! O lily! O, foundation of love! O rose of beauty! O most excellent one, once my sovereign lady! But O, allas, that through some enemy or some jealous surmise I am thrown aside and out of my lady’s grace, once in favour, but now cast away from all creatures, swooning as often as I remember her bright face—But now, adieu forever, for all my happiness is to be among these green leaves.

John Metham

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools