Features

Even though nobody in her family had been to university before, Jaycie Carter dreamed of studying English at Oxford.

And, now that she’s here, she’s making sure that all students who study here feel comfortable regardless of their background.

Jaycie is part of a team, led by Oxford University Student Union (OUSU), that set up Class Act, a new campaign that aims to support working class, low income, state comprehensive and first-generation students.

“I’d been thinking a lot about class, and writing about it for my English degree, and I thought it would make such a difference for students like me to have a place where they could meet, talk, and discuss the issues that we face,” Jaycie says.

From a young age, Jaycie, who is from the West Midlands, enjoyed studying, using English and psychology to explore the history of ideas and society.

“I knew I wanted to go to university, cause I’ve always been quite academic and read a lot,” she says.

Jaycie hoped to go to Oxford, and now that she’s here, she’s relishing all the city offers.

“It was the dream, so it’s a bit weird actually being here now. Sometimes I have to remind myself—it’s really cool that I’m here!” she says.

Outside of her English degree, she’s also an active member of the LGBTQ community.

“I really like my course, and studying areas I’m interested in, like class and sexuality,” she says. “And the LGBTQ community is great, we have so many resources and events happening every week.”

Being part of the LGBTQ community made Jaycie think about how valuable it would be to have a similar community for students from working-class backgrounds.

“I saw how helpful it is to meet with other people who are similar to you,” she says. She wanted to foster the same sense of community for working-class and state-educated students who, like her, can face a unique set of challenges when they arrive at university.

“It can sometimes be alienating if you or your family don’t have much experience of higher education,” she says.

So, when she heard about a new campaign for working-class students that was in the pipeline, Jaycie got involved. The campaign launched in May 2017, and Jaycie was elected co-chair. Now, she’s excited to get started.

“It’s important to give people spaces to acknowledge the things they face. My aim is to create the things I needed when I got here,” she says.

The campaign has four strands: working class, state comp, low income, and first generation. Any student who identifies with any of the strands is welcome to get involved. “We want to make our campaign as broad and welcoming as we can. We’re not try to define what it means to be working class,” Jaycie says.

Since the launch, the campaign has held a social, and there are plenty more plans in place. This includes speaker events and a survey that will ask students what they’d like to see from the campaign.

With a team of reps—which represent the diverse experiences and identities of students in Oxford—the committee ran four social events last term, as well further events such as an LGBTQ meet up and a social for students from state comprehensives.

They’re also hoping to create an academic guide, which will give students access to information they might not have been made aware of before they arrive, and to run careers events, in which alumni from Class Act backgrounds will come and chat about their experiences and offer students the opportunity to network.

Jaycie is excited to be part of a committee that will complement all of the positive access work that Oxford does by creating support systems for students once they arrive.

And her efforts are already paying off. “The reception has been amazing. Lots of people have said it’s great that the problems they’ve faced are being acknowledged and discussed,” she says.

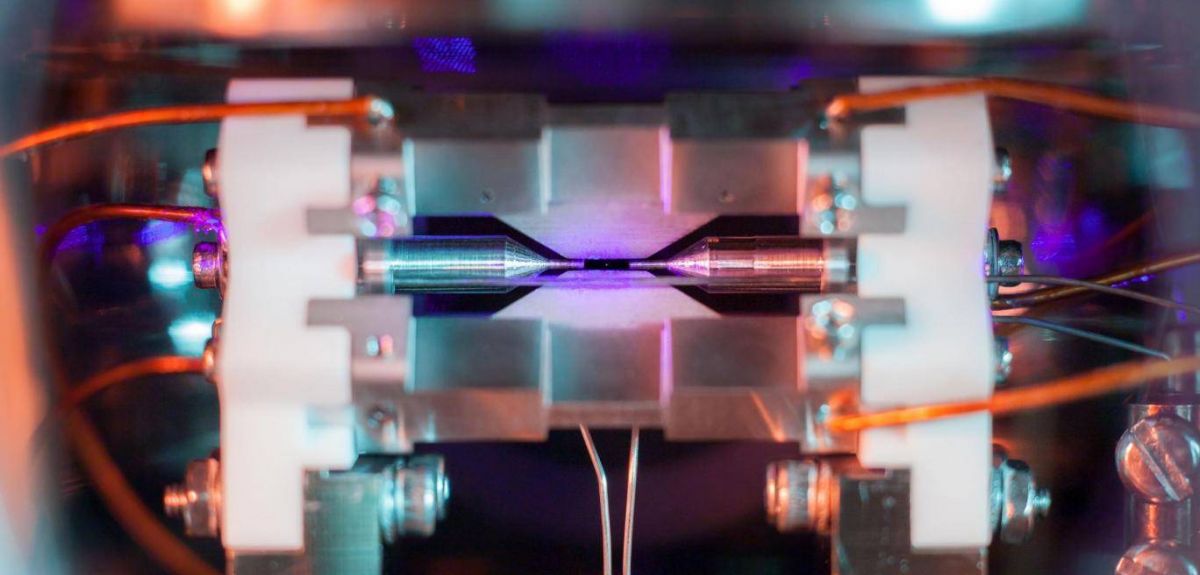

An image of a single positively-charged strontium atom, held near motionless by electric fields, has won the overall prize in a national science photography competition, organised by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

‘Single Atom in an Ion Trap’, by David Nadlinger, from the University of Oxford, shows the atom held by the fields emanating from the metal electrodes surrounding it.

The distance between the small needle tips is about two millimetres. When illuminated by a laser of the right blue-violet colour the atom absorbs and re-emits light particles sufficiently quickly for an ordinary camera to capture it in a long exposure photograph.

The winning picture was taken through a window of the ultra-high vacuum chamber that houses the ion trap. Laser-cooled atomic ions provide a pristine platform for exploring and harnessing the unique properties of quantum physics.

They can serve as extremely accurate clocks and sensors or, as explored by the UK Networked Quantum Information Technologies Hub, as building blocks for future quantum computers, which could tackle problems that stymie even today’s largest supercomputers. The image, came first in the Equipment & Facilities category, as well as winning overall against many other stunning pictures, featuring research in action, in the EPSRCs competition – now in its fifth year.

David Nadlinger explained how the photograph came about: “The idea of being able to see a single atom with the naked eye had struck me as a wonderfully direct and visceral bridge between the miniscule quantum world and our macroscopic reality," he said.

"A back-of-the-envelope calculation showed the numbers to be on my side, and when I set off to the lab with camera and tripods one quiet Sunday afternoon, I was rewarded with this particular picture of a small, pale blue dot.”

Names, dates, bad jokes, life advice: we find graffiti almost everywhere in modern life.

But not many people realise that scrawling on walls isn’t anything new. At least three thousand years ago, in the dusty heat of Ancient Egyptian temples, people did the very same thing.

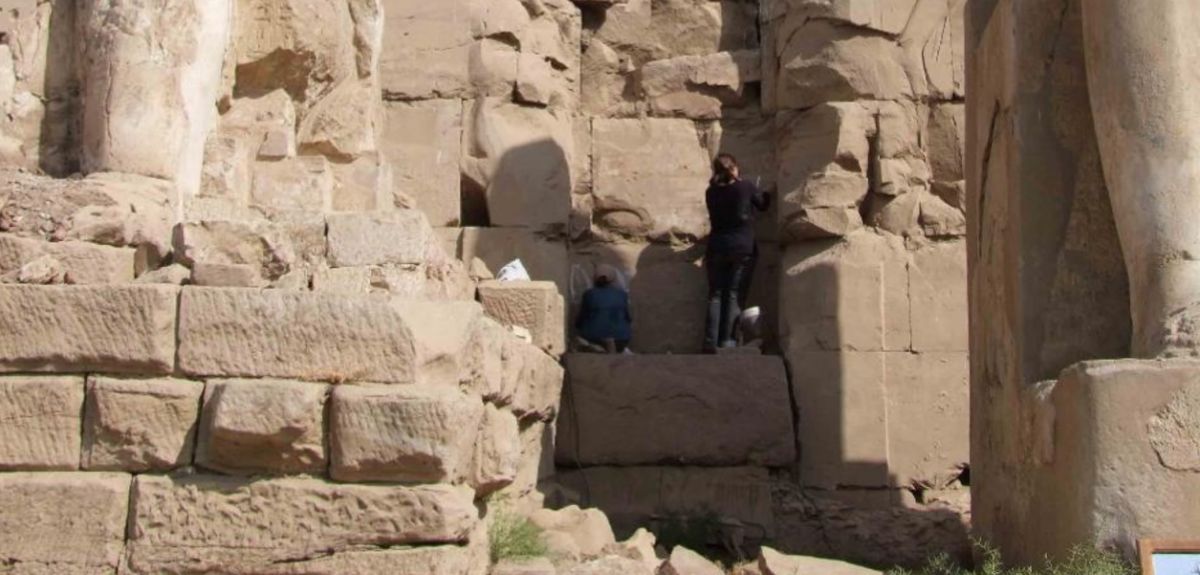

Dr. Elizabeth Frood, Associate Professor of Egyptology, has been painstakingly uncovering examples of such graffiti at the four-thousand-year-old Temple of Karnak.

Nestled alongside official images of the gods are the names and drawings of ordinary people. Some are carved into sandstone, while others have been carefully inked and painted.

“People write their names and titles—sort of like “I was here”,” Dr. Frood explains. “A lot of the graffiti is by temple staff. In one stairwell, we have a baker’s name and image—I imagine him as someone who made delicious cakes for the gods.”

Unlike some of the more unsavoury graffiti you might stumble across nowadays, however, our ancient contemporaries appear to have been quite inspired by religion.

“People always ask me, “Ooh, is there obscenity?” And I have to admit, “No, they’re really pious!”” Dr. Frood says.

But this doesn’t mean that the graffiti were always accepted. In some cases, Dr. Frood has discovered that it had been plastered over or even erased, although sometimes, just like today, this was simply to make room for more graffiti.

“You look at it, and you know there’s something different about it, a bit jarring. You can imagine priests or officials walking through, seeing it, and thinking, “Weird!””.

Dr. Frood first noticed the graffiti during her own doctorate, when she was researching formal temple displays.

“I remember walking through the temple, looking at all the formal inscriptions. And then, suddenly, it was like looking through a kaleidoscope—something shifted, and all of this graffiti popped out of the wall!”

The graffiti had been there all along. “I’d been a student pottering around in this temple, and I’d not noticed, and then suddenly my lens changed—and it was everywhere!”

Dr. Frood carried on with her doctorate, but she didn’t forget the graffiti. When the chance to work on it finally popped up, in 2010, she grabbed it.

Researching graffiti is hard work. In collaboration with the Centre Franco-Égyptien d’Études de Temples de Karnak, Dr. Frood and her doctoral student, Chiara Salvador, have been meticulously photographing, copying, and analysing the inscriptions. They then try to date it by examining the style of handwriting and the surrounding archaeology.

But such thorough work means that Dr. Frood has the opportunity to connect with people who lived thousands of years ago.

“When you’re recording a graffito, and tracing someone’s name, you’re following the hand of someone that was writing on the temple wall in, say, 1100 BC. And on an emotional level, that’s very powerful.”

And documenting this graffiti gives us an unusual peek into daily life of an ancient society.

“We’re accessing the day-to-day,” Dr. Frood says. “You can begin to imagine this busy, bustling temple environment—people doing building work, performing rituals, cleaning up.

“The moment you shift your lens, the temple becomes this cluttered, busy, bustling, human space. It’s often hard for us to imagine what these environments would’ve felt like, but the graffiti lets us do that. And that’s what makes them so special.”

More than 20 Oxford colleges and departments flew a flag to celebrate the 100 year anniversary of women’s suffrage today (Tuesday 6 February).

It is the centenary of the Representation of the People’s Act, which granted the vote to women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification. The same Act gave the vote to and enfranchised all men over the age of 21 for the first time.

The event was organised by TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities), in collaboration with city and county Council representatives, and other cultural organisations in the city. It marks the launch of a year-long programme of initiatives including exhibitions and public lectures.

The flag flew proudly above 21 University of Oxford Colleges, along with the Humanities Division in Radcliffe Humanities (originally the Radcliffe Infirmary), the Music Faculty and the Rothermere American Institute, the County and Town Halls, Modern Art Oxford, Shepherd & Woodward, and Oxford Castle.

The flags read ‘Votes for Women’, which was printed on a backdrop of purple, white and green – the colours of the Women's Social and Political Union, which was led by Emmeline Pankhurst.

Do you speak Latin? You probably do. If you’ve ever used a memo, or got a train via London, or watched Arsenal versus Watford, you’re a bona fide speaker.

Latin is everywhere, even though most of us don’t learn it at school. But researchers in the Classics in Communities project, based in the Classics Faculty, have been exploring how learning Latin at a young age can impact children’s cognitive development.

“There are so many benefits of learning Latin,” Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson, a researcher in the project, says. “As well as being an interesting curriculum subject in its own right, it can also support the development of literacy skills and critical skills.”

As part of her research, she has been tracking groups of primary school students in Scotland, the West Midlands, Oxfordshire and London. She has gathered data about students’ reading and writing proficiency before and after they learn Latin.

And she says that learning Latin helps children in other areas of life. “Our data definitely supports the hypothesis that learning Latin in primary school is a good educational choice,” she says.

The researchers have looked closely at socially and economically disadvantaged areas. There, they’ve found that learning Latin can have even more of a positive impact. “In these schools, learning Latin can make a significant difference to learners’ progress,” Dr Holmes-Henderson says.

And it’s not just academic—learning Latin can also help children develop cultural literacy, which enriches their understanding of the contemporary world by making them familiar with classical references. Has anyone ever told you to carpe diem? There’s that Latin again, encouraging you to seize the day.

There may be plenty to gain from learning Latin, but many children simply don’t get the opportunity to have a go at it. This is another area where Classics in Communities provides help.

“Since 2014, when Latin and Greek were named in the English National Curriculum as languages suitable for study in primary schools, we have been running training courses and providing support for primary school teachers around the UK,” Dr Holmes-Henderson explains.

Through the project website, Classics in Communities has been providing resources for teachers who have little experience of Latin themselves. This way, they hope that more and more primary school children will have the opportunity to learn.

And Latin can also be a lot of fun. “The legacy of the Romans encompasses literature, art, architecture, philosophy, history and language," says Dr Holmes-Henderson.

"Learning Latin helps young people begin to discover what life was like for the Romans. Graffiti from the walls of Pompeii are short and relatively simple, so even at primary school level, children can engage with some real Latin.”

If you like the sound of that, carpe diem, and try some Latin for yourself. Remember, audaces fortuna iuvat – fortune favours the brave.

Dr Holmes-Henderson’s book, Forward with Classics: Classical languages in schools and communities, will be published by Bloomsbury Academic this year (co-edited with Steven Hunt and Mai Musie).

- ‹ previous

- 81 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?