Features

The Cut Out Girl by Oxford English professor Bart van Es has been named Costa Book of the Year, after previously winning the biography category of the awards. Professor van Es triumphed ahead of literary figures including novelist Sally Rooney. Read our Q&A below with Professor van Es, whose book tells the story of Lien de Jong, a young Dutch girl hidden from the Nazis during World War II.

*************************************************************************************************

The last time Lien de Jong saw her parents was in the Hague, where she was collected at the door by a stranger and taken away to be hidden from the Nazis. She was raised by her foster family as one of their own, but a falling out after the war put an end to their relationship. What was her side of the story, wondered Oxford University's Professor Bart van Es, a grandson of the couple who looked after Lien.

Professor van Es, of St Catherine's College and Oxford's English Faculty, talks to Arts Blog about the journey that led to the publication of his new book, The Cut Out Girl: A Story of War and Family, Lost and Found.

How did you discover the story of Lien de Jong?

I had always known that my grandparents had been part of the Dutch wartime resistance and had sheltered Jewish children, but I had never looked into what actually happened. Then in November 2014 my eldest uncle died and I knew that if I did not pursue the matter now this history would be lost forever. Thanks to my mother’s maintaining of an old connection, I got to meet Lien, who was by that time over 80 and living in Amsterdam. As a young Jewish girl Lien had lived in hiding with my grandparents and after the war she had continued to live with them. However, a row in the 1980s had cut her off from the family, which meant that she and I had never met. Lien was cautious when we met in late December 2014, but, once trust was established, we struck up a powerful partnership. Lien agreed to work with me and shared a wealth of materials: letters, photographs, official documents, and also a poetry book that she kept up throughout the war. Through many tens of hours of recorded interviews, Lien shared a story that was immensely moving and far more complex than I could have imagined.

Can you describe the process of researching and writing the book?

Starting out from those interviews with Lien, this became an archival research project as well as a literary journey. In January 2015 I decided to visit the places of Lien’s childhood: her parents’ home in The Hague (now a physiotherapy gym), my grandparents' old address in Dordrecht (now in a deprived area inhabited mainly by recent immigrants), and a series of other hiding addresses across the Netherlands, including my mother’s home village, where Lien spent time. These places brought their own stories, which I then began to investigate. Among other things I spent a lot of time at the Dutch National Archives looking at the prosecution material on 230 Dutch police officers who were investigated after the war for their role in the Holocaust. What I ended up with was a huge amount of material: the intimate narrative of Lien’s life from childhood to old age combined with archival evidence on resistance networks, police collaboration, and the wider history of Jews in the Netherlands. The challenge was to put this into a single book.

How easy was it to combine academic research with such a personal story?

It was challenging to combine the two kinds of material I had to hand, and I had some sleepless nights over what I was doing. After various experiments I opted for a double narrative with one strand in the first person (describing my travels and the documentary evidence I encountered) and a second strand that was much more novelistic (written in the third person, voicing the childhood experiences of Lien). I’d never written in such an emotionally intense way before. It was exciting and all-consuming. At the same time it was important to remain academically objective: there could be no factual errors about what happened in the war and afterwards, both because of its historical importance and because there were real, still-living people involved.

Are there any moments from your conversations with Lien that particularly stand out?

The things that stand out for me are the documents that Lien has kept with her. For example, there is the letter that Lien’s mother wrote to my grandparents in August 1942, in which she gave up her child in the hope that Lien would survive the war even if the rest of the family could not. There is also the last letter that Lien ever wrote to her mother, which was not delivered because her parents were already in Auschwitz by the time it would have been sent via the secret post. Also very powerful are the wider stories of resistance activity that came to me in the course of my research. In one case a group of young Dutch women decided that the only way in which they could save Jewish babies would be to claim them as their own illegitimate children, fathered by German soldiers. This brought absolute safety to the babies, but also, of course, terrible shame to the women themselves.

In the book I try to answer some big questions, including:

- Why was the Netherlands so compliant with the Nazis, so that 80% of the country’s Jews were killed, a far higher percentage than elsewhere in the West?

- What was it that made some brave people (such as my grandparents) resist the Nazis?

- What were the psychological consequences for survivors and rescuers?

- And, most pressingly as far as The Cut Out Girl story is concerned, how could my grandmother (who rescued Lien and brought her up as her own daughter after the war) have ended up quarrelling with the person she saved from the Holocaust? How could she have sent her a letter, in July 1988, that cut Lien out of her life?

Answering those questions will, I hope, give a new perspective on what happened in World War II.

The Cut Out Girl by Bart van Es is published by Fig Tree, 2 August, priced £16.99.

Kristiina Visakorpi, a doctoral researcher in Oxford’s Department of Zoology, sheds light on her work studying insect herbivores and the effect that they have on plant processes such as photosynthesis, their carbon emission levels and the potential long-term implications for the environment.

Almost every plant will be eaten by an insect at some point in its life. While the damage caused by plant-feeding insects is understood to impact the functioning or structure of plants and trees, we still know very little about how these changes affect larger-scale plant processes and the canopy ecosystems that they are part of.

The role of insects is usually not taken into account when estimating fluxes of carbon between forests and the atmosphere, or when predicting how changes in the climate might affect the intake of carbon by plants. However, our new study, published in the journal New Phytologist looks at how insects feeding on oak leaves can affect both the photosynthetic rate of these leaves, and whether or not these changes can alter the amount of carbon being absorbed by the tree.

We studied winter moth caterpillars, which are a common insect species that feeds on leaves of many trees, including those in Wytham Woods, Oxford. We found that the photosynthetic rate is substantially lower on leaves that have either been eaten by caterpillars, or on uneaten leaves, growing next to these leaves.

Next, we looked at how many eaten leaves there are in the oak canopy, compared to completely uneaten leaves surrounded only by other uneaten leaves. When we take into account the leaf-level changes, and the proportion of these different leaves in the canopy, we estimate that half of the potential photosynthesis on a level of the canopy is lost. This means that even a small amount of damage caused by caterpillars on an individual leaf, adds up to a huge amount of carbon not being assimilated through photosynthesis across the whole tree.

With the warming climate, many insect species are predicted to spread to new areas, or increase in abundance. If the effects we found in our experiment hold for other tree and insect species, the changing climate, through changing the ranges and abundances of insect populations, can alter how well the forests take up carbon in the future. Unless the effects we have measured are taken into account in climate predictions, the outcomes of these predictions might be misleading.

Earlier this year our research featured in the BBC documentary Judi Dench: My passion for trees.

Over the coming months we will explore if other oak leaf traits change simultaneously with the photosynthetic rate. This will involve measuring the chemistry of the leaves to see if the tree is producing defensive chemicals to protect itself from the caterpillars, which might be taking up resources needed for photosynthesis. We also aim to understand exactly how much carbon is being lost through a lowered seasonal rate of photosynthesis, and on the scale of the whole forest.

If you listen to Piers Morgan, Love Island, the reality TV programme that has had 3.4 million people hooked night after night this summer, is for the ‘uneducated’ and ‘dim-witted’.

However, writing for the Daily Mirror this week, as part of her British Science Association Media Fellowship placement, Dr Holly Reeve of Oxford University’s Department of Inorganic Chemistry, revealed that fans of the show have more in common with professional scientists than you might expect.

Do your evenings involve:

- predicting who will find who attractive?

- studying contestants 'impressive' approaches to coupling up?

- wondering what will happen when more men or women are introduced?

- marvelling over the response of individuals to the latest dramatic twist?

Sounds like you're a scientist. An evolutionary biologist to be precise.

Dr Stuart Wigby and his team at the University of Oxford literally watch flies mating to study everything from reproduction and fertility, to changes in female behaviour (including aggression) after sex, to the link between sex, aging and number of sexual partners.

So, what can Love Island fans learn from science - and just as importantly, can the scientists learn anything from Love Island?

One of the biggest similarities between fly sex research and Love Island is the ability to control sex bias in populations (or on islands). That means that you can study the effect of having more males or females in a population on an individual's behaviour.

However, it's worth remembering that flies have very different concerns to their Love Island counterparts.

Sally Le Page from the Wigby lab says for flies, mating ‘is all about the number of offspring’, you can produce with no concern about the morality of partnerships.

In Love Island, to survive the public vote, ‘contestants effectively have to pair up in ways in which the watching public approve!’

But it's these very different concerns that make Love Island interseting.

So, what can we learn from Love Island?

Love Island essentially sets up and enforces sequential monogamy - that is, to survive (stay on the island) you need to be a couple.

It's a different setup from an evolutionary perspective where the costs and benefits of mating are different for men and women.

Dr Wigby says Love Island ‘makes the costs and benefits equal for both sexes’.

‘You might expect males and females to become more similar in behaviour...and, over evolutionary time, appearance too’.

Yikes!

Of course, things are a bit different when nature and evolution come in to play.

As Empirical Zeal explains; when it comes to flies: ‘Sex is war. It's a battle for limited resources.

"The source of sexual conflict is this: sperm is a relatively cheap resource for males to produce, whereas producing eggs and rearing offspring is a much larger investment on the part of the female.’

Which is where some of the conflict comes from on ITV each night - contestants bucking the evolutionary trend in order to win the contest.

We know how to study Love Island, but how do you study fly sex.

Studying fly sex and studying Love Island have some similarities (and some differences).

Male and female Drosophila melanogaster flies can be identified by their bottoms. Females tend to have large light coloured behinds, whereas males have smaller black ones.

From a selection of flies, you can separate them into compartments at male to female ratios of your choice... using small paint brushes (so the flies don't get damaged)!

From there, you can sit, watch and wait.

Studying fly behaviour

And you'll see the flies starting to mate.

Dr Wigby says: ‘It usually takes them around 20 minutes" (impressive) "so realistically you don't have to check in on them too often.'

Number of mates, fly behaviour, number of eggs laid and number of baby flies hatched can all be carefully monitored.

All in the time it takes to watch an episode (or perhaps two) of our favourite show.

Two fruit flies mating.

Two fruit flies mating.Image credit: Amy Hong

Why do scientists study fly sex?

Flies are a good model to study for a number of reasons.

Firstly, they have short life cycles, and therefore evolution can be studied much more easily than in larger animals or humans.

Secondly, particular species of flies (like Drosophila melanogaster ) are really well understood at a genetic level. That means that it's much easier to relate findings to actual genetic changes.

Lastly, it's not particularly ethical to study these things in humans, unless it's broadcast on TV...

What have we learnt from insect sex research, past, present and future?

We've learnt a lot from studying mating in animals, including in flies and other insects.

For example, there's research that says sex can alter female behaviour.

That's because ejaculate contains a cocktail of proteins alongside sperm. These proteins can lead to emotional, and over time evolutionary, changes to females. In one Wigby group study 'when males were exposed to a competitor male, matings were longer' and more of two particular sex proteins were transferred to the females. And in another, sex led to a significant increase in aggression of female flies when it came to fighting over food! The little flies got way more angry than the bigger ones.

A Love Island-esque study showed that high male biased populations led to the evolution of males who lost the ability to maintain higher fertility over successive ejaculations.

Eeek, just another reason for our Love Island males to fear more men being introduced to the island. Some other female responses to receiving sex proteins from across the animal kingdom include - spontaneous ovulation and decreased female sexual receptivity (so a lower sex drive!).

But some results are more relevant to our lives.

In fact, in 2017 Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young won a Nobel prize for their research into the circadian rhythm (our biological clocks). Some of this research was based on our friends, the flies.

Some recent results show that aging in men can affect sperm and sex protein quality leading to significant consequences for fertility.

Usually female age is considered more important in reproductive capabilities, but these findings help researchers look more widely at factors contributing to fertility.

And finally, are there any limitations of Love Island preventing scientific conclusions?

Wondering how the Love Island creators could make the show more scientifically relevant, and possibly more entertaining?

Firstly, the population is far too attractive. Normal populations and sex decisions rely on diverse sexual desirability. In flies, larger females and larger males are preferable as potential mates.

Secondly, the animal kingdom doesn't follow heterosexual monogamy so strictly, allowing trios (or more) and same sex coupling would be more realistic.

Perhaps we'll see that in next year's series.

Niklas Bobrovitz, a PhD candidate in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at the University of Oxford and an honorary fellow at the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, writes about his latest research into the medications that can reduce emergency hospital admissions.

Emergency hospital admissions are rising and, increasingly, policy-makers, clinicians and patients are worried about their effect on cancellations of elective procedures, prolonged waiting times, in-hospital infection rates and costs. However, identifying useful strategies for reducing admissions has proved problematic – interventions designed to reduce hospitalisations often achieve no real-world benefit, yet consume scarce health resources.

One promising intervention that has received little attention is medications; those which help a patient to avoid hospitalisation represent high-value activity in a patient’s overall care. Medications can reduce admission rates by preventing illnesses or mitigating symptoms and exacerbations that would have otherwise required urgent health care.

Our new study in BMC Medicine, therefore, aimed to identify and prioritise medications that have been shown in systematic reviews to prevent patients from requiring emergency hospital care.

What did we do?

We searched for systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials in adults that reported hospital admissions as an outcome. We then assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE criteria. We cross-referenced effective medications with high or moderate-quality evidence with UK, USA and European clinical guidelines to determine which had an acceptable overall balance of benefit to harm.

What did we find?

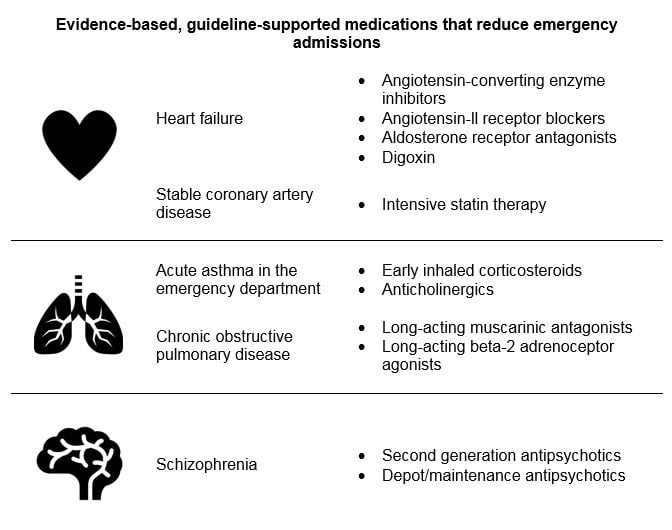

We found 140 systematic reviews, including 1,968 randomised controlled trials and 925,364 patients. We identified 11 medications that significantly reduced emergency hospital admissions, were supported by high or moderate-quality evidence, and were endorsed in clinical guidelines.

Evidence-based, guideline-supported medications that reduce emergency admissions

Evidence-based, guideline-supported medications that reduce emergency admissionsWhat does this mean?

Using the 11 medications that we identified is clinically appropriate and will significantly reduce emergency hospital admissions for patients with heart failure, coronary artery disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and schizophrenia.

In some health systems, these medications are already prescribed as part of routine clinical practice. However, there is evidence of significant variation in their use in the UK, USA and Europe, including under-prescribing and under-dosing. Therefore, policy-makers and clinicians should consider monitoring and improving use of these medications as a strategy to alleviate pressures on secondary acute care.

Existing mechanisms for quality measurement and improvement could be utilised. For example, the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework is a pay-for-performance incentive programme that has reduced prescribing gaps and improved prescribing efficiency. The medications we identified should be considered for inclusion in these types of quality assurance and incentive systems.

Our results may also be used to inform shared decision-making. When communicating treatment options with eligible patients, clinicians could discuss the ability of these medications to reduce the risk of being hospitalised. Given that most patients prefer to stay out of hospitals, we hope that our findings will help to inform their decisions.

This blog first appeared in BMC Medicine.

The study, titled 'Medications that reduce emergency hospital admissions: an overview of systematic reviews and prioritisation of treatments', can be accessed here.

How does £130 in driving fines result in a young man taking his own life?

That question lingers long after the credits roll on the BBC drama ‘Killed by my debt’, which tells the harrowing true story of Jerome Rogers, a 19-year-old courier, who tragically took his own life after debts stemming from two outstanding motoring offences spiralled beyond his control – from £65 each, to more than a thousand pounds within a matter of months.

A combination of unfortunate and all too common circumstances – flexible, insecure employment, working class background, age and unique health factors, prevented him from clearing the debts and ultimately led to his untimely death.

These factors not only made him ripe for exploitation in today’s society, but were also enabled by the very economic structure that now underpins it, the gig-economy. If at this point, you’re thinking, ‘the what?’ you are not alone. ‘Gig-economy’ is a phrase commonly used in society, but little understood by many.

To bring some clarity to the subject, ScienceBlog talks to Dr Alex Wood, a sociologist and researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute, who focuses on the changing nature of employment relations and labour markets, to breakdown everything you need to know about the ‘gig-economy’ and how it could affect you in the future.

What is the gig-economy and how does it work?

The gig-economy is the way in which people are now finding work in non-standard ways. So, instead of working for a traditional employer, they access paid-work through online platforms which enable workers to be hired to do a specific task, or gig. For example, driving jobs like Uber and delivery tasks such as Deliveroo. But also traditional freelance tasks, like website and graphic design.

It’s important to understand that the system of work comes with no frills. Zero-hour contracts and no benefits like holiday pay, sick pay or even a minimum wage.

How has it affected employment?

People are basically working in a much more flexible way. They can be juggling multiple-tasks any given time, and all hours of the day. There is no fixed way of working – the days of the 9-5 are long over for many workers.

On the one hand, this can be a positive set-up if you have control of the work you do, and are able to choose for yourself who you work for, what tasks you perform and when you do them. But to be in this privileged position your skills have to be in high demand, and the reality is that a lot of people are competing for these roles.

When you don’t have this control it can lead to employment instability and insecurity.

People have to work to survive, and if you don’t know where your next hour of work is coming from it can make it impossible to budget and plan for everyday life such as childcare, social life and holidays. Which can lead to people becoming really isolated.

It’s important to understand that the system of 'gig' work comes with no frills. Zero-hour contracts and no benefits like holiday pay, sick pay or even a minimum wage.

How can this instability affect people’s lives?

In these circumstances workers become desperate and feel they have to work whenever an employer wants them to. They relinquish all control which can be incredible stressful, mentally and physically. Control is key.

Often in the press the gig-economy is discussed positively as something mutually beneficial to employers and workers. But in reality it is a trade-off. The reasons why each side wants flexibility are very different.

If the employee is in control, the employer is not, and they are in a position where they have to match labour supply to customer demand. But, for the worker, it is about survival and trying to make a living – as we have seen horrifically reflected in the case of Jerome Rogers.

Who is most at risk?

People competing for less in-demand skilled roles can unfortunately be taken advantage of. Unlike more skilled roles, where there is a much smaller pool of people who can perform them, there are a lot more people that want and can do the job. That means these workers do not have alternative opportunities, so if a client or platform makes unreasonable demands or wants them to work anti-social hours, they have no other choice but to do it. People need to work to survive, so they have to work whenever they are asked to.

We need to rethink our understanding of workers’ rights and employment law. The purpose of the law is to protect people in a vulnerable position, if it is not doing that anymore we need to change the law to make sure that these people are protected.

Most workers who are part of the gig-economy are also not part of a trade union, so they don’t have the protections that come from having a collective voice, which makes them much more vulnerable.

Who has the most to gain?

If workers have skills that are in demand then it can be positive for them, because they can pick and choose who they work for and when. But, in most areas there is a lack of high quality jobs and there are no good quality alternatives available.

For employers however, the benefits are much more obvious. Employing people by task allows a business to reduce labour costs and avoid paying for services that were once expected such as pensions.

Can people make the gig-economy work for them against the odds?

Collective organisation is really important, for example being a part of a trade union.

It is interesting that just last week, Deliveroo workers in London and across Europe went on strike to protest changes to their pay. Even though protections did not exist for these workers when the gig-economy structure launched, they are working collectively to put them in place. Workers who are in a vulnerable position should be able to come together and protect themselves.

Can you tell us a little about your research?

At the moment I am looking at collective organisation and community amongst gig economy workers who are doing remote gig work, in my paper 'workers of the internet unite?'

They operate on similar gig-economy style platforms to Uber and Deliveroo, which perform direct tasks, only these people work remotely from anywhere in the world, supporting digital labour, such as transcription and editing. Even these workers are coming together to create collective organisation.

What can be done to regulate the system and make it fairer?

We need to rethink our understanding of workers’ rights and employment law. The purpose of the law is to protect people in a vulnerable position, if it is not doing that anymore we need to change the law to make sure that these people are protected.

Trade unions should also be able to represent them. Often these platforms claim that workers cannot have a trade union because technically they are a business working for a client, not a direct employee.

There needs to be a recognition that if people are in a dependent situation they are automatically more vulnerable, and should have labour protections. For example, a minimum wage, sick pay and holiday pay. Things that were considered a right in traditional jobs should also be a right in the gig economy.

Dr Wood's paper 'Workers of the internet unite?' is available to view here

- ‹ previous

- 68 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?