Features

Stephen Pates, a researcher from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, has uncovered secrets from the ancient oceans.

With Dr Rudy Lerosey-Aubril from New England University (Australia), he meticulously re-examined fossil material collected over 25 years ago from the mountains of Utah, USA. The research, published in a new study in Nature Communications, reveals further evidence of the great complexity of the oldest animal ecosystems.

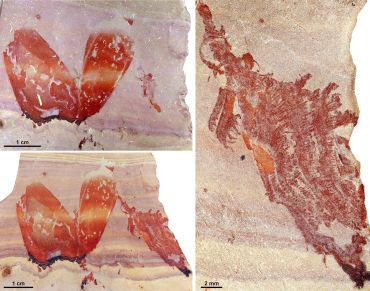

Twenty hours of work with a needle on the specimen while submerged underwater exposed numerous, delicate microscopic hair-like structures known as setae. This revelation of a frontal appendage with fine filtering setae has allowed researchers to confidently identify it as a radiodont – an extinct group of stem arthropods and distant relatives of modern crabs, insects and spiders.

Before and after view of Pahvantia

Before and after view of Pahvantia ‘Our new study describes Pahvantia hastasta, a long-extinct relative of modern arthropods, which fed on microscopic organisms near the ocean’s surface’ says Stephen Pates. ’We discovered that it used a fine mesh to capture much smaller plankton than any other known swimming animal of comparable size from the Cambrian period. This shows that large free-swimming animals helped to kick-start the diversification of life on the sea floor over half a billion years ago.’

Causes of the Cambrian Explosion - the rapid appearance in the fossil record of a diverse animal fauna around 540-500 million years ago - remain hotly debated. Although it probably included a combination of environmental and ecological factors, the establishment of a system to transfer energy from the area of primary production (the surface ocean) to that of highest diversity (the sea floor) played a crucial role.

Even though relatively small for a radiodont (FIG), Pahvantia was 10-1000 times larger than any mesoplanktonic primary consumers, and so would have made the transfer of energy from the surface oceans to the deep sea much more efficient. Primary producers such as unicellular algae are so small that once dead they are recycled locally and do not reach the deep ocean. In contrast large animals such as Pahvantia, which fed on them, produce large faecal pellets and carcasses, which sink rapidly and reached the seafloor, where they become food for bottom-dwelling animals.

Amateur enthusiasts provide research gold-dust

The presence of Pahvantia in the Cambrian of Utah has been known for decades thanks to the efforts of local amateur collectors Bob Harris and the legendary Gunther family.

‘This work also provides an opportunity to celebrate the exceptional contribution of local and amateur collectors to modern palaeontology’ explains Stephen. ‘Without their tireless efforts, knowledge, and generosity, thousands of specimens representing hundreds of new species, would not be known to science.’

Bob Harris is rumoured to have turned down a job offer from the CIA, instead opening up a fossil shop and a number of quarries in the spectacular House Range, Utah. He discovered the first specimens of Pahvantia in the 1970s, and donated them to Richard Robison, a leading expert on Cambrian life from the University of Kansas. The Gunther family are famous for their extensive fossil collecting in Utah and Nevada. Over a dozen species have been named in honour of their contributions to palaeontology, as they have shared thousands of specimens with museums and schools over the years. Among these were specimens of Pahvantia which they uncovered between 1987 and 1997. Donated to the Kansas University Museum of Invertebrate Paleontology (KUMIP), these specimens are described for the first time in our study.

‘I visited the KUMIP in the first year of my PhD,’ says Stephen. ‘It was awesome, exploring such a fantastic collection of fossils from the Cambrian of Utah and Nevada.’

The study has produced the most up-to-date analysis of evolutionary relationships between radiodonts. It shows that filter feeding evolved twice, possibly three times in this group, which otherwise essentially comprised fearsome predators such as Anomalocaris canadensis from the Burgess Shale in Canada.

Pahvantia adds to an ever-growing body of evidence that radiodonts were vital in the structure of Cambrian ecosystems, in this case linking the primary producers of the surface waters to the highly diverse fauna on the sea floor. It also shows the importance of museum collections like the KUMIP, and local collectors, such as Bob Harris and the Gunther family, in uncovering new and exciting findings about early animal life.

The article is available from Nature Communications via this link.

A brand new exhibition launches this Sunday, 9 September (1-5pm) at SJE Arts in Oxford, the concert and arts venue based at St Stephen’s House, one of Oxford University’s Permanent Private Halls.

‘Wartime at an Oxfordshire Monastery’ tells the First World War story of the community of monks once based at the site that the college now occupies, focusing on specific individuals associated with the monastery during wartime. As well as including profiles of members of the monastery itself, the exhibition features a local woodcarver and organist and communities of local nuns, explaining the contributions they made to the First World War, both at home and abroad.

Made possible by a National Lottery heritage grant, the exhibition marks the centenary of the First World War. Around 100 local schoolchildren, volunteers, teachers and academics were involved in the project, which was led by academic and local social historian Dr Annie Skinner, with Dr Serenhedd James.

The former monastery has been described as containing some of Oxford’s most interesting ‘hidden heritage’. Now largely hidden from view behind the modern-day façade of the Cowley Road, the stunning G F Bodley-designed church and monastery was once a key focal point in this area of the city.

The exhibition is one of the ways St Stephen’s House hopes to encourage more people to come and enjoy the site, following the successful development of a concert and arts venue in the college church and cloister, SJE Arts.

When: Sunday 9 September, 1-5pm, SJE Arts

Where: SJE Arts, 109a Iffley Road, Oxford OX4 1EH

Amy Kao, PhD student at the Department of Psychiatry, Oxford University, reveals how she represented the UK at the international ActinSpace hackathon as part of an Oxford team which combined talents to take on a social problem.

Hackathons have a reputation as a software-heavy coding event welcoming only those with specific skill sets and domain knowledge in computer science. However, as diversity continues to emerge as a pivotal aspect of success for any project, the ActinSpace (AIS) hackathon invited anyone from any background to come and work up realistic ideas using space technology in innovative ways.

The experience was truly memorable. In the beginning stages at Harwell, Oxfordshire, within 24 hours my team and I proposed a satellite-based artificial intelligence application to address street harassment. We worked through the night, inspired by the knowledge that we could be building a technology that could truly make the world a better place.

Our proposed platform was a navigation app to guide you the safest way home. In order to find the safest route, the app estimates the danger on each road segment. Crime record databases in the UK and US are public and annotate with exact geo-location. These can be used to count the number of incidents on each road segment. Using convolutions neural networks and satellite data, the app could accurately estimate the number of pedestrians going along each road. This forms the technical basis of our platform. Additional features are AI-driven velocity tracking that can be used to identify whether the user suddenly stops moving, starts running or even deviating from the intended route, all of which are unexpected behaviours on a normal walk home. Using vibration or non-visual cues avoids the need to be constantly looking down at a phone making you appear less lost, and a much less of a viable target.

We pitched our product in seven minutes the following day, and won the hearts of the UK judges. This gave us the unique opportunity to represent the UK at the international semi- finals in Toulouse.

This was an enormous event gathering teams from over 30 countries, all with exciting and novel technologies.

The finals competition in Toulouse brought together people from across the world sharing a passion for technology and innovation. However, it also sadly highlighted the lack of diversity and representation that remains.

Amy Kao and Anna Jungbluth, DPhil students at Oxford

Amy Kao and Anna Jungbluth, DPhil students at Oxford The AIS 2018 had 23% female participation, but only one team among the six finalists had a female team member. There has been considerable movement in increasing this number; however, we see it as our social obligation to do our part and encourage our female peers to take part and pursue activities that they didn’t think they could achieve.

The best part of the team was our diversity, where we were five students from five different countries, coming to Oxford to study five extremely different disciplines (computer science, economics, medicine, physics, psychiatry) ranging from fresh undergraduates to seasoned DPhils. The hackathon really was a problem-solving event, not a software-heavy event at all. It provided the opportunity of working with other astute individuals to propose a holistic solution using space technology and creative business models.

The burst of productivity over one 24-hour period can be extremely refreshing. I would really encourage others to take part, particularly if you’re not in any mainstream programming fields, and even more so if you’re part of an underrepresented demographic (e.g. women in STEM). My bachelor’s was in cell and molecular biology, and my postgraduate research degrees were in pharmaceutical science and neuroscience; perhaps as far removed from space technology as you can get, let alone participating in a hackathon! The mentality of industries are shifting from the limiting idea of entering a career based entirely on what you studied in school to a dynamic stage that embraces diversity and different approaches to solving a problem. Domain knowledge can be quickly accumulated, but the courage to pursue something outside your normal comfort zone and the confidence that you have meaningful contributions requires deliberate time and context to be developed. Just give it a try!

MPLS runs an Enterprising Women lunch and learn in week 4 of each term, welcoming all researchers interested in developing of a supportive network of STEM women. Details are always advertised via eship.ox.ac.uk

Professor Daniela Bortoletto of Oxford University’s Department of Physics explains how a new result from the Large Hadron Collider sheds vital light on the elusive Higgs boson.

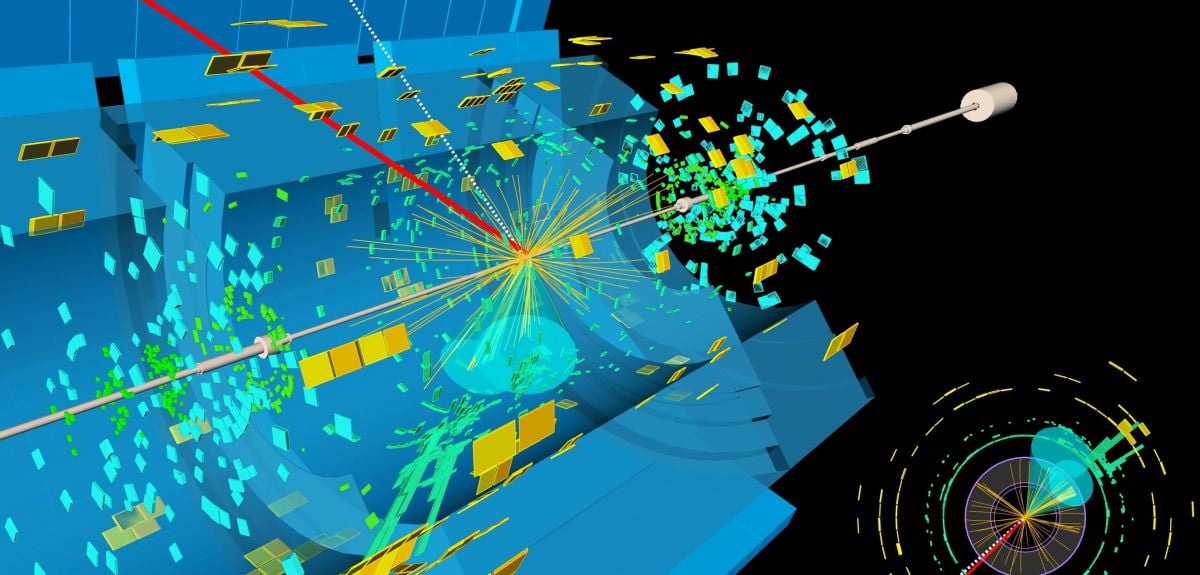

Particle physicists have – at long last – observed the Higgs boson decaying into a pair of bottom (b) quarks at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). This elusive interaction is predicted to make up almost 60% of the Higgs boson decays. Yet it took over seven years to accomplish this observation. This discovery was announced at CERN on August 28 both by ATLAS and CMS.

ATLAS is one of the four major experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. It is a general-purpose particle physics experiment run by an international collaboration and, together with another experiment, CMS, is designed to exploit the full discovery potential and the huge range of physics opportunities that the LHC provides.

The result is a confirmation of the Standard Model. During the early preparations of the LHC, there were doubts on whether this observation could be achieved. Our success is thanks to the excellent performance of the LHC and the ATLAS detector, and the application of highly sophisticated analysis techniques to our large dataset.

UK groups including the Universities of Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool, Queen Mary, Oxford and UCL have made important contributions to this historic achievement.

Finding Higgs boson decaying into a pair of b quarks at the LHC is challenging. Since the LHC collisions produce b-quark pairs in great abundance it is essential to select events where the Higgs boson appears alongside a W or Z particle, which makes the events easier to tag. Our team in Oxford analysed elusive W and Z bosons decays where the decay products of these particles are not directly identified in the detector but are inferred from a large transverse energy imbalance in the event.

Our postdoc researcher, Elisabeth Schopf and my students, Cecilia Tosciri and Luca Ambroz, made significant contributions to the result. Elisabeth played a leading role in optimizing the sophisticated machine learning algorithms that allowed ATLAS to increase the sensitivity to these events. Luca established a new technique that used Monte Carlo events in a clever way and lead to a higher expected significance for the analysis. Cecilia upgraded a method to improve the resolution achieved in the measurements of the decay of the Higgs boson into b-quarks.

This is a very special moment for me personally, and the culmination of an even longer wait. I started looking for the decays of the Higgs boson to b-quarks at the US proton-proton TEVATRON collider with the CDF detector in 2005. Four of my former students completed their theses on searches for the Higgs in events with large transverse missing energy and b-quarks between 2007 and 2012.

The results of this work were used in the final TEVATRON combination which reached about three standard deviations in 2012 - not enough for a discovery. I am delighted that the LHC finally unveiled this important decay mode of the Higgs boson. I did not have any doubt that at the end of this tour de force we will pass the significance of five standard deviations which is necessary to claim a discovery. The LHC is a more powerful accelerator than the TEVATRON and ATLAS is a superb detector.

I believe that this measurement will improve our understanding of the mechanism of mass generation and its possible connections with cosmology and astrophysics.

This is also a new confirmation of the so-called “Yukawa couplings”. Similar to the Higgs mechanism, these couplings to the Higgs field provide mass to charged fermions (quarks and leptons), which are the building blocks of matter. Combined analyses of the Run-1 and Run-2 datasets have resulted in the first measurements of these couplings, as seen in the recent ATLAS observation of Higgs boson production in association with a top-quark pair and the observation of the Higgs boson decaying into pairs of tau leptons.

This result also establishes, for the first time, the production of a Higgs boson in association with a vector boson above five standard deviations. ATLAS has now observed all four main production modes of the Higgs boson. These observations mark a new milestone in the study of the Higgs boson, as ATLAS transitions from observations to precise measurements of its properties.

We now have the opportunity to study the Higgs boson in unprecedented detail and will be able to further challenge the Standard Model.

People admire those who build homes for the poor or donate mosquito nets to those at risk of malaria — but they don’t necessarily want them as friends or romantic partners, finds a new study by researchers at Yale University and the University of Oxford’s Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and Department of Experimental Psychology.

Asked to choose between do-gooders and those who place family members and friends first, subjects said they would rather spend time with those who made people close to them a priority, researchers report in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

‘When helping strangers conflicts with helping family and kin, people prefer those who show favouritism, even if that results in doing less good overall,’ said Yale’s Dr Molly Crockett, assistant professor of psychology and senior author of the study.

The researchers created scenarios designed to test a tough moral dilemma: is it better to help a family member or a larger number of strangers? For instance, they asked whether a grandmother who wins $500 in the lottery should give it to her grandson to fix his car, or to a charity dedicated to combating malaria. In another case, a young woman has to decide whether to spend the day with her lonely mother, or building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

Although participants in the study perceived both choices as equally moral, when it came to looking for a spouse or a friend, they preferred those who helped their grandson or spent the day with mum.

‘Friendship requires favouritism — the key thing about friendship is that you treat your friends in a way you don’t treat other people,’ said Oxford’s Dr Jim Everett, first author of the study. ‘Who would want a friend who wouldn’t help you when you needed it?’

In contrast, this preference was reduced when participants were asked about qualities they wanted in a boss and disappeared when asked about desired traits in a political leader — a social role that requires impartiality.

‘A political leader who represented the interests of themselves or their family over the country would be disastrous,’ said Dr Everett.

According to the researchers, these findings suggest a roadblock for ‘effective altruists’ who argue we should donate money to charity to help relieve poverty and disease in the developing world rather than to a local group that would help fewer people.

- ‹ previous

- 66 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?