Features

Until September BBC Gardeners’ World magazine is running a monthly feature ‘Grow Yourself Healthy’. The May issue focuses on how gardens and gardening can improve sleep, and featured Julie Darbyshire, researcher for the University of Oxford Critical Care Research Group (Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences), alongside other sleep researchers and experts, discussing the benefits of gardening ahead of the RHS flagship flower show in Chelsea.

If you’re not tired, you’re not going to fall asleep. It is perhaps obvious when you think about it, but many of us don’t. We all know we should have 30 minutes of exercise every day but with today’s hectic lifestyle many of us struggle to find the time. Thankfully, for the gym-phobic amongst us with memories of wet and cold cross-country days across the muddy school playing field, exercise needn’t be always about running, or going to the gym. Ever tried digging over a flower bed or veg plot? Gardening can be a great way to achieve an all-body workout. It can also be a low-impact path to being a little bit more active. Some gentle pottering in the garden (beneficial in itself) can lead to other tasks, which leads to more physical exertion, which can only ever be a good thing... But physical exercise is not the only way that gardening can help you sleep at night.

Sleep is hugely influenced by your natural circadian rhythm. Every cell in the human body has a clock that’s controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain. The SCN is linked directly to the eyes. Light then, is a key driver to circadian control. Research has demonstrated if you put people into dark places with no external clues to the time of day, their circadian rhythms will become abnormal very quickly. The body needs appropriate exposure to daylight to regulate the body’s responses to help ‘reset’ this clock and keep you “on time”. Many of us spend the majority of the day inside. Light levels in an office, even close to a window, will be far below those of bright natural daylight which is around 20,000 lux. The spectrum of light inside is also quite different. Natural daylight is quite ‘blue’ (5000-6500K) and the body expects a change to more orange/red tones as the day fades to night. This is one of the reasons why ‘screen time’ in the evening isn’t good when you are supposed to be preparing for sleep. The light entering the eyes is too blue for the time of day. Spending the majority of the day inside where light levels are both low (lux levels around 150 are not uncommon) and often in the ‘warmer’ spectrum range (<3000K) is biologically confusing. Getting outside, getting a bit out of breath, and even being a bit chilly, are the best ways to regulate your body clock.

The Critical Care Research Group at the University of Oxford has been exploring how the hospital environment influences the patients’ experiences of their admission. As part of a research project (SILENCE) that was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (Research for Patient Benefit, ref: PB-PG-0613-31034), the group has been studying sleep patterns in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The results of the SILENCE sleep study have been published in the Journal of the Intensive Care Society. Julie Darbyshire, lead researcher on the project, was also interviewed about the study for a critical care focused podcast series.

The research team used several different ways to electronically measure sleep and also asked patients and their nurses who were looking after them overnight to complete a questionnaire. All methods of sleep measurement confirmed that sleep was poor. Most patients were able to sleep for at least some of the time but the average total sleep overnight was just over two hours. This is a long way short of the seven to eight hours sleep that is recommended for most adults. The team also found that the average time a patient in the ICU can expect to be asleep before awakening is just one minute. This can leave patients exhausted by the end of the night and many feel that they haven’t slept at all.

Professor Duncan Young, senior clinical lead for the Critical Care Research Group and honorary NHS consultant in anaesthetics and intensive care medicine, said: ‘Patients clearly struggle to sleep well when in intensive care. Sleep deprivation likely leads to confusion, and confusion is thought to complicate the healing process and slow recovery. The real challenge is knowing what to do to improve things for patients.’

Julie says: ‘Patients may be offered earplugs and eye masks to help them sleep, but not everyone likes wearing them. Improving the environment has to be the better approach. This should include reducing sound levels, making sure that patients have access to plenty of natural light during the day, and turning lights off overnight.'

Julie also suggests that having access to the outside is likely to benefit patients recovering from their critical illness. Early hospital environment work by Robert Ulrich in the 1980s showed that patients who could see trees outside went home sooner and experienced lower levels of pain than those patients who could only see a wall. More recent studies suggest that access to a garden during a hospital stay can lower stress levels in both patients and their families. Recognising this, Horatio’s Garden is a charity that creates and builds accessible gardens for NHS spinal injury units and a number of hospitals around the UK have gardens where they can take their ICU patients during the day.

The team in Oxford has been able to show how different sleep in the ICU is when compared to normal healthy adult sleep patterns. As well as being awake for much of the night, patients in the ICU experience almost no rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, or deeper, restful sleep. This means that even when patients do sleep in the intensive care unit, their sleep is poor quality. Healthy sleep would include about 20% of REM sleep and about 20% of deep sleep. Good quality sleep is vital for preservation of the immune function, recovery, and can help prevent delirium which is a common problem for patients in the intensive care unit. Persistent poor sleep may also lead to longer-term cognitive and mental health problems. It has recently been reported that patients struggling to cope mentally after their critical illness can also experience worsening physical health .

Gardening is, in and of itself, a positive, forward-looking activity. After all, no-one plants carrot seeds without expecting to eat carrots in the future! The Kings Fund report on Gardens and Health (2016) highlights some of the mental health benefits to just being in a natural environment, GPs in Scotland are working with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to offer ‘nature prescriptions’ in Shetland, and the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has teamed up with GPs across the UK as part of a new ‘social prescribing’ scheme. The University of Oxford Gardens, Libraries and Museums (GLAM) project for well-being is looking at this in more detail. Researchers from the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences) are working with GLAM to promote knowledge exchange, raise awareness, and to add to the evidence base to support wider implementation of social prescribing.

This year’s Chelsea Flower Show has a strong focus on the health benefits of interacting with nature. Many of the show gardens feature gardening for resilience, recovery, and wellbeing. So if you’re struggling to sleep at night, go outside during the day, plant some seeds, prune something, dig the borders, enjoy the fresh air and the sunshine, and reap the rewards of a good night’s sleep.

For Mental Health Awareness Week 2019, we are exploring how the University of Oxford has been researching the potential of online psychological treatments to support better mental health care.

The effects of the internet revolution over the past decade alone has been astounding. From the palm of our hand, the top of our desks and in our pockets, we have drastically altered the way we conduct our everyday lives and enhanced our capabilities.

The scale of internet use alone is evidence enough of its effects. According to the Office for National Statistics, 90% of adults in the UK reported being regular internet users and virtually all adults aged 16 to 34 reported being recent internet users (99% in 2018 compared to 44% of adults aged over 75).

Internet driven technologies have enhanced most aspects of our everyday existence, but what’s the potential for harnessing this capability for better health and care? We are seeing both national and local policies that are emphasising the need for embracing a spectrum of internet driven technologies to support professionals and patients alike.

But what about mental health? This Mental Health Awareness Week, the scale of the mental health challenge is serving as an urgent reminder as to why we should be embracing innovation in tackling it.

One in four of us at some point will face a mental health problem each year. 300,000 people leave the work place each year because of mental health issues and it accounts for 15.4 million sick days.

It presents one of the most burning social and economic issues facing the world today.

Some of the most common disorders seen by mental health professionals are Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). SAD normally starts in childhood or adolescence and is one of the most persistent disorders when not treated. PTSD is a common problem that can occur after a traumatic event and can lead to chronic disability and high healthcare costs if left untreated.

Both of these conditions normally respond well to psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT). Specific CBT interventions for these problems were developed by researchers at the University of Oxford at the Oxford Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma (OxCADAT). These treatments are now widely used within the NHS and beyond, and are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

While CBT can effectively treat these two common conditions, like any medical intervention, it comes with its own unique set of challenges. Common across mental health services, patients can face difficulties in accessing treatment given the high demand and limited number of therapists.

In the light of these problems and the scale of internet use, one potential solution that is receiving attention here at the University of Oxford is the use of internet-based versions of effective psychological therapies that have traditionally been delivered face-to-face.

OxCADAT have been investigating therapist-guided, internet-based forms of their previously developed CBT programmes for SAD and PTSD and assessing their effectiveness and potential.

The early research has shown some promising results.

The clinical outcomes of these early studies have suggested that internet-delivered CBT may be just as effective as face-to-face therapy sessions. Crucially, good outcomes have been achieved with a drastically reduced workload for the therapists compared to face-to-face clinical settings: 20% for SAD and 25% for PTSD treatment.

As well as being less resource intensive, the early results have indicated that patients may find online-delivered therapies just as acceptable as traditional face-to-face therapies. The early pilots have shown that patients reported greater control over their treatment and greater convenience when undertaking therapy online. In patients suffering with common mental health disorders, this has the potential to attract a greater number of people seeking treatment.

Therapy for common mental health disorders going online has the potential to transform and improve the mental health treatment offering. There could be reduced waiting lists, greater successful turnover of patients, more patients being able to access treatment even if they cannot attend face-to-face therapy and a reduction in the societal and economic burden of mental health problems.

What the key focus is now here at Oxford is examining these treatments further and building the evidence base. Oxford has been a world leader in the development of face-to-face psychological therapies, which are now mainstream throughout the NHS. It is hoped that online CBT can reach the same level of success.

Furthermore, there is also ongoing research adapting internet therapies for global use. Online solutions to these conditions could make a big difference to the global mental health crisis, if we can find effective methods to transport and adapt these programmes for use around the world.

Although these are early days, the results are indeed encouraging. If further research is just as promising, Oxford would be building on its proud legacy in leading some of the greatest evolutions in mental health treatment.

In a series of videos launching The Mathematical Observer, a new YouTube channel showcasing the research performed in the Oxford Mathematics Observatory, Oxford Mathematician Michael Gomez (in collaboration with Derek Moulton and Dominic Vella) investigates the science behind the jumping popper toy.

Snap-through buckling is a type of instability in which an elastic object rapidly jumps from one state to another. Such instabilities are familiar from everyday life: you have probably been soaked by an umbrella flipping upwards in high winds, while snap-through is harnessed to generate fast motions in applications ranging from soft robotics to artificial heart valves. In biology, snap-through has long been exploited to convert energy stored slowly into explosive movements: both the leaf of the Venus flytrap and the beak of the hummingbird snap-through to catch prey unawares.

Despite the ubiquity of snap-through in nature and engineering, how fast snap-through occurs (i.e. its dynamics) is generally not well understood, with many instances reported of delay phenomena in which snap-through occurs extremely slowly. A striking example is a children’s ‘jumping popper’ toy, which resembles a rubber spherical cap that can be turned inside-out. The inside-out shape remains stable while the cap is held at its edges, but leaving the popper on a surface causes it to snap back to its natural shape and leap upwards. The snap back is not immediate: a time delay is observed during which the popper moves very slowly before rapidly accelerating.

The delay can be several tens of seconds in duration — much slower than the millisecond or so that would be expected for an elastic instability. Playing around further reveals other unusual features: holding the popper toy for longer before placing it down generally causes a slower snap-back, and the amount of delay is highly unpredictable, varying greatly with each attempt.

See more videos: Episode two: how fast the popper toy snaps, and how its unpredictable nature can arise purely from the mathematical structure of the snap-through transition.

Professor Katrin Kohl of Oxford's Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages has written a letter to The Guardian calling on Ofqual to 'urgently adjust grade boundaries and implement proper quality control for Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) exams'. The letter has been signed by 150 university teachers, and The Guardian has also published a report on the issues raised. Here, Katrin Kohl gives further details about how the design and grading of exams are affecting MFL subjects and the pupils studying them.

Languages have long been considered ‘difficult’. The reasons are obvious – you can’t make progress without learning lots of vocabulary, you have to get your mind round illogical grammar rules and avoid getting discouraged by mistakes when applying them, and you project yourself publicly as an ignoramus every time you open your mouth to practise speaking. Moreover, words and rules are almost as quickly forgotten as they’re learned. Add to this the fact that English native speakers already know the most useful language in the world including the language of the internet and dominant pop culture, and it’s hardly surprising that foreign language learning in the UK is suffering.

There are many joys and rewards in learning languages, too – cognitive benefits, cultural enrichment, communicative empowerment, sense of adventure, creation of a new identity. Yet these require careful nurturing, patience and time. And time is in particularly short supply in crowded school timetables.

Powerful measures are needed if the difficulties are not to win the day. The most effective one is making the subject compulsory at school. In other European countries that’s normal. In England, that battle was lost in 2004 when the Labour government made languages optional at GCSE. Further nails were hammered into the languages coffin with the intensive promotion of STEM subjects as a career advantage, the abolition of the fourth AS subject from 2016, and the push towards fewer GCSEs with the reformed qualifications. Counter-measures by the government such as the EBacc and compulsory language teaching at primary level have not succeeded in reversing the trend.

There’s now widespread alarm at the rapid loss of language skills as schools reduce provision and universities close language departments. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Modern Languages has demanded a Recovery Programme; the British Academy has issued a Call for Action together with the Royal Society, Academy of Medical Sciences and Royal Academy of Engineering; and the Arts and Humanities Research Council has invested some £16 million in research programmes designed to give languages a shot in the arm.

Meanwhile the spotlight is on the GCSE and A level exams in Modern Foreign Languages – are they fit for purpose? This is all the more critical in a context where other factors are impacting negatively on the subject. Yet schools report that it’s primarily the difficulty of the course and exams that is prompting learners to drop the subject. There are two interconnected issues here. One is ‘severe grading’. The other is the intrinsic difficulty of the exam papers, which in turn generates courses that are too demanding and makes for stressed teachers and learners. The exam regulator Ofqual is ultimately responsible for both issues since it oversees the work of the exam boards and maintains standards across subjects.

After some ten years of complaints from teachers, five years of support from the higher education subject community, and several consultations and research studies, Ofqual acknowledged last November that grading in MFL A levels is indeed, as teachers had claimed, ‘severe’ and that French, German and Spanish A levels are ‘of above average difficulty’. Yet Ofqual decided not to make an adjustment to the grades.

A consultation is now underway for a similar exercise with GCSEs in MFL. The decision expected in the autumn. So what about the impact of severe grading? Ofqual has been amassing statistical proof to show that there is no causal link with falling numbers. But can that possibly be the case? Which learner, parent or school will go for a subject that has statistically been proven even by the exam regulator to be ‘severely graded’ and thereby put the student’s university place at risk?

A key factor underlying excessive difficulty of the language exams for English learners is the presence of native and near-native speakers of the language in the exam cohort. This factor is unique to Modern Foreign Languages and it was partially addressed by Ofqual in 2017 with a small one-off adjustment to A level grading in French, German and Spanish. But what hasn’t yet been acknowledged is their effect on the exam papers.

This is significant, especially for smaller languages where the proportion of native speakers tends to be highest. Research commissioned by Ofqual showed that in the German A level sample, almost half the students gaining an A* were native-speakers, while at grade A, they made up almost a fourth. These are invisible to examiners, exam boards and Ofqual when it comes to scrutinising marks profiles. So even if the exam is far too difficult for non-native speakers, there will be enough marks gained at the top end to suggest the exam is working.

In fact an examiners’ report for the 2018 A level in German indicates that there may be insufficient awareness of difficulty as an issue. In the case of a reading comprehension question concerning a grammatically highly complex sentence with a word very unlikely to be familiar to an English learner, the examiner comments that the question ‘discriminated well. A few candidates answered this correctly and gained a mark’. The sample answer given in the report for this part of the exam is likely to be by a near-native speaker.

Learners, then, face a triple whammy – a rushed, stressful course that can’t possibly prepare them thoroughly for the exam at the end of it; a demoralising exam experience that makes them feel failures; and a grade that is below what they would get in another subject for equivalent performance.

So what’s to be done? There’s a window between now and Ofqual’s autumn decision for a change of direction. Ofqual needs to acknowledge the overwhelming evidence of anomalies in Modern Foreign Languages assessment – and act:

- Reopen the question of A level grading, and carry out the necessary adjustment to eliminate ‘severe grading’.

- Simplify the exam papers, and ensure that the exam boards start working with robust criteria for controlling the level of linguistic difficulty appropriately for non-native speakers.

- Gain better understanding of the impact of native and near-native speakers on exam papers, marking and grading, and make the necessary adjustments for all languages so non-native speakers are rewarded appropriately.

The subject community in schools and universities is keen to support this endeavour. If Ofqual does not address these matters now, language learning in the UK will face an inexorable further downward spiral caused by unrealistic expectations, exam difficulty, severe grading, irreversible loss of provision in schools and universities, and an intensifying teacher shortage.

You can read Ofqual’s response to the Guardian article and letter here.

Read Professor Kohl's letter to Ofqual, plus supporting documents on the Creative Multilingualism website.

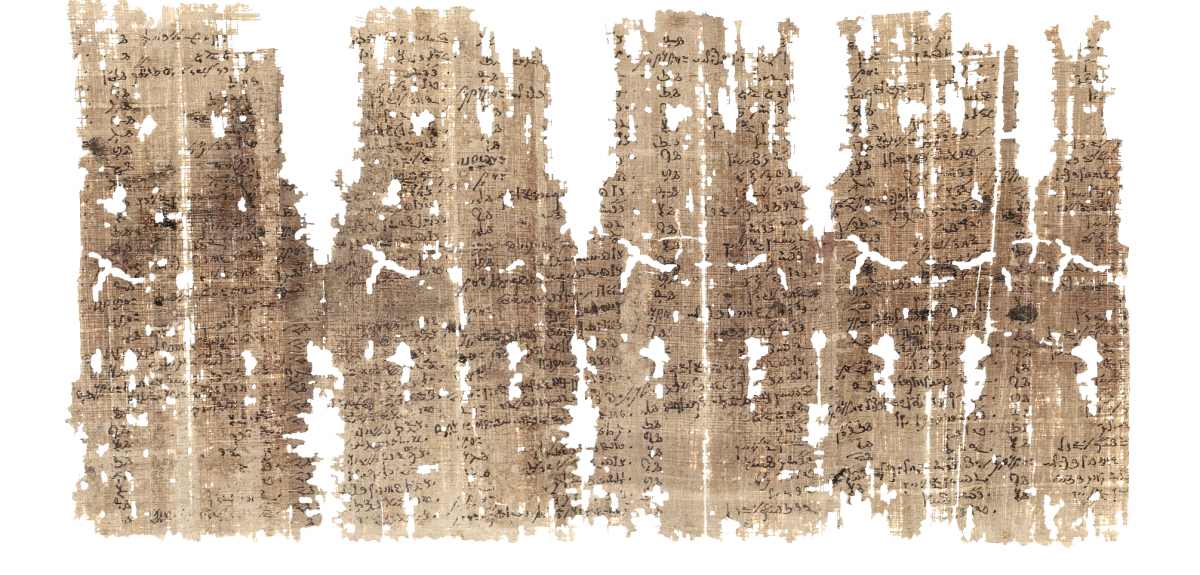

This article was produced by the University of Würzburg and appears in its original form here. Researcher Dr Maren Schentuleit is incoming Associate Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford.

Imagine archaeologists working 2,000 years from now to decipher the account statements of a large commercial enterprise that ended up in the bin in 2018 and have been forgotten since. The majority of these notes are in a deplorable condition: eaten by mice, glued together, torn and fragmentary, and written in a strange script that cannot be found in any other place. What makes the work even more difficult is that the individual scraps of paper are not neatly collected in one place, but are distributed across many museums and libraries in Europe. Which is why, for example, no one has yet noticed that the upper half of a rather unfortunate note is in Vienna, while the lower half is in Berlin.

We must confess: The comparison with today's account statements isn’t quite correct. Nevertheless, it provides a good picture of the work that Egyptologists from the Julius-Maximilians-University of Würzburg (JMU) and their colleagues from Bordeaux will be doing in the coming years. DimeData: This is the name of the research project that the French Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) have now approved. The two institutions will provide around €450,000 over the next three years, a good half of which will go to the JMU. The project leader there is Professor Martin Andreas Stadler, holder of the Chair of Egyptology, and Lecturer Dr Maren Schentuleit, research assistant to the Chair, will be responsible for the concrete work.

The aim of the project is to investigate the Egyptian temple economy from sources that are "rich in content, difficult, fragile at first glance, but then uniquely rich in detail," as Stadler says. At the same time, they will being publication of an online platform with the edition of around 40 representative texts. Under the keyword "Digital Humanities", ancient historians and Egyptologists will be provided with new sources that will put the knowledge about the economic life of Egyptian temples in the Roman Empire on a new footing. In fact, the researchers involved assume that the results of their investigations will force researchers to revise their understanding of the situation during this period.

"In this project we are concentrating on lists of accounts from the economic management of the temple of Dimê, which originated around the time from 30 BCE to the second century CE," explains Stadler. At that time Rome had taken power in Egypt. While older research blamed the Romans for the decline of the temples in Egypt, today it is believed that Rome even provided economic stimulation in Egypt. This controversy is one of the motivations of the research project that has now been launched.

Southwest of Cairo, in the middle of the desert, near the oasis Fayum, lie the remains of the temple Dimê. The temple was dedicated to Soknopaios, who was often depicted with a crocodile’s body and a falcon’s head. Around the middle of the third century BCE the place was abandoned and never populated again, which proved to be a stroke of luck. In the dry desert, ancient documents on papyrus remained well preserved until they were accidentally rediscovered at the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, the text fragments were then sold without treatment by archaeologists and mixed with other finds; today they are scattered in museums and collections in Vienna and Berlin, London and Paris, as well as many other places.

These papyri can be up to two and a half metres long. Narrowly described in long columns, the editions of the temple treasury are recorded over many years in such papyri. "There, for example, people are listed who were paid by the temple," explains Maren Schentuleit. These are priests or scribes on the one hand, but also state officials and inspectors on the other. From such sources, a good picture of the contacts between Egyptian temples and Roman administration can be gained.

Wheat, bread, olive oil, olives – salted or marinated in water: The temple's expenses for everyday goods are also meticulously noted on the papyri and provide information about consumer habits in Egypt around 2,000 years ago. Ideally, they enable researchers to draw conclusions about price trends over centuries, and thus also about economic change during this period. Wool, beer, wine– the latter even in different qualities: The menu of antiquity hardly seems to differ from a modern one.

Philology is not simply a matter of “read and translate,” however, especially with the papyri from Dimê, because those fragments are written in demotic writing. "This was a handwriting used especially for everyday use. It originally derived from hieroglyphic writing, and emerges around 650 BCE," says Stadler. The deciphering of this writing is a challenge even for experts, especially because the writers in Dimê had also developed their own writing style. As if that weren't enough difficulties, there is also the fact that many of the ancient documents are full of holes, torn, and fragmentary, with parts of one and the same fragment kept in different collections without anyone knowing.

"Anyone who specialises in demotic texts must enjoy deciphering, and be patient, persistent, and be able to tolerate frustration (at every turn)," says Maren Schentuleit. Translating an entire column in one day already counts as a great success, remarks the Egyptologist. Of course, after years of working with this script, she has a rich set of skills at her disposal to help her decipher it. In demotic writing, for example, there is always a descriptive element at the end of the word that indicates whether it is a plant, a mineral or a type of material – helping to narrow down the search for solutions.

When trying to decipher completely unknown words, Schentuleit looks for a connection with words in the older Egyptian or later Coptic language, hoping that similarities will help her. Or, she remembers having already seen the same combination of signs in another text and can draw conclusions about the meaning in a new context. For this reason, too, the Egyptologist can come to appreciate researching accounting lists - a text genre that otherwise promises little reading pleasure. "They contain many repetitive elements and thus enable comparisons to be made across many text fragments."

The aim is, within three years, to edit 40 texts and produce an online database. "We are doing important preliminary work for younger scholars and laying the foundation for further research projects," explains Stadler. And, of course, the results will help to significantly improve our understanding of temples as economic centres in Egypt, their relationships with other temples, intellectual exchange within the country - and, ideally, the controversy over the influence of the Romans on these Egyptian institutions.

- ‹ previous

- 55 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths? How do we measure success in the fight to save nature?

How do we measure success in the fight to save nature?