Features

Heart strings

Heart stringsIf you thought 'tugging at your heartstrings' was just an expression, think again.

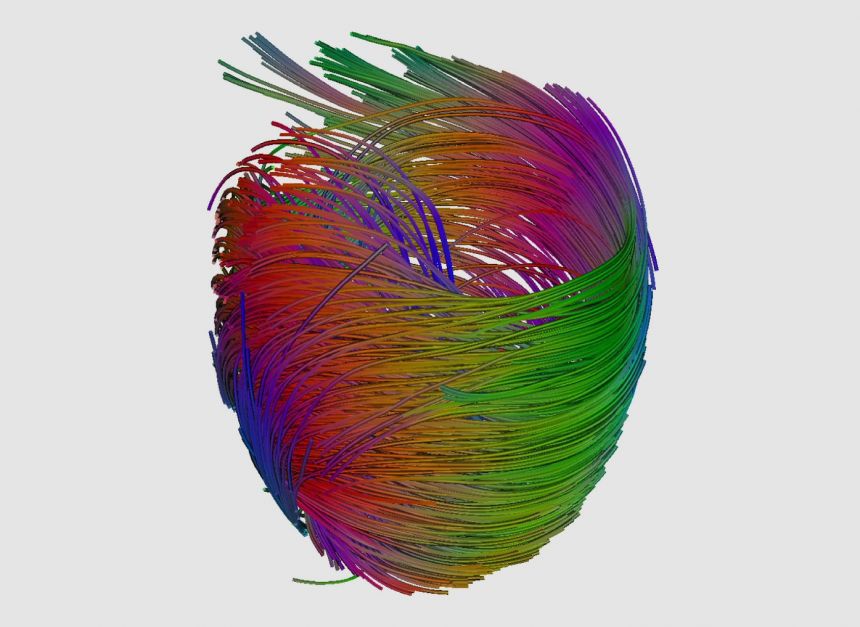

In a tale appropriate to the cardiac-thumping run up to Valentine's Day an Oxford University researcher has produced an image showing the orientation of 'strings', or more scientifically-speaking 'muscle fibres', within the human heart.

The image above by Patrick Hales, from Oxford University's Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics [WTCHG], won the runner up prize in the British Heart Foundation's Reflections of Research competition.

It was generated from an MRI scan of a heart, using Diffusion Tensor Imaging. The scan tracks the movement of water molecules throughout the heart muscle, which reveals how the muscle cells are aligned. The lines represent the orientation of muscle fibres in the heart’s biggest chamber, the left ventricle.

'This technology allows us to model the structure of muscles in the heart in a non-invasive way, and how diseases can cause it to change,' Patrick told us.

'In the future, we hope that our research might be able to determine how the structure of the heart is damaged during a heart attack, and how the muscle fibres respond.'

'We also hope that our computer models of individual hearts will one day be used as a tool for diagnosis, and could even provide patient-specific assessment of treatment options. Imagine your doctor trying out treatments on a ‘virtual’ version of you, before choosing the right prescription.'

The image was produced as part of a collaborative research project between researchers at medical, basic science, and computing departments at Oxford University, funded jointly by the BHF and the BBSRC.

Also deserving a special mention is the image 'The tree of life' (below) by Patrizia Camelliti of Oxford's DPAG that made the competition's shortlist.

It shows the orientation of cells deep within the heart, visualised using multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. The cells have been stained with special pigment molecules which absorb the light from a laser and emit light of a different wavelength.

According to Patrizia: 'The muscle cells of the heart intertwine like the branches of a great banyan tree. This intricate structure is essential for generating force to pump blood around the body.'

'My research aims to reveal the complex structural and functional alterations affecting the heart during heart failure, and how people with this condition can be helped by implanted devices that help the heart to pump.'

'The results will help engineers improve the design of these devices, with direct benefits for the thousands of people awaiting a heart transplant.'

Could the carbon dioxide belched out by heavy industry be put to good use?

It's a question a number of researchers are looking into including Dermot O'Hare and Andrew Ashley of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry.

They have developed a new process for capturing and storing CO2 and converting it into the useful chemical and fuel methanol. A report of their research is published in the journal Angewandte Chemie, and they are now working with Oxford University Innovation to exploit their idea.

Dermot told The Engineer that 'CO2 is a hard nut to crack because its bonds are very strong,' but that 'methanol is quite a nice fundamental building block for organic chemistry.'

He goes on to point out that right now most of the methane we use comes from fossil fuel reserves and that their technique would be win-win in that it would both sequester CO2 and produce a useful chemical and possible alternative fuel source for vehicles, devices or power plants.

The process works by harnessing the power of highly reactive chemical mixtures called Frustrated Lewis Pairs (FLPs).

FLPs are able to rip apart hydrogen molecules and bond with the hydrogen ions. But after this reaction the Oxford team worked out that the Pairs would still be 'frustrated' and reactive enough to bond with CO2. They've now shown that their approach can exclusively produce methanol from CO2 at low temperature and pressure (160 °C at standard pressure).

'Current technology is not selective for methanol and therefore not carbon efficient,' Dermot told us. 'Side products of other carbon capture technologies such as carbon monoxide and methane can also be just as undesirable as CO2.'

As well as not producing these unwanted byproducts the new process doesn’t require expensive and toxic transition metal catalysts and is not poisoned by carbon monoxide - a gas often created during incomplete combustion.

The Oxford team are currently looking to make the process suitable for industry and Isis Innovation has patented the technology and is working with the inventors on a strategy for commercial development.

For more contact Jamie Ferguson: [email protected]

Read more in The Engineer and New Scientist

Today's Times carries a letter from scientists working on the Cassini mission.

Cassini, you may remember, is one of the projects that STFC has chosen to withdraw from as part of a cost-cutting exercise. It's also a project that Oxford scientists have made a major contribution to.

Simon Calcutt, from Oxford University's Department of Physics, is one of the letter's signatories who write: 'the UK Cassini teams that discovered the ice volcanoes on the Saturnian moon Enceladus, the rich chemistry of the prebiotic atmosphere of Titan, and the mechanism of Saturn’s auroras now face imminent disbandment, abandoning still-functioning UK-led instruments in orbit around the planet.'

Unless other funding sources can be found the decision signals a sad end to what has been a major UK science success story. Both Mark Henderson in The Times and Jonathan Amos on BBC Online mull over the consequences and how it might impact on UK involvement in future missions and the next generation of British space scientists.

Whatever you think about how spending on space science should be prioritised it's worth noting just what a phenomenal success Cassini has been so far, even just from the Oxford perspective:

Back in January 2004 Oxford University scientists working on data from Cassini identified a jet stream in Jupiter's atmosphere that resembles similar weather features found on Earth.

They were part of the team behind the Infrared Spectrometer that, in July 2004, was sent to scrutinise Saturn, its rings and moons, as the spacecraft hurtled by the giant planet.

Years of data crunching and modelling saw them make a series of major discoveries, highlights include:

Finding a hexagon-shaped 'hot spot' in the middle of Saturn's chilly north pole: the result of air moving towards the pole, being compressed and heated up as it descends over the poles into the depths of Saturn. Reported in Science, this gave clues to the atmospheric formations found on Jupiter, Neptune and Mars.

New observations of Saturn showed that its southern polar vortex is similar to hurricanes found on Earth. Both have cyclonic circulation, a warm central 'eye' region surrounded by a ring of high clouds - the eye wall - and convective clouds outside the eye. These 'saturnicanes' also resembled polar vortices on Venus, giving further weight to the idea that understanding the weather on one planet call tell us a lot about weather on others (including our own).

Only last year, Oxford scientists using Cassini reported in Nature that they had come up with a new way of detecting how fast large gaseous planets are rotating: a method which suggests Saturn’s day lasts 10 hours, 34 minutes and 13 seconds – over five minutes shorter than previous estimates based on the planet’s magnetic fields.

These are just a few examples and, according to NASA, in Cassini's new extended mission there should be many more exciting discoveries to come:

'The extension presents a unique opportunity to follow seasonal changes of an outer planet system all the way from its winter to its summer... The mission extension also will allow scientists to continue observations of Saturn's rings and the magnetic bubble around the planet known as the magnetosphere. The spacecraft will make repeated dives between Saturn and its rings to obtain in depth knowledge of the gas giant. During these dives, the spacecraft will study the internal structure of Saturn, its magnetic fluctuations and ring mass.'

It's a shame that it looks like researchers from Oxford and around the UK will only be able to cheer the plucky old probe on from the sidelines instead of being at the heart of a truly unique space odyssey.

They built telescopes and transparent beehives, observed the microscopic world of cells and the motions of the planets, developed new methods of calculation and invented everything from watches to talking statues.

They were a small group of mid-17th Century natural philosophers based at Oxford University who would play a key role in both the scientific revolution and the founding of the Royal Society - which this year celebrates its 350th birthday.

This group emerged at one of the most turbulent times in English history, when the horrors of civil war were swiftly followed by the turmoil of first the Commonwealth, then the Restoration.

At Oxford, academics were regularly ejected from their posts for their political views and replacements were sent to reform the University to match the current government’s agenda. But these political purges were incomplete and incompetent affairs that, by accident, turned Oxford into a melting pot of different opinions, ideas and personalities.

Wilkins, Wren, & Wadham

One of the most influential of these personalities was John Wilkins, Warden of Wadham College from 1648-1659. Wilkins was sent to Oxford by parliament to help eliminate its royalist leanings but he turned out to be a tolerant, charming man less interested in politics than in new scientific ideas and inventions.

Wilkins turned Wadham into a haven for ‘experimental philosophy’, setting up a club there that would attract some of the great minds of the age: members from Oxford University included Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren, Seth Ward, Robert Wood, and John Wallis. He created Wadham’s formal gardens where members tested out clockwork flying machines, seed drills and beehives (Wren's design was particularly innovative), and installed both scientific instruments and amusements, such as a statue that ‘talked’ via a tube that threw his voice.

It’s striking just how modern Wilkins’s approach seems today, as he brought together those studying different disciplines and encouraged them to work collaboratively: forging friendships, intellectual connections, and a spirit of enquiry that would animate the newly-formed Royal Society in 1660 and endure for decades to come.

The most famous experimentalists to join Wilkins’s circle were undoubtedly Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke.

Wren’s later career as an architect has come to overshadow his achievements as a scientist and engineer: perhaps it doesn’t fit posterity’s image of the bewigged 17th Century gent that Wren was as at home inventing new musical instruments, dissecting fish, or creating machines for recording microscope images as he was designing Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre.

Joining Wadham as an undergraduate in 1650, Wren would become friends with Wilkins and, later, Hooke. Wren’s main interest, to begin with, was mathematics but he was soon caught up in Wilkins’s enthusiasm for astronomy, building an 80-foot telescope with him so that they could observe the Moon.

After a fellowship at All Souls College, Wren would hold the position of Savilian professor of astronomy (1661-1673) during this time contributing to the early Royal Society meetings on topics as varied as optical lenses, friction brakes and insect physiology. In due course he would serve as Vice-President, and then the fourth President of the Royal Society.

‘England’s Leonardo’

Robert Hooke, dubbed ‘England's Leonardo’ by Oxford’s Allan Chapman, had an unparalleled gift for creating and perfecting mechanical devices.

He demonstrated this aptitude as a chorister at Christ Church, assisting first Thomas Willis and then Robert Boyle with their chemistry apparatus and experiments - he was responsible for Boyle’s first working vacuum pump.

Hooke fed off the problems and ideas of other members of the Wadham club: creating a clockwork machine to help Seth Ward record astronomical observations, also measuring the weight of air, and inventing a spring-regulated watch. He would go on to be curator of experiments at, and a secretary of, the Royal Society, performing numerous scientific investigations, coining the biological term ‘cell’, and, in publishing his masterwork Micrographia - on the natural world seen through a microscope - founding a new scientific discipline.

So what was it about 1600s Oxford that attracted so many early scientists?

Part of the attraction, according to Cambridge historian Simon Schaffer, was the infrastructure: Oxford offered a profusion of printers and stationers who could help budding scientists publicise their work - at a time when publications were becoming an essential part of both disseminating and learning the new knowledge about the natural world.

Oxford was also a good place to acquire machines no self-respecting natural philosopher could be without - such as measuring instruments, sundials and telescopes - due to both the work of local artisans and its proximity to London’s workshops.

The city also boasted some of the oldest coffee shops in Britain: places where those interested in science would meet, indulge in caffeine-fuelled debates, and even sometimes perform ad hoc experiments.

Planets & ciphers

Wren and Hooke may be the most famous members of the Oxford circle but it included other extremely influential figures: notably John Wallis and Seth Ward.

Wallis was appointed Savillian professor of geometry in 1649, and incorporated MA from Exeter College, whilst Ward arrived as Savillian professor of astronomy in 1650 and was a fellow-commoner at Wadham.

In over 50 years at Oxford Wallis established a reputation as one of the world’s leading mathematicians. In a series of seminal publications he introduced the sign for infinity and developed methods for dealing with indivisible or infinitesimal quantities - work that would have a profound influence on Newton’s contribution to calculus. He also wrote a history of algebra in which he stressed the achievements of Newton and English mathematicians over their continental rivals.

Wallis was a renowned cryptographer and was also intimately involved with the founding and early meetings of the Royal Society: contributing over 60 papers to Philosophical Transactions.

Ward’s career was almost as stellar - he produced a study on comets and influential works on the paths of the planets as well as a simplified version of Kepler’s second law of planetary motion. He then collaborated with Wilkins to defend the merits of a scientific education for clergymen, and investigated the development of a ‘universal language’ to communicate philosophical ideas.

Ward’s flair for organisation cut short his scientific career - he became President of Trinity College in 1659, and later an ecclesiastical administrator as Bishop of Exeter, then Salisbury - actively participating in early meetings of the Royal Society but then gradually leaving his scientific studies behind.

Influence & legacy

Alongside Wallis and Ward we could have highlighted the mathematician, economic thinker and advocate of decimalisation Robert Wood, as well as non-University members such as the chemist Robert Boyle.

But what does this whistle-stop tour really tell us about Oxford’s contribution to 17th Century science and the Royal Society?

As Simon Schaffer points out, the Oxford circle was one of many informal science clubs that emerged around this time in Britain, France and Italy: the power of print meant that, from its very inception, science was an international business that respected neither city walls nor national boundaries.

However, with a core membership that never exceeded 10 or 12 people, the Oxford group exerted a disproportionate influence on the course of scientific history: nurturing or inspiring some of the nation’s most talented scientists and engineers, and paving the way for Britain to become a scientific super power.

Special thanks to: Oxford DNB, In Our Time, Moralist, MHS

Insects aren't necessarily renowned for their maternal instincts but new research suggests that we may be unfairly maligning many of our six-legged friends.

Sofia Gripenberg from Oxford University's Department of Zoology, and colleagues from the Universities of York and Helsinki, have reviewed the evidence for 'bad' insect mothers and report their findings in the March issue of Ecology Letters.

I asked Sofia about genes, evolution and the fine line between selfish and selfless behaviour:

OxSciBlog: Why has it been suggested that insects are 'bad mothers'?

Sofia Gripenberg: In plant-feeding insects, 'good' and 'bad' mothers differ largely in terms of what food they pick for their offspring. Since those larvae will typically have to make do with the particular plants on which they were laid as eggs, their mother’s judgement may literally mean the difference between life and death. In some cases, that judgement has actually been found to be anything but sound, with larvae found on lousy plants.

OSB: How have people tried to explain this 'bad' behaviour?

SG: A 'bad' mother may still be doing the best she can. Sometimes the plants of highest quality may simply not be around when needed, and the female will then have to lay her eggs on what she can find. According to another idea, insects may simply be faced with 'information overload': if two plants differ in terms of too many traits, the insect may not know which trait to go for.

Also, even an insect mother may also have to think of herself. In some cases, mothers have been shown to put their own needs above those of their offspring. For example, by laying her eggs where she can get some food for her own, an insect mother may be prepared to knock off a bit of quality for her offspring.

Paradoxically, a female may sometimes increase the chances of passing on her genes to future generations by ignoring the well-being of individual offspring.

OSB: What does your study tell us about the choices of insect mothers?

SG: We basically revive the myth of the good insect mother. Where previous research has often focused on explaining the cases where mothers tend to err, our study shows good choices to be the rule, not the exception for insect mothers.

Importantly, what we have done is not to add one more study of one specific insect species, but to summarise work published to date. In this context, our results also reveal a little bit about why some mothers may be better than others. In particular, our study seems to support the idea about 'information overload', since insects choosing between a few different plant species actually seem to make more accurate choices than insects choosing between a wide assortment of plants.

OSB: How do these results contribute to our understanding of evolution?

SG: Our results suggests that 'good motherhood' is a result of fine-tuned natural selection. Where many previous studies have focused on factors preventing evolution towards good motherhood, our study shows that when you look at the combined evidence, these are still just blemishes on the bigger picture; that one still shows the picture of a beautiful insect mother!

OSB: What new avenues of research does your study suggest?

SG: When we started this study, we hoped to be able to say more about why insect mothers differ in terms of their judgement - about the factors causing some females to make worse choices than others. After now having read everything we have found on the topic, we have actually discovered that only a small fraction of articles are written in a way which allow straightforward comparisons of key results. This is something that we want to improve upon.

What we hope is that the database that we put together for our paper will continue to grow, and later allow for deeper synthesis of factors affecting optimal motherhood. By establishing this joint depository for all ecologists working in this field, we hope to get everybody to think more about how their own work can contribute as efficiently as possible towards the broader picture.

Dr Sofia Gripenberg is based at Oxford University's Department of Zoology

- ‹ previous

- 220 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?