Features

Technology originally developed to track badgers underground could soon be used to locate people in an emergency situation such as a bomb attack or earthquake.

GPS is good at pinpointing locations in open spaces but below the surface it's a different story. The limitations of conventional tracking technology were exposed in the 2005 London bombings, and numerous earthquakes since, where the emergency services struggled to locate people in underground areas or buried beneath debris.

Positioning indoors is also a challenge, with no clear winning technology that is able to address people's day-to-day needs, such as finding their way around an airport.

In 2009 Andrew Markham and Niki Trigoni, from Oxford University's Department of Computer Science, faced similar problems when they joined a project to study badgers in Oxford's Wytham Woods. The animals spend much of their lives underground where conventional technology couldn't keep tabs on them.

The solution developed by Andrew and Niki is a technology based on generating very low frequency fields. This has the unique advantage of penetrating obstacles, enabling positioning and communication even through thick layers of rock, soil and concrete.

'Most technologies are only checking the magnitude of the signal – the signal strength from each transmitter – to work out distance,' Andrew told Mark Piesing of Wired.co.uk. In contrast the new technology measures 'vectors, which give you the magnitude and direction… Our technology can work out your position in three dimensions from a single transmitter.' This contrasts with other approaches such as GPS or WiFi which are based on triangulation and typically require signals from at least four transmitters.

After the work with badgers the team realised the technology had potential applications in many areas such as location-based advertising, finding victims in emergencies, and tracking people and equipment in modern mines. They started working with Oxford University Innovation to commercialise their research and are currently raising money for a spinout firm, OneTriax, to be led by CEO Jean-Paul van de Ven, who has significant experience in mobile location based services.

The basic software has already been developed and the team believe that obstacles, such as the fact that low frequency fields vanish very quickly, can be overcome with clever signal-processing algorithms.

The aim is to incorporate the new technology into smart mobile devices: a demonstrator on an Android platform is being developed and, once the technology is perfected, versions suitable for popular smart phones, such as the iPhone, shouldn't be far behind.

Transit of venus

Transit of venusVenus is visible as the dark spot at the extreme right on the face of the Sun.

Andrew, from Oxford University's Department of Physics, told me:

‘The shots were taken with a normal digital SLR and a fairly long lens (70–200 mm plus a 1.7x teleconverter), but nothing more complex than that. You should of course never look at the Sun with the naked eye, especially through a camera or telescope, but on this occasion the thick clouds had a silver lining and protected me - and, as a bonus, made the shot a lot more atmospheric too!’

Even people at low risk of heart problems would benefit from statins, cheap drugs that lower levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol in the blood.

That’s the main finding of a giant collaborative study coordinated by Oxford’s Clinical Trial Service Unit and the Health Economics Research Centre, and published in The Lancet today.

About half of deaths from cardiovascular disease occur in people with no previous history of the disease, so preventing such deaths can only be done by targeting seemingly healthy people. The new research shows that treating healthy people who are for some reason at increased risk of disease would be effective, and safe, and it could see moves made toward offering these drugs to many millions of middle-aged people around the world, saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

‘The study settles once and for all previous uncertainties about whether people at low-risk of heart disease – healthy, middle-aged people – would see benefits from taking statins,’ says Professor Colin Baigent, who led the study. There would be fewer ‘events’ such as heart attacks and strokes, and this would greatly outweigh risks of any side-effects of the drugs.

The study used data for 175,000 individual participants taking part in 27 different randomised trials of statins that on average ran for around 5 years. Well over 50,000 of those people included in the analysis were at low risk of heart disease, with this group experiencing around 2000 heart attacks, strokes or similar.

With the potential of statins to save many lives, low risks of known side-effects, and the cheap cost of the pills (now that generic versions have become available over recent years), the question now switches to what should the guidelines be: how low should your risk of heart problems be before your doctor starts prescribing these pills?

Colin puts it like this: ‘To what extent should society spend resources on healthy people where there are small individual benefits but it offers the possibility of saving more lives across populations?

‘Should everyone get a statin? No. But where do you draw the line? GPs currently offer statins to people with a previous history of cardiovascular disease, and also to healthy people whose risk of such an event exceeds about 20% over 10 years. Our work suggests that we could save many more lives if we lowered that threshold, and we think that it would be sensible for NICE to review their recommendations in the UK to see whether they agree.’

Measures for preventing cardiovascular disease include encouraging healthy exercise, improving diet and stopping smoking, and all have their part to play in preventing these problems. But Colin emphasises that additional benefits are possible through wider use of statin therapy.

‘Now we have these enormously beneficial tablets that our research shows could play an even greater role in an effective public health strategy,’ says Colin.

Statins are not just for people with high cholesterol, but may be appropriate for anyone who is at increased risk. ‘The emphasis has been on treating according to people’s cholesterol levels,’ says Colin. ‘We need to get away from that focus on cholesterol levels in people’s blood and instead think about their level of risk of cardiovascular problems. Our research shows that if a person has an increased risk of heart attacks, perhaps because they are overweight or a smoker, and yet have normal cholesterol levels, then that person would benefit if their cholesterol was reduced to lower levels. It’s a different way of thinking about it, because we have been encouraged to know our ‘cholesterol level’, whereas what we really need to know is our ‘risk level’, and we should base our decisions about whether to commence statin treatment on that information and not solely on cholesterol levels.’

So what did the study published today in The Lancet do?

Colin explains: ‘We were interested in low-risk people and whether these very healthy people would still experience a benefit from taking statins. There had been controversy over whether there was a benefit of statins for those at low risk of heart attacks. Some studies suggested it didn’t exist, some did.

‘We used information recorded in the trials to set participants [all 175,000] in order of risk. We used measures like cholesterol level, blood pressure, whether or not someone was a smoker to calculate their risk of a heart attack or stroke. We worked out who had the lowest, who the highest and ordered them in line for every trial.’

The researchers then grouped everyone into brackets of risk of having a major cardiovascular event over the course of five years, from those who had <5% risk at one end to >30% risk at the other.

‘Because we had all the data on heart attacks and strokes from the trials we could check the risk scores accurately described what happened,’ Colin explains.

Those in the bottom risk groups do come predominantly from six or seven of the 27 randomised trials included in the analysis. But Colin says including all people from all the trials meant they didn’t just look at those trials that set out to look at low-risk healthy people, they looked at all the available data.

And the results across all risk groups were comparable: Those with low risk of heart events see similar proportional reductions in heart problems to those at much greater initial risk.

But those with a much bigger risk to begin with would see a larger drop in risk, so it’s important to look at the absolute figures.

The researchers estimate that for every 1000 largely healthy people (less than a 10% risk of heart problems over five years) lowering their ‘bad’ cholesterol levels by 1 mmol/litre through taking statins (a fair outcome of statin therapy, stay with me), there would be 11 fewer heart attacks or strokes over a 5 year period. That’s perhaps hard to work through what those numbers mean. It’s perhaps not a huge change for each individual.

But would add up to many heart attacks, strokes, and deaths prevented in healthy people if lots of people were taking the pills.

A better way of looking at these numbers is probably visually. A figure at the end of the Lancet paper makes clear the number of heart attacks and strokes avoided through taking statins. There are many more heart events prevented in the high risk groups, of course. But the benefits do extend right the way to the bottom, with measurable bars still appearing for the much larger population of people at very low risk of heart problems only lowering their bad cholesterol by a bit.

In taking any drug there is the potential for side-effects, and when so many people are taking statins, these are important to consider even if they occur at low rates.

There are a number of known side-effects of statins but these are uncommon and the beneficial effects in terms of preventing heart attacks and strokes greatly exceed the small risks, even among those at very low risk. ‘These are very safe drugs,’ emphasises Colin.

Statins can cause muscle problems, and problems in the liver – though these reverse on stopping taking the pills. Recently, statins have been linked with an increased risk of bleeding in the brain. These are rare, unusual but real side-effects, the evidence shows. Statins may also increase the risk of developing diabetes, but the cardiovascular benefits of statins in low-risk people are substantial even after allowing for this increase in diabetes.

That’s very reassuring when hearing stories of people experiencing muscle pain after starting statins. Some of these may not be connected to the statin and may have happened anyway. But without evidence like this it is certainly harder to compare these tales of side-effects against the heart attacks that didn’t happen, where there is no tale to be told.

The study received public and charity funding from the British Heart Foundation, the UK Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK and others. The trials included in the analysis were mostly supported by research grants from the pharmaceutical industry.

For millennia birds have been prized, even hunted, for their beautiful plumage but what makes their feathers so colourful?

A new X-ray analysis of the structure of feathers from 230 bird species, led by Vinod Saranathan of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, has revealed the nanostructures behind certain colours of feather, structures that could inspire new photonic devices.

A report of the research appears in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

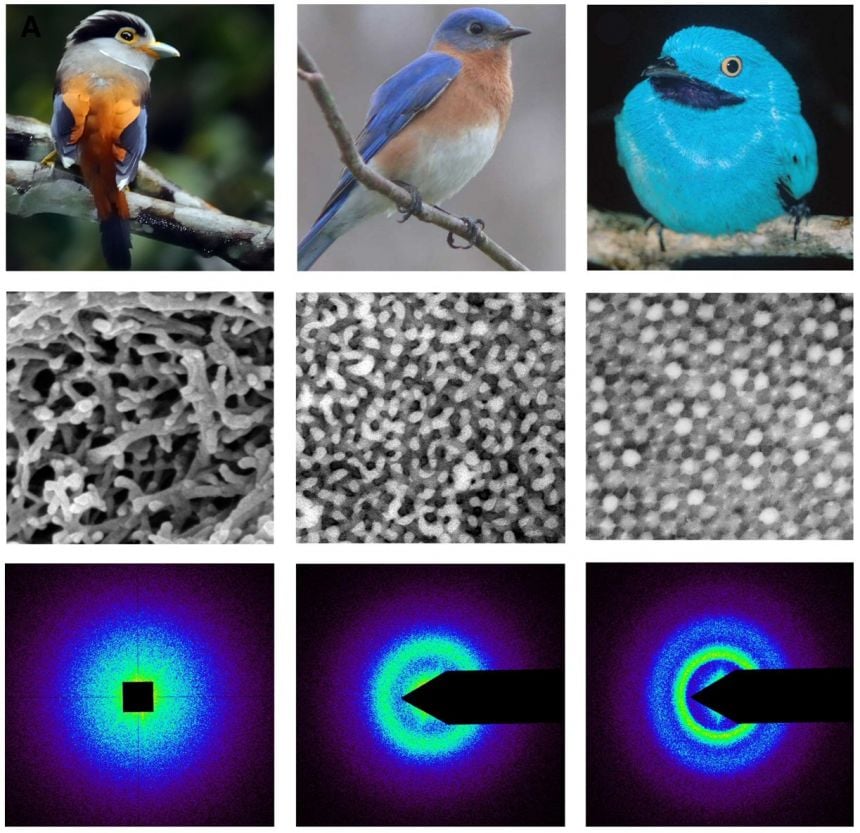

Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds

Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds ‘Pigments or dyes are the most common ways to make colour in birds as in other organisms. Pigment molecules absorb certain portions of the white light spectrum and the portions that are not absorbed manifest as the colour we see,’ Vinod tells me.

‘For instance, melanosomes, granules filled with the pigment melanin, produce blacks, browns and reddish-browns in feathers, whereas other pigments such as carotenoids produce the majority of bright yellow, orange or reddish colours.’

He explains that parrots even have their own class of pigments (psittacofulvins) which give them their vivid yellow and red plumage.

‘However, there are no known blue pigments found in vertebrates and the only known green pigment in birds is found in turacos, a group of birds endemic to sub-Saharan Africa,’ Vinod says.

‘Birds have evolved to produce shorter and middle wavelength colours such as violet, indigo, blue and green structurally instead by the scattering of light photons by nanoscale sub-surface features in the feathers that are called biological photonic or biophotonic nanostructures.’

It was these ‘structural’ (as opposed to ‘pigmentary’) colours that Vinod and colleagues from the US set out to investigate.

Vinod explains: ‘These features are basically repeating variation in material composition on the order of a few hundred nanometres, which matches the wavelengths of visible light.

‘In bird feather barbs (barbs and barbules are respectively the primary and secondary branches of a feather), the complex nanostructures, made up of the protein beta-keratin and air, occur in one of two fundamental forms - either as a tortuous network of air channels in keratin (like a porous sponge) or as an array of spherical air bubbles in keratin (like Swiss cheese), but sometimes as more disordered and highly variable versions of these two forms.’

Despite this apparently chaotic arrangement the team’s X-ray scattering experiments found a kind of order (known as ‘quasi-order’) in the variation and sameness of feather structures that accounts for their unusual optical qualities.

Because the quasiordered architecture of barbs interacts strongly with light, often producing double peaks, pure green or red colours cannot be produced structurally. But, Vinod tell me, many birds have evolved a way round this:

‘Some birds such as the tanagers found in the Neotropics, have combined an orange or red pigment with a spongy barb nanostructure tuned to reflect in orange or red wavelengths in order to make bright and saturated colours, which cannot be produced using either biophotonic nanostructures or pigments alone.’

Not only have very similar barb structures evolved independently in many families of birds (at least 44) but these look very much like other nanostructures seen in the physical world, such as beer foam, corroding metal alloys, and oil-in-water. It suggests that, like these latter structures, feather nanostructures may have evolved by a process of self-assembly (the phase separation of keratin from the cytoplasm of the spongy barb cells).

‘This suggests that many lineages of birds have independently evolved to utilise the self-assembling properties of a polymerising protein in solution to create optical nanostructures,’ Vinod comments.

The findings feed into his current work with Ben Sheldon studying the ultraviolet light reflecting crown structural colour ornaments of blue tits, which males use to attract females and see off rival males:

‘By studying these non-iridescent barb structural colours across all birds, we have a better idea of the distribution of these colours across the evolutionary history of birds so that we can trace the evolution of barb structural colours in other birds closely related to the blue tits.

‘That these barb nanostructures could be self-assembled intracelllularly from beta-keratin, the most basic constituent of feathers, suggests that there may be little or no cost involved in producing such structural colours.’

Yet the secrets of structural colours aren’t just for the birds, they could also help to develop new materials for photonic devices that would not allow the passage of a certain band of wavelengths in any direction: such materials are currently hard to fabricate defect-free and on an industrial scale.

Vinod comments: ‘The nanostructures in bird feather barbs, that are likely self-assembled and have evolved over millions of years of selection for a consistent optical function, could be used to inspire novel photonic devices.

‘They could be used as biotemplates for the fabrication of photonic materials using better technological raw materials (such as titania or silica), or we can try and mimic their process of self-assembly using synthetic polymers for colour tuneable applications.’

So, in the not too distant future, we could be growing our own artificial feathers not just to dazzle and amaze but to harness the power of light.

A report of the research, 'Structure and optical function of amorphous photonic nanostructures from avian feather barbs: a comparative small angle X-ray scattering analysis of 230 bird species', is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Image: Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds and the underlying nanoscale morphology of the colour-producing (photonic) nanostructures revealed using electron microscopy and synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Credits: Collage by Vinod Saranathan, photograph of Plum-throated Cotinga (Cotinga maynana) by Thomas Valqui.

A new examination of silkworm cocoons suggests how they could inspire lightweight armour and environmentally-friendly car panels.

Scientists from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology studied 25 types of cocoons for clues to how the structures manage to be very tough but also light and able to ‘breathe’.

Fujia Chen, David Porter, and Fritz Vollrath report in Journal of the Royal Society Interface on their research into the factors that enable cocoons to protect their occupants.

‘Cocoons protect silkworms in the wild as firstly a hard shell, secondly a microbe filter and thirdly as a climate chamber,’ Fritz tells me, adding that this order of importance will change depending on the threats and environmental conditions faced by each species.

The lightness of cocoons is down to both the material they are made of – silk – and the way that this is turned into a layered composite material with a clever arrangement of silk loops that are woven together with gum only at the intersections.

‘By controlling the density of the 'weave' the animal controls the material properties of each layer, and by having different properties for different layers the animal can make tough yet light structures,’ Fritz explains.

‘In addition many wild silk worms integrate mineral crystals (which they obtain from their food plants) into the composite to give extra strength. Silk cocoons could bring inspiration to light-weight armour by showing ways that animals have solved some of the problems faced by human designers.’

At present most of the cocoons produced around the world are boiled and unravelled to be made into textiles, but the researcher suggest that they could be used to create composite materials that could satisfy the demand for car panels and other components in fast-growing economies such as India and China.

‘Silk cocoons are fully sustainable, non-perishable and climate-smart agricultural products,’ Fritz comments. ‘They are also very light, tough composites. Using cocoons as base materials, in combination with equally sustainable fillers should help us make sustainable composites with many layers of complexity.’

The next stage in the research will involve looking for natural glues and resins that interact well with mats of ‘raw’ (unwoven) cocoons.

Fritz adds: ‘This will require a good understanding not only of the cocoon materials but also of composite theory and the issues involved in turning that into practice.’

- ‹ previous

- 188 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?