Features

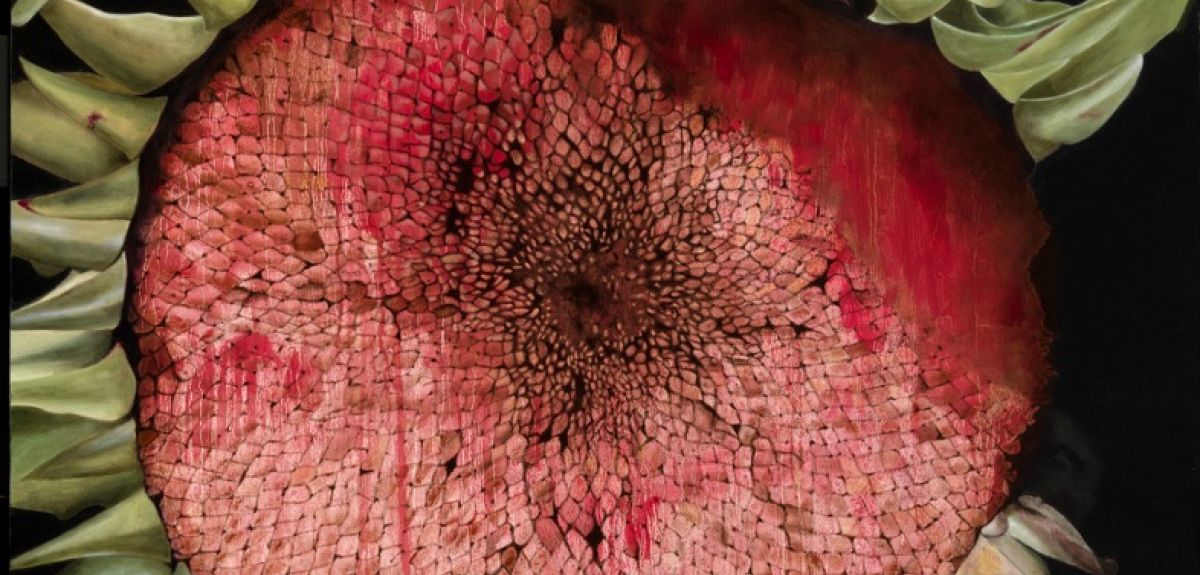

Artist Patrice Moor has spent the last 18 months as artist in residence at the University of Oxford Botanic Garden. 'Nature Morte', an exhibition based on her time at the Garden, opens on Saturday 7 March.

'My subject is not morbid – there is an emphasis towards life holding death in mind and the cycle of life,' says Patrice.

'Gardens lend themselves well to this and I felt hugely privileged to be able to observe and spend time at the Oxford Botanic Garden. Each season is full of interesting changes, as an artist all things can be a source of inspiration.

When Peter Medawar began his research career at Oxford University in 1935, he remarked that he was '(allocated) a room much too good for a beginner'.

This generous gesture from Professor Howard Florey who allocated the room turned out to be far-sighted: while at Oxford, Peter Medawar made the first discoveries that ultimately led to him winning the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1960. His eventual discovery of how the body can learn to accept tissues from another donor opened the door to successful organ transplantation

He was also a well-known science communicator in his day, giving the 1959 BBC Reith lecture and writing numerous books and articles for a general reader. Richard Dawkins has called him 'the wittiest of all science writers.'

2015 marks the centenary of his birth, which has just been celebrated with a special lecture series at the Department of Zoology, where he was an undergraduate.

Beginning research

Peter Medawar completed a first class honours degree in Zoology at Oxford in 1935, after which he was awarded the Christopher Welch scholarship and the senior demy of Magdalen.

But the Zoology department did not have the equipment for the tissue culture work which became the focus of Medawar’s DPhil, so he was dispatched down South Parks road to the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology. The School was the site of a new state of the art lab – and a new Professor of Pathology, Howard Florey.

Howard Florey himself won the 1945 Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine for his role in the making of Penicillin, the new 'wonder drug' whose effects were nothing short of miraculous at the time.

The research team that Florey recruited – including the young Peter Medawar – ushered in the modern age of antibiotics.

While Medawar was mostly working on tissue cultures at this point, he also contributed experimental results to the famous second 'Penicillin paper' which established Penicillin’s effects in a living organism, even though he is not credited as an author.

The hard graft

Medawar continued working in Oxford as the second world war began, dramatically changing the direction of his research.

During the Battle of Britain, the now-married Peter Medawar and his wife heard an aeroplane flying low over their Oxford garden, followed by an almighty crash. Oxford was spared the bombing that affected many other cities, and the sound they heard was not a bomb but the crash landing of a British plane.

The plane pilot was badly burnt, and his doctors asked if Medawar's experience with tissue culture could help in treating him in any way. Medawar was also challenged by a colleague who had a clinical interest in the treatment of severe burns to see if he could grow skin in tissue cultures.

Responding to this challenge, Medawar travelled up to Glasgow (where he later claimed that his diet consisted of 'allotropes of porridge'), and worked on transplanting patches of skin from donors to burn patients.

He found that a second set of transplants was rejected much faster than the first, a finding that highlighted the role of the immune system in the rejection of donor tissue.

Back in Oxford, Medawar continued his work on dissecting how the immune system reacted to tissue grafts from another donor, eventually leading to their rejection.

By the time he left Oxford in 1947, Peter Medawar’s research had already established that the body rejected tissue grafts from a genetically unrelated individual through an immune mechanism, and that this mechanism was not mediated by conventional antibodies.

Medawar continued his research at the University of Birmingham and at University College London, writing the seminal Nature paper which described how to make normally-rejected donor tissue grafts immunologically acceptable to the body.

This discovery paved the way for organ transplants. For his role in this work, Peter Medawar was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1960.

Later life

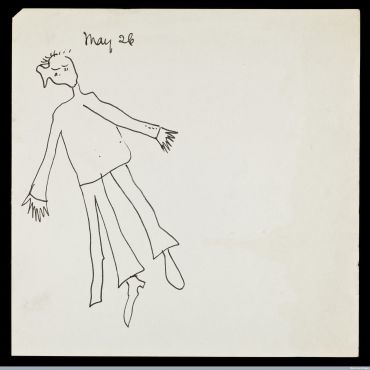

Peter Medawar was struck down by a stroke while delivering a speech in Exeter Cathedral in 1969, but he continued to write through the multiple strokes he suffered until his death in 1987. He made the self-portrait below while recovering in a respite home in 1970.

The Peter Medawar Building for Pathogen Research at Oxford University was named in honour of his contributions to scientific research.

'Peter Medawar was an absolutely brilliant teacher,' according to one of his former students, Dr Henry Bennet-Clark, Emeritus Reader at the Department of Zoology. 'He not only made sure that we knew the facts, but he also provoked our interest in science.'

Dear wife and bairns

Off to France – love to you all

Daddy

On first reading, this note from George Cavan to his wife Jean and three daughters does not appear out of the ordinary.

But it was the last message he ever wrote to his family, two weeks before being killed in action on 13 April 1918 at the Battle of Hazelbrouck in France. The note only reached his family thanks to the goodwill of a passer-by.

George's granddaughter, Maureen Rogers, picks up the story. 'At the end of March 1918 George was away at training camp the orders came through to dispatch to France,' she explains.

'The train he was on with his troops went through his home station (Carluke in Scotland) but did not stop there. He threw out onto the station platform a matchbox containing a note to his family.

'On one side was the name of his wife and on the other the message to the family.'

The note came to light when Maureen submitted it to Oxford University's Great War Archive, which has collected and digitized more than 6,500 items relating to the First World War that were submitted by the general public.

The Archive was set up by Dr Stuart Lee of Oxford’s English Faculty and Academic IT Services and was used as the model for the Europe-wide Europeana 1914-1918 project..

Maureen lives in Australia and the subsequent blog post on the Great War Archive website triggered an unexpected set of events.

'We received a comment from George's family in Scotland who were unaware of the matchbox story,' says Alun Edwards, a project manager of the Great War Archive.

'Through this the family branches were able to join together their elements of their ancestors' stories. This formed the basis for a chapter of a book, published by the British Library, called "Hidden Stories of the First World War" by Jackie Storer.'

IT Services' work at the forefront of community collections will be presented at the forthcoming 19th annual Museums and the Web conference in April 2015 in Chicago.

Lizards originally from balmy southern Europe have adapted to the colder English climate within a few decades, a study from Oxford University has found.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, found that wall lizards (Podarcis muralis) in England had eggs that developed faster, compared to the same species in France and Italy.

As reported on BBC online, this adaptation to a cooler climate is likely to have helped this new species to gain a foothold in England.

I caught up with Dr Tobias Uller at the Department of Zoology and asked him about his work.

OxSciBlog: What was new about your study?

Tobias Uller: We show that adaptation to a cooler climate can happen very quickly, over just a few decades.

By combining our measurements of soil temperature variation, computational modelling, and carefully controlled lab experiments, we show that there is natural selection for a shorter incubation period in wall lizard eggs in England. This selection is caused by the colder temperature of the soil in which the lizards lay their eggs.

Wall lizards have adapted to this selection pressure by laying eggs which are further along in their embryonic development.

We also found that once laid, the eggs develop much faster.

The net effect is that wall lizard eggs in the UK hatch quicker than they would when they were first introduced into England some decades ago.

Wall lizards

Wall lizardsImage courtesy of Geoffrey While

OSB: How common are wall lizards in the UK?

TU: There are about 30 populations of these lizards in the UK. They turn up as far north at the Gower Peninsula (in Wales), and current populations were introduced to this country less than 100 years back.

Some of these populations were deliberately introduced. (This practice is now illegal).

But these lizards are also quite commonly kept as pets, so some populations have been established by ‘escapees’, from animals brought in as pets.

Our research was based on populations in Dorset and the Isle of Wight. These were separate introductions. So the fact that the pattern of changes is the same in both populations gave us more confidence that this is no coincidence.

OSB: What did you do with the female lizards that you collected from these areas?

TU: We kept and raised animals collected from different areas in the same laboratory conditions.

This is important, because if females in Italy and in England lay their eggs at different stages in embryonic development, this may be because of the different temperatures they are exposed to in the wild. By keeping animals from different geographic locations under the same conditions, we can say that any differences that we find are due to genetic differences between the population, rather than differences in the environmental conditions they are exposed to.

Under these controlled conditions, we checked what embryonic stage the eggs were at when they were laid.

We then incubated the eggs laid by different populations at many different temperatures, to see how long they took to hatch.

We used this data to generate developmental rates for different populations, and we could then compare the developmental rate for 'native' (from Italy and France) and 'introduced' (from England) populations.

OSB: What did you find?

TU: There are two different ways that lizards in England could adapt to colder soil temperatures in their nests.

Lizards can 'bask', i.e., they can maintain a higher body temperature than their surroundings. So female lizards can lay their eggs later, when the embryos are more advanced. This reduces the overall time the eggs have to spend in the cold soil.

The other strategy is for embryos to increase the rate of development, which also reduces the time the eggs spend in the cold soil.

We found that the lizards in England have evolved by making use of both these strategies.

The net result is that wall lizard eggs in England hatch about two weeks earlier now than they would have done when the species was first introduced.

OSB: Do these results have implications for climate change?

TU: We show that the adaptation to changes in temperature can be very rapid, a matter of decades.

Evolutionary biologists increasingly expect to see more examples of this kind of rapid adaptation to a changing climate.

Sexual reproduction produces new combinations of genes, a process that is thought to prevent the accumulation of harmful mutations. A study in Nature Genetics now provides the first experimental evidence that recombining genes stops harmful mutations from piling up in humans.

I talked to the lead researcher, Dr Julie Hussin at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, about the evolutionary biology of sex.

OxSciBlog: Why is the evolution of sexual reproduction still a bit of a puzzle for researchers?

Julie Hussin: Well, because asexual reproduction just makes more sense!

If an organism has got to the stage where it can reproduce, its genes are clearly sufficiently adapted to the environment that it can survive.

From this point of view, it doesn't make sense why you'd risk mixing your genes to make a new, unproven genome, when the genome you already have has been proven to be good enough to survive.

OSB: So what advantage might sexual reproduction offer to a biological organism?

JH: Many decades of theoretical work show that when genes are not mixed together to make new combinations, over many rounds of reproduction mutations which are only slightly harmful slowly begin to accumulate in the organism's genome.

Over time, this can potentially drive the species to extinction.

Sexual reproduction is one way of ensuring that recombination happens each time the organism reproduces, preventing the accumulation of genetic defects.

OSB: You've mentioned that this rationale for sexual reproduction is supported by theoretical work: is there previous experimental evidence supporting it?

JH: Experimental evidence is much thinner, and there has been none in humans.

The problem with demonstrating that human recombinations have an effect on genetic mutations is that they affect mutations that are very rare in the population. The impact of recombination on the accumulation of these mutations is thus detectable within whole populations, rather than in single individuals.

So to find them, we not only needed very large sample sizes, but also data across the whole genome.

It is only recently that we have had the technology to get large-scale genomic data from many, many people: we used high-coverage gene sequencing data from over 1,400 people, collected by the 1000 Genomes and the CARTaGENE projects.

Using this data, we have shown for the first time that recombination rates have an effect on the accumulation of harmful mutations in humans.

OSB: How did you use this data?

JH: The rate of recombination is actually not uniform across the human genome, and rates vary quite dramatically across genomic regions.

So we compared how many mutations had accumulated in regions of the genome where there is a lot of recombination ('hotspots'), versus regions where the recombination rates are low ('coldspots').

Our thinking was that if recombination discourages the accumulation of harmful genetic mutations, then there will be a difference in the proportion of harmful mutations there are in the 'hotspots' versus the 'coldspots'.

OSB: What did you find?

JH: Exactly that: genome regions where the recombination rates are low had many more harmful and disease-associated mutations, compared to genomic regions with high rates of recombination.

What was a surprise was that the genes in the coldspot regions were more likely to be involved in really essential processes, such as DNA repair and cell maintenance. Mutations here were particularly likely to affect the health of people carrying the mutation.

OSB: Why are genes for essential functions located in regions where it turns out that there is greater chance of a harmful genetic mutation?

JH: We don't know.

But it is possible that there is a greater cost for a 'bad recombination event for these genes.

Very occasionally, recombining genes can result in a deleterious variation. When this happens for a very essential gene, the cell simply dies.

From an evolutionarily perspective, genes for essential cellular functions are very old: they evolved millions of years ago, and they've been handed down to many organisms because they clearly work.

So it makes sense not to 'mess' too much with them, and this could be why they're in coldspot genome region.

In contrast, genes in charge of the immune system and immune responses are mainly found in hotspots.

These are relatively new functions: perhaps the new variants that gene recombinations yield are still required here, to better adapt to the environment.

OSB: Did you also find genetic differences between the different human populations you looked at?

JH: Yes!

In older, larger populations, we found a much smaller difference in harmful mutation accumulation in the coldspots versus the hotspots.

For example, we had data from the French-Canadian population, which was established only 400 years ago. It started with only 8,000 'founders', and it is still quite small.

In contrast, as Africa is the birthplace of modern humans, the African populations we looked at have a larger effective population size, which means more people have contributed to the genetic diversity.

Although there is little evidence for a difference in the number of harmful mutations between human populations over the whole genome, the French-Canadian population had a larger proportion of harmful mutations in their genomic coldspots.

Many of these mutations were specific to the French-Canadian population: they were either rare variants which happened to be there in some of the 8,000 population founders, or they have originated for the first time since the founding of Quebec 400 years ago.

We found similar results for the Finnish and Tuscan Italian population we looked at.

So we think that the population history of a group of people can also have an effect on the pattern of harmful genetic variants.

OSB: Where is your research headed for the future?

JH: In this study, we ignored the X and Y sex chromosomes.

We know that the Y chromosome never recombines, and the X recombines only in females, so the patterns there are likely different and deserve further investigation.

We would also like to test the same theory in other mammals. The availability of recombination maps and large-scale population data in other primate species, for example, makes this possible in the near future.

- ‹ previous

- 153 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?