Features

What did ancient words spoken in Europe and Asia over 6,000 years ago sound like?

A project at Oxford University is using scientific methods to answer this question.

'Since the 19th century, historical linguists have tackled this question by studying the forms of words in many languages at different points in history, using that knowledge to infer the forms of words from a time before writing,' says Professor John Coleman, Principal Investigator of the Ancient Sounds project, which is based in the Phonetics Laboratory, part of Oxford's Faculty of Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics.

'We are taking a revolutionary new approach, which combines acoustic phonetics, statistics and comparative philology.

'Rather than reconstructing written forms of ancient words, we are developing methods to triangulate backwards from contemporary audio recordings of simple words in modern Indo-European languages to regenerate audible spoken forms from earlier points in the evolutionary tree.'

In 2013 the project reconstructed the pronunciation of spoken Latin words for numbers. This year Professor Coleman has a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) to extend this work to Germanic languages like English, German dialects and Dutch, as well as Modern Greek.

For example, the English word 'three' comes from Proto-Indo-European word 'treyes', a word rather like the Spanish 'tres'. This sound file shows the possible linguistic development of the word.

The English 'two' comes from Proto-Indo-European 'dwoh', as illustrated in this sound file.

The project is also investigating questions like: How far back in time can extrapolation from contemporary recordings progress? How “wide” and diverse must a language family tree be in order to triangulate to sounds that are plausible i.e. reasonably consistent with written forms from antiquity? Do sound changes proceed at a uniform, gradual rate?

Professor Coleman spoke about his project yesterday (7 September) at the British Science Festival in Bradford and will present at the Oxford University Alumni Weekend later in the month.

Readers can follow the project’s updates on the Ancient Sounds website and Twitter feed.

Ancient Sounds is run in collaboration with the Statistical Laboratory at the University of Cambridge.

From deadly pandemic to asteroid strike, most of us can name a few ways the world might end. The end of the world as we know it fuels Hollywood plots and bestsellers. But is this a modern phenomenon?

Dr Daron Burrows, of the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, has launched a new project, The Apocalypse in Oxford, to digitise a collection of medieval texts which suggest the apocalypse has been in fashion for much longer than you might think.

'There was something of a vogue for illustrated manuscripts of the Revelation – the Biblical Apocalypse - in the 13th century,' says Dr Burrows. 'There were at least 80 produced between the 13th and 15th centuries, of which around half originated in Britain.'

The Bodleian Library currently holds five different Anglo-Norman copies of the French Prose Apocalypse, vividly illustrated with beasts, angels and other scenes from the Book of Revelation. Dr Burrows will scan and transcribe the books, which will then be made available to the public online.

'There are two main factors in the popularity of these books,' said Dr Burrows. 'In the 12th century, Joachim of Fiore, a Calabrian abbot, wrote a gloss on the Book of Revelation which seemed to indicate that the world would end in 1260, and later commentators thought the Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe confirmed his interpretation. This may have sparked some popular interest in the Apocalypse.

'But perhaps the more significant factor is that these books were very expensive luxury items. As far as we know about their provenance, the majority were commissioned and owned by noble families rather than, for example, religious institutions. These families may well have owned an Apocalypse manuscript less for its moral or spiritual lessons than to manifest their wealth and prestige.'

Despite their origins in the British Isles, the five books which Dr Burrows will digitise are written in French. They include a translation of the Book of Revelation, and a commentary whose origins are not yet clear.

'After the Norman Conquest, French became the language of power and authority in Britain,' said Dr Burrows. 'All administration was carried out in French, the English aristocracy quickly began to use it, and it became the language of literature.

'Perhaps paradoxically, French was used less frequently in material written in France itself during this period: indeed, two-thirds of all surviving 12th-century manuscripts of French literature originated in Britain.'

The form of French which was used in the British Isles was mainly influenced by the Norman dialect which William the Conqueror brought with him, but Anglo-Norman also features traits from the other regions from which the Conqueror's troops were drawn.

It was also modified by the accents of British speakers. However, it can be difficult for philologists to distinguish between different dialects in written text, because spelling was not standardised.

'When texts are written in verse, the rhymes can often provide clues regarding the dialect in which the poem was originally written,' said Dr Burrows. 'Since there was no standardised orthography, scribes copying a text would commonly change spellings to match their own regional conventions.

'Changing the sounds at the rhyme, however, would require more drastic changes, and so rhymes often preserve the phonology of the original text.'

For example, in medieval Continental French, as in modern French, it would be impossible to rhyme nul and seul, but in Anglo-Norman, the assimilation of sounds makes this a common rhyme.

Such comparisons allow philologists to state with some certainty whether a text originates from France or from Britain. However, the five Apocalypses in the Bodleian are all in prose. As part of the project, Dr Burrows will analyse the texts in detail, aiming to shed light on their provenance.

A traditional method of farming often praised for being environmentally sustainable actually releases 'significant' greenhouse gas emissions, an Oxford University study has found.

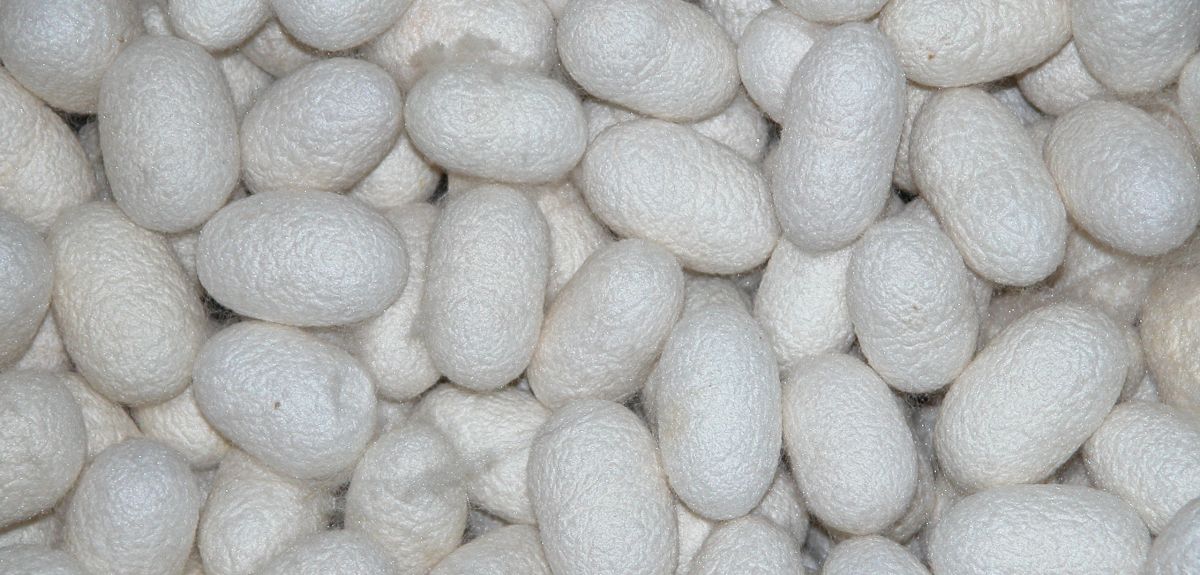

Integrated fish farming is common in aquaculture and a particular system from southern China combining silk production and aquaculture has been regarded as a prime example of multi-functional agriculture with a 'closed-loop' recycling process.

Organic residues from silk production are added to ponds to encourage the growth of phytoplankton, feeding fish. Waste accumulated in the pond sediments is removed and used to fertilise mulberry, which is in turn fed to silkworms.

A team led by Professor Fritz Vollrath of the Oxford Silk Group analysed the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions. Their results are to be published in the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment.

'We have found that the formation of methane in pond sediments can be a significant source of emissions blamed for global warming,' said Professor Vollrath.

'Until now this method of small-scale farming has been held up as a shining example of environmentally-friendly farming. But our results suggest it may make an appreciable and previously underestimated contribution to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.'

He added: 'The effect is significant because carp are the most heavily farmed fish in the world, and commonly raised in fertilised ponds.'

The Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology is an international centre of excellence for researching inflammation in the body, from causes to treatments. Professor Irina Udalova is the Institute's principal investigator of the genomics of inflammation. Her latest research has found that a protein known as Interferon Lambda Two (IFN-λ2) could restrict the development of debilitating inflammation, like that found in rheumatoid arthritis.

I spoke to her about the research and what it might mean for people with rheumatic diseases.

OxSciBlog: What are interferons and what do they do?

Irina Udalova: Interferons (IFNs) are a group within the large class of proteins known as cytokines, which are used by the immune system for communication between cells, in particular during microbial infection. They are probably most famous for their ability to interfere with viruses and protect cells from viral infection, but they have other immune functions as well.

OSB: Your latest paper looks at a protein called Interferon Lambda Two (IFN- λ2). What prompted you to look at this particular protein?

IU: We have been interested in the IFN-lambda system and in particular its possible role in inflammation since its original discovery in 2003. Our first venture in to the field was about IFN-lambda gene regulation and production. In 2009 we published a paper describing how the expression of the IFN-lambda 1 gene is regulated in human dendritic cells, which are the main producers of it.

Cytokines are proteins released by cells in response to environmental challenges to communicate with other cells. Interferon lambda is part of the type II cytokine family, which include other interferons, such as IFN-alpha, beta and gamma, but also interleukin 10 (IL-10), a cytokine famous for its anti-inflammatory effects. Interferon lambda has structural similarities to both IFN-alpha and beta and IL-10.

We have always hypothesized that being related to IL-10, IFN-lambdas may also have anti-inflammatory activity However, progress was hampered by the lack of good antibodies to the receptor and some uncertainty in the field as to what immune cells actually respond to IFN-lambda, making it difficult to detect.

OSB: How did you investigate the effects of IFN- λ2?

IU: We teamed up with the researchers at a firm called Zymogenetics who provided us with mice lacking IFN-lambda receptors – their cells could not be affected by IFN-lambda. The company also supplied recombinant IFN-lambda protein.

We used collagen to induce arthritis in the mice. Known as collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), this is considered to be a gold standard animal model of human rheumatoid arthritis. We either treated the mice with recombinant IFN-lambda at the first sign of arthritis or we left them untreated.

OSB: What were the results?

IU: To our great surprise, the first experiment with IFN-lambda treatment showed a complete reversal: The arthritis was halted and the joints of treated mice remained intact while the untreated mice developed severe inflammation, cartilage destruction and bone erosion.

We did many more experiments figuring out the right doses of the treatments as well as trying to understand how this protection works at the molecular level. It took us a couple of years of going through various possible cell types to find out that the main immune cells targeted by IFN-lambda were neutrophils.

OSB: What are neutrophils?

IU: Neutrophils are the cells in the very beginning of the inflammatory cascade. They recognise tissue injury or pathogens and begin digesting and destroying the invading microbes. They also send signals to other cells of the immune signal to come aboard, thus leading to a cascade of further immune reactions.

The role of neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases have been somewhat understudied as they are believed to have a very short life span. However, recent evidence suggest that they may live for much longer if activated and they contribute to shaping the immune response and associated effects on the body. In some other models of experimental arthritis, removing neutrophils prevents the disease.

IFN-lambda seems to prevent neutrophils moving to the site of inflammation, without significantly affecting their numbers in the blood. This is important, as it indicates the lack of toxicity and adverse effects.

OSB: What’s next?

IU: We do not know the exact molecular mechanisms behind these events. We plan to investigate those as well as examine other known properties of neutrophils and how treatment with IFN-lambda affects those.

Our immediate focus is on rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases where neutrophils play a part in disease development, such as vasculitis or gout.

Also most of our work has so far been done in a model system. We would like to validate the findings in human neutrophils and explore the possibility of re-purposing IFN-lambda (which is now in clinical trials for hepatitis C treatment) for inflammatory diseases.

Four times a year, OUP's free online dictionary OxfordDictionaries.com updates its list of words.

In the latest list of additions, announced today, there are a number of words used mainly by young people, often referring to food, drink and technology.

'New words, senses, and phrases are added to OxfordDictionaries.com when we have gathered enough independent evidence from a wide range of sources to be sure that they have widespread currency in the English language,' said Angus Stevenson of Oxford Dictionaries.

'This quarter's update shows that contemporary culture continues to have an undeniable and fascinating impact on the language.'

In a guest post, Kirsty Doole from Oxford Dictionaries takes us through some of the new entries:

'Today Oxford University Press announces the latest quarterly update to OxfordDictionaries.com, its free online dictionary of current English. Words from a wide variety of topics are included in this update, so whatever your field of interest, everyone should find something they think is awesomesauce.

Food and drink have provided a rich seam of new words this quarter, so if you’re feeling a bit hangry then pull up a chair in your local cat cafe or fast-casual restaurant and read on (but if you’re in the mood for something sweet then make sure they won’t charge you cakeage). Why not try some barbacoa or freekeh? As for something to drink, if it’s not yet wine o’clock, then you could dissolve some matcha in hot water to make tea.

The linguistic influence of current events can be seen in a number of this update’s new entries, from Grexit and Brexit to swatting. We also see the addition of deradicalization, microaggression, and social justice warrior.

Technology and popular culture remain strong influences on language, and are reflected in new entries including rage quit, Redditor and subreddit, spear phishing, blockchain, and manic pixie dream girl.

How we consume information is exemplified by additions such as glanceable, skippable, and snackable. This quarter also sees the addition of the words mecha, pwnage, and kayfabe.

Other informal or slang terms added today include NBD (an abbreviation of ‘no big deal’), mkay, weak sauce, brain fart, and bruh. Several modern irritations take their place in OxfordDictionaries.com today: who can fail to be annoyed by manspreading, pocket dialling (or butt dialling), or those instances where you MacGyver something and it doesn’t quite work. Never mind, ignore the randos, and go home and cuddle up with your fur baby.

Don’t get butthurt about our bants! Research by the Oxford Dictionaries team has shown that all of the words, senses, and phrases added to OxfordDictionaries.com today have been absorbed into our language, hence their inclusion in this quarterly update. Mic drop.

The full meanings of these words, and the other additions, can be found at OxfordDictionaries.com.

- ‹ previous

- 145 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?